Prochlorococcus is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation (chlorophyll a2 and b2). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosynthetic organism on Earth. Prochlorococcus microbes are among the major primary producers in the ocean, responsible for a large percentage of the photosynthetic production of oxygen.[1][2] Prochlorococcus strains, called ecotypes, have physiological differences enabling them to exploit different ecological niches.[3] Analysis of the genome sequences of Prochlorococcus strains show that 1,273[4] genes are common to all strains, and the average genome size is about 2,000 genes.[1] In contrast, eukaryotic algae have over 10,000 genes.[4]

| Prochlorococcus | |

|---|---|

| |

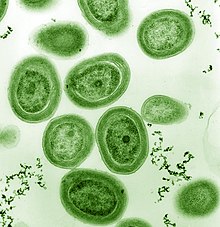

| TEM image of Prochlorococcus marinus (pseudo-colored) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Cyanobacteria |

| Class: | Cyanophyceae |

| Order: | Synechococcales |

| Family: | Prochloraceae |

| Genus: | Prochlorococcus Chisholm et al., 1992 |

| Species: | P. marinus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Prochlorococcus marinus Chisholm et al., 1992

| |

Discovery

editAlthough there had been several earlier records of very small chlorophyll-b-containing cyanobacteria in the ocean,[5][6] Prochlorococcus was discovered in 1986[7] by Sallie W. (Penny) Chisholm of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Robert J. Olson of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and other collaborators in the Sargasso Sea using flow cytometry. Chisholm was awarded the Crafoord Prize in 2019 for the discovery.[8] The first culture of Prochlorococcus was isolated in the Sargasso Sea in 1988 (strain SS120) and shortly another strain was obtained from the Mediterranean Sea (strain MED). The name Prochlorococcus[9] originated from the fact it was originally assumed that Prochlorococcus was related to Prochloron and other chlorophyll-b-containing bacteria, called prochlorophytes, but it is now known that prochlorophytes form several separate phylogenetic groups within the cyanobacteria subgroup of the bacteria domain. The only species within the genus described is Prochlorococcus marinus, although two subspecies have been named for low-light and high-light adapted niche variations.[10]

Morphology

editMarine cyanobacteria are to date the smallest known photosynthetic organisms; Prochlorococcus is the smallest at just 0.5 to 0.7 micrometres in diameter.[11][2] The coccoid shaped cells are non-motile and free-living. Their small size and large surface-area-to-volume ratio, gives them an advantage in nutrient-poor water. Still, it is assumed that Prochlorococcus have a very small nutrient requirement.[12] Moreover, Prochlorococcus have adapted to use sulfolipids instead of phospholipids in their membranes to survive in phosphate deprived environments.[13] This adaptation allows them to avoid competition with heterotrophs that are dependent on phosphate for survival.[13] Typically, Prochlorococcus divide once a day in the subsurface layer or oligotrophic waters.[12]

Distribution

editProchlorococcus is abundant in the euphotic zone of the world's tropical oceans.[14] It is possibly the most plentiful genus on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater may contain 100,000 cells or more. Worldwide, the average yearly abundance is (2.8 to 3.0)×1027 individuals[15] (for comparison, that is approximately the number of atoms in a ton of gold). Prochlorococcus is ubiquitous between 40°N and 40°S and dominates in the oligotrophic (nutrient-poor) regions of the oceans.[12] Prochlorococcus is mostly found in a temperature range of 10–33 °C and some strains can grow at depths with low light (<1% surface light).[1] These strains are known as LL (Low Light) ecotypes, with strains that occupy shallower depths in the water column known as HL (High Light) ecotypes.[16] Furthermore, Prochlorococcus are more plentiful in the presence of heterotrophs that have catalase abilities.[17] Prochlorococcus do not have mechanisms to degrade reactive oxygen species and rely on heterotrophs to protect them.[17] The bacterium accounts for an estimated 13–48% of the global photosynthetic production of oxygen, and forms part of the base of the ocean food chain.[18]

Pigments

editProchlorococcus is closely related to Synechococcus, another abundant photosynthetic cyanobacteria, which contains the light-harvesting antennae phycobilisomes. However, Prochlorochoccus has evolved to use a unique light-harvesting complex, consisting predominantly of divinyl derivatives of chlorophyll a (Chl a2) and chlorophyll b (Chl b2) and lacking monovinyl chlorophylls and phycobilisomes.[19] Prochlorococcus is the only known wild-type oxygenic phototroph that does not contain Chl a as a major photosynthetic pigment, and is the only known prokaryote with α-carotene.[20]

Genome

editThe genomes of several strains of Prochlorococcus have been sequenced.[21][22] Twelve complete genomes have been sequenced which reveal physiologically and genetically distinct lineages of Prochlorococcus marinus that are 97% similar in the 16S rRNA gene.[23] Research has shown that a massive genome reduction occurred during the Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth, which was followed by population bottlenecks.[24]

The high-light ecotype has the smallest genome (1,657,990 basepairs, 1,716 genes) of any known oxygenic phototroph, but the genome of the low-light type is much larger (2,410,873 base pairs, 2,275 genes).[21]

DNA recombination, repair and replication

editMarine Prochlorococcus cyanobacteria have several genes that function in DNA recombination, repair and replication. These include the recBCD gene complex whose product, exonuclease V, functions in recombinational repair of DNA, and the umuCD gene complex whose product, DNA polymerase V, functions in error-prone DNA replication.[25] These cyanobacteria also have the gene lexA that regulates an SOS response system, probably a system like the well-studied E. coli SOS system that is employed in the response to DNA damage.[25]

Ecology

editAncestors of Prochlorococcus contributed to the production of early atmospheric oxygen.[26] Despite Prochlorococcus being one of the smallest types of marine phytoplankton in the world's oceans, its substantial number make it responsible for a major part of the oceans', world's photosynthesis, and oxygen production.[2] The size of Prochlorococcus (0.5 to 0.7 μm)[12] and the adaptations of the various ecotypes allow the organism to grow abundantly in low nutrient waters such as the waters of the tropics and the subtropics (c. 40°N to 40°S);[27] however, they can be found in higher latitudes as high up as 60° north but at fairly minimal concentrations and the bacteria's distribution across the oceans suggest that the colder waters could be fatal. This wide range of latitude along with the bacteria's ability to survive up to depths of 100 to 150 metres, i.e. the average depth of the mixing layer of the surface ocean, allows it to grow to enormous numbers, up to 3×1027 individuals worldwide.[15] This enormous number makes the Prochlorococcus play an important role in the global carbon cycle and oxygen production. Along with Synechococcus (another genus of cyanobacteria that co-occurs with Prochlorococcus) these cyanobacteria are responsible for approximately 50% of marine carbon fixation, making it an important carbon sink via the biological carbon pump (i.e. the transfer of organic carbon from the surface ocean to the deep via several biological, physical and chemical processes).[28] The abundance, distribution and all other characteristics of the Prochlorococcus make it a key organism in oligotrophic waters serving as an important primary producer to the open ocean food webs.

Ecotypes

editProchlorococcus has different "ecotypes" occupying different niches and can vary by pigments, light requirements, nitrogen and phosphorus utilization, copper, and virus sensitivity.[29][11][21] It is thought that Prochlorococcus may occupy potentially 35 different ecotypes and sub-ecotypes within the worlds' oceans. They can be differentiated on the basis of the sequence of the ribosomal RNA gene.[11][29] It has been broken down by NCBI Taxonomy into two different subspecies, Low-light Adapted (LL) or High-light Adapted (HL).[10] There are six clades within each subspecies.[11]

Low-light adapted

editProchlorococcus marinus subsp. marinus is associated with low-light adapted types.[10] It is also further classified by sub-ecotypes LLI-LLVII, where LLII/III has not been yet phylogenetically uncoupled.[11][30] LV species are found in highly iron scarce locations around the equator, and as a result, have lost several ferric proteins.[31] The low-light adapted subspecies is otherwise known to have a higher ratio of chlorophyll b2 to chlorophyll a2,[29] which aids in its ability to absorb blue light.[32] Blue light is able to penetrate ocean waters deeper than the rest of the visible spectrum, and can reach depths of >200 m, depending on the turbidity of the water. Their ability to photosynthesize at a depth where blue light penetrates allows them to inhabit depths between 80 and 200 m.[23][33] Their genomes can range from 1,650,000 to 2,600,000 basepairs in size.[30]

High-light adapted

editProchlorococcus marinus subsp. pastoris is associated with high-light adapted types.[10] It can be further classified by sub-ecotypes HLI-HLVI.[30][11] HLIII, like LV, is also located in an iron-limited environment near the equator, with similar ferric adaptations.[31] The high-light adapted subspecies is otherwise known to have a low ratio of chlorophyll b2 to chlorophyll a2.[29] High-light adapted strains inhabit depths between 25 and 100 m.[23] Their genomes can range from 1,640,000 to 1,800,000 basepairs in size.[30]

Metabolism

editMost cyanobacterium are known to have an incomplete tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA).[34][35] In this process, 2-oxoglutarate decarboxylase (2OGDC) and succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH), replace the enzyme 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (2-OGDH).[35] Normally, when this enzyme complex joins with NADP+, it can be converted to succinate from 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG).[35] This pathway is non-functional in Prochlorococcus,[35] as succinate dehydrogenase has been lost evolutionarily to conserve energy that may have otherwise been lost to phosphate metabolism.[36]

Strains

edit| Strain | Subtype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| MIT9515 | HLI | [4] |

| EQPAC1 | HLI | [37] |

| MED4 | HLI | [21] |

| XMU1401 | HLII | [38] |

| MIT0604 | HLII | [37] |

| AS9601 | HLII | [4] |

| GP2 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9107 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9116 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9123 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9201 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9202 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9215 | HLII | [4] |

| MIT9301 | HLII | [4] |

| MIT9302 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9311 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9312 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9314 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9321 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9322 | HLII | [37] |

| MIT9401 | HLII | [37] |

| SB | HLII | [37] |

| XMU1403 | LLI | [39] |

| XMU1408 | LLI | [39] |

| MIT0801 | LLI | [37] |

| NATL1A | LLI | [4] |

| NATL2A | LLI | [4] |

| PAC1 | LLI | [37] |

| LG | LLII/III | [37] |

| MIT0601 | LLII/III | [37] |

| MIT0602 | LLII/III | [37] |

| MIT0603 | LLII/III | [37] |

| MIT9211 | LLII/III | [4] |

| SS35 | LLII/III | [37] |

| SS52 | LLII/III | [37] |

| SS120 | LLII/III | [22] |

| SS2 | LLII/III | [37] |

| SS51 | LLII/III | [37] |

| MIT0701 | LLIV | [37] |

| MIT0702 | LLIV | [37] |

| MIT0703 | LLIV | [37] |

| MIT9303 | LLIV | [4] |

| MIT9313 | LLIV | [4] |

| MIT1303 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1306 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1312 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1313 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1318 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1320 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1323 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1327 | LLIV | [40] |

| MIT1342 | LLIV | [40] |

Table modified from [30]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Munn, C. (2011). Marine Microbiology: Ecology and applications (2nd ed.). Garland Science.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Chimileski, Scott; Kolter, Roberto (25 September 2017). Life at the Edge of Sight. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97591-0. Retrieved 2018-01-26.[page needed]

- ^ Tolonen AC, Aach J, Lindell D, Johnson ZI, Rector T, Steen R, Church GM, Chisholm SW (October 2006). "Global gene expression of Prochlorococcus ecotypes in response to changes in nitrogen availability". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (1). 53. doi:10.1038/msb4100087. PMC 1682016. PMID 17016519.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kettler GC, Martiny AC, Huang K, et al. (December 2007). "Patterns and Implications of Gene Gain and Loss in the Evolution of Prochlorococcus". PLoS Genetics. 3 (12). e231. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231. PMC 2151091. PMID 18159947.

- ^ Johnson, P.W.; Sieburth, J.M. (1979). "Chroococcoid cyanobacteria in the sea: a ubiquitous and diverse phototrophic biomass". Limnology and Oceanography. 24 (5): 928–935. Bibcode:1979LimOc..24..928J. doi:10.4319/lo.1979.24.5.0928.

- ^ Gieskes, W.W.C.; Kraay, G.W. (1983). "Unknown chlorophyll a derivatives in the North Sea and the tropical Atlantic Ocean revealed by HPLC analysis". Limnology and Oceanography. 28 (4): 757–766. Bibcode:1983LimOc..28..757G. doi:10.4319/lo.1983.28.4.0757.

- ^ Chisholm, S.W.; Olson, R.J.; Zettler, E.R.; Waterbury, J.; Goericke, R.; Welschmeyer, N. (1988). "A novel free-living prochlorophyte occurs at high cell concentrations in the oceanic euphotic zone". Nature. 334 (6180): 340–3. Bibcode:1988Natur.334..340C. doi:10.1038/334340a0. S2CID 4373102.

- ^ "The Crafoord Prize in Biosciences 2019". Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. January 17, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Chisholm, S.W.; Frankel, S.L.; Goericke, R.; Olson, R.J.; Palenik, B.; Waterbury, J.B.; West-Johnsrud, L.; Zettler, E.R. (1992). "Prochlorococcus marinus nov. gen. nov. sp.: an oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll a and b". Archives of Microbiology. 157 (3): 297–300. Bibcode:1992ArMic.157..297C. doi:10.1007/BF00245165. S2CID 32682912.

- ^ a b c d "Prochlorococcus marinus". NCBI. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f Biller, Steven J.; Berube, Paul M.; Lindell, Debbie; Chisholm, Sallie W. (1 December 2014). "Prochlorococcus: the structure and function of collective diversity" (PDF). Nature Reviews Microbiology. 13 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3378. hdl:1721.1/97151. PMID 25435307. S2CID 18963108.

- ^ a b c d Partensky F, Hess WR, Vaulot D (1999). "Prochlorococcus, a marine photosynthetic prokaryote of global significance". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 63 (1): 106–127. doi:10.1128/MMBR.63.1.106-127.1999. PMC 98958. PMID 10066832.

- ^ a b Van Mooy, B. A. S.; Rocap, G.; Fredricks, H. F.; Evans, C. T.; Devol, A. H. (26 May 2006). "Sulfolipids dramatically decrease phosphorus demand by picocyanobacteria in oligotrophic marine environments". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (23): 8607–12. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.8607V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600540103. PMC 1482627. PMID 16731626.

- ^ Chisholm, S.W.; Frankel, S.; Goericke, R.; Olson, R.; Palenik, B.; Waterbury, J.; West-Johnsrud, L.; Zettler, E. (1992). "Prochlorococcus marinus nov. gen. nov. sp.: an oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll a and b.". Archives of Microbiology. 157 (3): 297–300. Bibcode:1992ArMic.157..297C. doi:10.1007/bf00245165. S2CID 32682912.

- ^ a b Flombaum, P.; Gallegos, J. L.; Gordillo, R. A.; Rincon, J.; Zabala, L. L.; Jiao, N.; Karl, D. M.; Li, W. K. W.; Lomas, M. W.; Veneziano, D.; Vera, C. S.; Vrugt, J. A.; Martiny, A. C. (2013). "Present and future global distributions of the marine Cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (24): 9824–9. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.9824F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307701110. PMC 3683724. PMID 23703908.

- ^ Coleman, M.; Sullivan, M.; Martiny, A.; Steglich, C.; Barry, K.; DeLong, E.; Chisholm, S. (2006). "Genomic islands and the ecology and evolution of Prochlorococcus". Science. 311 (5768): 1768–70. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1768C. doi:10.1126/science.1122050. PMID 16556843. S2CID 3196592.

- ^ a b Morris, J. J.; Kirkegaard, R.; Szul, M. J.; Johnson, Z. I.; Zinser, E. R. (23 May 2008). "Facilitation of Robust Growth of Prochlorococcus Colonies and Dilute Liquid Cultures by "Helper" Heterotrophic Bacteria". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 74 (14): 4530–4. Bibcode:2008ApEnM..74.4530M. doi:10.1128/AEM.02479-07. PMC 2493173. PMID 18502916.

- ^ Johnson, Zachary I.; Zinser, Erik R.; Coe, Allison; McNulty, Nathan P.; Woodward, E. Malcolm S.; Chisholm, Sallie W. (2006). "Niche Partitioning among Prochlorococcus Ecotypes along Ocean-Scale Environmental Gradients". Science. 311 (5768): 1737–40. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1737J. doi:10.1126/science.1118052. PMID 16556835. S2CID 3549275.

- ^ Ting CS, Rocap G, King J, Chisholm S (2002). "Cyanobacterial photosynthesis in the oceans: the origins and significance of divergent light-harvesting strategies". Trends in Microbiology. 10 (3): 134–142. doi:10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02319-3. PMID 11864823.

- ^ Goericke R, Repeta D (1992). "The pigments of Prochlorococcus marinus: the presence of divinyl chlorophyll a and b in a marine prokaryote". Limnology and Oceanography. 37 (2): 425–433. Bibcode:1992LimOc..37..425R. doi:10.4319/lo.1992.37.2.0425.

- ^ a b c d G. Rocap, G.; Larimer, F.W.; Lamerdin, J.; Malfatti, S.; Chain, P.; Ahlgren, N.A.; Arellano, A.; Coleman, M.; Hauser, L.; Hess, W.R.; Johnson, Z.I.; Land, M.; Lindell, D.; Post, A.F.; Regala, W.; Shah, M.; Shaw, S.L.; Steglich, C.; Sullivan, M.B.; Ting, C.S.; Tolonen, A.; Webb, E.A.; Zinser, E.R.; Chisholm, S.W. (2003). "Genome divergence in two Prochlorococcus ecotypes reflects oceanic niche differentiation". Nature. 424 (6952): 1042–7. Bibcode:2003Natur.424.1042R. doi:10.1038/nature01947. PMID 12917642. S2CID 4344597.

- ^ a b Dufresne, Alexis; Salanoubat, Marcel; Partensky, Frédéric; Artiguenave, François; Axmann, Ilka M.; Barbe, Valérie; Duprat, Simone; Galperin, Michael Y.; Koonin, Eugene V.; Le Gall, Florence; Makarova, Kira S. (2003-08-19). "Genome sequence of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus SS120, a nearly minimal oxyphototrophic genome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (17): 10020–5. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10010020D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1733211100. PMC 187748. PMID 12917486.

- ^ a b c Martiny AC, Tai A, Veneziano D, Primeau F, Chisholm S (2009). "Taxonomic resolution, ecotypes and biogeography of Prochlorococcus". Environmental Microbiology. 11 (4): 823–832. Bibcode:2009EnvMi..11..823M. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01803.x. PMID 19021692. S2CID 25323390.

- ^ Zhang, H.; Hellweger, F. L.; Luo, H. (2024). "Genome reduction occurred in early Prochlorococcus with an unusually low effective population size". The ISME Journal. 18 (1): wrad035. doi:10.1093/ismejo/wrad035. PMC 10837832. PMID 38365237.

- ^ a b Cassier-Chauvat C, Veaudor T, Chauvat F (2016). "Comparative Genomics of DNA Recombination and Repair in Cyanobacteria: Biotechnological Implications". Front Microbiol. 7: 1809. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01809. PMC 5101192. PMID 27881980.

- ^ The tiny creature that secretly powers the planet | Penny Chisholm, retrieved 2022-04-26

- ^ Partensky, F.; Blanchot, J.; Vaulot, D. (1999). "Differential distribution and ecology of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus in oceanic waters: a review". Bulletin de l'Institut Océanographique de Monaco (spécial 19): 431. ISSN 0304-5722.

- ^ Fu, Fei-Xue; Warner, Mark E.; Zhang, Yaohong; Feng, Yuanyuan; Hutchins, David A. (16 May 2007). "Effects of Increased Temperature and CO2 on Photosynthesis, Growth, and Elemental Ratios in Marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (Cyanobacteria)". Journal of Phycology. 43 (3): 485–496. Bibcode:2007JPcgy..43..485F. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00355.x. S2CID 53353243.

- ^ a b c d West, N.J.; Scanlan, D.J. (1999). "Niche-partitioning of Prochlorococcus in a stratified water column in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 65 (6): 2585–91. doi:10.1128/AEM.65.6.2585-2591.1999. PMC 91382. PMID 10347047.

- ^ a b c d e Yan, Wei; Feng, Xuejin; Zhang, Wei; Zhang, Rui; Jiao, Nianzhi (2020-11-01). "Research advances on ecotype and sub-ecotype differentiation of Prochlorococcus and its environmental adaptability". Science China Earth Sciences. 63 (11): 1691–1700. Bibcode:2020ScChD..63.1691Y. doi:10.1007/s11430-020-9651-0. ISSN 1869-1897. S2CID 221218462.

- ^ a b Rusch, Douglas B.; Martiny, Adam C.; Dupont, Christopher L.; Halpern, Aaron L.; Venter, J. Craig (2010-09-14). "Characterization of Prochlorococcus clades from iron-depleted oceanic regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (37): 16184–9. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716184R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009513107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2941326. PMID 20733077.

- ^ Ralf, G.; Repeta, D. (1992). "The pigments of Prochlorococcus marinus: The presence of divinylchlorophyll a and b in a marine prokaryote". Limnology and Oceanography. 37 (2): 425–433. Bibcode:1992LimOc..37..425R. doi:10.4319/lo.1992.37.2.0425.

- ^ Zinser, E.; Johnson, Z.; Coe, A.; Karaca, E.; Veneziano, D.; Chisholm, S. (2007). "Influence of light and temperature on Prochlorococcus ecotype distributions in the Atlantic Ocean". Limnology and Oceanography. 52 (5): 2205–20. Bibcode:2007LimOc..52.2205Z. doi:10.4319/lo.2007.52.5.2205. S2CID 84767930.

- ^ García-Fernández, Jose M.; Diez, Jesús (December 2004). "Adaptive mechanisms of nitrogen and carbon assimilatory pathways in the marine cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus". Research in Microbiology. 155 (10): 795–802. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2004.06.009. ISSN 0923-2508. PMID 15567272.

- ^ a b c d Zhang, Shuyi; Bryant, Donald A. (2011-12-16). "The Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle in Cyanobacteria". Science. 334 (6062): 1551–3. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1551Z. doi:10.1126/science.1210858. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22174252. S2CID 206536295.

- ^ Casey, John R.; Mardinoglu, Adil; Nielsen, Jens; Karl, David M. (2016-12-27). Gutierrez, Marcelino (ed.). "Adaptive Evolution of Phosphorus Metabolism in Prochlorococcus". mSystems. 1 (6): e00065–16. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00065-16. ISSN 2379-5077. PMC 5111396. PMID 27868089.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Biller, Steven J.; Berube, Paul M.; Berta-Thompson, Jessie W.; Kelly, Libusha; Roggensack, Sara E.; Awad, Lana; Roache-Johnson, Kathryn H.; Ding, Huiming; Giovannoni, Stephen J.; Rocap, Gabrielle; Moore, Lisa R. (2014-09-30). "Genomes of diverse isolates of the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus". Scientific Data. 1 (1): 140034. doi:10.1038/sdata.2014.34. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 4421930. PMID 25977791.

- ^ Yan, Wei; Zhang, Rui; Wei, Shuzhen; Zeng, Qinglu; Xiao, Xilin; Wang, Qiong; Yan, Hanrui; Jiao, Nianzhi (2018-01-11). "Draft Genome Sequence of Prochlorococcus marinus Strain XMU1401, Isolated from the Western Tropical North Pacific Ocean". Genome Announcements. 6 (2): e01431–17. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01431-17. ISSN 2169-8287. PMC 5764940. PMID 29326216.

- ^ a b Yan, Wei; Wei, Shuzhen; Wang, Qiong; Xiao, Xilin; Zeng, Qinglu; Jiao, Nianzhi; Zhang, Rui (September 2018). "Genome Rearrangement Shapes Prochlorococcus Ecological Adaptation". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 84 (17): e01178–18. Bibcode:2018ApEnM..84E1178Y. doi:10.1128/AEM.01178-18. PMC 6102989. PMID 29915114.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cubillos-Ruiz, Andres; Berta-Thompson, Jessie W.; Becker, Jamie W.; van der Donk, Wilfred A.; Chisholm, Sallie W. (2017-07-03). "Evolutionary radiation of lanthipeptides in marine cyanobacteria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (27): E5424–33. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E5424C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1700990114. PMC 5502607. PMID 28630351.

Further reading

edit- Campbell, L.; Nolla, H.A.; Vaulot, D. (1994). "The importance of Prochlorococcus to community structure in the central North Pacific Ocean". Limnology and Oceanography. 39 (4): 954–961. Bibcode:1994LimOc..39..954C. doi:10.4319/lo.1994.39.4.0954.

- Pandhal, Jagroop; Wright, Phillip C.; Biggs, Catherine A. (2007). "A quantitative proteomic analysis of light adaptation in a globally significant marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus MED4". Journal of Proteome Research. 6 (3): 996–1005. doi:10.1021/pr060460c. PMID 17298086.

- Nadis, Steve (2003). "The cells that rule the seas: the ocean's tiniest inhabitants, notes biological researcher Sallie W. Chisholm, hold the key to understanding the biosphere — and what happens when humans disrupt it". Scientific American: 52–53. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1203-52. PMID 14631732.

- Garren, Melissa (2012). "The sea we've hardly seen". TEDx Monterey: 52f. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

External links

edit- The Most Important Microbe You've Never Heard Of: NPR Story on Prochlorococcus