Rosa Egipcíaca, also known as Rosa Maria Egipcíaca of Vera Cruz and Rosa Courana (1719 – 12 October 1771), was a formerly enslaved writer and religious mystic, who was the author of A Sagrada Teologia do Amor de Deus Luz Brilhante das Almas Peregrinas (The Sacred Theology of Love of God Brilliant Light of Pilgrim Souls) – the oldest book written by a black woman in the history of Brazil.

Early life

editEgipcíaca was born on the Costa da Mina, close to where modern-day Lagos is in Nigeria. She was born a member of the Coura people and was enslaved when she was six years old, and taken via the Atlantic slave trade to Rio de Janeiro in 1725.[1] When she arrived she was baptised at the Igreja da Candelária and given the name Rosa (or, as she is sometimes referred to, Rosa Courana – reflecting her West African cultural identity). In 1733 she was sold to Dona Ana Garcês de Morais who owned a mining camp at Inficionado in the Minas Gerais region. Egipcíaca's previous enslaver, José de Souza de Azevedo, had sexually abused her.[2] In the mining camp, as the only enslaved woman, as an escrava de ganho,[3] she was forced to provide sex for the seventy-seven enslaved men there.[4]

Religious life

editAt the age of 29, Egipcíaca began to have supernatural visions, following a period of illness that was characterised by abdominal pain – she claimed the pain was caused by demons.[5] Historian Robert Krueger associated these symptoms with venereal disease.[4] She was exorcized by a Catholic priest, Francisco Gonçalves Lopes.[2] Originally from Minho in Portugal, Lopes was known as the "scourge of demons".[6] Subsequently, they were accused of having an affair and prosecuted by the Inquisition.[2] In 1748, after release from prison, she took the name Rosa Maria Egipcíaca da Vera Cruz, in honour of Saint Mary of Egypt.[7] She began to preach to crowds about her visions. In 1749 she was accused of witchcraft by the Bishop of Mariana and whipped in Vila de Mariana as a punishment.[2] This punishment paralysed the right side of her body for the rest of her life.[1] After this Lopes purchased her and they fled to Rio de Janeiro, where Franciscan clergy believed her visions and encouraged her to follow a Christian path.[1][2] Brother Agostinho de São José became her particular advisor, and Egipcíaca was known by the Franciscan community as the "Flower of Rio" and had a reputation for being able to endure greater lengths of fasting, self-flagellation and wearing a cilice than many of them.[6]

During this period Egipcíaca learned to read and to write, becoming the first recorded person of African origin in Brazil to learn the alphabet.[2] She was inspired to learn following a vision of St Anne.[4] She composed the book A Sagrada Teologia do Amor de Deus Luz Brilhante das Almas Peregrinas (The Sacred Theology of Love of God Brilliant Light of Pilgrim Souls), which is the first book to be written by an Afro-Brazilian woman.[1][8][9]

In 1754 she founded a new religious house – Recolhimento de Nossa Senhora do Parto (The Convent of Our Lady of Childbirth).[1] It was funded by Antônio de Desterro (pt), who was the bishop of Rio de Janeiro.[6] The building was on Rua da Assembléia (pt) and many of the twenty-strong order were also black or multiracial women, as well as former prostitutes.[2] Egipcíaca led the convent and she expelled parishioners from services if they misbehaved.[6] The order developed a focus on the cult of Sts. Anna and Joachim, Jesus' grandparents, and on the Heart of St. Joseph. It soon came to focus on the person of Egipcíaca herself.[2] She combined West African religious practices with Catholic liturgy to develop a new brand of worship.[2] This included batuque dancing. In 1756 she predicted that a flood would destroy Rio.[6] It would carry the convent to Portugal, where she would then marry King Dom Sebastião.[1] She also devised a new prayer to be used with a rosary in place of the 'Hail Mary'; the prayer was called "the Rosary of Santana" and was in her honour.[10] She also performed miraculous healings.[3]

In 1762 she and Lopes were arrested and imprisoned for taking part in the cult of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. They were imprisoned in Rio for one year, and by August 1763 they appeared at the Tribunal of the Saintly Office in Lisbon. During their interrogations, Lopes accused Egipcíaca of deceiving him, while she declared that all her visions were true.[2] Questioned on five occasions, her last recorded interrogation was in June 1765 by Jeronimo Rogado Carvalho e Silva (pt).[11] Subsequently, she worked as a kitchen servant for the Inquisition.[2]

Egipcíaca died on 12 October 1771 in the kitchen of the household of the Inquisition, reportedly of natural causes.[12]

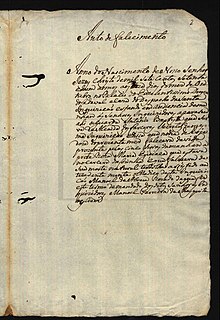

A Sagrada Teologia do Amor de Deus Luz Brilhante das Almas Peregrinas

editIn the book Egipcíaca detailed her visions, describing how she fed the infant Christ at her breast and how he combed her hair in return, that she and Jesus had swapped hearts and that she had died and been revived, among others.[1] The book was originally 290 pages long, but only six of those pages have survived.[2] The book is recognised as the oldest book written by a black woman in Brazil.[8] In Rio de Janeiro at the time of her writing, there were twenty-seven other literate women.[4]

Legacy

editThe writer Heloísa Maranhão wrote a novel inspired by Egipcíaca's life entitled Rosa Maria Egipcíaca da Vera Cruz.[13] It was published in 1997.[14] Criola, a black feminist organisation based in Rio de Janeiro, cites Egipcíaca's life as an important inspiration for their activities.[7]

Historiography

editEgipcíaca's life was overlooked until the 1993 publication by Luiz Mott of Rosa Egipcíaca: Uma santa Africana no Brasil.[6] Mott was able to trace Egipcíaca's history by using the detailed records of the Inquisition, as well as using the surviving pages of her book, and letters in the Torre de Tombo archive.[7][15] According to Mott, Egipcíaca lived the life of both a sinner and a saint, and this can be seen as a challenge to the "fixed categories the Catholic church created for women".[16] Matthias Röhrig Assunção discussed how significant it is that an enslaved African woman could become "an object of popular Catholic devotion" in Brazil.[17] Paul Christopher Johnson described her significance in terms of how she was a 'healing saint' who was a product of Afro-Brazilian culture.[3] Co-authors Monica Díaz and Rocío Quispe-Agnoli said that the pages from Egipcíaca's book and her letters "exist as some of the few remnants of African women's voices in colonial Latin American archives".[18]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g "Egipcíaca, Rosa | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade". enslaved.org. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Paul Christopher (1 June 2021). "Translating Spirits: Medical-Ritual Healing and Law in Brazil and the Broader Afro-Atlantic World". Osiris. 36: 27–45. doi:10.1086/713422. ISSN 0369-7827. S2CID 235716126.

- ^ a b c d Gardner, Jane; Wiedemann, Thomas (12 November 2013). Representing the Body of the Slave. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79171-3.

- ^ colaborador (2 July 2020). "Rosa Egipcíaca (1719–1778)". Biografias de Mulheres Africanas (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Mott, Luiz (2016). "Egipcíaca, Rosa". Oxford African American Studies Center. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.73870. ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Henery, Celeste (5 April 2021). "Excavating the History of Afro-Brazilian Women". AAIHS. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b Martins, Ana Margarida (2019). "Teresa Margarida da Silva Orta (1711–1793): A Minor Transnational of the Brown Atlantic". Portuguese Studies. 35 (2): 136–53. doi:10.5699/portstudies.35.2.0136. ISSN 0267-5315. JSTOR 10.5699/portstudies.35.2.0136. S2CID 213802402.

- ^ Spaulding, Rachel (26 June 2015). The Word and The Flesh: The Transformation of Female Slave Subject to Mystic Agent through Performance in the Texts of Úrsula de Jesus, Theresa (Chicaba) de Santo Domingo and Rosa Maria Egipcíaca (PhD Thesis). University of New Mexico.

- ^ Souza, Laura de Mello e (29 March 2017). "Popular Religion in Colonial Brazil". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.276. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Spaulding, Rachel (1 December 2016). "Covert Afro-Catholic agency in the mystical visions of early modern Brazil's Rosa Maria Egipçíaca". In Díaz, Mónica; Quispe-Agnoli, Rocío (eds.). Women's Negotiations and Textual Agency in Latin America, 1500–1799. Routledge. pp. 50–73. doi:10.4324/9781315401027-15. ISBN 978-1-315-40102-7.

- ^ Maia, Moacir Rodrigo de Castro. De reino traficante a povo traficado: A diáspora dos courás do golfo do Benim para Minas Gerais (América Portuguesa, 1715–1760) (PDF). Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional. p. 19. ISBN 9788570090034.

- ^ Marcela de Arajuo Pinto (2014). Lares Literários: Metáforas de nacionalidade em Paradise (1997), de Toni Morrison, e em Rosa Maria Egipcíaca da Vera Cruz (1997), de Heloisa Maranhão (PDF). Cultura Acadêmica. pp. 32–.

- ^ Maranhão, Heloísa (1997). Rosa Maria Egipcíaca da Vera Cruz : a incrível trajetória de uma princesa negra entre a prostituição e a santidade. [Rio de Janeiro, Brazil]: Editora Rosa dos Tempos. ISBN 8501047570. OCLC 605428230.

- ^ "SciELO Books | Rosae: linguística histórica, história das línguas e outras histórias". books.scielo.org. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Myscofski, Carole A. (26 April 2019). "Women and the Catholic Church in Colonial Brazil". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.657. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Assunção, Matthias Röhrig (2003). "From Slave to Popular Culture: The Formation of Afro-Brazilian Art Forms in Nineteenth-Century Bahia and Rio de Janeiro". Iberoamericana. 3 (12): 159–176. ISSN 1577-3388. JSTOR 41674077.

- ^ Monica Diaz; Rocio Quispe-Agnoli. "Introduction" (PDF). In Allison Poska; Abby Zanger (eds.). Women's Negotiations and Textual Agency in Latin America, 1500-1799. Women and Gender in the Early Modern World. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 1–15.