Powwow Highway is a Native American 1989 independent[1] comedy-drama film from George Harrison's HandMade Films Company, directed by Jonathan Wacks. Based on the novel Powwow Highway by David Seals, it features A Martinez, Gary Farmer, Joanelle Romero and Amanda Wyss. Wes Studi and Graham Greene, who were relatively unknown actors at the time, have small supporting roles.

| Powwow Highway | |

|---|---|

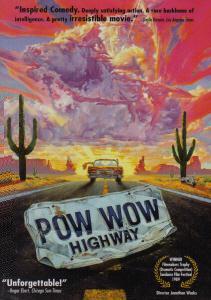

DVD cover art | |

| Directed by | Jonathan Wacks |

| Written by | David Seals Janet Heaney Jean Stawarz |

| Based on | Powwow Highway by David Seals |

| Produced by | Jan Wieringa George Harrison Denis O'Brien |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Toyomichi Kurita |

| Edited by | Jim Stewart |

| Music by | Barry Goldberg |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

editBuddy Red Bow, a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe of Lame Deer, Montana and a quick-tempered activist, is battling greedy developers. On the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, he tries to persuade the council to vote against a strip-mining contract.

Philbert Bono is a hulk of a man guided by sacred visions. He wants to find his medicine and gather tokens from the spirits. During a night at the local bar, he gets inspired by watching a car commercial that advertises to potential customers to find their own "pony". He takes this as a sign, and the next day he visits a junkyard and trades some marijuana to the proprietor to find his "war pony". As he looks outside the window of the junkyard office, he has a vision of several horses running in his direction. He eventually settles on a beat-up and paint-worn 1964 Buick Wildcat, which he names "Protector" as the proprietor tosses him the keys. After a couple of unsuccessful starts, Protector eventually springs to life and he drives off. Throughout his journey, various parts of the car fall off.

Elsewhere, Buddy's estranged sister, Bonnie, is arrested in Santa Fe, New Mexico because of drugs planted in the trunk of her car. Buddy is later contacted and is the only family member who can help Bonnie and her children, Jane and Sky Red Bow. This is eventually revealed as a ploy by the greedy developers trying to pass the strip-mining contract. Without Buddy's presence to vote, they'll have a better chance at succeeding.

Buddy does not own a car but needs to get to his sister. He convinces his childhood acquaintance Philbert to take him to his sister, Philbert happily obliges telling Buddy that they are "Cheyenne". In their childhood, Buddy found Philbert awkward and embarrassing, and Philbert was bullied for being fat. Buddy's attitude towards Philbert has not changed much, but wonders if Philbert remembers how mean he had been to him. Buddy's absence attracts concern that he won't arrive in time, but the tribal chief insists that he will always find a way and that he has done more for the community than anyone else.

They set out on their road trip, and Philbert's easygoing ways contrast with Buddy's more reactive personality. Philbert's frequent stops to pray and eat prove irritating to Buddy, as rather than going directly to Santa Fe, Philbert is motivated by his journey to gather "good medicine" to help them get Bonnie out of prison, even going so far as to take a detour. Along the way they meet with friends in other communities, attend a Pow Wow at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation where Buddy dances with other veterans, and visit the sacred Black Hills in South Dakota where Philbert reverently leaves a giant Hershey's chocolate bar as an offering to his ancestors. Eventually, Buddy joins Philbert in praying and singing to the ancestors in a river. Gradually, the men grow to appreciate and respect one another. Meanwhile, Bonnie has her children contact her best friend, Rabbit, to help pay for the $2000 bail. Unfortunately, it cannot be processed until after the holidays.

When they finally reach Santa Fe, they meet up with Bonnie's friend Rabbit and cause a scene at the precinct. As Rabbit and Buddy interact with the cops, Philbert manages to take $4000 in cash from one of the open rooms. The three eventually regroup at a local area to drink, where Rabbit and Buddy form a minor attraction towards one another. Philbert agrees to fetch Bonnie's kids, who were staying at a nearby hotel and takes them without officially checking out. They head directly to the precinct where Bonnie is being held without telling Buddy and Rabbit, who also try to get there.

The tribal chief has also arrived to talk to Bonnie. Philbert received inspiration from a scene out of an old western during one of their stops and put it to use by breaking Bonnie out of jail by using Protector and a rope to yank the jail bars off the building. As the tribal chief was waiting, he noticed through the window what Philbert had been doing and quietly left the precinct in his truck without telling anyone else. A police chase ensues and Buddy temporarily stays behind to slow down their pursuit by throwing the loose window of Philbert's car at one of the cop cars, causing it to crash. He is soon picked up by Philbert as they continue their escape outside the city. However, Protector loses its brakes on a downhill road, forcing everyone to jump from the car except Philbert who seemingly perishes in the wreck. Seeing the car in flames, the police decide to call off the chase, and backup and leave the scene. After mourning Philbert's death, Buddy, Rabbit, Bonnie, and her kids discover that Philbert survived the crash and they embrace him. Philbert returns Buddy's necklace, and the two join the others as they walk down the highway. Fortunately, the chief of their tribe had been following them after the jailbreak and pulls up with his truck to give them a ride home, presumably to get home in time to vote against the strip-mining contract.

Cast

edit- A Martinez as Buddy Red Bow

- Gary Farmer as Philbert Bono

- Amanda Wyss as Rabbit Layton

- Joanelle Romero as Bonnie Red Bow

- Geoff Rivas as Sandy Youngblood

- Roscoe Born as Agent Jack Novall

- Wayne Waterman as Wolf Tooth

- Margo Kane as Imogene

- Sam Vlahos as Chief Joseph

- John Trudell as Louie Short Hair

- Wes Studi as Buff

- Graham Greene as Vietnam Vet

Production

editFilming was done on location on Native American reservations in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.[2]

Music

editSeveral songs by Robbie Robertson, from his 1987 solo album, accompany scenes in the film.[3]

Reception and legacy

editBox office

editPowwow Highway grossed $283,747 at the North American box office.[4]

Analysis

editThe historian Ryan Driskell Tate has noted that the "film presents political conflicts within Indigenous communities to counter popular caricatures of innate 'Indian-ness'." According to Tate:

Buddy and Philbert spend much of the rising action of the film at odds over their worldviews. Powwow Highway, like most road movies, pairs these same-sex characters together to learn from each other and bond in the journey. Buddy thinks his people’s old stories are inadequate to deal with new political problems...Philbert, on the other hand, believes that the old and new are inseparable, and prizes the survivance of his people. He views the road trip as a “vision quest”—a way to claim the Cheyenne status as a warrior—and mounts his automotive pony horse, his Buick “Protector,” on a tour of sacred spots of Indian culture.[5]

Critical response

editThe character of Philbert Bono was described as a scene-stealer by The New York Times' Janet Maslin, who wrote Philbert is "notable for his tremendous appetite, his unflappably even keel, and his determination to find some kind of spiritual core in contemporary American Indian life."[6] The chemistry between the two leads was also praised.[7][8] In a three-star review, Roger Ebert called Gary Farmer's performance "...one of the most wholly convincing I’ve seen", and added "What Powwow Highway does best is to create two unforgettable characters and give them some time together."[7]

Preservation

editIn 2024, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[9]

Awards

edit- Won

- Sundance Film Festival – Filmmakers Trophy – Dramatic (Jonathan Wacks)[10]

- Native American Film Festival – Best Picture (Jan Wieringa, George Harrison & Denis O'Brien)[2]

- Native American Film Festival – Best Director (Jonathan Wacks)[2]

- Native American Film Festival – Best Actor (A Martinez)[2]

- Nominated

- Sundance Film Festival – Grand Jury Prize (Jonathan Wacks)[10]

- Independent Spirit Awards – Best First Feature (Jan Wieringa, Jonathan Wacks, George Harrison & Denis O'Brien)[11][12]

- Independent Spirit Awards – Best Supporting Male (Gary Farmer)[11]

- Independent Spirit Awards – Best Cinematography (Toyomichi Kurita)[11]

References

edit- ^ DVD Talk

- ^ a b c d "Powwow Highway". AFI|Catalog. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "'Powwow Highway': Actress Amanda Wyss Discusses Films 30th Anniversary And Continued Relevancy". go.Jimmy.go. February 15, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Powwow Highway". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Ryan Driskell Tate, "'This Is the Third World': Coal-Fired America in Montana (1990) and Powwow Highway (1989)," American Energy Cinema, Ed. Robert Lifset, Raechel Lutz, and Sarah Stanford-McIntyre (Morgantown: Univeristy of West Virginia Press, 2023).

- ^ Maslin, Janet (March 24, 1989). "Review/Film; A Cheyenne Mystic Who Transmutes Bitterness". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (April 28, 1989). "Powwow Highway movie review (1989)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Hicks, Chris (September 30, 1989). "Film review: Powwow Highway". Deseret News. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "25 Films Added to National Film Registry for Preservation". December 17, 2024. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "1989 Sundance Film Festival". Sundance.org. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Shuster, Fred (January 22, 1990). "Independent films nominated for awards". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Svirksts, Maris (March 7, 2022). "Native Representation at Film Independent Spirit Awards RNCI Who Tells The Story Matters". Red Nation Celebration Institute. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.