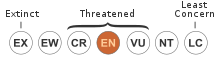

The Puerto Rican nightjar, Puerto Rican whip-poor-will or guabairo (Antrostomus noctitherus) is a bird in the nightjar family found in the coastal dry scrub forests in localized areas of southwestern Puerto Rico. It was described in 1916 from bones found in a cave in north central Puerto Rico and a single skin specimen from 1888, and was considered extinct until observed in the wild in 1961. The current population is estimated as 1,400-2,000 mature birds. The species is currently classified as Endangered due to pressures from habitat loss.

| Puerto Rican nightjar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Strisores |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes |

| Family: | Caprimulgidae |

| Genus: | Antrostomus |

| Species: | A. noctitherus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Antrostomus noctitherus (Wetmore, 1919)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Caprimulgus noctitherus (Wetmore, 1919) | |

Description

editPuerto Rican nightjars, whose song is composed of rapid "whip" notes, are small birds about 22–23 cm in length, weighing 39–41 g. Similar to the Antillean nighthawk, the species has a mottled, black, brown and gray colored plumage which serves as camouflage while the bird is perched on the ground. Males have a black throat with a white thin horizontal line. There are white spots on the lower part of the tail which are visible in flight. Females are of a buff rather than white coloration. Puerto Rican nightjars have large, dark black eyes, a short gray bill, and gray tarsi. Like all nightjars, they possess stiff bristles around the beak to help with the capture of insects in flight.[2][3]

History

editThe Puerto Rican nightjar was first discovered as a single skin specimen found in the Northern part of Puerto Rico in 1888, and rediscovered and correctly identified in 1916 when bones were discovered in a cave in northern Puerto Rico. The species was originally considered already extinct at the time of its discovery. Confirmation of living specimens only occurred in 1961 in the Guánica Dry Forest.[2][3][4] Detailed studies of the species started in 1969.[3][5]

Distribution and habitat

editThe species is likely to have historically occurred in moist limestone and coastal forests in northern Puerto Rico, in addition to the current range of dry limestone, lower cordillera and dry coastal forest. The nightjar is presently mostly found in closed canopy dry forest on limestone soils with abundant leaf litter and an open understorey. Lower densities are present in open scrubby forests.[1] Populations have so far been confirmed in three locations in the southwest of the island: Susúa State Forest, Guánica Dry Forest and Guayanilla Hills.[3][5] The first nesting record of the Puerto Rican nightjar in Maricao State Forest was reported in 2005.[6]

Ecology

editThe Puerto Rican nightjar feeds on beetles, moths and other insects that it catches in flight.[1] It nests on the ground under closed canopies and needs an abundant leaf layer to hold the eggs.[3][7] The peak months for nesting activity are April–June.[7] The clutch is usually of 1–2 eggs, which are light brown with darker brown or purple patches.[3] The eggs have an incubation period of 18–20 days and are primarily incubated by the male.[3][6] The chicks are a cinnamon downy color[6] and they start to fly at about 14 days after hatching.[3] Like many ground-nesting birds, the nightjar will try to divert the attention of potential predators away from the nest by conspicuously flying away and vibrating its wings.[3] The species may be permanently territorial.[1]

Conservation status

editEstimates of the breeding population of Puerto Rican nightjars in 1962 were of less than 100 pairs.[5] In 1968, the species was added to the endangered species list of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the IUCN Red List, where it was originally classified as Threatened.[5][8] It was uplisted to Critically Endangered in 1994, but downlisted again to Endangered in 2011, after the population had been assessed as small but essentially stable. Current estimates are of 1,400-2000 mature birds, which roughly corresponds to 1984 numbers. The species is legally protected throughout its range.[1]

Puerto Rican nightjars are considered to be under pressure from habitat loss due to urban development and agricultural expansion, and through predation by introduced predators such as the small Indian mongoose and feral cats, and native predators such as owls.[1][3] It is possible that the large scale deforestation that occurred during the late 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s is the reason that the nightjars are no longer found on the north part of the island.[5][7]

Mitigating habitat impact on private lands and controlling public access to the forest reserves during their peak nesting season has been suggested as a conservation management technique for this species.[7]

Gallery

edit-

Adult and chick

-

Facial features

-

In habitat

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f BirdLife International (2012). "Antrostomus noctitherus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T22689809A40430002. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22689809A40430002.en.

- ^ a b "Distribution - Puerto Rican Nightjar (Antrostomus noctitherus) - Neotropical Birds". neotropical.birds.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Oberle, Mark W. (2010). Puerto Rico's Birds in Photographs. Seattle, Washington: Editorial Humanitas. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-9650104-5-0.

- ^ Gonzalez, Rafael Gonzalez (2010-01-01). Population estimation and landscape ecology of the Puerto Rican Nightjar (Thesis). United States -- Mississippi: Mississippi State University. ProQuest 250282747.

- ^ a b c d e Vilella, Francisco J.; Zwank, Philip J. (1993-01-01). "Geographic Distribution and Abundance of the Puerto Rican Nightjar (Distribución Geográfica y Abundancia del Guabairo Pequeño de Puerto Rico (Caprimulgus noctitherus)". Journal of Field Ornithology. 64 (2): 223–238. JSTOR 4513803.

- ^ a b c Delannoy, Carlos A. (2005). "First nesting records of the Puerto Rican Nightjar and Antillean Nighthawk in a montane forest of western Puerto Rico". Journal of Field Ornithology. 76 (3): 271–273. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-76.3.271. S2CID 86200945.

- ^ a b c d Vilella, Francisco J. (2008-12-01). "Nest habitat use of the Puerto Rican Nightjar Caprimulgus noctitherus in Guánica Biosphere Reserve". Bird Conservation International. 18 (4): 307–317. doi:10.1017/S0959270908007594. ISSN 1474-0001.

- ^ Vilella, Francisco J. (1995-09-01). "Reproductive ecology and behaviour of the Puerto Rican Nightjar Caprimulgus noctitherus". Bird Conservation International. 5 (2–3): 349–366. doi:10.1017/S095927090000109X. ISSN 1474-0001.