The Rasphuis was a "tuchthuis" or prison in Amsterdam that was established in 1596 in the former Convent of the Poor Clares on the Heiligeweg. In 1815 it was closed, and in 1892 the building was demolished to make way for a swimming pool. On the site today is the Kalvertoren shopping centre.

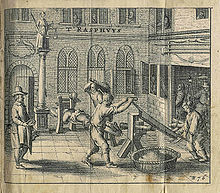

The Rasphuis was a prison for young male criminals. Female criminals were sent to the Spinhuis. The detainees in the Rasphuis were made to shave wood from the brazilwood tree (Caesalpinia echinata or pernambuco), rasping it into powder using an eight to twelve bladed rasp, hence the name. The powder was delivered as a raw material to the paint industry where it was mixed with water, then boiled and oxidised to form a red pigment, also known as brazilwood, which in turn was used as a textile dye.

Founding

editThe Rasphuis was founded after the torture of 16-year-old assistant tailor Evert Jansz. Jansz confessed, as a result of the torture, to theft on two occasions from his boss. The usual punishment for this was public flogging, but the city council decided to try to rehabilitate Jansz, who was from a good background. Under the influence of Dirck Volkertszoon Coornhert and C.P. Hooft the city decided, on 19 June 1589, to build a prison. Shortly after the opening, Jansz was sentenced to a light beating and forced labour; he never took the rasp.

The founding of the Rasphuis signified a sea-change in Dutch correctional thinking. Until then it was universally believed that criminals needed to be punished. In the Rasphuis, the effort was made to instill a sense of order and duty into the young men. The Rasphuis was thus intended as an institute for rehabilitation. Over the entrance gate, which still stands, is the inscription 'Wilde beesten moet men temmen' or 'Wild beasts must be tamed'.

There is a persistent myth that the Rasphuis contained a "water dungeon," the so-called Waterhuis.[1] If prisoners refused to work they were placed in a cellar that quickly filled with water after a sluice was opened; they were handed a pump that enabled them to keep from drowning, provided they pumped energetically and continuously. Geert Mak and other historians, however, point out that there is no evidence whatsoever for the existence of this room and this punishment.[2]

Exploitation

editWithin a few years, however, the Rasphuis began to be exploited as a source of cheap labour and the rehabilitation goals envisaged by the founders were lost. More and more adults were incarcerated in the Rasphuis. A secret section was created where families could lock up uncontrollable or otherwise crazy relatives, at their own cost. These prisoners were seen as privileged due to the meals of dried fish, salted meat or bacon they received once a week as opposed to the standard menu of peas and pearl barley served to other inmates.

For a fee, the Rasphuis could be visited, for example by families wishing to let their children see what would become of them if they were not well-behaved.

For a long time, the Rasphuis had a monopoly in parts of the Netherlands for the processing of brazilwood. A mill was built in Zaandam in 1601 to process brazilwood, but this mill worked under the control of the Rasphuis. Inspectors worked in the Zaanstreek to ensure that the monopoly was adhered to. The quality and delivery from the Rasphuis left much to be desired however and, over time, this monopoly was weakened due to increased competition from other sources. During the French occupation of the Netherlands the cities lost their right to impose monopolies and this monopoly too, came to an end. In 1815 the Rasphuis was closed.

The inside of the Rasphuis was depicted in a sketch by van Toornenbergen in 1799.

Notes

edit- ^ Pol, Lotte van der (1996). Het Amsterdams hoerdom: prostitutie in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Wereldbibliotheek. p. 192.

Het rasphuis had opvallend genoeg ook een hardnekkige mythe. In dit tuchthuis voor mannen zou een 'waterhuis' of verdrinkingscel zijn waarin gevangenen werden gezet die niet wilden werken.

- ^ Mak, Geert (1994). Een kleine geschiedenis van Amsterdam. Atlas. p. 180. ISBN 978-90-254-0416-1.

Jacob Bicker Raye en enkele anderen melden zelfs het - overigens onbevestigde - bestaan van een 'waterhuis'.

References

edit- Sellin, Thorsten (1944). Pioneering in Penology. University of Pennsylvania Press, Oxford Press.

- University of Amsterdam. The Rasphuis (Library Exhibitions)(in Dutch). University of Amsterdam. 2009-02-26. URL:http://www2.ic.uva.nl/uvalink/uvalink14/zicht14.htm. Accessed: 2009-02-26. (Archived by WebCite at https://www.webcitation.org/5esEMBDDI)