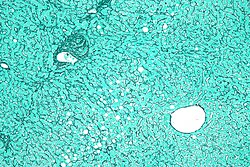

Reticular fibers, reticular fibres or reticulin is a type of fiber in connective tissue[1] composed of type III collagen secreted by reticular cells.[2] They are mainly composed of reticulin protein and form a network or mesh. Reticular fibers crosslink to form a fine meshwork (reticulin). This network acts as a supporting mesh in soft tissues such as liver, bone marrow, and the tissues and organs of the lymphatic system.[3]

History

editThis section contains overly lengthy quotations. (May 2015) |

The term reticulin was coined in 1892 by M. Siegfried.[4]

Today, the term reticulin or reticular fiber is restricted to referring to fibers composed of type III collagen. However, during the pre-molecular era, there was confusion in the use of the term reticulin, which was used to describe two structures:

- the argyrophilic (silver staining) fibrous structures present in basement membranes

- histologically similar fibers present in developing connective tissue.[5]

The history of the reticulin silver stain is reviewed by Puchtler et al. (1978).[6] The abstract of this paper says:

Maresch (1905) introduced Bielschowsky's silver impregnation technic for neurofibrils as a stain for reticulum fibers, but emphasized the nonspecificity of such procedures. This lack of specificity has been some confirmed repeatedly. Yet, since the 1920s the definition of "reticulin" and studies of its distribution were based solely on silver impregnation technics. The chemical mechanism and specificity of this group of stains is obscure. Application of Gömöri's and Wilder's methods to human tissues showed variations of staining patterns with the fixatives and technics employed. Besides reticulum fibers, various other tissue structures, e.g. I bands of striated muscle, fibers in nervous tissues, and model substances, e.g. polysaccharides, egg white, gliadin, were also stained. Deposition of silver compounds on reticulum fibers was limited to an easily removable substance; the remaining collagen component did not bind silver. These histochemical studies indicate that silver impregnation technics for reticulum fibers have no chemical significance and cannot be considered as histochemical technics for "reticulin" or type III collagen.

Structure

editReticular fiber is composed of one or more types of very thin and delicately woven strands of type III collagen. These strands build a highly ordered cellular network and provide a supporting network. Many of these types of collagen have been combined with carbohydrate. Thus, they react with silver stains(argyrophilic) and with periodic acid-Schiff reagent but are not demonstrated with ordinary histological stains such as those using hematoxylin. The 1953 Science article mentioned above concluded that the reticular and regular collagenous materials contains the same four sugars – galactose, glucose, mannose, and fucose – but in a much greater concentration in the reticular than in the collagenous material.

In a 1993 paper, the reticular fibers of the capillary sheath and splenic cord were studied and compared in the pig spleen by transmission electron microscopy.[7] This paper attempted to reveal their components and the presence of sialic acid in the amorphous ground substance. Collagen fibrils, elastic fibers, microfibrils, nerve fibers, and smooth muscle cells were observed in the reticular fibers of the splenic cord. On the other hand, only microfibrils were recognized in the reticular fibers of the capillary sheath. The binding of LFA lectin to the splenic cord was stronger than the capillary sheath. These findings suggested that the reticular fibers of the splenic cord include multiple functional elements and might perform an important role during contraction or dilation of the spleen. On the other hand, the reticular fiber of the capillary sheath resembled the basement membrane of the capillary in its components.

Because of their affinity for silver salts, these fibers are called argyrophilic.

References

edit- ^ "reticular fibers" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Strum, Judy M.; Gartner, Leslie P.; Hiatt, James L. (2007). Cell biology and histology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7817-8577-8.

- ^ Burkitt, H. George; Young, Barbara; Heath, John W. it is made up of white collegent fibre = gogulakrishnan green park Namakal class 11 cb3; Wheater, Paul R. (1993). Wheater's Functional Histology (3rd ed.). New York: Churchill Livinstone. p. 62. ISBN 0-443-04691-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Siegfried, M. (1892). Habilitationsschrift. Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus. Cited in Glegg, R. E.; Eidinger, D.; Leblond, C. P. (1953). "Some Carbohydrate Components of Reticular Fibers". Science. 118 (3073): 614–6. Bibcode:1953Sci...118..614G. doi:10.1126/science.118.3073.614. PMID 13113200.

- ^ Jackson, D. S.; Williams, G. (1956). "Nature of Reticulin". Nature. 178 (4539): 915–6. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..915J. doi:10.1038/178915b0. PMID 13369574. S2CID 4183191.

- ^ Puchtler, Holde; Waldrop, Faye Sweat (1978). "Silver impregnation methods for reticulum fibers and reticulin: A re-investigation of their origins and specifity". Histochemistry. 57 (3): 177–87. doi:10.1007/BF00492078. PMID 711512. S2CID 6445345.

- ^ Miyata, Hiroto; Abe, Mitsuo; Takehana, Kazushige; Iwasa, Kenji; Hiraga, Takeo (1993). "Electron Microscopic Studies on Reticular Fibers in the Pig Sheathed Artery and Splenic Cords". The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 55 (5): 821–7. doi:10.1292/jvms.55.821. PMID 8286537.

External links

edit- Reticulin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- MedEd at Loyola Histo/practical/stains/hp2-55.html