You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (September 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

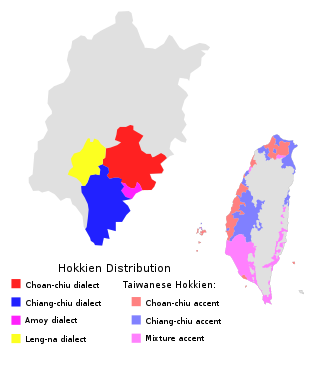

The Quanzhou dialects (simplified Chinese: 泉州话; traditional Chinese: 泉州話; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Choân-chiu-ōe), also rendered Chin-chew or Choanchew,[5] are a collection of Hokkien dialects spoken in southern Fujian (in southeast China), in the area centered on the city of Quanzhou. Due to migration, various Quanzhou dialects are spoken outside of Quanzhou, notably in Taiwan and many Southeast Asian countries, including mainly the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

| Quanzhou | |

|---|---|

| 泉州话 / 泉州話 (Choân-chiu-ōe) | |

| Pronunciation | [tsuan˨ tsiu˧ ue˦˩] |

| Native to | China, Taiwan, Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar. |

| Region | city of Quanzhou, Southern Fujian province |

Native speakers | over 7 million (2008)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Han characters | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | chae1235 |

| Linguasphere | > 79-AAA-jdb 79-AAA-jd > 79-AAA-jdb |

Quanzhou dialect | |

Classification

editThe Quanzhou dialects are classified as Hokkien, a group of Southern Min varieties.[6] In Fujian, the Quanzhou dialects form the northern subgroup (北片) of Southern Min.[7] The dialect of urban Quanzhou is one of the oldest dialects of Southern Min, and along with the urban Zhangzhou dialect, it forms the basis for all modern varieties.[8] When compared with other varieties of Hokkien, the urban Quanzhou dialect has an intelligibility of 87.5% with the Amoy dialect and 79.7% with the urban Zhangzhou dialect.[9]

Cultural role

editBefore the 19th century, the dialect of Quanzhou proper was the representative dialect of Southern Min in Fujian because of Quanzhou's historical and economic prominence, but as Xiamen developed into the political, economic and cultural center of southern Fujian, the Amoy dialect gradually took the place of the Quanzhou dialect as the representative dialect.[10][11] However, the Quanzhou dialect is still considered to be the standard dialect for Liyuan opera and nanyin music.[10][12]

Phonology

editThis section is mostly based on the variety spoken in the urban area of Quanzhou, specifically in Licheng District.

Initials

editThere are 14 phonemic initials, including the zero initial (not included below):[13]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | |||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | /p/ 边 / 邊 |

/t/ 地 |

/ts/ 争 / 爭 |

/k/ 求 |

|

| aspirated | /pʰ/ 普 |

/tʰ/ 他 |

/tsʰ/ 出 |

/kʰ/ 气 / 氣 |

||

| voiced | /b/ 文 |

/ɡ/ 语 / 語 |

||||

| Fricative | /s/ 时 / 時 |

/h/ 喜 | ||||

| Lateral | /l/ 柳 |

|||||

When the rhyme is nasalized, the three voiced phonemes /b/, /l/ and /ɡ/ are realized as the nasal stops [m], [n] and [ŋ], respectively.[13]

The inventory of initial consonants in the Quanzhou dialect is identical to the Amoy dialect and almost identical to the Zhangzhou dialect. The Quanzhou dialect is missing the phoneme /dz/ found in the Zhangzhou dialect due to a merger of /dz/ into /l/.[14] The distinction between /dz/ (日) and /l/ (柳) was still made in the early 19th century, as seen in Huìyīn Miàowù (彙音妙悟) by Huang Qian (黃謙),[14] but Huìyīn Miàowù already has nine characters categorized into both initials.[15] Rev. Carstairs Douglas has already observed the merger in the late 19th century.[16] In some areas of Yongchun, Anxi and Nan'an, there are still some people, especially those in the older generation, who distinguish /dz/ from /l/, showing that the merger is a recent innovation.[14] In Hokkien, evidently even during the early 17th century, /l/ can fluctuate freely in initial position as either a flap [ɾ] or voiced alveolar plosive stop [d].[17]

Rimes

editThere are 87 rimes:[13][18][19]

| /a/ | /ɔ/ | /o/ | /ə/ | /e/ | /ɯ/ | /ai/ | /au/ | ||

| /i/ | /ia/ | /io/ | /iu/ | /iau/ | |||||

| /u/ | /ua/ | /ue/ | /ui/ | /uai/ |

| /m̩/ | /am/ | /əm/ | /an/ | /ŋ̍/ | /aŋ/ | /ɔŋ/ | |

| /im/ | /iam/ | /in/ | /ian/ | /iŋ/ | /iaŋ/ | /iɔŋ/ | |

| /un/ | /uan/ | /uaŋ/ |

| /ã/ | /ɔ̃/ | /ẽ/ | /ãi/ | |||

| /ĩ/ | /iã/ | /iũ/ | /iãu/ | |||

| /uã/ | /uĩ/ | /uãi/ |

| /ap/ | /at/ | /ak/ | /ɔk/ | /aʔ/ | /ɔʔ/ | /oʔ/ | /əʔ/ | /eʔ/ | /ɯʔ/ | /auʔ/ | /m̩ʔ/ | /ŋ̍ʔ/ | /ãʔ/ | /ɔ̃ʔ/ | /ẽʔ/ | /ãiʔ/ | /ãuʔ/ | ||||||

| /ip/ | /iap/ | /it/ | /iat/ | /iak/ | /iɔk/ | /iʔ/ | /iaʔ/ | /ioʔ/ | /iauʔ/ | /iuʔ/ | /ĩʔ/ | /iãʔ/ | /iũʔ/ | /iãuʔ/ | |||||||||

| /ut/ | /uat/ | /uʔ/ | /uaʔ/ | /ueʔ/ | /uiʔ/ | /uĩʔ/ | /uãiʔ/ |

The actual pronunciation of the vowel /ə/ has a wider opening,[dubious – discuss] approaching [ɤ].[13] For some speakers, especially younger ones, the vowel /ə/ is often realized as [e], e.g. pronouncing 飞 / 飛 (/pə/, "to fly") as [pe], and the vowel /ɯ/ is either realized as [i], e.g. pronouncing 猪 / 豬 (/tɯ/, "pig") as [ti], or as [u], e.g. pronouncing 女 (/lɯ/, "woman") as [lu].[10]

Tones

editFor single syllables, there are seven tones:[13][20]

| Name | Tone letter | Description |

|---|---|---|

| yin level (阴平; 陰平) | ˧ (33) | mid level |

| yang level (阳平; 陽平) | ˨˦ (24) | rising |

| yin rising (阴上; 陰上) | ˥˥˦ (554) | high level |

| yang rising (阳上; 陽上) | ˨ (22) | low level |

| departing (去声; 去聲) | ˦˩ (41) | falling |

| yin entering (阴入; 陰入) | ˥ (5) | high |

| yang entering (阳入; 陽入) | ˨˦ (24) | rising |

In addition to these tones, there is also a neutral tone.[13]

Tone sandhi

editAs with other dialects of Hokkien, the tone sandhi rules are applied to every syllable but the final syllable in an utterance. The following is a summary of the rules:[21]

- The yin level (33) and yang rising (22) tones do not undergo tone sandhi.

- The yang level and entering tones (24) are pronounced as the yang rising tone (22).

- The yin rising tone (554) is pronounced as the yang level tone (24).

- The departing tone (41) depends on the voicing of the initial consonant in Middle Chinese:

- If the Middle Chinese initial consonant is voiceless, it is pronounced as the yin rising tone (554).

- If the Middle Chinese initial consonant is voiced, it is pronounced as the yang rising tone (22).

- The yin entering (5) depends on the final consonant:

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Lin 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Mei, Tsu-lin (1970), "Tones and prosody in Middle Chinese and the origin of the rising tone", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 30: 86–110, doi:10.2307/2718766, JSTOR 2718766

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1984), Middle Chinese: A study in Historical Phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, p. 3, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2023-07-10). "Glottolog 4.8 - Min". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7398962. Archived from the original on 2023-10-13. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ^ Douglas 1873, p. xvii.

- ^ Zhou 2012, p. 111.

- ^ Huang 1998, p. 99.

- ^ Ding 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Cheng 1999, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Quanzhou City Local Chronicles Editorial Board 2000, overview.

- ^ Lin 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Huang 1998, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f Quanzhou City Local Chronicles Editorial Board 2000, ch. 1, sec. 1.

- ^ a b c Zhou 2006, introduction, p. 15.

- ^ Du 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Douglas 1873, p. 610.

- ^ Van der Loon, Piet (1967). "The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies, Part 2" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series. 13: 113.

- ^ Zhou 2006, introduction, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Lin 2008, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Zhou 2006, introduction, p. 17.

- ^ Quanzhou City Local Chronicles Editorial Board 2000, ch. 1, sec. 2.

Sources

edit- Cheng, Chin-Chuan (1999). "Quantitative Studies in Min Dialects". In Ting, Pang-Hsin (ed.). Contemporary Studies in Min Dialects. Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series. Vol. 14. Chinese University Press, Project on Linguistic Analysis. pp. 229–246. JSTOR 23833469.

- Ding, Picus Sizhi (2016). Southern Min (Hokkien) as a Migrating Language: A Comparative Study of Language Shift and Maintenance Across National Borders. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 978-981-287-594-5.

- Douglas, Rev. Carstairs (1873). Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy, with the Principal Variations of the Chang-chew and Chin-chew dialects. London: Trübner & Co.

- Du, Xiao-ping (2013). 从《厦英大辞典》看泉州方言语音100多年来的演变 [The Phonetic Changes of Quanzhou Dialect in the Recent 100 Years from the Perspective of Chinese–English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy]. Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy & Social Sciences) (in Chinese) (4): 141–145.

- Huang, Diancheng, ed. (1998). 福建省志·方言志 (in Chinese). Beijing: 方言出版社. ISBN 7-80122-279-2. Archived from the original on 2019-02-10. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- Lin, Huadong (2008). 泉州方言研究 (in Chinese). Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. ISBN 9787561530030.

- Quanzhou City Local Chronicles Editorial Board, ed. (2000). 泉州市志 [Quanzhou Annals] (in Chinese). Vol. 50: 方言. Beijing: China Society Science Publishing House. ISBN 7-5004-2700-X.

- Zhou, Changji [in Chinese], ed. (2006). 闽南方言大词典 (in Chinese). Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House. ISBN 7-211-03896-9.

- Zhou, Changji (2012). B1—15、16 闽语. 中国语言地图集 [Language Atlas of China] (in Chinese). Vol. 汉语方言卷 (2nd ed.). Beijing: Commercial Press. pp. 110–115. ISBN 978-7-100-07054-6.

External links

edit- 當代泉州音字彙, a dictionary of Quanzhou speech