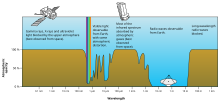

The radio window is the region of the radio spectrum that penetrate the Earth's atmosphere. Typically, the lower limit of the radio window's range has a value of about 10 MHz (λ ≈ 30 m); the best upper limit achievable from optimal terrestrial observation sites is equal to approximately 1 THz (λ ≈ 0.3 mm).[1][2]

It plays an important role in astronomy; up until the 1940s, astronomers could only use the visible and near infrared spectra for their measurements and observations. With the development of radio telescopes, the radio window became more and more utilizable, leading to the development of radio astronomy that provided astrophysicists with valuable observational data.[3]

Factors affecting lower and upper limits

editThe lower and upper limits of the radio window's range of frequencies are not fixed; they depend on a variety of factors.

Absorption of mid-IR

editThe upper limit is affected by the vibrational transitions of atmospheric molecules such as oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and water (H2O), whose energies are comparable to the energies of mid-infrared photons: these molecules largely absorb the mid-infrared radiation that heads towards Earth.[4][5]

Ionosphere

editThe radio window's lower frequency limit is greatly affected by the ionospheric refraction of the radio waves whose frequencies are approximately below 30 MHz (λ > 10 m);[6] radio waves with frequencies below the limit of 10 MHz (λ > 30 m) are reflected back into space by the ionosphere.[7] The lower limit is proportional to the density of the ionosphere's free electrons and coincides with the plasma frequency: where is the plasma frequency in Hz and the electron density in electrons per cubic meter. Since it is highly dependent on sunlight, the value of changes significantly from daytime to nighttime usually being lower during the day, leading to a decrease of the radio window's lower limit and higher during the night, causing an increase of the radio window's lower frequency end. However, this also depends on the solar activity and the geographic position.[8]

Troposphere

editWhen performing observations, radio astronomers try to extend the upper limit of the radio window towards the 1 THz optimum, since the astronomical objects give spectral lines of greater intensity in the higher frequency range.[9] Tropospheric water vapour greatly affects the upper limit since its resonant absorption frequency bands are 22.3 GHz (λ ≈ 1.32 cm), 183.3 GHz (λ ≈ 1.64 mm) and 323.8 GHz (λ ≈ 0.93 mm). The tropospheric oxygen's bands at 60 GHz (λ ≈ 5.00 mm) and 118.74 GHz (λ ≈ 2.52 mm) also affect the upper limit.[10] To tackle the issue of water vapour, many observatories are built at high altitudes where the climate is more dry.[11] However, few can be done to avoid the oxygen's interference with radio waves propagation.[12]

Radio frequency interference

editThe width of the radio window is also affected by radio frequency interference which hinders the observations at certain wavelength ranges and undermines the quality of the observational data of radio astronomy.[13]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Condon, James J.; Ransom, Scott M. (2016). Essential Radio Astronomy. Princeton University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-691-13779-7.

- ^ "1 Introduction‣ Essential Radio Astronomy". www.cv.nrao.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-27.

- ^ Wilson, Thomas; Rohlfs, Kristen; Huettemeister, Susanne (2016). Tools of Radio Astronomy. Berlin: Springer-Verlag GmbH. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-3-662-51732-1. OCLC 954868912.

- ^ Liou, Kuo-Nan; Yang, Ping; Takano, Yoshihide (2016). Light scattering by ice crystals: fundamentals and applications. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139030052. ISBN 978-1-139-03005-2. OCLC 958454932.

- ^ Ritchie, Grant (2017). Atmospheric chemistry: from the surface to the stratosphere. World Scientific. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-78634-175-4. OCLC 957339640.

- ^ Anderson, John B.; Johannesson, Rolf (2005). Understanding information transmission. Piscataway, NJ; Hoboken, NJ: IEEE Press, Wiley-Interscience. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-471-67910-3. OCLC 56103934.

- ^ Torge, Wolfgang; Müller, Jürgen (2012). Geodesy. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 121. ISBN 978-3-11-020718-7. OCLC 987088700.

- ^ Warnick, Karl F.; Maaskant, Rob; Ivashina, Marianna V. (2018). Phased arrays for radio astronomy, remote sensing and satellite communications. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-108-42392-2. OCLC 1032582026.

- ^ Wilson, Thomas; Rohlfs, Kristen; Huettemeister, Susanne (2016). Tools of Radio Astronomy. Springer-Verlag GmbH. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-662-51732-1. OCLC 954868912.

- ^ Otung, Ifiok (2021). Communication engineering principles. Wiley. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-119-27402-5. OCLC 1225565245.

- ^ Karttunen, Hannu (2007). Fundamental astronomy. Berlin: Springer-verlag. p. 72. ISBN 978-3-540-34143-7. OCLC 860603182.

- ^ Conference Proceedings. IEEE. 1990. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-87942-557-9. OCLC 25175353.

- ^ McNally, Derek (1994). McNally, Derek; Unesco (eds.). The vanishing universe: adverse environmental impacts on astronomy: proceedings of the conference sponsored by Unesco. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-521-45020-1. OCLC 29359179.