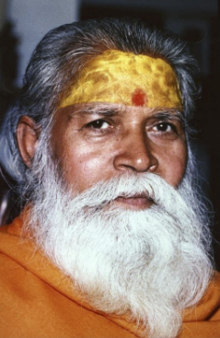

Swami Shantanand Saraswati (1913–1997) was Shankaracharya of the Jyotir Math monastery from 1953 to 1980; he was a direct disciple of Brahmananda Saraswati and succeeded him as Shankaracharya.

Swami Shantanand Saraswati | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Shankaracharya of Jyotir Math |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Ram Ji 16 July 1913 Achhati village in Basti district |

| Died | 7 December 1997 |

| Honors | Sankaracarya of Jyotir Math |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Philosophy | Advaita Vedanta |

| Ordination | 12 June 1853 |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Brahmananda Saraswati, Udiya Baba |

| Predecessor | Brahmananda Saraswati |

| Successor | Vishnudevanand Saraswati |

Disciples

| |

His life

editIn 1953, five months before his death, Brahmananda Saraswati, the Shankaracharya of Jyotir Math, made a hand-written will naming his disciple, Swami Shantanand Saraswati, as his successor.[1][2][3] Shantanand assumed the Shankarcharya-ship but his authority was later disputed by several of Brahmananda's disciples and followers who did not feel (due at least in part to Shantananda's lack of lifelong celibacy) that Shantanand met the requirements described in the Mahanusasana texts.[2]

Shantananda Saraswati became a devotee of Brahmananda Saraswati at an early age. He wanted to become a monk but Brahmananda Saraswati instructed him to marry. Due to this Shantanand lived the life of a householder, worked as a bookbinder, and supported a wife and child for fourteen years. Upon his wife's death he once more sought, and was granted, permission from Brahmananda Saraswati to become a monk. Shantananda was the first Shankaracharya to have lived as a householder for part of his life. This break in tradition has continued to cause controversy and dissent among some disciples of Brahmananda.[3]

Shantananda Saraswati received Western visitors from a number of organisations thus making his teaching available to many around the world.[4] In 1960 Dr Francis Roles (the named successor of P. D. Ouspensky) of The Study Society, travelled to India and became a follower of Swami Shantananda Saraswati; a few years later Leon MacLaren of the School of Economic Science also visited Shantananda Saraswati in India and became a follower. From this point on the teachings of both organisations became predominantly based on Advaita Vedanta.[5][6] He also provided guidance to the School of Meditation in Holland Park, London, from 1967 to his death.[7] For more than thirty years he passed on his teaching to the West. Before he died he wrote a letter to students in the West saying: "You have all that is needed to carry on, you need only to put what has been given into practice".[3]

Meanwhile, organizations which had been concerned with reviving the Jyotir Math in the 1930s reconvened and proposed Swami Krishnabodha Asrama as Shankaracharya despite Shantanand's claim and occupation of the Jyotir Math Shankaracharya-ship.[8] However, Krishnabodha died in 1973, and he nominated his disciple Swaroopananda Saraswati, a prior disciple of Brahmananda, as his successor. But because Shantananda still occupied the Jyotir Math ashram built by Brahmananda, Swaroopananda took residence in a nearby building or ashram instead.[8]

Sri Shantananda Saraswati's teachings continue to be widely studied in the West due to the guidance he provided the Study Society and the School of Economic Science, which both offer courses, teachings, lectures, and publications on the philosophy of non-duality. A contemporary well-known spiritual teacher to emerge from this tradition is Rupert Spira.[9] These schools are also responsible for the promulgation of a particular type of meditation, sometimes known as "transcendental meditation".[4] One celebrity who first learned to meditate in this context is Hugh Jackman.[10]

During his tenure, Shantanand was "supportive" of another Brahamananda disciple Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and "often appeared with him in public".[11][12] In 1961 he appeared at one of the Maharishi's training courses in Rishikesh and addressed the trainees, describing the meditation method as "the master key to the knowledge of Vedanta": "There are other keys, but a master key is enough to open all the locks".[13] In 1963 Sri Shantanand gave his support to the Marharishi's "All Indian Campaign".[13]

Finally, in 1980, Shantananda relinquished the Shankarcharya position to Dandi Swami Vishnudevananda, who held the position until his death in 1989.[14][13] Shantanand, in his capacity as senior Shankaracharya, then appointed Swami Vasudevananda Saraswati to the role.[2][3] Shantananda himself died in 1997.[2]

Teachings

editShantananda Saraswati taught that people should develop their spiritual life while fully engaged in worldly responsibilities, encouraging them to act to uplift their families, professions, communities, and to manifest the harmony, beauty, and efficiency of their spiritual practices in their everyday life.[3]

Sri Shantananda Saraswati (perhaps reflecting his experience as a husband and then a father) referred to love as "the natural in-between", a state of being that can always be availed because it lies within us all.[4]

Published discourses

edit- Good Company. ISBN 978-0-9561442-1-8

- Good Company II. ISBN 978-0-9547939-9-9

- The Man Who Wanted to Meet God: Myths and Stories That Explain the Inexplicable by His Holiness Shantanand Saraswati. ISBN 9781843336211

- Teachings of His Holiness Shantanand Saraswati. ISBN 978-0-9561442-9-4

References

edit- ^ Pasricha, Prem C. (1977) The Whole Thing the Real Thing, Delhi Photo Company, p. 71

- ^ a b c d Unknown author (2005) Indology The Jyotirmatha Shankaracharya Lineage in the 20th Century, retrieved 4 August 2012

- ^ a b c d e John, Adago (2018). East Meets West (2 ed.). Program Publishing. ISBN 978-0692124215.

- ^ a b c J., Snow, Michael (October 2018). Mindful philosophy. Milton Keynes. ISBN 9781546292388. OCLC 1063750429.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rawlinson, Andrew (1997). The book of enlightened masters : western teachers in eastern traditions. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 0812693108. OCLC 36900790.

- ^ Johanna, Petsche (2015). "Gurdjieffian Overtones in Leon MacLaren's School of Economic Science". International Journal for the Study of New Religions. 6 (2): 197–219. doi:10.1558/ijsnr.v6i2.28443.

- ^ W., Whiting, F. (1985). Being oneself : the way of meditation. School of Meditation. London: The School. ISBN 0951105604. OCLC 17234389.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Unknown author (5 May 1999) archived here Accessed: 2012-08-30. or here%5D The Monastic Tradition Advaita Vedanta web page, retrieved 28 August 2012

- ^ "About spiritual teacher, author and speaker | Rupert Spira".

- ^ "Oprah Talks to Hugh Jackman".

- ^ Mason (1994) p. 57 Note: "On Tuesday, 30 May 1961, eight years to the day after his master's death, the Shankaracharya of Jyotir Math, Swami Shantanand Saraswati graced the teacher training course with his presence and was received with all due ceremony. Arriving at the site where the new Academy was being built, he addressed the Maharishi and the gathered meditators . . . . He commended the practice of the Maharishi’s meditation, describing it as a 'master key to the knowledge of Vedanta' and added, 'There are other keys, but a master key is enough to open all the locks.’

- ^ name="Williamson">Williamson, Lola (2012) New York University Press, Transcendent In America, page 87

- ^ a b c Mason, Paul, 1952- (1994). The Maharishi : the biography of the man who gave transcendental meditation to the world. Shaftesbury, Dorset. ISBN 1852305711. OCLC 31133549.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Profile of Shankaracharya Swami Shantanand Saraswati - www.paulmason.info". www.paulmason.info. Retrieved 11 April 2019.