Scottish literature in the nineteenth century includes all written and published works in Scotland or by Scottish writers in the period. It includes literature written in English, Scottish Gaelic and Scots in forms including poetry, novels, drama and the short story.

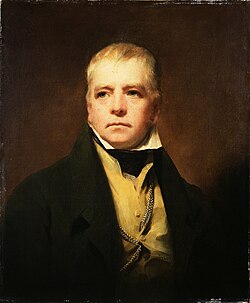

The most successful literary figure of the era, Walter Scott, began his literary career as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century, with Scots language poetry criticised for its use of parochial dialect and English poetry for its lack of Scottishness. Successful poets included William Thom, Lady Margaret Maclean Clephane Compton Northampton and Thomas Campbell. Among the most influential poets of the later nineteenth were James Thomson and John Davidson. The Highland Clearances and widespread emigration weakened Gaelic language and culture and had a profound impact on the nature of Gaelic poetry. Particularly significant was the work of Uilleam Mac Dhun Lèibhe, Seonaidh Phàdraig Iarsiadair and Màiri Mhòr nan Óran.

There was a tradition of moral and domestic fiction in the early nineteenth century that included the work of Elizabeth Hamilton, Mary Brunton and Christian Johnstone. The outstanding literary figure of the early nineteenth century was Walter Scott, whose Waverley is often called the first historical novel. He had a major worldwide influence. His success led to a publishing boom in Scotland. Major figures that benefited included James Hogg, John Galt, John Gibson Lockhart, John Wilson and Susan Ferrier. In the mid-nineteenth century major literary figures that contributed to the development of the novel included David Macbeth Moir, John Stuart Blackie, William Edmondstoune Aytoun and Margaret Oliphant. In the late nineteenth century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations, including Robert Louis Stevenson and Arthur Conan Doyle, whose Sherlock Holmes stories helped found the tradition of detective fiction. In the last two decades of the century the "kailyard school" (cabbage patch) depicted Scotland in a rural and nostalgic fashion, often seen as a "failure of nerve" in dealing with the rapid changes that had swept across Scotland in the industrial revolution. Figures associated with the movement include Ian Maclaren, S. R. Crockett and J. M. Barrie, best known for his creation of Peter Pan, which helped develop the genre of fantasy, as did the work of George MacDonald.

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. Scott was keenly interested in drama, writing five plays. Also important was the work of Joanna Baillie. These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century. Despite these successes, provincialism began to set in to Scottish theatre. A number of figures that could have made a major contribution to Scottish drama moved south to London. Many poems and novels were original serialised in periodicals, which included The Edinburgh Review and Blackwood's Magazine. They also played a major role in the development of the short story.

Poetry

editScottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century, with Scots language poetry criticised for its use of parochial dialect and English poetry for its lack of Scottishness.[1] Conservative and anti-radical Burns clubs sprang up around Scotland, filled with members who praised a sanitised version of Robert Burns' life and work and poets who fixated on the "Burns stanza" as a form. William Tennant's (1784–1848) "Anster Fair" (1812) produced a more respectable version of folk revels.[2] Scottish poetry has been seen as descending into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popular Whistle Binkie anthologies, which appeared 1830–90 and which notoriously included in one volume "Wee Willie Winkie" by William Miler (1810–72).[2] This tendency has been seen as leading late nineteenth-century Scottish poetry into the sentimental parochialism of the Kailyard school.[3]

However, Scotland continued to produce talented and successful poets. Walter Scott's (1771–1832) literary career began with ballad collecting and poetry, with highly successful works such as the narrative poem The Lady of the Lake (1810), which made him the most popular poet until his place was taken by Byron and he moved towards the writing of prose.[4] Poets from the lower social orders included the weaver-poet William Thom (1799–1848), whose his "A chieftain unknown to the Queen" (1843) combined simple Scots language with a social critique of Queen Victoria's visit to Scotland. From the other end of the social scale Lady Margaret Maclean Clephane Compton Northampton (d. 1830), translated Jacobite verse from the Gaelic and poems by Petrarch and Goethe as well as producing her own original work. William Edmondstoune Aytoun (1813–65), eventually appointed Professor of belles lettres at the University of Edinburgh, he is best known for The lays of the Scottish Cavaliers and made use of the ballad form in his poems, such as Bothwell. Among the most successful Scottish poets was the Glasgow-born Thomas Campbell (1777–1844), whose produced patriotic British songs, among them was "Ye Mariners of England", a reworking of "Rule Britannia!", and sentimental but powerful epics on contemporary events, including Gertrude of Wyoming. His works were extensively reprinted in the period 1800–60.[1]

Among the most influential poets of the later nineteenth century who rejected the limitations of the Kailyard School were James Thomson (1834–82), whose "City of Dreadful Night" broke many of the conventions of nineteenth-century poetry and John Davidson (1857–1909), whose work, including "The Runable Stag" and "Thirty Bob a Week" were much anthologised, would have a major impact on modernist poets including Hugh MacDiarmid, Wallace Stevens and T. S. Eliot.[3]

The Highland Clearances and widespread emigration significantly weakened Gaelic language and culture and had a profound impact on the nature of Gaelic poetry. The best poetry in this vein contained a strong element of protest, including Uilleam Mac Dhun Lèibhe's (William Livingstone, 1808–70) objection to the Islay clearances in "Fios Thun a' Bhard" ("A Message for the Poet") and Seonaidh Phàdraig Iarsiadair's (John Smith, 1848–81) long emotional condemnation of those responsible for the clearances Spiord a' Charthannais. The best known Gaelic poet of the era was Màiri Mhòr nan Óran (Mary MacPherson, 1821–98), whose verse was criticised for a lack of intellectual weight, but which embodies the spirit of the land agitation of the 1870s and 1880s and whose evocation of place and mood has made her among the most enduring Gaelic poets.[5]

Novel

editAs elsewhere in the British Isles there was a tradition of moral and domestic fiction in the early nineteenth century. It did not flourish to the same extent in Scotland, but did produce a number of significant publications. These included Elizabeth Hamilton's (1756?–1816), Cottagers of Glenburnie (1808), Mary Brunton's (1778–1818) Discipline (1814) and Christian Johnstone's Clan-Albin (1815).[6]

Walter Scott's first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel, and launched a highly successful career as a novelist.[7] His early work dealt with Scottish history, particularly of the Highlands and Borders and included Rob Roy (1817) and The Heart of Midlothian (1818). Beginning with Ivanhoe (1820) he turned to English history and began the European vogue for his work.[8] He did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century.[9] He is considered the first novelist writing in English to enjoy an international career in his own lifetime,[10] having a major influence on novelists in Italy, France, Russia and the US as well as Great Britain.[8]

Scott's success led to a publishing boom that benefitted his imitators and rivals. Scottish publishing increased threefold as a proportion of all publishing in Great Britain, reaching a peak of 15 per cent in 1822–25.[6] The major figures that benefited from this boom included James Hogg (1770–1835), whose best known work is The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), which dealt with the themes of Presbyterian religion and Satanic possession, evoking the landscape of Edinburgh and its surrounding environment.[11] John Galt's (1779–1839) most famous work was Annals of the Parish (1821), given in the form of a diary kept by a rural minister over a fifty-year period and allowing Galt to make observations about the changes in Scottish society.[12] Walter Scott's son-in-law John Gibson Lockhart (1794–1854), is most noted for his Life of Adam Blair (1822), which focuses on the contest between desire and guilt.[12] The lawyer and critic John Wilson, as Christopher North, published novels including Lights and Shadows of Scottish Life (1822), The Trials of Margaret Lyndsay (1823) and The Foresters (1825), which investigated individual psychology.[13] The only major female novelist to emerge in the aftermath of Scott's success was Susan Ferrier (1782–1854), whose novels Marriage (1818), The Inheritance (1824) and Destiny (1831), continued the domestic tradition.[6]

In the mid-nineteenth century major literary figures that contributed to the development of the novel included David Macbeth Moir (1798–1851), John Stuart Blackie (1809–95) and William Edmondstoune Aytoun (1813–65).[12] Margaret Oliphant (1828–97) produced over a hundred novels, many of them historical or studies of manners set in Scotland and England,[14] including The Minister's Wife (1886) and Kirsteen (1890). Her series the Chronicles of Carlingford has been compared with the best work of Anthony Trollope.[15]

In the late nineteenth century, a number of Scottish-born authors gained international reputations. Robert Louis Stevenson's (1850–94) work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), which explored the psychological consequences of modernity. Stevenson was also crucial to the further development of the historical novel with historical adventures in books such as Kidnapped (1886) and Treasure Island (1893) and particularly The Master of Ballantrae (1888), which used historical backgrounds as a mechanism for exploring modern concerns through allegory.[14] Arthur Conan Doyle's (1859–1930) Sherlock Holmes stories produced the archetypal detective figure and helped found the tradition of detective fiction.[14]

In the last two decades of the century the "kailyard school" (cabbage patch) depicted Scotland in a rural and nostalgic fashion, often seen as a "failure of nerve" in dealing with the rapid changes that had swept across Scotland in the industrial revolution. Figures associated with the movement include Ian Maclaren (1850–1907), S. R. Crockett (1859–1914) and J. M. Barrie (1860–1937), best known for his creation of Peter Pan, which helped develop the genre of fantasy.[14] Also important in the development of fantasy was the work of George MacDonald (1824–1905) whose produced children's novels, including The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and At the Back of the North Wind (1872), realistic novels of Scottish life, but also Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858) and later Lilith: A Romance (1895), which would be an important influence on the work of both C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien.[14]

Drama

editScottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage.[16] This was largely historical in nature and based around a core of adaptations of Scott's Waverley novels.[16] Scott was keenly interested in drama, becoming a shareholder in the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh.[17] Scott also wrote five plays, of which Hallidon Hill (1822) and MacDuff's Cross (1822) were patriotic Scottish histories.[17] Adaptations of the Waverley novels, first performed primarily in minor theatres, rather than the larger Patent theatres, included The Lady in the Lake (1817), The Heart of Midlothian (1819) (specifically described as a "romantic play" for its first performance), and Rob Roy, which underwent over 1,000 performances in Scotland in this period. Also adapted for the stage were Guy Mannering, The Bride of Lammermoor and The Abbot. These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century.[18]

Also important was the work of Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), although her work was more significant anonymously in print than performance for much of her lifetime, she emerged as one of Scotland's leading playwrights. Baillie's first volume of Plays on the Passions was published in 1798 consisted of Count Basil, a tragedy on love, The Tryal, a comedy on love, and De Monfort, a tragedy on hatred. De Monfort was successfully performed in Drury Lane, London before knowledge of her identity emerged and the prejudice against women playwrights began to effect her career.[19] Baillie's Highland themed Family Legend was first produced in Edinburgh in 1810 with the help of Scott, as part of a deliberate attempt to stimulate a national Scottish drama.[20] Locally produced drama in this period included John O' Arnha, adapted from the poem by George Beattie by actor-manager Charles Bass and poet James Bowick for the Theatre Royal in Montrose in 1826. A local success, Bass also took the play to Dundee and Edinburgh.[21]

Despite these successes, provincialism began to set in to Scottish theatre. By the 1840s, Scottish theatres were more inclined to use placards with slogans such as "the best company out of London", rather than producing their own material.[22] In 1893 in Glasgow there were five productions of Hamlet in the same season.[23] In the second half of the century the development of Scottish theatre was hindered by the growth of rail travel, which meant English tour companies could arrive and leave more easily for short runs of performances.[24] A number of figures that could have made a major contribution to Scottish drama moved south to London, including William Sharp (1855–1905), William Archer (1856–1924) and J. M. Barrie.[23]

Periodicals and the short story

editIn the first half of the century, the major publishing format in Britain was the periodical. As a result of its rise, the essay was the dominant and most marketable literary form for two decades at the beginning of the century. The template for quarterly periodicals was set by The Edinburgh Review, founded in Edinburgh in 1802 by four Whig lawyers with literary aspirations. Contributors were well paid and its paper covers, article lengths and formats, would be much copied. The most important rival was published by Tory William Blackwood, Walter Scott's publisher. It was known as Blackwood's Magazine, but was founded as the Edinburgh Monthly Magazine in 1817 and later shortened to Maga. Blackwood's inclusion of scathing literary reviews resulted in a large number of lawsuits that disrupted its publication, but ensured its literary reputation. The magazine entered into an acrimonious rivalry with the London Magazine, founded by Aberdeenian John Scott (1781–1821), that ended in a duel that resulted in Scott's death in 1821.[25]

Blackwood pioneered the publication of novels that were originally serialised in periodicals.[25] The periodicals had a major impact on the development of British literature in the era of Romanticism, helping to solidify the literary respectability of the novel, which were heavily reviewed in their pages.[26][27] They also played a major role in the development of the short story.[2] Publications included work by Scott, Galt and Hogg, as well as writers from outwith Scotland such as Charles Dickens, Emily Brontë, Robert Browning, and Edgar Allan Poe and lesser known figures including William Mudford, William Godwin and Samuel Warren.[28] These particularly focusing on the new Gothic genre, which consisted of exotic, supernatural country tales, which appealed to a new urban population displaced by the Industrial Revolution.[2]

Notes

edit- ^ a b L. Mandell, "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed., The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748624813, pp. 301–07.

- ^ a b c d G. Carruthers, Scottish Literature (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), ISBN 074863309X, pp. 58–9.

- ^ a b M. Lindsay and L. Duncan, The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-century Scottish Poetry (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), ISBN 074862015X, pp. xxxiv–xxxv.

- ^ A. Calder, Byron and Scotland: Radical Or Dandy? (Rowman & Littlefield, 1989), ISBN 0389208736, p. 112.

- ^ J. MacDonald, "Gaelic literature", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 255–7.

- ^ a b c I. Duncan, "Scott and the historical novel: a Scottish rise of the novel", in G. Carruthers and L. McIlvanney, eds, The Cambridge Companion to Scottish Literature (Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2012), ISBN 0521189365, p. 105.

- ^ K. S. Whetter, Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6142-3, p. 28.

- ^ a b G. L. Barnett, ed., Nineteenth-Century British Novelists on the Novel (Ardent Media, 1971), p. 29.

- ^ N. Davidson, The Origins of Scottish Nationhood (Pluto Press, 2008), ISBN 0-7453-1608-5, p. 136.

- ^ R. H. Hutton, Sir Walter Scott (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 1108034675, p. 1.

- ^ A. Maunder, FOF Companion to the British Short Story (Infobase Publishing, 2007), ISBN 0816074968, p. 374.

- ^ a b c I. Campbell, "Culture: Enlightenment (1660–1843): the novel", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 138–40.

- ^ G. Kelly, English Fiction of the Romantic Period, 1789–1830 (London: Longman, 1989), ISBN 0582492602, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e C. Craig, "Culture: age of industry (1843–1914): literature", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 149–51.

- ^ A. C. Cheyne, "Culture: Age of Industry (1843–1914), general", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 143–6.

- ^ a b I. Brown, The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748624813, pp. 229–30.

- ^ a b I. Brown, The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748624813, pp. 185–6.

- ^ I. Brown, The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748624813, p. 231.

- ^ B. Bell, "The national drama and the nineteenth century" I. Brown, ed, The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), ISBN 0748641076, pp. 48–9.

- ^ M. O'Halloran, "National Discourse or Discord? Transformations of The Family Legend by Baille, Scott and Hogg", in S-R. Alker and H. F. Nelson, eds, James Hogg and the Literary Marketplace: Scottish Romanticism and the Working-Class Author (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009), ISBN 0754665690, p. 43.

- ^ B. Bell, "The national drama and the nineteenth century" I. Brown, ed, The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011) ISBN 0748641076, p. 55.

- ^ H. G. Farmer, A History of Music in Scotland (Hinrichsen, 1947), ISBN 0-306-71865-0, p. 414.

- ^ a b B. Bell, "The national drama and the nineteenth century" I. Brown, ed, The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011) ISBN 0748641076, p. 57.

- ^ P. Maloney, Scotland and the Music Hall 1850–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), ISBN 0719061474, p. 8.

- ^ a b D. Finkelstein, "Periodical, encyclopaedias and nineteenth-century literary production", in I. Brown, ed., The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748624813, pp. 201–07.

- ^ A. Jarrels, "'Associations respect[ing] the past': Enlightenment and Romantic historicism", in J. P. Klancher, A Concise Companion to the Romantic Age (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), ISBN 0631233555, p. 60.

- ^ A. Benchimol, ed., Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), ISBN 0754664465, p. 210.

- ^ R. Morrison and C. Baldick, eds, Tales of Terror from Blackwood's Magazine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), ISBN 0192823663.