Santiago Salvador Franch (1864–1894) was a Spanish anarchist terrorist, known for carrying out the Liceu bombing, which killed at least 20 people. Originally from a Traditionalist Catholic background, having grown up in rural Aragon, Salvador was exposed to anarchism after arriving in the Catalan capital of Barcelona. There he came under the influence of Paulí Pallàs, who was executed for carrying out a bombing attack in the city. In revenge for the execution, Salvador carried out the bombing of the city's Lyceum Theatre. He managed to get away and enjoy the panic his attack had caused. After two months in hiding, he was arrested in Zaragoza and confessed to sole responsibility for the attack. During his imprisonment, he falsely converted back to Catholicism in order to get preferential treatment. After he was sentenced to execution, he renounced his conversion and proclaimed his loyalty to anarchism. Salvador was garroted in El Raval, where his body was displayed as a warning to other would-be anarchist terrorists.

Santiago Salvador | |

|---|---|

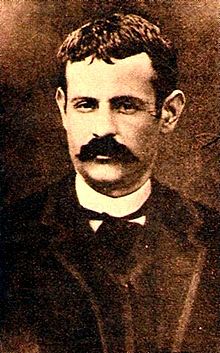

Salvador, c. 1890 | |

| Born | Santiago Salvador Franch 1864 |

| Died | 21 November 1894 (aged 29–30) |

| Cause of death | Execution by garrote |

| Known for | Liceu bombing |

| Movement | Anarchism in Spain |

Biography

editEarly life and activism

editSantiago Salvador was born in the town of Castelserás in 1864. From an early age, Salvador struggled fiting into Spanish society.[1] He grew up among extreme poverty and violence in rural Aragon, where the ideologies of monarchism and Catholicism dominated his upbringing.[2] After experiencing difficulties with his family, he left home at the age of fourteen.[1] In 1881, at the age of sixteen, he escaped to the Catalan capital of Barcelona, where he found a job as a domestic worker. He settled permanently in the city,[2] later finding work selling contraband wine.[3] In 1891, he married Antònia Colom i Vicens, who gave birth to a daughter in November 1892.[2]

Throughout most of his life, until the age of 29, he was a committed Carlist, part of a Traditionalist Catholic movement which supported the claim of the House of Bourbon-Parma to the Spanish throne. But according to the criminologist Cesare Lombroso, Salvador's religious fanaticism was soon replaced with anarchist extremism.[1] Salvador learned about this new political philosophy by reading the anarchist publications sold on La Rambla. He also attended rallies, where he heard the Catalan anarchist Paulí Pallàs speak.[4] The two became fast friends, sharing anarchist literature with each other, and Salvador joined Pallàs' affinity group Benvenuto. Salvador was drawn further into the movement, only associating with other anarchists and losing interest in any activity other than reading and discussing literature.[5]

Liceu bombing

editWhen Pallàs was arrested and tried for carrying out a bombing attack on Gran Via, Salvador followed the case closely.[5] Pallàs was sentenced to execution, which deeply affected Salvador. He began developing a plan to avenge Pallàs' death by carrying out an attack against the Catalan bourgeoisie, seeking to terrorise those who had celebrated the execution.[6] On 7 December 1893, Salvador took two Orsini bombs to the Liceu theatre; with a peseta his wife had given him to buy salt, he bought a cheap ticket for a seat on the fifth floor.[5] During the second act, he threw the bombs over the balcony into the crowd below, killing 20 people and wounding up to 35 others.[7] The explosion caused panic among the theatre-goers, which gave Salvador cover for his escape. He found joy in the fear he saw in the eyes of the authorities, the clergy and the bourgeoisie.[5]

The following day, he went for a casual walk in the city and visited some of his anarchist comrades. When he bragged to them about the bombing, his friends were shocked and tried get rid of him. He mocked them for lacking "character" and "courage", while he had sacrificed his life in the pursuit of social progress. Later that evening, he told his wife about the attack, causing her to break down in tears.[8] Taking pride in his attack, Salvador eagerly read newspaper accounts of the bombing, delighting in the panic expressed in the press.[9]

On the second day after the bombing, a funeral procession of the victims made its way from the Old Hospital de la Santa Creu to the Columbus Monument at the end of La Rambla.[10] Salvador asked his comrades to give him more bombs, which he planned to use to attack the bourgeoisie attending the funeral. Not wanting to give him any, they claimed they did not have any bombs left. He again chastised them for lacking courage.[11] When Salvador attended the funeral at the Columbus Monument and saw many figures from high society in attendance, including the Captain General of Catalonia Arsenio Martínez Campos, he lamented that he had missed a "manificent occasion to throw more bombs".[12]

Arrest, imprisonment and execution

editOn New Year's Day of 1894, while Salvador was in bed at his cousin's apartment in Zaragoza, near the Cathedral of the Saviour, the Civil Guard burst into his room. He quickly grabbed a flask of poison and attempted to drink it, but the Civil Guards prevented him and shot him in the hip. Salvador quickly confessed to sole responsibility for the bombing; by this time, several anarchists had already been tortured into giving forced confessions for the attack.[13] Despite his confession, in May 1894, six other anarchists were convicted and executed for their suspected role in the bombing.[14]

Salvador spent his final months in the Reina Amalia prison, in El Raval.[15] By August 1894, Salvador was claiming to have renounced anarchism and re-converted to Catholicism. He accepted communion and expressed a desire to join the Franciscans, which gained him support from many Catholics, who fully believed that his conversion was sincere. His portrait was widely distributed by Catholic organisations, leading to a ban on the publication of his image.[16] When the prosecutor ordered the revocation of the special treatment he had received after his conversion, Salvador lost his temper, implying that his conversion had been insincere.[17] Salvador was finally convicted under a retroactive application of new anti-anarchist laws, introduced in July 1894, which imposed capital punishment on anarchists that carried out bombing attacks.[18] After he received his death sentence, he again renounced Catholicism. He admitted to a Jesuit priest that he had faked his conversion, prompting the Archbishop of Barcelona Jaume Català to call off alms collections for Salvador.[17]

His final days were constantly reported on by the Catalan newspaper El Noticiero Universal, which noted his choice of breakfast (fried eggs, bread and wine) on the day before his execution; described the furniture in his cell and even tracked his pulse and temperature. When the director of the paper visited him, Salvador asked him to donate 200 pesetas of the profits reports of his execution were generating to his daughter.[19] He spent his final night with priests by his bedside. At 03:00, on 21 November 1894, thousands of people began to gather around the execution platform, in the courtyard of the Reina Amalia prison. At 08:00, Salvador was led out into the courtyard, where he was surrounded by police and spectators, with even nearby terraces and balconies providing viewing points. Due to the gunshot in his hip, he was unsteady as he climbed the stairs to the platform. When he noticed there were cameras fixed on him, he straightened his posture and shouted "Long live the social revolution! Long live anarchy! Death to all religions!" He then sang the first verse of the anarchist song Hijos del Pueblo.[19]

He asked the executioned to kill him quickly. He was put in the garrote and his last words were "Health, justice and love" before he was strangled to death. His body was left on the platform until 16:00, in order to send a message to the anarchist movement.[20] Anarchist bombings in Spain continued into the 20th century.[21] Salvador's wife Antònia Colom i Vicens was arrested and imprisoned following the 1896 Barcelona Corpus Christi procession bombing.[22]

References

edit- ^ a b c Jensen 2016, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Bray 2022, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 56–57; Jensen 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 57; Jensen 2016, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Bray 2022, p. 57.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 57; Jensen 2016, p. 45.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 58.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 64.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 65.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 77.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 96.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 81.

- ^ a b Bray 2022, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Jensen 2016, p. 37.

- ^ a b Bray 2022, p. 83.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Bray 2022, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Bray 2022, p. 100.

Bibliography

edit- Bray, Mark (2022). The Anarchist Inquisition: Assassins, Activists, and Martyrs in Spain and France. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501761928. LCCN 2021038606.

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2016). "Historical lessons: An overview of early anarchism and lone actor terrorism". In Fredholm, Michael (ed.). Understanding Lone Actor Terrorism. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315657622-2 (inactive 6 December 2024). ISBN 9781315657622.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link)