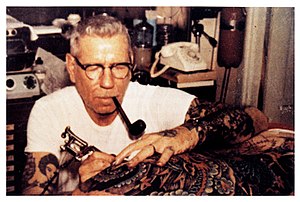

Norman Keith Collins (January 14, 1911 – June 12, 1973), known popularly as Sailor Jerry, was a prominent American tattoo artist in Hawaii who was well known for his tattoo designs.

Sailor Jerry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Norman Keith Collins January 14, 1911 Reno, Nevada, U.S. |

| Died | June 12, 1973 (aged 62) Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Other names | Norman K. Collins, Norman "Sailor Jerry" Collins, NKC, Sailor Jerry, SJ |

| Occupation(s) | Tattoo artist, sailor, musician |

| Spouse | Louise Collins[1] |

Early life

editNorman Keith Collins was born on January 14, 1911, in Reno but grew up in Northern California. As a teenager he hopped freight trains across the country[2] and learned tattooing from a man named "Big Mike" from Palmer, Alaska, originally using the hand-poke method. In the late 1920s he met Gib "Tatts" Thomas from Chicago who taught him how to use a tattoo machine.[3] He practiced on drunks brought in from Skid Row.[4]

At age 19, Collins enlisted in the United States Navy. During his subsequent travels at sea, he was exposed to the art and imagery of Southeast Asia.

Career

editSailor Jerry made significant contributions to the art of tattooing. He expanded the array of tattoo ink colors available by developing his own pigments. He created custom needle formations that embedded pigment with much less trauma to the skin. He became one of the first artists to utilize single-use needles. His tattoo studio was one of the first to use an autoclave to sterilize equipment.[5]

Collins's last studio was at 1033 Smith Street in Honolulu's Chinatown. At the time, it was the only place on the island where tattoo studios were located. His studio became China Sea Tattoo after his death. His earlier studios were at 434 South State Street, 150 North Hotel Street and 13 South Hotel Street.

Collins developed tattoo designs with inspiration from sailor tattoos and Japanese tattoo imagery.[3] He reworked 1920s–1930s designs with influences from Japanese artists, creating American traditional designs that appealed to a wider audience.[6] Among Sailor Jerry's most well-known designs were:

- Bottles of booze

- Snakes

- Wildcats

- The infamous "Aloha" monkey

- Eagles, falcons and other birds of prey

- Swallows

- Motor heads and pistons

- Nautical stars

- Classically styled scroll banners

- Knives, guns and other weapons

- Dice

- Anchors

- Hawaii themes

- Pin-up girls

In the 1950s he worked as a licensed skipper of a tour ship.[7]

Legacy

editSailor Jerry's influence on the art of modern tattooing is widely recognized.[8][9]

A documentary film about his life, Hori Smoku Sailor Jerry, was released in 2008.[10][11]

Since 2015, an annual independently-produced event has taken place in June, called the Sailor Jerry Festival, to honor Collins' legacy in Honolulu's Chinatown.[12] The event has included live music, art shows, movie screenings, a fashion show, neighborhood tours, and tattoos available at area shops.[13][14] A portion of the proceeds from the event is donated every year to the Collins family.

Image rights

editSailor Jerry wanted at least one of three protégés/friends – Ed Hardy, Mike Malone, or Zeke Owen – to take over his shop (or else burn it) when he died.[15][16] Malone purchased the shop and its contents.[16]

In 1999, Ed Hardy and Mike Malone partnered with Steven Grasse from the Philadelphia-based creative agency, Quaker City Mercantile, to establish Sailor Jerry Ltd.[17][18] The limited company, which owns the commercial rights to Collins' letters, art, and flash, uses his designs on clothing and items such as ash trays, sneakers, playing cards, churchkeys and shot glasses.

Sailor Jerry Ltd. produced a 92-proof spiced "navy rum" featuring a Sailor Jerry hula girl on the label. As the bottle is emptied, additional pin-up girls designed by Sailor Jerry are visible on the inner side of the label. The rum business was purchased by William Grant & Sons in 2008.[1]

In 2019, widow Louise Collins sued William Grant & Sons for unauthorized use of the Sailor Jerry name and imagery for their rum, claiming that she was not properly paid for the naming rights and that he would not have approved of the sale of alcohol using his name.[1][19] She was paid $20,000 for his shop and its contents in 1973 but disputed whether this sale included intellectual property or personality rights.[16] The lawsuit was settled in 2020.[20]

Personal life

editCollins played the saxophone in a dance band and frequently hosted his own radio show, where he was known as "Old Ironsides".[7][21]

He was known for being stubborn.[15] He had conservative politics and disagreed with taxes.[11]

Collins died on June 12, 1973, survived by his wife Louise and four children.[22] She was his fifth wife.[15] He is buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, a military cemetery located in Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Widow of tattooist Sailor Jerry sues whisky giants William Grant for "cashing in" on her husband's legacy". The Scotsman. June 23, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Kurutz, Steve (March 14, 2004). "INK INC". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b DeMello, Margo (May 30, 2014). Inked: Tattoos and Body Art around the World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 123–125. ISBN 978-1-61069-076-8.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. ABC-CLIO. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Levy, Janey (September 1, 2008). Tattoos in Modern Society. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4042-1829-1. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Oatman-Stanford, Hunter (December 10, 2012). "Hello Sailor! The Nautical Roots of Popular Tattoos". Collectors Weekly. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Norman Keith Collins". Tattoo Archive. 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Rubin, Arnold (1988). "The Tattoo Renaissance". In Rubin, Arnold (ed.). Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body. Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles. ISBN 978-0-930741-12-9.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2000). Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Duke University Press. pp. 72–75. ISBN 978-0-8223-2467-6.

- ^ Savlov, Marc (March 14, 2008). "SXSW Film: Got Ink? 'Hori Smoku Sailor Jerry'". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Stanley, John (December 13, 2009). "DVD: 'Hori Smoku Sailer Jerry'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Erin (June 16, 2017). "Yo Ho Ho! Punks and rum are in the festival mix to celebrate Sailor Jerry in Honolulu". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. pp. T10. Retrieved August 15, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nitta-Lee, Brittney (June 8, 2016). "The Ultimate Guide to the Sailor Jerry Festival 2016". Honolulu Magazine. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Gee, Pat (June 11, 2023). "Sailor Jerry turned tattoos into art". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. pp. D3. Retrieved August 15, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Corcoran, Michael (October 21, 2016). "Celebrate 'Sailor Jerry,' who shaped future of tattooing in U.S." Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c Michael Corcoran (October 31, 2014). "STEWED, SCREWED AND TATTOOED: The Selling of Sailor Jerry". Arts+Labor. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Mays, Greg (June 6, 2015). "Meet Steven Grasse: History in a Bottle". Burn Blog. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Holmes, Julia (December 4, 2017). "The Adman's Whiskey Lab". Men's Journal. Arena Media Brands. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Macaskill, Mark (August 15, 2024). "Sailor Jerry's spirit haunts William Grant in legal action". The Times. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Brittain, Blake (September 24, 2020). "Sailor Jerry's Heirs Settle Claims Against Same-Named Rum Maker". Bloomberg Law. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Clerk, Carol (February 17, 2009). Vintage Tattoos: The Book of Old-School Skin Art. Rizzoli. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7893-1824-4.

- ^ "Norman Collins". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. June 14, 1973. Retrieved August 15, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.