Port Nelson is a ghost town on Hudson Bay, in Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Nelson River. Its peak population in the early 20th century was about 1,000 people.[1] Immediately to the south-southeast is the mouth of the Hayes River and the settlement of York Factory. Some books use 'Port Nelson' to mean the region around the mouths of the two rivers.

History

editEarly history

editPort Nelson was named by Thomas Button who wintered there in 1612.

"August 15, 1612 Captain Thomas Button seeking for a harbour on the west coast of Hudson's Bay in which he might repair damages incurred during a severe storm, discovered the mouth of a large river which he designated Port Nelson, from the name of the master of his ship whom he buried there."[2]

First expedition (1670)

editThe French explorers and fur traders Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers had scouted the area, learning from local native contacts that the Nelson River area had great commercial potential.[3] At the time, much of the focus of early expeditions was on the "bottom of the bay", and a succession of early posts would be established near the bottom of James Bay, starting with Charles Fort (Rupert House) in 1668. This was the closest part of Hudson Bay to New France, and could be reached via inland river routes, as was done during the 1686 French expedition which captured the English posts on James Bay. The Nelson River, meanwhile, provided a route to the western interior of what is now Manitoba.

The devastation of Huronia in the 1640s by the Iroquois during the Beaver Wars had decimated a major ally of the French, the Huron, and weakened their fur trade connections to the interior. This had encouraged Radisson and des Groseilliers to explore further into the interior, with the pair penetrating far into the Pays d'en Haut (the Upper Country, geographically interpreted around the Great Lakes waterways), reaching Lake Superior via inland routes in 1659–1660 and making contact with the Sioux.[4]

Radisson, however, had also set his sights on an expedition via the maritime route to Hudson Bay through the Hudson Strait, and was pursuing English or Dutch financing to do so. The adventurism of Radisson and des Groseilliers had been opposed by the institutional authorities in the colony of New France, leading to their fining and the imprisonment of des Groseilliers following their return from a successful expedition with a fortune in furs—furs which possibly had saved the colony from financial collapse.[4]

This set in motion the Frenchmen's association with mariners from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, including Zachariah Gillam, who captained the Nonsuch on the 1668 expedition with des Groseilliers which led to the establishment of Charles Fort.[4]

The Hudson's Bay Company was formed in 1670. Charles Bayly was appointed as the first overseas governor of the company in May, and by June a new expedition had been dispatched. This consisted of two ships, the Wivenhoe (with Radisson and Bayly aboard) along with the Prince Rupert (captained by Gillam, with des Groseilliers aboard). The convoy reached the western end of the Hudson Strait by August 18, where it split up. The Prince Rupert proceeded successfully to Charles Fort, whilst the Wivenhoe sought the Nelson estuary.[5]

The Wivenhoe struggled with fog and poor winds, and was delayed in finding the Nelson. Eventually, in September, it did so and Bayly was able to go ashore and nail a brass plate of the English royal arms to a tree, thus claiming the territory for England. By this time, however, the local indigenous people had already begun their seasonal migration inland in advance of winter, making it impossible for trading to take place at the estuary. Discouraged, the expedition departed for Charles Fort, having not resulted in even a single seasonal trading operation.[5]

Later expeditions

editA Hudson's Bay Company post was established in 1682 in a context of intense local competition, both from the French Compagnie du Nord (intent on the Hayes River) and from a group of independent New England traders.[6] The New England traders under Benjamin Gillam were focused on the Nelson, but were out-manoeuvred and captured by the French under Pierre-Esprit Radisson.[7]

It was during the period from 1660–1870 – when many Assiniboine and Swampy Cree trappers and hunters became middlemen in the Hudson's Bay Company fur trade economy in Western Canada – that the Cree began to be referred to as "three distinct groups: the Woodland Cree, the Plains Cree, and the Swampy Cree."[8][page needed] The Swampy Cree and the Assiniboine used the Nelson River, along with the Hayes River, as the main inland routes to the great inland lake, Lake Winnipeg.[9] Although the Nelson is much larger, the Hayes was a better route into the interior. Therefore, most of the Hudson's Bay Company's trade was done from York Factory on the Hayes, which was built in 1684.[10] In 1694-95 Father Marest recorded "The Assiniboine are thirty-five or forty days journey from the fort [Port Nelson]."[11]

"For more than two hundred years, from two to five sailing vessels, on an average, frequently with war ships conveying them, have sailed annually from Europe and America to Port Nelson, or other ports in Hudson's Bay and returned with cargoes the same season via the only available route, Hudson's Straits."[2]

20th-century boom and decline

editIn the early 1900s, the Government of Canada felt that a major harbour on Hudson Bay was needed for shipping grain from central Canada. In 1912 Port Nelson was selected as the site over Churchill (at the mouth of the Churchill River) to become the terminus of the Hudson Bay Railway, the construction of which had already begun from The Pas in 1910.[1]

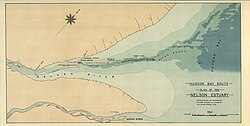

In the winter of 1912-13 the site was surveyed and construction of a wharf began in the spring, followed by buildings and other infrastructure built during the summer. The brand new Canadian research ship CSS Acadia was sent from Halifax to chart the harbour and approaches in the summer of 1913 and 1914. However the whole harbour project was fraught with problems from the start. Material shortages, labour disputes, storms, fires, and boating accidents led to major delays. Another setback was the necessity to completely redesign the harbour because the fast flowing Nelson River was building up silt on both sides of the wharf. Therefore, the harbour was changed to a small man-made island farther out in the river. The island was connected to the mainland with a seventeen-span truss bridge, built by Dominion Bridge Company of Montreal.[1] The Port Nelson, a wrecked dredge, currently lies on the island.[12]

When Canada entered the First World War, it resulted in further material and labour shortages, and more significantly, the loss of political and financial support. The project was able to continue a few more years until 1918 when all work stopped and the site was abandoned. The whole project was greatly criticized by several politicians, the media, which called it a "gigantic blunder", and even the project's chief engineer.[1]

The Hudson Bay Railway never reached Port Nelson and its tracks lay abandoned until 1927 when Churchill was chosen to become the northern shipping hub. Construction on the railway was restarted in 1927 and completed in 1929.[1]

In 1989 Parks Canada began the York Factory Oral History Project which included compiling stories by Swampy Cree Elders. Flora Beardy, a York Factory Cree woman conducted interviews with fourteen elders,[13] some of whom lived in Port Nelson.

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d e Malaher 1984.

- ^ a b John Macoun; George Monro Grant; Alexander Begg; John Campbell McLagan (1882). Manitoba and the great Northwest: the field for investment; the home of the emigrant, being a full and complete history of the country. World Publishing Company. pp. 595–687.

- ^ Fournier 2020.

- ^ a b c Nute 2016.

- ^ a b Johnson 1979.

- ^ Christianson 1980, p. 4.

- ^ Hutcheson 1982.

- ^ Ray 1998.

- ^ Vickers 1951–1952.

- ^

Robert Hood, C. Stuart Houston (1994). To the Arctic by Canoe, 1819-1821: The Journal and Paintings of Robert Hood, Midshipman with Franklin. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7735-1222-1. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

Port Nelson, at the mouth of the Nelson River, on the north shore of the peninsula and only twelve miles from York Factory, preceded York as an H.B.C. post in 1682-83. Sir Thomas Button named the river and harbour after Button's sailing master, who died and was buried there (Macoun et al 1882 page 595).

- ^ J. B. Tyrell, ed. (1931). Documents Relating to the Early History of Hudson Bay. Toronto: The Champlain Society. p. 124.

- ^ "Google Maps".

- ^ McNab 1999–2000.

Sources

edit- Christianson, David J. (1980). New Severn or Nieu Savanne: The Identification of an Early Hudson Bay Fur Trade Post (PDF) (Master's thesis). McMaster University.

- Fournier, Martin (2020) [1969]. "Radisson, Pierre-Esprit". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Hutcheson, Maud M. (1982) [1969]. "Gillam, Benjamin". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Johnson, Alice M. (1979) [1966]. "Bayly, Charles". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Malaher, David (Autumn 1984). "Port Nelson and the Hudson Bay Railway". Manitoba History (8). Manitoba Historical Society. ISSN 0226-5036.

- McNab, Miriam (1999–2000). "Review: Flora Beardy and Robert Coutts, Voices from James Bay: Cree Stories from York Factory". Oral History Forum. 19–20. Athabasca University Press: 137–139.

- Moriarty, G. Andrews (1979) [1966]. "Gillam, Zachariah". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Nute, Grace Lee (2016) [1966]. "Chouart de Groseilliers, Médard". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Ray, Arthur J. (1998). Indians in the Fur Trade. University of Toronto Press.

- Vickers, Chris (1951–1952). "The Assiniboines of Manitoba". Transactions of the Manitoba Historical Society. Series 3 (8). Manitoba Historical Society.

Further reading

edit- Beardy, Flora; Coutts, Robert (1996). Voices from Hudson Bay: Cree Stories from York Factory. Rupert's Land Record Society Series. McGill–Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773551435.

External links

edit57°03′17″N 92°35′54″W / 57.05472°N 92.59833°W