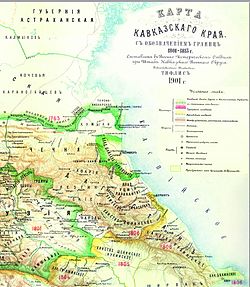

The Shamkhalate of Tarki, or Tarki Shamkhalate (also Shawhalate, or Shevkalate; Kumyk: Таргъу Шавхаллыкъ, romanized: Tarğu Şawhallıq)[2] was a Kumyk[a] state in the eastern part of the North Caucasus, with its capital in the ancient town of Tarki.[10] It formed on the territory populated by Kumyks[11] and included territories corresponding to modern Dagestan and adjacent regions. After subjugation by the Russian Empire, the Shamkhalate's lands were split between the Empire's feudal domain with the same name extending from the river Sulak to the southern borders of Dagestan, between Kumyk possessions of the Russian Empire and other administrative units.

Shamkhalate of Tarki Таргъу Шавхаллыкъ | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circa 8th century–1867 | |||||||||||||||

|

Reported flag[1] | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Status | Vilayet within: Ottoman Empire (1580s–1590s) Feudal domain within: Russian Empire (1813–1867) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tarki | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | circa 8th century | ||||||||||||||

• Abolishment of the Shamkhalate | 1867 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Russia | ||||||||||||||

At some point the Shamkhalate had vassals from the Caspian Sea to Kabarda and Balkaria. The Shamkhals also possessed the title of the Vali of Dagestan[12] and had their residence in the ancient Khazar-Kumyk mountainous shelter.[13]

Annexation of the Tarki Shamkhalate and other territories of Dagestan by Russia was concluded by the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. In 1867 the feudal domain of the Shamkhalate was abolished, and on its territory the Temir-Khan-Shura (now Buynaksk) district of Dagestan Oblast was established.[14]

During a short period in 1580-1590s the Shamkhalate was officially a part of the Ottoman Empire. Since the 16th century the state was a major figure of Russian politics to the southern borders, as it was the main target and obstacle in conquering the Caucasian region.[13]

Emergence of Shamkhalate

editArab version

editAccording to records from Arab sources, the Shamkhalate emerged in the year 734, when Arab conqueror Abu-Muslim appointed one of his generals named "Shakhbal" to rule over the "Kumuh region". This version is based upon "Derbend-name" source, which is by itself not known to have a certain author and has many anonymous undated versions. The most recent authored version is of the 16th century.

Critics of the Arab version

editV. Bartold also stated that the term "Shamkhal" is a later form of the original form "Shawkhal", which is mentioned both in the Russian[15] and Persian (Nizam ad-Din Shami and Sheref ad-din Yezdi) sources.[16] Dagestani historian Shikhsaidov wrote that the version claiming Arab descent was in favor of the dynasty and clerics (the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad).[17] A. Kandaurov wrote that the Arab version was elaborated by the Shamkhals themselves. Also, the title Shamkhals is not mentioned in the works of the Medieval Arabic historians and geographers.[18]

Turkic-Kumyk version

editAmong the supporters of the Turkic version of the creation of the Shamkhalian state is Lak historian Ali Kayaev:[19][20]

Shamkhal wasn't a descendant of Abbas Hamza but a Turk, who came with his companions. After him the Shamkhalate became a hereditary state.

It was supported by Turkish historian Fahreddin Kirzioglu,[21] the early 20th century historian D. H. Mamaev,[22] Halim Gerey Sultan,[23] Muhammed Efendi,[24] and others. Dagestanian historian R. Magomedov stated that:[25]

there is all necessary proofs to relate the term to the Golden Horde, but not to the Arabs. We may think that in the period of the Mongol-Tatars they put a Kumyk ruler in that status [Shamkhal].

Russian professor of oriental studies, the Doctor of Historical Sciences I. Zaytsev, also shared the opinion that the Shamkhalate was a Kumyk state with the capital in the town of Kumuk (written thus in medieval sources). While studying works of the Timurid historians Nizam ad-Din Shami and Sheref ad-din Yezdi, Soviet historians V. Romaskevich[26] and S. Volin,[26] and Uzbek historian Ashraf Ahmedov,[27] as well as professor in Alan studies O. Bubenok,[28] call Gazi-Kumuk (also Gazi-Kumukluk in medieval sources[29]) call the Shamkhalate area as the lands of Kumyks.

Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi called the Shamkhal "a natural Oghuz".[30] One of the arguments of the Turkic version is that Shamkhals were elected in the way that is traditional for Turkic peoples — tossing a red apple.[31] Ancient pre-Muslim names of the Kumuk [today Kumukh] inhabitants, as fixed in Khuduk inscription — Budulay, Ahsuwar, Chupan and others[32] — are of Turkic origin.[33] On the graves of the Shamkhals in Kumukh there are Turkic inscriptions, as noted by professor of Caucasian studies L. Lavrov.[34] The grave itself was called by the locals "Semerdalian" after the Khazar city of Semender;[35] the gravestones there are patterned in a Kipchak style.[36] In the "Maza chronicle" Shamkhals are described as "a branch of the Khan-Hakhan generations".[37] Nizam ad-Din Shami Yezdi in his 14th century Timurid chronicle The Book of Triumph[38] and Sheref ad-din Yezdi mentioned the land as Gazi-Kumukluk,[39] where the suffix "luk" is a Turkic linguistic sign.[40] The ruler of Andi people Ali-Beg, who founded a new ruling dynasty, also had a title of "Shamkhal".[41] According to the local story, starting from Ali-Beg until Khadjik, the rulers of their land spoke in the "language of the plains", i.e. Kumyk.[42]

Jamalutdin-haji Mamaev in the beginning of the 20th century wrote:[43]

The fact that the ruler in Dagestan was chosen from the Chinghiz dynasty and called shawkhal-khan [sic], derived from the Turkic, Tatar spiritual tradition, as a reliance on their genealogical ancestry (nasab), not paying attention to the science or courtesies (edeb). The house of Chinghiz is highly esteemed amongst them (shawkhals), as Quraysh amongst Muslims. They didn't allow someone to stand higher than them or lift heads.

According to French historian Chantal Lemercier-Quelquejay, Shamkhalate was dominated by the Turkic Kumyks, and the Lak people hold the honorable title of Gazis (because of the earlier adoption of Islam).[44] Apart from that, the Shamkhalate had a feudal class of Karachi-beks, a title exclusively related to Mongol-Turkic states.

Piano Karpini mentioned from his travels that Khazaria and Lak, even before falling in the hands of the "Western Tatars", belonged to the Cumans:[45]

The first King of the Western Tatars was Sain. He was strong and mighty. He conquered Russia, Comania, Alania, Lak, Mengiar, Gugia and Khazaria, and before his conquest, they all belonged to Comans.

Vasily Bartold also stated that the Arabic version is a compilation by local historians trying to merge legends with history.[16]

The original population of the "Kazi-Kumykskiy" possession, as wrote F. Somonovich in 1796, were Dagestan Tatars (Kumyks). After the resettlement of some Lezginian peoples from Gilan province of Persia, under the rule of Shamkhal, the population mixed, and the power of Shamkhal decreased, and the new population formed their own Khanate independent of the Shamkhal dynasty:[46]

The people of this province come from Dagestan Tatars, mixed with the Persian settlers; they follow the same [religious] law, and speak [one of the] Lezginian languages.

and

As some Persian sources say, this people settled here under the Abumuselim shah, from the Gilan Province and served under the cleric official kazi, under the rule of Shamkhal. Because of that cleric and the people of Kumukh place, who resettled here from Gilan, or, better said, by the mixture with the indigenous Kumukh people, who originate from Dagestan Tatars, the name Kazikumuk emerged. This clerics were the ancestors of Khamutay [contemporary Khan of Kazikumukh], who following the example of others claimed in their parts independence and in the present times adopted the Khan title.

History

edit16-17th cc.

editRelations with Russia

editIn 1556 diplomatic relations with the Moscow state were set. The peaceful embassy of shamkhal brought Ivan the Terrible a number of rich gifts, one of which was extraordinary: an elephant, not seen up to that time in Moscow.[47] Shamkhal's envoy to Russia had no success as in 1557 prince Temruk Idar of Kabardia asked Ivan the Terrible to help him against the raids of shevkalski tsar (shamkhal), Crimean khan and the Turks. Ivan the Terrible sent his general Cheremisov who took over Tarki but decided not to remain there.[48][49]

Russian fortresses

editIn 1566 prince Matlov of Kabarda asked the Moscow tsar to put a fortress at the confluence of the Sunzha and Terek. For the construction of the fortress "came princes Andrew Babichev and Peter Protasiev with many people, guns and musket". In 1567 trying to prevent the Russians to build their stronghold at the mouth of the Sunzha, Budai-shamkhal and his son Surkhay were killed on the battlefield as evidenced by their tombstones at the cemetery of shamkhals in Gazi-Kumukh.

In 1569 prince Chopan, son of Budai-shamkhal, was elected shamkhal. Territory of Chopan-shamkhal in the north extended beyond Terek river and adjoined the Khanate of Astrakhan. In the west his territory included part of Chechnya up to Kabarda. In the south, territories of Chopan-shamkhal extended "up to Shemakha itself" according to I. Gerber.[50]

In 1570 Chopan-shamkhal jointly with Turks and Crimeans undertook an expedition to capture Astrakhan. The city was not taken and the army retreated to Azov but then invaded Kabarda. Despite the demolition of the Sunzha fortress the Russian advance to the Caucasus by the end of the 1580s recommenced.[51][52]

In 1588, the Russian authorities at the mouth of the Terek founded the fortress of Terki, also known as the Terek Fortress. Terki became the main stronghold of the Russian army in northern Dagestan.

Alliance with Iran

editIn Persia in the court of the shah, shamkhal had an honorable place next to the shah. Sister of Chopan-shamkhal was married to shah Tahmasp I (1514–1576). "First of all, in Persia at the time of the great festivities there were made on the right and left side of Shah's throne, the two seats on each side for the four noble defenders of the state against the four strongest powers, namely: for the khan of Kandahar, as a defender against India; for shamkhal, as a defender against Russia; for the king of Georgian, as a defender of the state against the Turks; for the khan who lives on the Arab border". According to A. Kayaev, the influence of Chopan-shamkhal in Caucasus was great so that he "intervened in the affairs of succession of Persion throne in Iran".[53]

Alliance with Turkey

editIn 1577 Chopan-shamkhal jointly with his brother Tuchelav-Bek, Gazi-Salih of Tabasaran and in alliance with the Ottoman army undertook a military campaign against Qizilbashes who were defeated.[54][55] After the victory over Qizilbashes in Shirvan, Chopan-shamkhal carried out a visit to Turkey and was met in Eastern Anatolia with honors. Chopan-shamkhal was given many gifts. For his services in the war with the Persians shamkhal was given sanjak Shaburan and his brother Tuchelav sanjaks Akhty and Ikhyr. Ibrahim Peçevi reported that the governor of Shirvan Osman Pasha (also of Kumyk descent) married a daughter Tuchelav, a niece of Shamkhal.[56][57] Chopan Shamkhal pledged to defend Shirvan.

These relations led to the actual mutual agreement on the inclusion of Shamkhalate in the Ottoman Empire, while the Ottoman Sultan was already recognized as the caliph of all Muslims.[58]

Internal feuds and disintegration

editAt the end of the 16th century shamkhal feuded with krym-shamkhal (which was the title of Shamkhalian successor to the throne) who was supported by part of the "Kumyk land".

King Alexander of Kakheti reported at the time that "shamkhal affair was bad as they (shamkhal and krym-shamkhal) scold among themselves". In 1588 the Georgian ambassadors Kaplan and Hursh reported that shamkhalate was in turmoil and asked the Russian tsar to send troops as a measure of military action against the raids of shamkhal on Georgia.[59] Russians captured Tumen principality in the northern Dagestan.[60] In 1599 Georgian ambassadors in Moscow, Saravan and Aram, reported to king Alexander of Kakheti that it was difficult to reach shamkhal as he chose to reside in the mountains at the time:

"Neither you nor your men should be sent to fight shevkal (shamkhal), shevkal lives in the mountains, the road to him is narrow".

Georgian ambassador Cyril in 1603 reported in Moscow that "shevkal and his children live more in Gazi-Kumuk in the mountains, because that place is strong".[61]

By the end of the 16th through the beginning of the 17th centuries Shamkhalat, which was a major political entity in Caucasus, disintegrated into separate Kumyk fiefdoms.[62]

Defeating Russians

editIn 1594 a Khvorostinin's campaign into Dagestan took place, but his troops retreated. In 1604 a Buturlin's campaign into Dagestan took place. In 1605 Russian army that occupied lowlands of Kumykia (about 8,000 men) was surrounded and routed in the Battle of Karaman by the army of a Northern Kumyk prince Soltan-Mut of Endirey, some 20 kilometres north of Kumyk settlement of Anji, where today's Makhachkala is located.[63]

At the end of the 1640s, Shamkhal Surkhay III invited a smaller part of Nogai Horde, headed by Choban-Murza Ishterek, who did not want to obey the tsarist governors, to live in Shamkhalate. For his return to Russian borders, tsarist troops were sent to Kumykia with their Kabardian allies and Cossacks. In 1651 the Battle of Germenchik took place, where joint Kumyk-Nogai army secured a victory. In 1651, the Shamkhal wrote to the Astrakhan governors about a custom that “we, Kumyks, have and cherish our konaks [quests and friends] since the times of our fathers”, thus explaining their alliance with the Nogais.[64]

18th century, campaigns of Peter I and vassalage from Russia

editDuring the Persian campaign of Peter I, Schamkhalate started as an ally of Russia, but in 1725, shamkhal Adil-Girey II, incited by the Ottoman Empire, attacked the Russian fortress of the Holy Cross, was defeated, captured and sent into exile to the north of Russia. Despite fierce resistance, described as such by Russian companions of Peter I, particularly from the Endirey and Utamysh principalities,[65][66] Shamkhalat was defeated and on paper abolished. In 1734, after the Russian-Persian treaty, it was restored.

As a result of feudal civil strife and campaigns of Russian troops against Shamkhalat, at the beginning of the 18th century, only a small possession along the Caspian Sea (with a total area of up to 3 thousand km²) was all that remained from the state.

19th century, Caucasian War

editDuring the Caucasian War, at least three uprisings broke out in Shamkhalate — in 1823, 1831 and 1843.[67]

Population

editIt was a multiethnic state.[68] The main population was Kumyk.[69] At various times, it included some areas populated by Dargins,[70] and other peoples of the Caucasus.[71]

According to Russian sources of the late 18th century, the Tarki Shamkhalate, together with their vassals Akusha Dargins, had from 36 to 42 thousand households, numbering 98-100 thousand people of both genders.[72]

Known rulers

edit- Buday I, died in battle with the Russian army in Kabarda in 1566.

- Chopan-Shawkhal (1571–1588), actively participated in intra-Iranian internecine affairs, in the last years of his life he was an ally of the Ottoman Empire.

- Soltan-Mut of Tarki (circa 1560–1643) was a commander, under whom Northern Kumykia reached the peak of its power, for decades (late 16th – early 17th centuries) successfully repelling numerous attacks of neighbors, and defeating Russians at the Battle of Karaman.

- Adil-Gerey I (1609–1614), distinguished himself in the wars against Russia (especially in the battles near Boynak in 1594 and in the Karaman valley in 1605), adhered to the pro-Iranian political course.

- Surkhay III (1641–1667), pursued active foreign policy, won victories over Russian troops in the Battle of Germenchik and near Suyunch-Kala (Sunzha fortress) in 1651 and 1653 respectively.

- Budai II (1667–1692) distinguished himself in the wars with Iran and Russia (provided, in particular, active assistance to the Crimean Khans in their wars against Russia). He is also known for his patronage of the Old Believer Cossacks persecuted in Russia.

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Кумыкский мир | К истории государственной символики кумыков".

- ^ a b "Къумукъ Тил".

- ^ Советская Этнография, Изд-во Академии наук СССР, 1953 Цитата: Отдельные селения аварцев входили в ...кумыкское шамхальство Тарковское, кумыкское ханство Мехтулинское...

- ^ Гусейнов Гарун-Рашид Абдул-Кадырович Тюменское княжество в контексте истории взаимоотношений Астраханского ханства и Кумыкского государства с Русским в XVI в., Институт Истории АН РТ, Казань, 2012 Цитата: И в дальнейшем, о более северных затеречных, включавших и Тюменское княжество, ареальных пределах Кумыкского государства – шамхальства свидетельствуют сведения А.Олеария (1635-1639 гг.)

- ^ Документ из Российского государственного архива древних актов (фонд № 121 «Кумыцкие и тарковские дела»). Документы представляют из себя журнал, фиксирующий даты прибытия шамхальского посольства в Кремль

- ^ Современные проблемы и перспективы развития исламоведения, востоковедения и тюркологии

- ^ Дагестан в эпоху великого переселения народов: этногенетические исследования — Российская академия наук, Дагестанский науч. центр, Ин-т истории, археологии и этнографии, 1998 - Всего страниц: 191

- ^ Абдусаламов М.-П. Б. (2012). "Территория и население шамхальства Тарковского в трудах русских и западноевропейских авторов ХVIII–ХIХ вв" [The territory and population of Tarkovsky’s Shamkhalate in the works of Russian and Western European authors of the 18th–19th centuries] (PDF). Известия Алтайского государственного университета [News of Altai State University] (in Russian).

...четко выделил границы ряда кумыкских феодальных владений, в том числе шамхальства Тарковского...

[... clearly outlined the boundaries of a number of Kumyk feudal estates, including Tarkovsky’s Shamkhaldom...] - ^ Из истории русско-кавказскои воины: документы и материалы, А. М Ельмесов, Кабардино-Балкарское отд-ние Всероссииского фонда культуры, 1991, 261 pages, стр. 60 Цитата: ...и Крымскому, и к Шевкальскому (Кумыкское шамхальство — Э. А.)...

- ^ Упоминается в VIII веке в Вардапета Гевонда; писателя VIII века (1862). Истории халифов (in Russian). СПб. p. 28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Большая советская энциклопедия. — М.: Советская энциклопедия. 1969—1978. Цитата: феодальное владение в северо-восточной части Дагестана с центром Тарки. Образовалось в конце 15 в. на территории, населённой кумыками

- ^ "Газават.ру :: История - Былое и думы - ШАМХАЛЫ ТАРКОВСКИЕ".

- ^ a b Страница 58, 293 и другие. Белокуров С. А. Сношения России с Кавказом. — Выпуск 1-й. 1578—1613 гг. — М.: Университетская тип., 1889. — 715 с.

- ^ Шамхалы тарковские, ССКГ. 1868. Вып. 1. С. 58.

- ^ Belokurov, Sergey Alekseevich (2015). Russia's relations with the Caucasus (in Russian). Vol. 1.

- ^ a b Бартольд В.В. Сочинения. Т.III. Работы по исторической географии - Монография. М.: Наука, 1965 - С.412-413.

- ^ Шихсаидов А. Р. Дагестан в X—XIV вв. Махачкала, 1975.

- ^ Гусейнов Г-Р. А-К. Шавхал (Вопросы этимологии)// КНКО: Вести. Вып. № 6-7, 2001, Махачкала.

- ^ Али Каяев. Материалы по истории лаков. Рук. фонд. ИИЯЛ, д. 1642.

- ^ Советская Этнография, Изд-во Академии наук СССР, 1953 Цитата: Отдельные селения аварцев входили в ...кумыкское шамхальство Тарковское, кумыкское ханство Мехтулинское...

- ^ Çelik (Fahrettin M.). Kızılalmanın Türesini Yaşatan Şamkallar’ın Soyu // Çinaraltı, 1942, No.30, 31, 33

- ^ "История Кавказа и селения Карабудахкент" Джамалутдина-Хаджи Карабудахкентского / Под редакцией Г. М.-Р. Оразаева. Махачкала: ООО "Центр-полиграф", 2001.

- ^ Halim Gerey Soltan. Gulbin-i-Hanan. XVII y. Kirim ve Kafkas Tarihcesi // Emel, № 221. Temmuz-Agustots 1997.

- ^ Gulbin-i-Hanan. XVII y. (Ahmet Cevdet. Kirim ve Kafkas Tarihcesi // Emel, № 221. Temmuz-Agustot. 1997. S. 28) «После поражения Миран-Шаха от Аи Коюнлу кумыки "получили свою независимость, избрала себе хана из роди Чингизхана, которого величали по-своему "шаухал"»

- ^ Магомедов Р.М. Общественно-экономический и политический строй Дагестана в XVIII – начале XIX веков. Махачкала: Дагкнигоиздат, 1957. С. 145. «все основания отнести этот термин к Золотой Орде, нежели арабам. Можно считать, что правитель кумыков в период господства татаро-монгол ими выдвинут в этот сан»

- ^ a b Сборник материалов, относящихся к истории Золотой Орды, том II. Извлечения из персидских сочинений, собранные В. Г. Тизенгаузеном. М.-Л. АН СССР. 1941

- ^ Шараф ад-Дин Йазди. Упоминание о походе счастливого Сахибкирана в Симсим и на крепости неверных, бывших там // Зафар-наме (Книга побед Амира Темура (сер. XV в.), в варианте перевода с персидского на староузбекский Муххамадом Али ибн Дарвеш Али Бухари (XVI в.)) / Пер. со староузбек., предисл., коммент., указатели и карта А. Ахмедова. — Академия наук Республики Узбекистан. Институт востоковедения имени Абу Райхана Беруни. — Ташкент: «SAN’AT», 2008. - С.421

- ^ О. Б. Бубенок - АЛАНЫ-АСЫ В ЗОЛОТОЙ ОРДЕ (XIII-XV ВВ.) ; Нац. акад. наук Украины, Ин-т востоковедения им. А. Крымского

- ^ НИЗАМ АД-ДИН ШАМИ. "ЗАФАР-НАМЭ VIII". < КНИГА ПОБЕД (in Russian).

- ^ Эвлия Челеби. Книга путешествий. Выпуск 2. — М., 1979. — С. 794.

- ^ Gulbin-i-Hanan. XVII y. (Ahmet Cevdet. Kirim ve Kafkas Tarihcesi // Emel, No. 221. Temmuz-Agustot. 1997.

- ^ Аликберов А. К. Эпоха классического ислама на Кавказе: Абу Бакр ад-Дарбанди и его суфийская энциклопедия «Райхан ал-хака’ик» (XI—XII вв.) / А. К. Аликберов. Ответственный редактор С. М. Прозоров — М.: Вост. лит., 2003.

- ^ К.С. Кадыраджиев. Проблемы сравнительно-исторического изучения кумыкского и тюркского языков. Махачкала, ДГПУ, 1998 - 366с.

- ^ Лавров Л.И -Эпиграфические памятники Северного Кавказа на арабском, персидском и турецком языках. Памятники письменности Востока. - Москва: Наука - 1966 -

- ^ Булатова А.Г. Лакцы. Историко-этнографические очерки. Махачкала, 1971

- ^ Шихсаидов А.Р - Эпиграфические памятники Дагестана - М., 1985

- ^ "Maza chronicles".

- ^ Низам Ад-Дин Шами. "Книга Побед".

- ^ Шереф-ад-Дин Йезди. "Книга Побед".

- ^ К.С. Кадыраджиев. Проблемы сравнительно-исторического изучения кумыкского и тюрского языков. Махачкала, ДГПУ, 1998 - 366с.

- ^ Повествование об Али-Беке Андийском и его победе над Турулавом б. Али-Ханом Баклулальским как источник по истории Дагестана XVII века// Общественный строй союзов сельских общин Дагестана в XVIII - начале XIX веков. Махачкала, 1981. С. 132

- ^ Повествование об Али-Беке Андийском и его победе над Турулавом б. Али-Ханом Баклулальским как источник по истории Дагестана XVII века// Общественный строй союзов сельских общин Дагестана в XVIII - начале XIX веков. Махачкала, 1981. С. 132

- ^ "История Кавказа и селения Карабудахкент" Джамалутдина-Хаджи Карабудахкентского / Под редакцией Г. М.-Р. Оразаева. Махачкала: ООО "Центр-полиграф", 2001. С. 55

- ^ Шанталь Лемерсье-Келкеже. Социальная, политическая и религиозная структура Северного Кавказа в XVI в. // Восточная Европа средневековья и раннего нового времени глазами французских исследователей. Казань. 2009. С.272-294.

- ^ Кавказ: европейские дневники XIII–XVIII веков / Сост. В. Аталиков. - Нальчик: Издательство М. и В. Котляровых, 2010. 304 с., стр. 6-7

- ^ Описание Южного Дагестана Федором Симоновичем в 1796 году "Д". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ С. А. Белокуров. Сношения России с Кавказом — М., 1888. 4.1. С. 29, 58-60.

- ^ ПСРЛ. Т. XIII. 2-я пол. С. 324, 330.

- ^ Р. Г. Маршаев. Казикумухское шамхальство в русско-турецких отношениях во второй половине XVI — начале XVII вв. — М., 1963

- ^ В. Г. Гаджиев. Сочинение И. Г. Гербера «Описание стран и народов между Астраханью и рекою Курою находящихся» как исторический источник по истории народов Кавказа. – М., Наука, 1979.

- ^ Н. А. Смирнов. Россия и Турция в 16.-17 вв. М., 1946. С. 127

- ^ ЦГАДА. Крымские дела. Кн. 13. — Л. 71 об.

- ^ И. Г. Гербер. Известия о находящихся на западной стороне Каспийского моря между Астраханью и рекою Курою народах и землях и о их состоянии в 1728г. // "Сочинения и переводы, к пользе и увеселению служащие". СПб. 1760, с.36-37.

- ^ Нусрет-наме Кирзиоглу Ф. Указ. соч. С.279

- ^ Эфендиев О. Азербайджанское государство сефевидов в XVI веке. Баку. 1981. С. 15. 156.

- ^ Алиев К.М. В начале было письмо Газета Ёлдаш. Времена 13.04.2012.

- ^ Всеобщее историко-топографическое описание Кавказа (XVIII в.). 1784 г.

- ^ Камиль Алиев, Об исторических связях между Дагестаном и Турцией, начавшихся более 500 лет назад. Газета „Ёлдаш/Времена“ от 16,23,30 марта 2012

- ^ С. А. Белокуров. Указ. соч. С. 58–59.

- ^ Лавров Л. И. Кавказская Тюмень // Из истории дореволюционного Дагестана. М. 1976, с. 163-165. Lavrov defined Tumen as "an ancient Kumyk possession with seaside town of Tumen, which consisted of a mixed population of Kumyks, Kabardins, Nogais, Astrakhans, Kazan Tatars and Persians". The possession of Tumen was located near Sulak river in Dagestan and refers to the possession of Tumen mentioned by Khalifa ibn Hayyat in the 8th century. As it was reported, warlord Marwan capturing Gumuk and Khunzakh, headed north, towards the possession of Tumen. Bakikhanov links Tumen with 'Tumen-shah' in the eastern sources. (Бейлис В. М. Сообщения Халифы ибн Хаййата ал-Усфури об арабо-хазарских войнах в VII - первой половине VIII в. // Древнейшие государства Восточной Европы. 1998. М.,2000. С.43).

- ^ Белокуров С. Указ. раб. С. 302, 405.

- ^ "Распад шамхальства и образование кумыкских феодальных владений: причины и последствия". Гуманитарные, Социально-Экономические И Общественные Науки (8): 111–115. 2015.

- ^ Н. М. Карамзин. История государства Российского. Т.XI. Кн. III.)

- ^ Д. С. Кидирниязов, Ж. К. Мусаурова — Очерки истории ногайцев XV-XVIII вв. — Изд-во дом "Народы Дагестана", 2003 - С. 199

- ^ Голиков И. И. Деяния Петра Великого, мудрого преобразителя России, собранные из достоверных источников. — Изд. 2-е, М.: Типография Н. Степанова, 1838.

- ^ Походный журнал 1722 года. — СПб., 1855

- ^ Н.И. Покровский. Кавказские войны и имамат Шамиля. – Москва: «Российская политическая энциклопедия» (РОССПЭН), 2000.

- ^ Народы Центрального Кавказа и Дагестана: этнополитические аспекты взаимоотношений (XVI—XVIII вв.), Р. М. Бегеулов, 2005

- ^ Б. Г. Алиев, М.-С. К. Умаханов. Историческая география Дагестана XVII — нач. XIX в / А. И. Османов (ответ. редактор), М. М. Гусаев, А. Р. Шихсаидов. — Институт ИАЭ ДНЦ РАН, Издательство типографии ДНЦ РАН, 1999. — С. 218.

Основное население Шамхальства составляли кумыки. Единственное, что можно сказать, что села Губден и Кадар были даргинскими по этнической принадлежности и это не мешало им сохранять свою культуру, сотрудничать с кумыками, выполняя просьбы иля советы тарковских правителей. Губден и Тарки были тесно связаны еще до распада Казикумухского шамхальства.

- ^ Б. Г. Алиев, М.-С. К. Умаханов. Историческая география Дагестана XVII — нач. XIX в / А. И. Османов (ответ. редактор), М. М. Гусаев, А. Р. Шихсаидов. — Институт ИАЭ ДНЦ РАН, Издательство типографии ДНЦ РАН, 1999. — С. 218.

Основное население Шамхальства составляли кумыки. Единственное, что можно сказать, что села Губден и Кадар были даргинскими по этнической принадлежности и это не мешало им сохранять свою культуру, сотрудничать с кумыками, выполняя просьбы иля советы тарковских правителей. Губден и Тарки были тесно связаны еще до распада Казикумухского шамхальства.

- ^ ароды Центрального Кавказа и Дагестана: этнополитические аспекты взаимоотношений (XVI—XVIII вв.), Р. М. Бегеулов, 2005

- ^ Бутков П. Г. Сведения о силах, числе душ и деревень в Дагестане. 1795 / ИГЭД. — 1958.