In Estonia, the population of ethnic Russians (Russian: Русские Эстонии, romanized: Russkiye Estonii, Estonian: Eesti venelased) is estimated at 296,268, most of whom live in the capital city Tallinn and other urban areas of Harju and Ida-Viru counties. While a small settlement of Russian Old Believers on the coast of Lake Peipus has an over 300-year long history, the large majority of the ethnic Russian population in the country originates from the immigration from Russia and other parts of the former USSR during the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation of Estonia.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 296,268 (est.) (21.5% of total population) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Harju County, Ida-Viru County | |

| Languages | |

| Russian and Estonian | |

| Religion | |

| Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate |

Early contacts

editThe modern Estonian-language word for Russians vene(lane) is probably related to an old Germanic word veneð referring to the Wends, speakers of a Slavic language who lived on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea during the Middle Ages.[1][2]

The troops of prince Yaroslav the Wise of Kievan Rus' defeated Estonian Chuds in ca. 1030 and established a fort of Yuryev (in modern-day Tartu),[3] which may have survived there until ca. 1061, when the fort's defenders were defeated and driven out by the tribe of Sosols.[4][5]

Due to close trade links with the Novgorod and Pskov republics, small communities of Orthodox merchants and craftsmen from these neighboring states sometimes remained in the Estonian towns of medieval Terra Mariana for extended periods of time. Between 1558 and 1582, Ivan the Terrible of Russia (Tsardom of Russia) captured large parts of mainland Estonia, but eventually his troops were driven out by Swedish and Lithuanian-Polish armies.

17th century to independent Estonia

editThe beginning of continuous Russian settlement in what is now Estonia dates back to the late 17th century when several thousand Eastern Orthodox Old Believers, escaping religious persecution in Russia, settled in areas then a part of the Swedish empire near the western coast of Lake Peipus.[6]

In the 18th century, after the Imperial Russian conquest of the northern Baltic region, including Estonia, from Sweden in the Great Northern War (1700–1721),[7] a second period of immigration from Russia followed. Although under the new rule, power in the region remained primarily in the hands of the local Baltic German nobility, but a limited number of administrative jobs was gradually taken over by Russians, who settled in Reval (Tallinn) and other major towns.

A relatively larger number of ethnic Russian workers settled in Tallinn and Narva during the period of rapid industrial development at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. After World War I, the share of ethnic Russians in the population within the boundaries of newly independent Estonia was 7.3%.[8] About half of these were indigenous ethnic Russians living in the Petseri (Pechory) district and east of Narva river ("Estonian Ingria"), in the two areas which had been added to Estonian territory according to the 1920 Peace Treaty of Tartu, but were transferred to the Russian SFSR in 1944.

In the aftermath of World War I Estonia became an independent state where ethnic Russians established Cultural Self-Governments according to the 1925 Estonian Law on Cultural Autonomy.[9] The state was tolerant of the Russian Orthodox Church and became a home to many Russian émigrés after the Russian Revolution in 1917.[10]

World War II and Soviet Estonia

editAfter the Occupation and annexation of the Baltic states by the Soviet Union in 1940,[11][12] repression of both ethnic Estonians and ethnic Russians followed. According to Sergei Isakov, almost all societies, newspapers, organizations of ethnic Russians in Estonia were closed in 1940 and their activists persecuted.[13] The country remained annexed to the Soviet Union until 1991, except for the period of Nazi German occupation between 1941 and 1944. In the course of population transfers, thousands of Estonian citizens were deported to the interior parts of Russia (mostly Siberia), and huge numbers of Russian-speaking Soviet citizens were encouraged to settle in Estonia. During the Soviet era, the Russian population in Estonia grew from about 23,000 people in 1945 to 475,000 in 1991, and other Russian-speaking population to 551,000, constituting 35% of the total population at its peak.[14]

In 1939 ethnic Russians had comprised 8% of the population; however, following the annexation of about 2,000 km2 (772 sq mi) of land by the Russian SFSR in January 1945, including Ivangorod (then the eastern suburb of Narva) and the Petseri County, Estonia lost most of its inter-war ethnic Russian population. Of the estimated 20,000 Russians remaining in Estonia, the majority belonged to the historical community of Old Believers.[15]

Most of the present-day Russians in Estonia are recent migrants and their descendants who settled in during the Soviet era between 1945 and 1991. After the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in 1940. The Stalinist authorities carried out repressions against many prominent ethnic Russians activists and White emigres in Estonia.[16] Many Russians were arrested and executed by different Soviet war tribunals in 1940–1941.[17] After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, the Baltic States quickly fell under German control. Many Russians, especially Communist party members who had arrived in the area with the initial occupation and annexation, retreated; those who fell into the German hands were treated harshly, many were executed.[citation needed]

After the war, Narva's inhabitants were for the most part not permitted to return and were replaced by refugees and workers administratively mobilized mostly among Russians, as well as other parts of the Soviet Union.[18] By 1989, ethnic Russians made up 30.3% of the population in Estonia.[19]

During the Singing Revolution, the Intermovement, International Movement of the Workers of the ESSR, organised the local Russian resistance to the independence movement and purported to represent the ethnic Russians and other Russophones in Estonia.[20]

Post-Soviet Estonia (1991–present)

editToday most Russians live in Tallinn and the major northeastern cities of Narva, Kohtla-Järve, Jõhvi, and Sillamäe. The rural areas are populated almost entirely by ethnic Estonians, except for the coast of Lake Peipus, which has a long history of Old Believers communities. In 2011, University of Tartu sociology professor Marju Lauristin found that 21% were successfully integrated, 28% showed partial integration, and 51% were unintegrated or little integrated.[21]

There are efforts by the Estonian government to improve its tie with the Russian community with former Prime Minister Jüri Ratas learning Russian to better communicate with them.[22] Former President Kersti Kaljulaid is also considered to be a defender of the interests of the Russian-speaking minority, having previously moved to Narva in order to "better understand the people and their problems".[23] The younger generation is better integrated with the rest of the country such as joining the military via conscription and improving their Estonian language skills.[22]

Citizenship

editThe restored republic recognised citizenship only for the pre-occupation citizens or descendants from such (including the long-term Russian settlers from earlier influxes, such as Lake Peipus coast and the 10,000 residents of the Petseri County)[24], rather than to grant Estonian nationality to all Estonian-resident Soviet citizens. The Citizenship Act provides the following requirements for naturalisation of those people who had arrived in the country after 1940,[25] the majority of whom were ethnic Russians: knowledge of the Estonian language, Constitution and a pledge of loyalty to Estonia.[26] The government offers free preparation courses for the examination on the Constitution and the Citizenship Act, and reimburses up to 380 euros for language studies.[27]

Under the law, residents without citizenship may not elect the Riigikogu (the national parliament) nor the European Parliament, but are eligible to vote in the municipal elections.[28] As of 2 July 2010, 84.1% of Estonian residents are Estonian citizens, 8.6% are citizens of other countries (mainly Russia) and 7.3% are "persons with undetermined citizenship".[29]

Between 1992 and 2007 about 147,000 people acquired Estonian or Russian citizenship, or left the country, bringing the proportion of stateless residents from 32% down to about 8 percent.[28] According to Amnesty International's 2015 report, approximately 6.8% of Estonia's population are not citizens of the country.[30]

In late 2014 an amendment to the law was proposed that would give Estonian citizenship to children of non-citizen parents who have resided in Estonia for at least five years.[31]

Language requirements

editThe perceived difficulty of the language tests became a point of international contention, as the government of the Russian Federation and a number of human rights organizations[specify] objected on the grounds that they made it hard for many Russians who had not learned the language to gain the citizenship in the short term.[citation needed] As a result, the tests were altered somewhat, due to which the number of stateless persons steadily decreased. According to Estonian officials, in 1992, 32% of residents lacked any form of citizenship. In May 2009, the Population register reported that 7.6% of residents have undefined citizenship and 8.4% have foreign citizenship, mostly Russian.[32] As the Russian Federation was recognized as the successor state to the Soviet Union, all former USSR citizens qualified for natural-born citizenship of Russia, available upon request, as provided by the law "On the RSFSR Citizenship" in force up to the end of 2000.[33]

Socioeconomic status

editAccording to a 2016 report by the European Centre for Minority Issues, the Russian-speaking population in Estonia faced significant challenges in the labor market and education after the post-Soviet transition, which fostered a persistent perception of inequality among minority groups. Today, health conditions and access to healthcare are similar for both majority and minority populations. However, accumulated disadvantages affect marginalized Russian-speaking communities, who experience higher rates of extreme poverty, incarceration, homelessness, drug abuse, and HIV/AIDS. These issues contribute to social exclusion and may hinder the right to health for ethnic Russians and other minorities. Additionally, the reduced use of Russian in healthcare services has emerged as a new challenge, given Estonia's demographic composition.[34]

Estonian statistics show that ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers are disproportionately represented in a number of areas, including:

- 83% of persons registered as HIV-positive

- 70-85% of prostitutes

- nearly 60% of prison inmates

- 98% of injecting drug users

- 66.4% of the homeless population in Tallinn

Politics

editHistorically, the Estonian Centre Party has been the most popular party among Russian-speaking citizens. In 2012, it was supported by up to 75% of ethnic non-Estonians.[35]

In 2021, some pundits advanced as speculation that since 2019, Conservative People's Party of Estonia support grew in the Russian community (notably in Ida-Viru County which has a majority of Russians), despite the party's Estonian nationalism and oftentimes anti-Russian rhetoric and positions. This was speculated by them to be attributable to the party opposition to European Union federalism and the softening of the rhetoric of the party at the time on Russia, and to its then coalition with the Centre Party.[36][37] However, despite these claims, the Conservative People's party underperformed in Ida-Viru County during the 2023 Estonian parliamentary election, with only 8.4% of the votes in that county, their lowest result. In that county, the leftist and Russian minority-oriented Estonian United Left Party performed a breakthrough during this election and obtained 14.9% of the votes. This party also performed better in Tallinn, where a significant Russian minority live, than in most other parts of Estonia.[38][39]

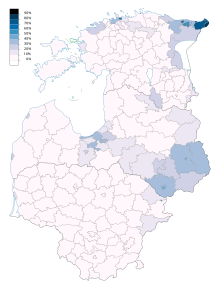

By county

edit| County | Russians | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Ida-Viru | 92 090 | 69.6% |

| Harju | 167 544 | 25.9% |

| Tartu | 15 059 | 9.1% |

| Valga | 3 252 | 11.6% |

| Lääne-Viru | 4 951 | 8.3% |

| Pärnu | 5 331 | 6% |

| Lääne | 1 445 | 7% |

| Jõgeva | 1 728 | 6.3% |

| Rapla | 1 051 | 3% |

| Põlva | 776 | 3.2% |

| Võru | 1 105 | 3.2% |

| Viljandi | 1 046 | 2.3% |

| Järva | 655 | 2.1% |

| Saare | 190 | 0.6% |

| Hiiu | 45 | 0.5% |

| Total | 296 268 | 21.5%[40] |

Notable Russians from Estonia

edit- Wilhelm Küchelbecker (1797–1846), Russian patriotic poet and Decembrist (1825) revolutionary; raised in Estonia.

- Leonid Kulik (1883–1942), Russian mineralogist, led the (1927) first Soviet expedition to investigate the Tunguska event; born in Tartu.

- Igor Severyanin (Igor Lotaryov, 1887–1941), poet; lived, married, and died in Estonia.

- Nikolai Vekšin (1887–1951), sailor, helmsman of the bronze medal winning Estonian 6 Metre boat at 1928 Amsterdam Olympic Games.

- Boris Nartsissov (1906–1982), Russian émigré poet; raised and educated in Estonia.

- Nikolai Stepulov (1913–1968), won silver medal in boxing, lightweight class at 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

- Alexy II of Moscow (Aleksei Rüdiger, 1929–2008), former Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church; born and raised in Estonia.

- Svetlana Tširkova-Lozovaja (b. 1945), former fencer, representing USSR, won Olympic gold in team foil twice (1968, 1972); lives in Estonia since early age.

- Mikhail Veller (b. 1948), Russian writer; works in Tallinn.

- Marina Kaljurand (née Rajevskaja, b. 1962), Estonian politician, Member of the European Parliament, former foreign minister.

- Anna Levandi (née Kondrashova, b. 1965), former figure skater, representing USSR, won silver at 1984 World Championships; lives in Tallinn.

- Valery Karpin (b. 1969), Russian football manager and former player, since 2021 manager of the Russia national team; born in Narva.

- Anton Vaino (b. 1972), chief of staff of the executive office of the President of Russia; born in Tallinn.

- Sergei Hohlov-Simson (b. 1972), Estonian former football player, played for Estonia national football team from 1992 to 2004.

- Kristina Kallas (b. 1976), Estonian politician, leader of the Estonia 200 political party since its foundation in 2018.

- Aleksandr Dmitrijev (b. 1982), Estonian football player with 107 international caps for Estonia.

- Tatjana Mihhailova-Saar (b. 1983), represented Estonia in the Eurovision Song Contest 2014; family moved to Estonia at 2 months.

- Konstantin Vassiljev (b. 1984), Estonian football player with 158 international caps (national record) for Estonia.

- Jevgeni Ossinovski (b. 1986), Estonian politician and former leader of the Estonian Social Democratic Party.

- Leo Komarov (Leonid Komarov, b. 1987), ice hockey player, representing Finland, 2011 World Champion and 2022 Winter Olympics gold medallist; born in Narva.

- Valentina Golubenko (b. 1990), chess Grandmaster, representing Croatia, world champion in girls' U18 category in 2008; lives in Estonia since early age.

- Elina Nechayeva (b. 1991), soprano, represented Estonia in the Eurovision Song Contest 2018.

- Alika Milova (b. 2002), singer, represented Estonia in the Eurovision Song Contest 2023.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Campbell, Lyle (2004). Historical Linguistics. MIT Press. p. 418. ISBN 0-262-53267-0.

- ^ Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past. Central European University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9789639116429.

- ^ Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 33, 59, 60. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (13 January 2004). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810865716.

- ^ Mäesalu, Ain (2012). "Could Kedipiv in East-Slavonic Chronicles be Keava hill fort?" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Archaeology. 1 (16supplser): 199. doi:10.3176/arch.2012.supv1.11. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe. ABC-CLIO. p. 65. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.

- ^ Smith, David James (2005). The Baltic States and Their Region. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1666-8.

- ^ "EESTI - ERINEVATE RAHVUSTE ESINDAJATE KODU" (in Estonian). miksike.ee.

- ^ Suksi, Markku (198). Autonomy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 253. ISBN 9041105638.

- ^ Kishkovsky, Sophia (6 December 2008). "Patriarch Aleksy II". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR. Leiden – Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-411-2177-3.

- ^ Chernichenko, S. V. (August 2004). "Об "оккупации" Прибалтики и нарушении прав русскоязычного населения" (in Russian). Международная жизнь». Archived from the original on 27 August 2009.

- ^ Isakov, S. G. (2005). Очерки истории русской культуры в Эстонии, Изд. : Aleksandra (in Russian). Tallinn. p. 21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Chinn, Jeff; Kaiser, Robert John (1996). Russians as the new minority. Westview Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-8133-2248-0.

- ^ Smith, David (2001). Estonia: independence and European integration. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-415-26728-1.

- ^ Isakov, S. G. (2005). Очерки истории русской культуры в Эстонии (in Russian). Tallinn. pp. 394–395.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2007.

- ^ Batt, Judy; Wolczuk, Kataryna (2002). Region, state, and identity in Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7146-5243-6.

- ^ "Population by Nationality". Estonia.eu.

- ^ Bunce, Valerie; Watts, Steven (2005). "Managing Diversity and Sustaining Democracy: Ethnofederal versus Unitary States in the Postcommunist World". In Philip G. Roeder, Donald Rothchild (ed.). Sustainable peace: power and democracy after civil wars. Cornell University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0801489741.

- ^ Koort, Katja (July 2014). "The Russians of Estonia: Twenty Years After". World Affairs. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Mardiste, Alistair Scrutton (24 February 2017). "Wary of divided loyalties, a Baltic state reaches out to its Russians". Reuters.

- ^ "A Controversial Visit: President of Estonia Meets with Putin at the Kremlin". 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Estonian passport holders at risk". The Baltic Times. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Ludwikowski, Rett R. (1996). Constitution-making in the region of former Soviet dominance. Duke University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8223-1802-6.

- ^ "Citizenship Act of Estonia". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Government to develop activities to decrease the number of non-citizens". Archived from the original on 1 September 2009.

- ^ a b Puddington, Arch; Piano, Aili; Eiss, Camille; Roylance, Tyler (2007). "Estonia". Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7425-5897-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Citizenship". Estonia.eu. 13 July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Amnesty International Report 2014/15: The State of the World's Human Rights". amnesty.org. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "Riigikogu asub arutama kodakondsuse andmise lihtsustamist" (in Estonian). 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Estonia: Citizenship". vm.ee. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007.

- ^ Gradirovsky, Sergei. "The Policy of Immigration and Naturalization in Russia: Present State and Prospects" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- ^ "#91: Estonian Ethnic Minorities: The Right to Health and the Dangers of Social Exclusion - European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI)". www.ecmi.de. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ Keskerakond on mitte-eestlaste seas jätkuvalt populaarseim partei, Postimees, 23 September 2012

- ^ "Party ratings: Change in coalition followed by Reform, EKRE rise in support". 27 January 2021.

- ^ "ERR News broadcast: Greening of Ida-Viru County costing Center support". 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Valimised 2023". Eesti Rahvusringhääling (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Eesti Vabariik kokku" (in Estonian).

- ^ "Population by sex, ethnic nationality and County, 1 January". stat.ee. Statistics Estonia. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

Further reading

edit- "Alternative Report for the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination of United Nations" (PDF).

- "The Russian Diaspora in Latvia and Estonia: Predicting Language Outcomes" (PDF). 13 April 2023.

- "Report on Estonia". Amnesty International. 2007.

- "Linguistic minorities in Estonia: Discrimination must end". Amnesty International. 7 December 2006.

- Lucas, Edward (14 December 2006). "An excess of conscience – Estonia is right and Amnesty is wrong". The Economist.

- Rovny, Jan (2024), "Major Minority: The Estonian Russians." in Ethnic Minorities, Political Competition, and Democracy, Oxford University Press, pp. 211–240,

- Vetik, Raivo (1993). "Ethnic conflict and accommodation in post-communist Estonia". Journal of Peace Research. 30 (3): 271–280. doi:10.1177/0022343393030003003. JSTOR 424806. S2CID 111359099.

- Andersen, Erik André (1997). "The Legal Status of Russians in Estonian Privatisation Legislation 1989–1995". Europe-Asia Studies. 49 (2): 303–316. doi:10.1080/09668139708412441. JSTOR 153989.

- Park, Andrus (1994). "Ethnicity and Independence: The Case of Estonia in Comparative Perspective". Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (1): 69–87. doi:10.1080/09668139408412150. JSTOR 153031.

- Vares, Peeter; Zhurayi, Olga (1998). Estonia and Russia, Estonians and Russians: A Dialogue. 2nd ed. Tallinn: Olof Palme International Center.

- Lauristin, Marju; Heidmets, Mati (2002). The Challenge of the Russian Minority: Emerging Multicultural Democracy in Estonia. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.