The pyramid of Khui is an ancient Egyptian funerary structure datable to the early First Intermediate Period (2181 BC – 2055 BC) and located in the royal necropolis of Dara, near Manfalut in Middle Egypt and close to the entrance of the Dakhla Oasis.[1] It is generally attributed to Khui, a kinglet belonging either to the 8th Dynasty or a provincial nomarch proclaiming himself king in a time when central authority had broken down, c. 2150 BC. The pyramid complex of Khui included a mortuary temple and a mud brick enclosure wall which, like the main pyramid, are now completely ruined.

| Pyramid of Khui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Khui (unproven) | |

| Coordinates | 27°18′28″N 30°52′18″E / 27.30778°N 30.87167°E |

| Constructed | First Intermediate Period |

| Type | Step pyramid or mastaba |

| Height | n.d. |

| Base | 146 metres (479 ft) (larger) 136 metres (446 ft) (smaller) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Excavations

editHistory of research

editThe ruined pyramid was first mentioned in a 1912 article of the Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte by the Egyptian Egyptologist Ahmed Kamal.[2] Later, between 1946 and 1948, the complex was explored by Raymond Weill.[3] Due both to the ruined state of the structure and to the building's atypical architecture, Kamal believed it to be a huge mastaba while Weill thought it was a pyramid. Even today, in spite of the fact that the building is commonly considered to be a pyramid—and possibly a step pyramid—it is not possible to determine with certainty which type of tomb it was, and one cannot exclude that it was indeed a mastaba.[1][4]

Attribution

editNo name of the owner was found on the pyramid site; however excavations of a tomb located immediately south of the pyramid yielded a stone block with a relief bearing the cartouche ḫwj , that is Khui, the nomen of an hitherto unknown pharaoh. The block could come from the mortuary temple of the pyramid complex, traces of which may have been discovered North of the pyramid.[5] However, the identification of Khui as the owner of the complex, although commonly accepted, is still unproven.[1]

Main structure

editThe remains of the structure today looks similar to the first step of a step pyramid however, as pointed out above, it remains impossible to ascert that the structure was a pyramid. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the structure was completed or not.

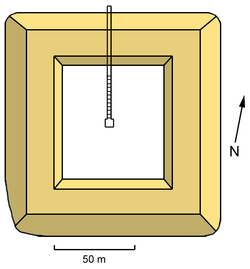

The ground plan of the main structure is rectangular and measures 146 metres (479 ft) x 136 metres (446 ft). The mudbrick walls of the pyramid are slanted inwards and are up to 35 metres (115 ft) thick. This large shell, whose corners are rounded with a radius of curvature of 23 metres (75 ft), surrounds an empty inner space which was probably filled by sand and gravel.[4][5]

Considering these values, if the building really was a step pyramid, it would have had a base larger than that of the famous Step Pyramid of Djoser,[1] while in the case of a mastaba, it would have exceeded in size the already considerable Mastabet el-Fara'un of Shepseskaf.

Hypogeum

editFrom the North face of the structure, an horizontal corridor, whose entrance is at ground level, goes straight into the center of the structure. The corridor then continues to a descending gallery, lined with limestone, topped by eleven arches and reinforced with pilasters.[1] The gallery finally leads to the burial chamber, placed in the center of the building's base.[1]

The rectangular burial chamber is located 8.8 metres (29 ft) meters under the ground level and measures 3.5 metres (11 ft) x 7 metres (23 ft). Its walls are made of roughly worked limestone blocks, presumably taken from a nearby, older necropolis of the 6th Dynasty.

The hypogeum was found completely empty during the excavations and was certainly robbed and nearly destroyed in antiquity. Consequently, it is impossible to say if anybody had indeed been buried here. The structure of the burial chamber bears many similarities with that of Mastaba K1 of Beit Khallaf, dating back to the 3rd Dynasty.[4]

Funerary complex

editOn the North side of the main structure, the ruined remains of a building were found, which may belong to a mortuary temple originally part of the pyramid complex. However, the remains are not sufficient to obtain a reliable reconstruction of the temple. Remains of a portion of a perimeter wall of mudbricks were also found, but they run in an area that is now under the modern village of Dara.[5]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids, London, 2008, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3, p. 164 ff.

- ^ Kamal, Ahmed Bey (1912). "Fouilles à Dara et à Qoçéîr el-Amarna". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. p. 132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Raymond Weill: Dara. Campagne de 1946-1948, Cairo, 1958.

- ^ a b c Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1997, pp. 416–417 - ISBN 3-499-60890-1

- ^ a b c "Egyptian kings Mentuhotep, Antef, Intef, Mentuhotpe". www.nemo.nu. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

Bibliography

edit- Ahmed Fakhry: The Pyramids. 1961 und 1969, pp. 202–204 - ISBN 0-226-23473-8

- Mark Lehner: Geheimnis der Pyramiden, ECON-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1997. ISBN 3-572-01039-X.

- Rainer Stadelmann: Die ägyptischen Pyramiden. Zabern Verlag, Mainz 1991, pp. 229–230, Abb. 73 - ISBN 3-8053-1142-7

- Theis, Christoffer: Die Pyramiden der Ersten Zwischenzeit. Nach philologischen und archäologischen Quellen. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, Bd. 39, 2010, pp. 321–339.