The robust crow or slender-billed crow (Corvus viriosus) was a species of large, raven-sized crow that was endemic to the islands of Oahu and Molokai in the Hawaiian Islands during the Holocene. C. viriosus was frugivorous and was adapted for this with a long, slender bill. It was pushed to extinction due to the arrival of people and pests like rats.

| Robust crow | |

|---|---|

| |

| The holotype skeleton of C. viriosus. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Corvus |

| Species: | †C. viriosus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Corvus viriosus Olson & James, 1991

| |

Etymology

editThe specific name viriosus comes from the Latin word viriosus meaning "robust" and "strong" after the species' larger size when compared to Corvus hawaiiensis and the sturdy construction of the holotype's cranium and mandible.[1]

Discovery and taxonomy

editAlthough it may have coexisted with humans, the first recorded fossils of Corvus viriosus were collected by Storrs L. Olson, an American ornithologist who was working for the National Museum of Natural History, USA at the time, on July 26, 1977, from a flooded cavern in Barbers Point, Oahu, Hawaiian islands, the fossils dating to the Quaternary.[2][1] The fossils from Barbers Point consisted of a single, incomplete skeleton (USNM 386435) that included a partial skull, mandible, and several postcranial elements that were found on the floor of the cavern near a specimen of the related Corvus impluviatus. Another specimen consisting only of a fragmentary skull and partial mandible of C. viriosus that was found on the Hawaiian island Molokai was also referred to C. viriosus. C. viriosus was not mentioned in a published scientific article until 1982 when Olson and fellow USNM ornithologist, Helen F. James, who nicknamed it the "slender-billed species",[3] but it was properly named C. viriosus by the two in 1991, with the Oahu skeleton (USNM 386435) designated the holotype, name specimen, and the Molokai fossils (BBM-X 148156) were made the paratype, another specimen that is part of the type series of specimens.[1]

The geographic location and the close similarities between Hawaiian Corvus species suggests that all species originated from a single common ancestor that settled in Hawaii, as hypothesized by Olson & James (1991). However, the two stated that this ancestor, as well as the ancestor of Hawaiian ravens, was not from North America and instead came from Australasia.[1]

Description

editCorvus viriosus was a large species of Corvus with a long, straight bill, deep mandibular ramus, and short tarsometatarsus compared to other species like C. meeki and C. woodfordi. The bill is straighter and has a more narrow dorsal nasal bar compared to C. woodfordi and also a smaller interorbital fenestra with a less elongate narial opening compared to C. macrorhynchus, C. corax, and several other species. C. viriosus also differs from the former species in that the maxillary rostrum is less arched anteriorly; C. viriosus also had a deeper bill, broader nasal bar, and more ossified nasal cavities than C. corax. C. moriorum, another Corvus species, has a larger cranial fenestra, less ossified nasal cavities, shallower mandibular ramus, and a smaller articular mandible end than C. viriosus. C. viriosus differs from the other Hawaiian species C. hawaiiensis and C. impluviatus in that its bill is longer, straighter, less deep, and has a more pronounced excavation of the ventral maxilla. The nasal bars were also narrower, the mandibular symphysis was longer, and the tomial crest, or cutting edge, of the mandible was straighter. C. viriosus has rounded posterior mandibular fossae, or openings, the frontals are less broad, the postorbital processes are slimmer, and the transpalatine process is square tipped, while it is broad and rounded in C. hawaiiensis and C. impluviatus. C. viriosus is like C. hawaiiensis but differs from C. impluviatus in that it has a narrower dorsal nasal bar, a slimmer zygomatic process, a stouter olecranon on the humerus, and a shorter posterior projection on the ilium. In the postcrania, the olecranal fossa on the humerus lacks the deep, rounded pit found in other Hawaiian corvids.[1][3]

Paleobiology

editLike other crow species, C. viriosus was an omnivorous bird with a beak adapted to consume different foods, but its larger size suggests that it ate different kinds of food than extant crows or other Hawaiian ones. On the Hawaiian islands that the species lived on, there were no large terrestrial mammals so Corvus and other birds filled the empty ecological role. C. viriosus was primarily a frugivore and possibly ate seeds as well based on its classification and morphology, though detailed analysis of its diet has not been conducted. The slender and curved mandible could have been used for easier frugivory, as in modern finches and crows.[4]

Paleoenvironment

editCorvus viriosus lived on the Hawaiian Islands of Oahu and Molokai, two of the central islands in the archipelago, which had lush, high-elevation forests on the mountainous areas and sea cliffs. The lower parts of the islands were much drier and had their own distinct flora and fauna, but many of the native species that lived in the lowlands have gone extinct due to human colonization.[5] C. viriosus lived only in the lowlands and large sand dunes by the beaches, while many other bird species lived in the forests, suggesting niche partitioning between birds on the island.[6]

Extinction

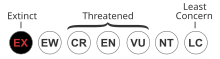

editBy the time Europeans arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in 1778, C. viriosus and many other Hawaiian crow species had gone extinct, the only extant native Corvus species being C. hawaiiensis. Most extinct Hawaiian bird species, including C. viriosus, went extinct likely due to hunting and habitat destruction by Polynesian humans, who first colonized the islands around 1000 CE, and also brought animals that possibly hunted the birds to extinction after the Polynesians imported them in the 18th century.[7][3] Although hunting by humans and imported animals played a role, the destruction of habitats by Polynesians, usually by fire, to make space for agriculture was likely the cardinal factor in the species’ extinction.[8] This is supported not only by fossil and archaeological evidence, but also writings by British explorers like David Nelson describe extensive deforestation in the lowlands that C. viriosus inhabited.[9][8] At the site of the holotype's discovery in Barbers Point, Oahu, charcoal from a hearth and fossils of several animals that had been imported such as bones of the Pacific rat and shells from land snails were unearthed and dated to as recently as 770 CE.[6][10] Bones of cooked native Hawaiian birds also suggest that birds were regularly consumed and cooked by steaming.[3]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e James, H. F., & Olson, S. L. (1991). Descriptions of thirty-two new species of birds from the Hawaiian Islands: Part II. Passeriformes. Ornithological Monographs, (46), 1-88.

- ^ Segui, B., & Alcover, J. A. (1999). Comparison of paleoecological patterns in insular bird faunas: a case study from the western Mediterranean and Hawaii. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, (89).

- ^ a b c d Olson, S. L., & James, H. F. (1982). Prodromus of the fossil avifauna of the Hawaiian Islands.

- ^ Corlett, Richard T. (2017-07-01). "Frugivory and seed dispersal by vertebrates in tropical and subtropical Asia: An update". Global Ecology and Conservation. 11: 1–22. Bibcode:2017GEcoC..11....1C. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2017.04.007. ISSN 2351-9894.

- ^ Rock, Joseph Francis (1913). The Indigenous Trees of the Hawaiian Islands. T. H.

- ^ a b Olson, S. L., & James, H. F. (1982). Fossil birds from the Hawaiian Islands: evidence for wholesale extinction by man before western contact. Science, 217(4560), 633-635.

- ^ Gane, Daniel Charles (2021). The Pacific self : oceanic narratives and self-representation in accounts of eighteenth-century British voyages of Pacific exploration (Thesis thesis). Newcastle University.

- ^ a b St John, H. (1976). Biography of David Nelson, and an account of his botanizing in Hawaii.

- ^ St John, H. (1976). New Species of Hawaiian Plants Collected by David Nelson in 1779 Hawaiian Plant Studies 52.

- ^ Kirch, P. V., & Christensen, C. C. (1981). Nonmarine molluscs and paleoecology at Barber’s Point, O ‘ahu. Appendix II. HH Hammatt, and WH Folk II, Archaeological and paleontological investigation at Kalaeloa (Barber’s Point), Honouliuli,‘Ewa, O ‘ahu, Federal Study Areas 1a and 1b, and State of Hawai ‘i Optional Area, 1, 242-286.