Sōsaku-hanga (創作版画, "creative prints") was an art movement of woodblock printing which was conceived in early 20th-century Japan. It stressed the artist as the sole creator motivated by a desire for self-expression, and advocated principles of art that is "self-drawn" (自画 jiga), "self-carved" (自刻 jikoku) and "self-printed" (自摺 jizuri). As opposed to the parallel shin-hanga ("new prints") movement that maintained the traditional ukiyo-e collaborative system where the artist, carver, printer, and publisher engaged in division of labor.

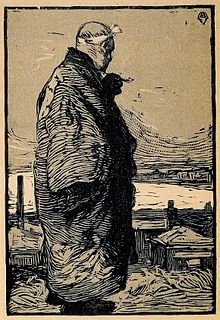

The birth of the sōsaku-hanga movement was signaled by Kanae Yamamoto's (1882–1946) small print Fisherman in 1904. Departing from the ukiyo-e collaborative system, Yamamoto made the print solely on his own: drawing, carving, and printing the image. Such principles of "self-drawn", "self-carved" and "self-printed" became the foundation of the movement, which struggled for existence in prewar Japan, and gained its momentum and flourished in postwar Japan as the genuine heir to the ukiyo-e tradition. In practice, however, the distinction of sosaku-hanga to other movements was not so distinct. For example, one of the leading artists, Kōshirō Onchi, commissioned carvers, such as Yamagishi Kazue, and printers, such as his student Jun'ichirō Sekino, to produce his work.

The 1951 São Paulo Art Biennial witnessed the success of the creative print movement. Both of the Japanese winners, Yamamoto and Kiyoshi Saitō (1907–1997) were printmakers, who outperformed Japanese paintings (nihonga), Western-style paintings (yōga), sculptures and avant-garde. Other sōsaku-hanga artists such as Kōshirō Onchi (1891–1955), Un'ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997), Sadao Watanabe (1913–1996) and Maki Haku (1924–2000) are also well known in the West.

Origins and early years

editThe creative print movement was one of the many manifestations of the rise of the individual after decades of modernization. In both artistic and literary circles, there emerged at the turn of the century expressions of the "self". In 1910, Kōtarō Takamura's (1883–1956) "A Green Sun" encouraged artists' individual expression: "I desire absolute freedom of art. Consequently I recognize the limitless authority of individuality of the artist ... Even if two or three artists should paint a "green sun", I would never criticize them for I myself may see a green sun". In 1912, in "Bunten and the Creative Arts" (Bunten to Geijutsu), Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916) states that "art begins with the expression of the self and ends with the expression of the self". These two essays marked the beginning of the intellectual discussion of the "self", which immediately found echo in the art scene. 1910 witnessed the first publication of a monthly magazine called White Birch (Shirakaba), the most important magazine shaping the thought of the Taishō period. Aspiring young artists organized its first exhibition in the same year. Shirakaba also sponsored exhibitions of Western art.

In its formative years, the sōsaku-hanga movement, like many others such as the shin-hanga, futurism and proletarian art movements, struggled to survive, experiment and find a voice in an art scene dominated by those mainstream arts that were well received by the Bunten (Japan Art Academy). Hanga in general (including shin-hanga) did not achieve the status of Western oil paintings (yōga) in Japan. Hanga was considered a craft that was inferior to paintings and sculptures. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints had always been considered as mere reproductions for mass commercial consumption, as opposed to the European view of ukiyo-e as art, during the climax of Japonisme. It was impossible for sōsaku-hanga artists to make a living by just doing creative prints. Many of the later renowned sōsaku-hanga artists, such as Kōshirō Onchi (also known as the father of the creative print movement), were book illustrators and wood carvers. It was not until 1927 that hanga was accepted by the Teiten (the former Bunten). In 1935, extracurricular classes on hanga were finally permitted.

Wartime

editThe wartime years from 1939 to 1945 was a time of metamorphosis for the creative print movement. The First Thursday Society, which was crucial to the postwar revival of Japanese prints, was formed in 1939 through the groups of people who gathered once a month in the house of Kōshirō Onchi in Tokyo to discuss subjects of woodblock prints. First initial members included Gen Yamaguchi (1896–1976) and Jun'ichirō Sekino (1914–1988). American connoisseurs Ernst Hacker, William Hartnett and Oliver Statler also attended and helped revive Western interest in Japanese prints. The First Thursday Collection (Ichimoku-shū), a collection of prints by members to circulate among each other, was produced in 1944. The group provided comradeship and a venue for artistic exchange and nourishment during the difficult war years when resources were scarce and censorship severe.

Postwar creative print movement

editThe rebirth of the Japanese print coincided with the rebirth of Japan after World War II. During the islands' occupation, American soldiers and their wives bought and collected Japanese prints as souvenirs. It can be said that Japanese prints became one of the components of postwar economic reconstruction. With the aim of promoting "democratic art", American patronage shifted from the more traditional shin-hanga to the modern-leaning sōsaku-hanga. Abstract art had been banned by the military government during wartime, but postwar, artists such as Kōshirō Onchi turned completely to abstract art. By 1950 abstraction was the primary mode of the creative print movement, and Japanese prints were perceived as a genuine blending of East and West. The 1951 São Paulo Art Biennial was Japan’s first postwar submission to an international exhibition. Notable artists such as Shikō Munakata (1903–1975) and Naoko Matsubara (b. 1937) worked in the folk art tradition (mingei), and held solo shows in the United States.

Contemporary Japanese prints

editContemporary Japanese prints have a rich diversity in subject matter and style. Tetsuya Noda (b. 1940) employs photography and produces everyday qualities in his prints in the form of photographic diaries. Artists such as Maki Haku (1924–2000) and Shinoda Toko (1913–2021) synthesize calligraphy and abstract expression and produce strikingly beautiful and serene images. Sadao Watanabe worked in the mingei (folk art) tradition, synthesizing Buddhist figure portrayal and Western Christianity in his unique Biblical prints.

From the 1960s onwards, the line between fine art and commercial media became blurred. Pop and conceptual artists work with professional technicians, and possibilities for innovation are endless.

Notable sōsaku hanga artists

edit- Okiie Hashimoto

- Azechi Umetarō

- Eiichi Kotozuka

- Un'ichi Hiratsuka

- Itow Takumi

- Kitaoka Fumio

- Koizumi Kishio

- Yasuhide Kobashi

- Sakuichi Fukazawa

- Masao Maeda

- Toshirō Maeda

- Senpan Maekawa

- Maki Haku

- Matsubara Naoko

- Yoshitoshi Mori

- Shikō Munakata

- Hajime Namiki

- Tetsuya Noda

- Gihachiro Okuyama

- Kōshirō Onchi

- Saitō Kiyoshi

- Kihei Sasajima

- Sekino Jun'ichirō

- Takumi Shinagawa

- Toko Shinoda

- Hiroyuki Tajima

- Tomikichirō Tokuriki

- Sadao Watanabe

- Gen Yamaguchi

- Kanae Yamamoto

- Hodaka Yoshida

- Tōshi Yoshida

- Ansei Uchima

- Suwa Kanenori

- Fujimori Shizuo

- Kiichi Okamoto

- Tadashige Ono

See also

editFurther reading

edit- Ajioka, Chiaki, Kuwahara, Noriko and Nishiyama, Junko. Hanga: Japanese creative prints. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, c2000. ISBN 0-7347-6313-1

- Blakemore, Frances. Who’s Who in Modern Japanese Prints. New York: Weatherhill, 1975.

- Fujikake, Shizuya. Japanese Woodblock Prints. Tokyo: Japan Travel Bureau, 1957.

- Jenkins, Donald, and Gilkey, Gordon, and Klemperer, Louise. Images of a Changing World - Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century, 1983. Portland Art Museum, Oregon.

- Kawakita, Michiaki. Contemporary Japanese Prints. Tokyo and Palo Alto: Kodansha, 1967.

- Keyes, Roger. Break with the Past: The Japanese Creative Print Movement, 1910-1960. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1988.

- Michener, James. The Modern Japanese Print: An Appreciation. Rutland & Tokyo: Tuttle, 1968.

- Milone, Marco. La xilografia giapponese moderno-contemporanea, Edizioni Clandestine, 2023, ISBN 88-6596-746-3

- Petit G. and Arboleda A. Evolving Techniques in Japanese Woodblock Prints. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1977.

- Statler, Oliver. Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Rutland & Tokyo: Tuttle, 1956.

- Smith, Lawrence. Japanese Prints During the Allied Occupation 1945–1952: Onchi Koshiro, Ernst Hacker and the First Thursday Society. Art Media Resources, 2002. ISBN 0-7567-8527-8

- Volk, Alicia. Made in Japan: The Postwar Creative Print Movement. Milwaukee Art Museum and University of Washington Press, 2005. ISBN 0-295-98502-X