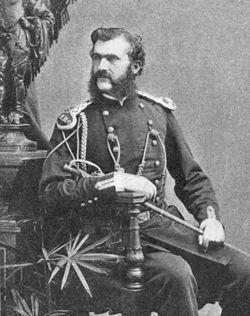

Richard Henry Savage (June 12, 1846 – October 11, 1903) was an American military officer and author who wrote more than 40 books of adventure and mystery, based loosely on his own experiences. Savage's life may have been the inspiration for the pulp novel character Doc Savage.

Richard Henry Savage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 12, 1846 Utica, New York |

| Died | October 11, 1903 (aged 57) New York City |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | United States Army Egyptian Army California National Guard |

| Years of service | 1868–70, 1871–72, 1877–79, 1898–99 |

| Rank | Captain, Egyptian Army Major, U.S. Army Colonel, National Guard |

| Battles / wars | Spanish–American War |

| Other work | Author, diplomat, engineer, attorney |

In his youth in San Francisco, Savage studied engineering and law, and graduated from the United States Military Academy. After a few years of surveying work with the Army Corps of Engineers, Savage went to Rome as an envoy following which he sailed to Egypt to serve a stint with the Egyptian Army. Returning home, Savage was assigned to assess border disputes between the U.S. and Mexico, and he performed railroad survey work in Texas. In Washington D.C., he courted and married a widowed noblewoman from Germany.

Savage returned to San Francisco with his wife to stay for ten years, raising a daughter and taking part in a family business. He served at the rank of colonel in the California National Guard, and took part in the social activity of the city. During a period [when?] of anti-Chinese race riots, Savage stood up for law and order, and thereby gained the respect of San Francisco's leaders, property holders and middle class residents. Savage traveled to many exotic lands but in 1890 he was struck with jungle fever in Honduras. While recuperating in New York state he wrote his first book: My Official Wife. This very successful action-and-adventure story was followed by more, at the rate of about three per year, written for the general public rather than for literary critics; the latter were charmed by the first book but scathing of many later ones. Savage lived primarily in New York City, and was involved in lawsuits, especially against his New York publisher regarding unpaid royalties.

When the Spanish–American War broke out, Savage volunteered to lead men in battle. Instead, he was given command of an engineering unit which then built a complete base in Havana. Returning to New York, he wrote more books and corresponded with his wife who traveled often to the Russian Empire to visit their daughter and her Russian husband. Four years after mustering out of the Army, Savage was knocked down and mortally wounded at the age of 57 by a horse and carriage on the streets of New York.

Early life and career

editSavage was born in Utica, New York, the son of Jane Moorhead Ewart and Richard Savage (1817–1903), a lawyer and manufacturer whose family had lived in the Utica area for years.[1] The 1848 finding of gold in California, prompted Savage's father to join the California Gold Rush in 1850. Savage and the rest of his family left New York in 1851 to join his father.[1] They arrived in San Francisco in February 1852.[2] Savage was among the first boys to attend public school in the new city, along with future poet Charles Warren Stoddard and the brothers Gus, Charles and Harry de Young who would found the San Francisco Chronicle.[3] While the younger Savage was in school, his father helped discover the rich silver deposits of the Comstock Lode.[4]

Savage finished high school at age 15 and began to study law with U.S. Senator James A. McDougall. Later, he studied with the law firm Halleck, Peachy & Billings, while partner Henry Halleck was back East serving as major general in the Union Army.[1] At the start of the American Civil War Savage joined the Union Army, but his father secured his discharge on the grounds of his extreme youth. Savage's father used his influence to push for California to stay on the Union side, and was rewarded by President Lincoln with the post of Collector of Internal Revenue in which capacity he served between 1861 and 1873. Through government connections, Savage's father gained for Savage an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1864. Despite the danger of Confederate privateers, Savage chose to travel east by way of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company to the Isthmus of Panama, followed by the Atlantic leg to New York, but significant wartime delays prevented him from joining the summer plebes at the academy. Rather, he took his place with the September students. In 1868, Savage graduated sixth in his class of 55 at West Point,[5] and was assigned as brevet second lieutenant with the Army Corps of Engineers at Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco Bay. (The "brevet" rank acknowledged that Savage was needed as a second lieutenant despite the US government limiting the number of serving army officers.) Savage took part in survey work on the Indian reservations of Round Valley in Northern California and the Pima and Maricopa reservations in Arizona.[1][6]

Government and writing career

editSavage performed his Army tasks but was unhappy with the narrowly defined role. He tendered his resignation on December 31, 1870.[1] Through President Grant, he went to Marseilles and Rome as an American vice-consul.[1] In 1871, Savage traveled to Egypt to act with the rank of captain for one year as secretary to Charles Pomeroy Stone, a former American general in the Egyptian Army, serving under Khedive Isma'il Pasha.[1] Following an honorable discharge from the Egyptian Army, Savage returned to the U.S. and was tasked by Grant to serve as one of three commissioners investigating a series of border incidents between the U.S. and Mexico 1872–74. At the same time, he worked with Richard King and the nascent Corpus Christi & Rio Grande Railroad as chief surveyor for the route to Laredo.[1]

At the German Embassy in Washington, D.C., on January 2, 1873, Savage married the aristocratic Anna Josephine Scheible,[1] a German widow three months older than he who had arrived in war-torn America in 1864 with her first husband, Gustav, to look after family-owned land in Georgia. Gustav Scheible died in 1866 and Anna became a favorite of the Washington social circle.[7] Her marriage to Savage produced one daughter, who later married Anatol de Carriere, a minor nobleman and an Imperial Russian Councilor of State.[8]

In 1874, Savage began a ten-year stay in San Francisco. He worked with his father and brother on an iron foundry enterprise, and served two years as colonel of the 2nd Regiment California National Guard.[1] Savage took a prominent role in the civic and social life of the city, and was often called upon to make extemporaneous speeches to large crowds, a skill on which politician and economist Henry George complimented him.[1] In January 1878, Savage served as chief military executive officer of the Committee of Safety, a group set up to oppose Denis Kearney and his riotous mob of angry supporters who wanted to get rid of Chinese immigrants.[9] Savage's calm and logical presence was seen by San Franciscans as a rallying point for law and order during the riots.[1] Savage renewed the friendship of his childhood schoolmate, now Bohemian Club poet Charles Warren Stoddard. He made the acquaintance of writer Archibald Clavering Gunter, who would later publish some of Savage's stories.[1]

While in San Francisco, Anna Savage began a devoted interest in the fight for women's suffrage.[7] Savage retired from government service in 1884 to practice law with his youngest brother. In 1890, he moved to New York City.[1]

In late 1890 at a friend's house on Lake George in upstate New York, while recovering from a near-fatal case of jungle fever contracted in Honduras, Savage wrote a tale loosely based on his life, entitled My Official Wife. The book was a great success, and was translated into many languages.[1] The Times in London called it "a wonderful and clever tour de force, in which improbabilities and impossibilities disappear, under an air that is irresistible."[10]

Savage followed his first book with Delilah of Harlem, The Mask of Venus, Our Mysterious Passenger and Other Stories and In the Shadow of the Pyramids. In addition to his fiction prose output, Savage published collections of his speeches and essays, and in 1895 wrote a book of poetry dedicated to his wife: After Many Years.[3] Savage's writing style was fast and precise: he wrote from morning to night and rarely needed to correct his first drafts. He was able to carry on a conversation while writing.[3] He joined the Author's Guild of America in 1894.[1]

Critical review

editIn 1893, Savage's book The Masked Venus was scathingly reviewed in the Overland Monthly:

Colonel Richard Henry Savage's career as a novelist has been one of unbroken and rapid decline in the grade of work. My Official Wife was a delicious story, novel in situations and treatment, and simply and well told. The Little Lady of Lagunitas also pleased many people. Prince Schamyl's Wooing was markedly inferior to either, both in plot and style, and sadly marred by blood-and-thunderism. The last of the series yet to hand is The Masked Venus, and it is undoubtedly the worst of all. [...] The style is bombastic, the plot impossible, and the tone bad. [...] The fatal Custer campaign is the climax,—if there can be said to be a climax to a story that endeavors to keep the excitement up to the climax pitch through nearly its whole length,—and there is throughout a lack of moderation, of repose, of proportion, that makes the book a dime novel and not literature.[11]

Savage's In the Shadow of the Pyramids was reviewed in The Literary World in May 1898. The reviewer said that Savage used "a happy mixture of audacity and ignorance quite untrammeled by facts."[12] The "absurd" main character was criticized as unrealistically exposed to mortal danger almost daily, "just escaping dagger thrusts and pistol shots, with results more favorable to the theatrical progress of the story than to his common sense."[12] The previous month in the same periodical, Savage's 25¢ book For Life and Love was dismissed as "a slap-dash romance".[13]

Final decade

editIn 1896, Savage sued his publisher for $12,000 in unpaid royalties. The publisher, Frank Tennyson Neely, who had filed for bankruptcy five years earlier before accepting Savage as a client, argued that he did not owe Savage anything, instead, Savage owed him. Neely's scattered and incomplete accounting books prevented an easy conclusion to the trial.[14] Three years later, Neely once again declared bankruptcy.[15] In 1899, Abraham Lewis of Brooklyn sued Savage for $10,000 in damages, for stealing away the affections of his wife. Savage's own wife and a friend defended him in court, saying Lewis, an informal supplier of food to soldiers under Savage's command, was retaliating for being stopped from the lucrative but illegal act of selling liquor to the troops at Montauk Point.[16]

On January 3, 1898, Savage and his wife celebrated their 25th anniversary, in New York City. On February 16, Savage volunteered for Army duty during the Spanish–American War. Savage would have served as lieutenant colonel of the 1st Tammany Regiment, but New York's Governor Frank S. Black declined the formation. Savage was instead assigned senior major of the 2nd U.S. Volunteer Engineers at the end of May. After stateside training and the building of a complete Army camp at Montauk Point, his unit traveled in November to Havana, Cuba and cleared Marianao to build Camp Columbia for the Army of Occupation. Savage hoisted the first American flag in Havana Province on December 10. He was in command of the battalion at the surrender of Havana on January 1, 1899.[5] Weakened with yellow fever, Savage was mustered out of the Volunteer Engineers in April, 1899, and assigned captain with the 27th Volunteer Infantry. Continuing illness prevented him from traveling with his unit to the Philippines, and he was honorably discharged.[1]

In August 1903, Savage's wife and daughter were in Kishinev, Russia, where Savage's son-in-law Anatol de Carriere was serving the Russian government. Savage's wife sent word through Breslau to London that 27 of the Kishinev pogrom rioters had been given prison sentences. The de Carrieres hid some 40 Jews in their house during the rioting. Anna Savage warned that if further bloody riots were encouraged by the Tsar's government, "the wealthy Russian aristocracy will be in danger of their lives."[17]

Death and legacy

editSavage died on October 11, 1903, at Roosevelt Hospital after being knocked down and injured in the ribcage on a New York City street by a horse and wagon on October 3. Savage's wife and daughter were still in Europe at the time of his death.[18] He was buried at the West Point Cemetery on October 14, 1903.[19]

Anna Josephine Savage died at the age of 67 on July 7, 1910, after a long illness in New York City, with her daughter at her side. For 30 years, she had been a noted supporter of women's right to vote.[7]

Author Marilyn Cannaday has suggested that Doc Savage, the pulp hero from the 1930s and 1940s, was based in part on Savage's life, or at least his name. Though he never met Savage, Henry Ralston, one of men who created the pulp character, joined Street and Smith publishers one year after a collection of Savage's short stories were published.[20]

Selected works

edit- (1891) My Official Wife, at Google Books

- (1891) My Official Wife, at Internet Archive

- (1892) The Little Lady of Lagunitas: A Franco-Californian Romance, at Project Gutenberg

- (1892) The Little Lady of Lagunitas: A Franco-Californian Romance, at Internet Archive

- (1892) Prince Schamyl's Wooing: A Story of the Caucasus-Russo-Turkish War (1892), at Internet Archive

- (1893) Of Life and Love: A Story of the Rio Grande, at Internet Archive

- (1893) Delilah of Harlem: A Story of the New York City of To-Day, at Internet Archive

- (1894) The Anarchist: A Story of To-Day, at Internet Archive

- (1894) The Princess of Alaska: A Tale of Two Countries, at Internet Archive

- (1894) The Flying Halcyon: a mystery of the Pacific Ocean, at Google Books

- (1895) Miss Devereux of the Mariquita: A Story of Bonanza Days in Nevada, at Internet Archive

- (1895) His Cuban Sweetheart, at Internet Archive

- (1895) After Many Years, at Internet Archive

- (1896) An Exile from London: A Novel, at Internet Archive

- (1896) Lost Contessa Falka: A Story of the Orient, at Internet Archive

- (1896) Checked Through, Missing, Trunk No. 17580: A Story on New York City Life, at Internet Archive

- (1897) An Awkward Meeting, Fighting the Tiger and other Thrilling Adventures, at Internet Archive

- (1897) A Fascinating Traitor, at Project Gutenberg

- (1897) Captain Landon: A Story of Modern Rome, at Internet Archive

- (1897) A Modern Corsair: A Story of the Levant, at Internet Archive

- (1898) In The Swim: A Story of Currents and Under-Currents in Gayest New York, at Internet Archive

- (1899) His Cuban Sweetheart, at Internet Archive

- (1899) The White Lady of Khaminavatka: A Story of the Ukraine, at Google Books

- (1900) The Midnight Passenger, at Project Gutenberg

- (1902) The Mystery of a Shipyard, at Internet Archive

- (1904) The Last Traitor of Long Island: A Story of the Sea, at Internet Archive

- (1904) The Last Traitor of Long Island: A Story of the Sea, at Internet Archive

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Stark Family Association, United States Military Academy. Annual Reunion, June 14th, 1904. Richard Henry Savage. No. 2224, Class of 1868. pp. 111–120. Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ John J. Daly, ed. (May 1897). "Richard Henry Savage". The Bookseller and Newsman. 14 (5). New York: 11.

- ^ a b c Stoddard, Charles Warren. Pacific Monthly, December 1907. "In Old Bohemia: Memories of San Francisco in the Sixties". Retrieved on July 26, 2009.

- ^ Western Historical Publishing (1892). Master hands in the affairs of the Pacific Coast: historical, biographical and descriptive. A resumé of the builders of our material progress. San Francisco: Western Historical Publishing. p. 49. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ^ a b Cullum, George Washington; United States Military Academy. Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy, Houghton, Mifflin, 1901, p. 177.

- ^ Cullum, George Washington; United States Military Academy. Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy, Houghton, Mifflin, 1891, p. 108.

- ^ a b c The New York Times, July 8, 1910. "Mrs. Richard Savage Dead". Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, June 26, 1913. "Says Russia Won't Yield On Passports; Indifferent to Our Demands, American Wife of Imperial Councilor Thinks." Retrieved on January 23, 2010.

- ^ The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. The Sand Lot and Kearneyism, Jerome A. Hart. Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ Current Opinion, p. 177. Current Literature Pub. Co, 1891

- ^ The Overland Monthly, 1893. "Recent Fiction", p. 661

- ^ a b Edward Abbott, ed. (May 14, 1898). "The Literary World". 29 (10). Boston: Samuel R. Crocker: 185.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Edward Abbott, ed. (April 2, 1898). "The Literary World". 29 (7). Boston: Samuel R. Crocker: 102.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The New York Times, September 3, 1896. "A Wagonload of Books; Produced by F.T. Neely in Col. Savage's Suit". Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, October 22, 1899. "F. Tennyson Neely Bankrupt; Liabilities Placed at $359,531.76 and Assets $414,739,27." Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, November 25, 1899. "Husband Sues Col. Savage; Author and Soldier Accused of Alienating a Wife's Affections". Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, August 1, 1903. "Russia's guilt at Kishineff". Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, October 12, 1903. "Richard H. Savage Dead". Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ^ "Savage, Richard Henry". Army Cemeteries Explorer. U.S. Army. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Cannaday, Marilyn. Bigger than Life: the creator of Doc Savage, Popular Press, 1990, pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-87972-471-4

External links

edit- Works by Richard Henry Savage at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Richard Henry Savage at the Internet Archive

- Works by Richard Henry Savage at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)