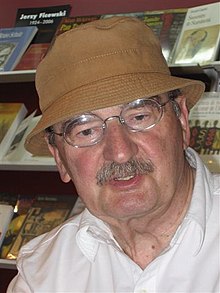

Sławomir Mrożek (29 June 1930 – 15 August 2013) was a Polish dramatist, writer and cartoonist.

Sławomir Mrożek | |

|---|---|

Warsaw, 21 May 2006 | |

| Born | 29 June 1930 Borzęcin, Poland |

| Died | 15 August 2013 (aged 83) Nice, France |

| Occupation | Dramatist, writer |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Citizenship | Polish, French |

| Notable works | Tango The Police |

| Notable awards | Kościelski Award (1962) Austrian State Prize for European Literature (1972) Legion of Honour (2003)[1] Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (2013)[2] |

| Signature | |

Mrożek joined the Polish United Workers' Party during the reign of Stalinism in the People's Republic of Poland, and made a living as a political journalist. He began writing plays in the late 1950s. His theatrical works belong to the genre of absurdist fiction, intended to shock the audience with non-realistic elements, political and historic references, distortion, and parody.[3]

In 1963 he emigrated to Italy and France, then further to Mexico. In 1996 he returned to Poland and settled in Kraków. In 2008 he moved back to France.[4] He died in Nice at the age of 83.[5]

Postwar period

editMrożek's family lived in Kraków during World War II. He finished high school in 1949 and in 1950 debuted as a political hack-writer on Przekrój. In 1952 he moved into the government-run Writer's House (ZLP headquarters with the restricted canteen).[6] In 1953, during the Stalinist terror in postwar Poland, Mrożek was one of several signatories of an open letter from ZLP to Polish authorities supporting the persecution of Polish religious leaders imprisoned by the Ministry of Public Security. He participated in the defamation of Catholic priests from Kraków, three of whom were condemned to death by the Communist government in February 1953 after being groundlessly accused of treason (see the Stalinist show trial of the Kraków Curia). Their death sentences were not enforced, although Father Józef Fudali died in unexplained circumstances while in prison.[7][8][9][10][11][12] Mrożek wrote a full-page article for the leading newspaper in support of the verdict, entitled "Zbrodnia główna i inne" (The Capital Crime and Others),[13] comparing death-row priests to degenerate SS-men and Ku-Klux-Klan killers.[14] He married Maria Obremba living in Katowice and relocated to Warsaw in 1959. In 1963 Mrożek travelled to Italy with his wife and decided to defect together. After five years in Italy, he moved to France and in 1978 received French citizenship.[6]

After his defection, Mrożek turned critical of the Polish communist regime. Later, from the safety of his residence in France, he also protested publicly against the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.[15] Long after the collapse of the Soviet empire, he commented thus on his fascination with Communism:

Being twenty years old, I was ready to accept any ideological proposition without looking a gift-horse in the mouth – as long as it was revolutionary. [...] I was lucky not to be born German say in 1913. I would have been a Hitlerite because the recruitment method was the same.[16]

His first wife, Maria Obremba, died in 1969. In 1987 he married Susana Osorio-Mrozek, a Mexican woman. In 1996, he relocated back to Poland and settled in Kraków. He had a stroke in 2002, resulting in aphasia, which took several years to cure. He left Poland again in 2008, and moved to Nice in southern France. Sławomir Mrożek died in Nice on 15 August 2013. Not a religious person by any means, on 17 September 2013 he was buried at the St. Peter and Paul Church in Kraków. The funeral mass was conducted by the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz.[15]

Literary career

editMrożek's first play, The Police, was published in 1958. His first full-length play, Tango (1965) written about totalitarianism in the style of Theatre of the Absurd, made him, according to Krystyna Dąbrowska, one of the most recognizable Polish contemporary dramatists in the world.[4] It became also Mrożek's most successful play, according to Britannica, produced in many Western countries.[3] In 1975 his second popular play Emigranci (The Émigrés),[17] a bitter and ironic portrait of two Polish emigrants in Paris, was produced by director Andrzej Wajda at the Teatr Stary in Kraków.[18]

Mrożek traveled to France, England, Italy, Yugoslavia and other European countries.[19] After the military crackdown of 1981 Mrożek wrote the only play he ever regretted writing, called Alfa, about the imprisoned Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa who became President of Poland after the collapse of the Soviet empire. See also "fałszywka".[20] After the introduction of martial law in Poland, productions of Alfa were banned, along with two of Mrożek's other plays, The Ambassador and Vatzlav.[16] The later play, in Gdańsk, in the city known as the birth and home to Solidarity (Polish trade union) and its leader Lech Walesa, Theater Wybrzeze courageously premiered "Vatzlav". These were the times that the country had food shortages, curfews and a police hour. Many actors were interned including actor Jerzy Kiszkis who played the title role of "Vatzlav". A Gdańsk born actress, activist and Solidarity Solidarność (Solidarity)supporter Beata Pozniak, was asked to play Justine, a character that symbolized justice. Censorship in theaters were enforced. It was noted that in this 1982 Gdańsk production, the censor stopped Mrozek's play not allowing many gestures made by actors on stage, including Justine's father wearing a beard, because he reminded her too much of Karl Marx.[21]

List of works

editList of plays by Mrożek (below) is based on Małgorzata Sugiera's "Dramaturgia Sławomira Mrożka" (Dramatic works of Sławomir Mrożek):[citation needed]

- Professor / The professor[22]

- Policja / The Police, "Dialog" 1958, nr 6

- Męczeństwo Piotra Oheya / The Martyrdom of Peter Ohey, "Dialog" 1959, nr 6

- Indyk / The Turkey, "Dialog" 1960, nr 10

- Na pełnym morzu / At Sea, "Dialog" 1961, nr 2

- Karol / Charlie, "Dialog" 1961, nr 3

- Strip-tease, "Dialog" 1961, nr 6

- Zabawa / The Party, "Dialog" 1962, nr 10

- Kynolog w rozterce / Dilemmas of a dog breeder, "Dialog" 1962, nr 11

- Czarowna noc / The magical night, "Dialog" 1963, nr 2

- Śmierć porucznika / The death of the lieutenant, "Dialog" 1963, nr 5

- Der Hirsch, trans. Ludwik Zimmerer (in:) STÜCKE I, Berlin (West), 1965 (no Polish version)

- Tango, "Dialog" 1965, nr 11

- Racket baby, trans. Ludwik Zimmerer (in:) STÜCKE I, Berlin (West), 1965 (no Polish version)

- Poczwórka / The quarter, "Dialog" 1967, nr 1

- Dom na granicy / The house on the border, "Dialog" 1967, nr 1

- Testarium, "Dialog" 1967, nr 11

- Drugie danie / The main course, "Dialog" 1968, nr 5

- Szczęśliwe wydarzenie / The fortunate event, "Kultura" 1971, nr 5

- Rzeźnia / The slaughterhouse, "Kultura" 1971, nr 5

- Emigranci / The Émigrés, "Dialog" 1974, nr 8

- Garbus / The Hunchback, "Dialog" 1975, nr 9

- Serenada / The Serenade, "Dialog" 1977, nr 2

- Lis filozof / The philosopher fox, "Dialog" 1977, nr 3

- Polowanie na lisa / Fox hunting, "Dialog" 1977, nr 5

- Krawiec / The Tailor (written in 1964) "Dialog" 1977, nr 11

- Lis aspirant / The trainee fox, "Dialog" 1978, nr 7

- Pieszo / On foot, "Dialog" 1980, nr 8

- Vatzlav (written in 1968), published by the Instytut Literacki (Literary Institute in Paris)

- Ambassador / The Ambassador, Paris 1982

- Letni dzień / A summer day, "Dialog" 1983, nr 6

- Alfa / Alpha, Paryz, 1984

- Kontrakt / The contract, "Dialog" 1986, nr 1

- Portret / The portrait, "Dialog" 1987, nr 9

- Wdowy / Widows (written in 1992)

- Milość na Krymie / Love in the Crimea, "Dialog" 1993, nr 12

- Wielebni / The reverends, "Dialog" 2000, nr 11

- Piękny widok / A beautiful sight, "Dialog" 2000, nr 5

English translations

edit- Tango. New York: Grove Press, 1968.

- The Ugupu Bird (selected stories from: Wesele w Atomicach, Deszcz and an excerpt from Ucieczka na południe). London: Macdonald & Co., 1968.

- Striptease, Repeat Performance, and The Prophets. New York: Grove Press, 1972.

- Vatzlav. London: Cape, 1972.

- The Elephant (Słoń). Westport: Greenwood Press, 1972.

Notes

edit- ^ "Le dramaturge et écrivain Slawomir Mrozek est décédé". Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ "Prezydent wręczył odznaczenia w Kamieniu Śląskim". Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Sławomir Mrożek, from theEncyclopædia Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b Krystyna Dąbrowska, Sławomir Mrożek. Archived 29 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine Culture.pl, September 2009.

- ^ Staff writer (15 August 2013). "Sławomir Mrożek nie żyje". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Sławomir Mrożek trail". Malopolska Regional Operational Programme ERDF. Literacka Małopolska. 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

Legend with collection of links. See section: "Nowa Huta" (quote): Sławomir Mrożek's debut was connected with Nowa Huta – the "front page" reportage Młode Miasto [Young City] devoted to everyday life and work of young people who were building the communist conglomerate plant and housing estate (Przekrój, issue no. 272, 22nd of July 1950).

- ^ "Ks. Józef Fudali (1915–1955), kapłan Archidiecezji Krakowskiej". Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Institute of National Remembrance. Retrieved 11 October 2011. - ^ David Dastych, "Devil's Choice. High-ranking Communist Agents in the Polish Catholic Church." Archived 25 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine Canada Free Press (CFP), 10 January 2007.

- ^ Wojciech Czuchnowski Blizna. Proces kurii krakowskiej 1953, Kraków 2003.

- ^ Dr Stanisław Krajski, "Zabić księży." Archived 14 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Katolicka Gazeta Internetowa, 2001-12-01.

- ^ Damian Nogajski, WINY MAŁE I DUŻE – CZYLI KTO JEST PASZKWILANTEM. Archived 29 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Polskiejutro.com, No. 227; 11 September 2006.

- ^ Katarzyna Kubisiowska (interview with Sławomir Mrożek), "Wiem, jak się umiera,"[dead link]Rzeczpospolita, archiwum.

- ^ Sławomir Mrożek. ""Zbrodnia główna i inne" (The Capital Crime and Others)". Full text of article by Mrożek in Polish. Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Proces Kurii Krakowskiej". Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Institute of National Remembrance (IPN). Retrieved 1 November 2011. - ^ a b Monika Scislowska (17 September 2013), Polish playwright Slawomir Mrozek buried in Krakow. Archived 6 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine Associated Press.

- ^ a b Dąbrowska, Krystyna. "Sławomir Mrożek". Adam Mickiewicz Institute Culture.pl. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

Source: Sławomir Mrożek, Baltazar: autobiografia (in Polish), Publisher: Noir sur Blanc, 2006. OCLC 469692369. Page 149.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ August Grodzicki, "Bardzo polska tragikomedia." Życie Warszawy nr 5; 7 Jan 1976

- ^ Sławomir Mrożek literary evening in the Polish Institute, 27 February 2007, Lengyel Intézet, Budapest.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Sławomir Mrożek". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014.

- ^ Małgorzata I. Niemczyńska (26 March 2013). "Lata 80. Sławomira Mrożka. Depresja, ślub, wyjazd i sztuka o Wałęsie, której później się wstydził". Kultura (in Polish). Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Poźniak, Beata (28 March 2016). "World Theatre Day".

- ^ Source: Jerzy Afanasjew, Sezon kolorowych chmur. Z życia Gdańskich teatrzyków 1954–1964 (The season of colorful clouds – from the life of Gdańsk's small theatres 1954–1964), Gdynia 1968.

Further reading

edit- Alek Pohl (1972) Zurück zur Form. Strukturanalysen zu Slawomir Mrozek. Berlin: Henssel ISBN 3-87329-064-2

- Halina Stephan (1997) Transcending the Absurd: drama and prose of Slawomir Mrozek. (Studies in Slavic Literature and Poetics; 28). Amsterdam: Rodopi ISBN 90-420-0113-5

External links

edit- ["Mrozek's Vatzlav Censored on Stage" Theatre in Gdańsk [1]

- Sławomir Mrozek at culture.pl

- "Interview with Mrozek". Archived from the original on 23 July 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2005.

- Petri Liukkonen. "Sławomir Mrożek". Books and Writers.

- On Sławomir Mrożek – Playwright's Tango

- Review: Sławomir Mrożek's "Diary. 1962–1989"