As with many countries, pollution in the United States is a concern for environmental organizations, government agencies, and individuals.

Billions of pounds of toxic chemicals are released into the air, land, and waterways in the U.S. each year. In 2019, approximately 21,000 facilities reported releasing 2.16 billion pounds of these chemicals onto land, 580 million pounds into the air, and 201 million pounds into water sources. Exposure to these pollutants can lead to various health problems, from short-term symptoms like headaches and temporary nervous system effects (e.g., "metal fume fever") to serious long-term risks such as cancer and early death.[1]

Pollution from U.S. manufacturing has declined massively since 1990 (despite an increase in production). A 2018 study in the American Economic Review found that environmental regulation is the primary driver of the reduction in pollution.[2]

Land

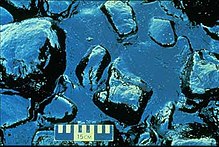

editLand can be polluted in two main ways: through the introduction of harmful chemical substances or through physical changes that make the land less useful or sustainable for future use. Waste management is always connected to land in some form, whether it involves calculating how much land is needed for a landfill to store a town's waste over the next 25 years, finding ways to protect important farmland from being taken out of production, or cleaning up abandoned waste sites that pose environmental risks. Waste managers are responsible for handling all these challenges, ensuring that land is used responsibly and that pollution is controlled.[3]

Examples of land pollution include:

Superfund

editAir

editAir pollution is caused predominantly by burning fossil fuels, cars, and much more.[4] Natural sources of air pollution include forest fires, volcanic eruptions, wind erosion, pollen dispersal, evaporation of organic compounds, and natural radioactivity. These natural sources of pollution often soon disperse and thin settling near their locale. However, major natural events such as volcanic activity can convey throughout the air spreading, thinning, and settling over continents.[5] Fossil fuel burning for heating, electrical generation, and in motor vehicles are responsible for about 90% of all air pollution in the United States.[6]

The issue of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change is inherently global in nature, transcending national borders and affecting countries worldwide, including the United States. The impact of greenhouse gas emissions is not solely determined by the actions of any single nation; rather, it is the result of cumulative emissions from multiple countries. While the U.S. contributes significantly to global emissions, the connection of the global economy means that efforts to mitigate climate change must involve international cooperation. The emissions of other countries, particularly rapidly industrializing nations, also influence the overall trajectory of climate change. Therefore, the United States faces the challenge of both reducing its own emissions and addressing the broader global dynamics that contribute to the problem, making it difficult to fully control the spread of climate-related issues on a national level.[7][8]

Water

editFreshwater

editIn a report published in the November 12, 2008 online issue of Environmental Science and Technology, researchers found that freshwater pollution by phosphorus and nitrogen costs U.S. government agencies, drinking water facilities and individual Americans at least $4.3 billion annually. Of that, they calculated that $44 million a year is spent just protecting aquatic species from nutrient pollution.[9] Currently, all through the United States, more than half of the rivers and lakes that span through the country don't meet standards required from environmental regulations. A large percentage of individuals living throughout America receive drinking water from such sources in which don't meet regulations for safe water to use.[10] Pollution from nitrogen and phosphorus in freshwater not only harms ecosystems but also costs Americans money, according to Kansas State University researchers. These pollutants, often from agricultural runoff, contribute to higher water treatment costs, increased bottled water expenses, and lower property values for lakeside homes. Additionally, recreational activities like fishing and boating can decline, hurting local economies. The researchers estimate that this pollution costs the U.S. at least $4.3 billion annually, with $44 million spent each year to protect aquatic species from nutrient pollution.[11]

Trace chemicals are common in both marine and freshwater ecosystems, but they are rarely found alone. Research on which chemicals often occur together and the best ways to identify these mixtures has been limited. In our study, we found that simple correlation analysis is more effective than principal component analysis (PCA) at identifying chemical mixtures. Unlike PCA, correlation analysis can handle unbalanced data and values below detection limits.[12]

Using this approach, we identified 10 common groups of chemicals that often appear together in U.S. freshwater systems. This method helps better understand how these chemical combinations affect aquatic environments. Our research shows that correlation analysis is a better tool for identifying co-occurring pollutants, based on data from 406 chemicals across 38 locations in the continental U.S.[12]

Furthermore, underwater pollution can lead to carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects to many individuals who are exposed to these pollutants[13]

Oceans

editOils

editPesticides

editReducing pesticide pollution is a global priority. In this study, we analyzed a dataset of 21.4 million geo-referenced grid cells to understand the factors driving differences in pesticide pollution risk across countries. We found that about one-third of these differences are due to variations in agricultural systems and policies, with key factors being pesticide regulations, the share of organic farming, and crop types. We also discovered a trade-off between pesticide pollution and soil erosion in the Americas and Asia, but not in other regions.[14] The use of DDT and its consequences as a pollutant is attributed as sparking the environmental movement in the United States.

Radioactivity

editWaste

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2009) |

Plastic Waste

editIn a 2015 study, the scientists also published a chart listing the top 20 nations contributing plastic waste, which has since been widely circulated. The top five plastic polluters included China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand. The United States ranked twentieth, the only wealthy nation on the list.[15] “We were not attempting to re-do the 2015 study,” says Kara Lavender Law, a marine scientist at the Sea Education Association in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and the new study’s lead author. “The whole point was to examine the United States.”[15] Analysing, 2016 data, the team found that as much as 3 percent of all plastic waste generated in the U.S. was either littered or illegally dumped in the environment. In all, the United States contributed up to 2.24 million metric tons into the environment in 2016, and of that, more than half—1.5 million metric tons—was along coastlines, meaning it had a high probability of slipping into the oceans.[15]

Plastic pollution is wreaking havoc on both the environment and human health. Microplastics, which come from the breakdown of plastic waste, are now found in 26% of marine fish—double the amount from just a decade ago. This environmental damage extends to wildlife, with species like turtles, fish, and seabirds suffering from ingesting plastic. The cost of these ecological impacts is estimated to be between $1.86 trillion and $268.5 billion by 2040.[16]

The financial burden of plastic waste management is also massive, with global costs for collecting, sorting, recycling, and disposing of plastics expected to range from $643 billion to $1.61 trillion by 2040. On top of this, plastics pose a growing human health crisis, with illnesses linked to plastic chemicals costing the U.S. between $384 billion and $403 billion annually. This combination of environmental and health-related costs highlights the urgent need to address the plastics crisis.[16]

Landfills

editIn the U.S., landfilling remains a common waste management method, with municipal, industrial, and hazardous waste landfills being the most prevalent, along with some emerging green waste landfills. While most landfills in the U.S. are regulated and engineered, illegal dumpsites still exist in certain areas. Landfilling can lead to several environmental and health issues, including contamination of groundwater from leachate, air pollution from airborne particles, odor pollution from municipal solid waste, and even marine pollution from runoff. This study explores these challenges within the U.S. context.[17]

Polystyrene

editWorldwide there are numerous environmental organizations attempting to ban the use of polystyrene. One such organization in the U.S. is Californians Against Waste.[18] The city of Berkeley, California, was one of the first cities in the world to ban polystyrene food packaging (called Styrofoam in the media announcements).[19][20] It was also banned in Portland, Oregon and Suffolk County, New York in 1990.[21] Now, over 20 US cities have banned polystyrene food packaging, including Oakland, California, on Jan 1, 2007.[20] San Francisco introduced a ban on the packaging on June 1, 2007:[22] Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin noted:

"This is a long time coming. Polystyrene foam products rely on nonrenewable sources for production, are nearly indestructible and leave a legacy of pollution on our urban and natural environments. If McDonald's could see the light and phase out polystyrene foam more than a decade ago, it's about time San Francisco got with the program."[23]

The overall benefits of the ban in Portland, Oregon have been questioned,[24] as have the general environmental concepts of the use of paper versus polystyrene.[25] The California and New York state legislatures are currently considering bills which would effectively ban expanded polystyrene in all takeout food packaging statewide.[26]

Lobbying

editPolicy

editThe United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an agency of the federal government of the United States charged with protecting human health and with safeguarding the natural environment: air, water, and land. The EPA was proposed by President Richard Nixon and began operation on 2 December 1970, when it was passed by Congress, and signed into law by President Nixon, and has since been chiefly responsible for the environmental policy of the United States.

State-level environmental policy, especially in clean air regulation, plays a key role in enforcement, air quality monitoring, and setting pollution standards that sometimes go beyond federal requirements set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, environmental programs at the state level vary widely. Some states implement stricter air quality standards, others have stronger enforcement mechanisms, and some are known for their technical expertise in policy.[27]

To understand these differences, analysts often develop frameworks to measure and explain variations in state environmental programs. These frameworks typically assess the overall "greenness" or effectiveness of a state's policy. However, these approaches can oversimplify the diverse goals of state programs by assuming that all states pursue a single, unified purpose.[27]

In reality, state environmental policy can be understood as having three distinct dimensions: (1) a focus on improving air quality, (2) the process of implementing and enforcing regulations, and (3) the collection and analysis of information necessary for policymaking. These dimensions are driven by different factors, and each state may prioritize them differently. Therefore, to better understand the differences in state-level environmental programs, it's important to consider each dimension separately.[27]

The Biden administration has finalized new tailpipe pollution standards that aim to slash carbon emissions from new passenger vehicles by over half by 2032. While the U.S. transition to fully electric vehicles might take longer than initially anticipated, these updated rules are still expected to reduce carbon pollution by 7.2 billion tons through 2055—just 1 percent less than the original proposal. In the end, this will be one of Biden's most impactful executive actions on climate change.[28]

The U.S. EPA has also announced nearly $330 million in Climate Pollution Reduction grants for Colorado as part of the Biden-Harris Administration's Investing in America agenda. The Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) will receive $199.7 million for a zero-emission building initiative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the Denver area, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050. The Colorado Energy Office (CEO) will receive $129 million to reduce methane emissions from landfills, coal mines, and other sources, and decarbonize commercial buildings. These projects aim to reduce air pollution, advance environmental justice, and support the clean energy transition in Colorado.[29]

Environmental discrimination

editEnvironmental justice is defined as "the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, sex, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies" by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.[30] It is a social movement that aims to ensure all citizens have equal rights and opportunities to reside in a safe environment. The movement began in the 1980s as evidence was mounting that companies were targeting minority and low-income communities. Due to the lack of community action among minorities and low-come, corporations found little resistance when applying to build environmentally polluting factories.[31]

Executive Order 12898

editOn February 11, 1994, President William Clinton signed Executive Order 12898 "Federal Actions To Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations". Its purpose was to create the "Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice". It provided directions to the "Working Group" on how to develop and manage an effective system for preventing environmental injustices. The "Working Group" was made up of various heads of federal agencies and tasked with creating guidelines for reporting, tracking, and developing regulations to curb environmental discrimination.[32]

Plan EJ 2014

editIn 2014, EPA has a strategy known as Plan EJ 2014. It is not, however, a rule or regulation.[33]

The goals of the plan are to: • Protect health in communities over-burdened by pollution • Empower communities to take action to improve their health and environment • Establish partnerships with local, state, tribal and federal organizations to achieve healthy and sustainable communities.

The Toxic 100

editCommon offenders of environmental discrimination are corporations that build environmentally hazardous sites. These are typically waste processing facilities, energy companies such as coal plants, chemical plants, and manufacturers who use specific chemicals known to be hazardous to both the environment and/or human health. Other industries known for being responsible for negatively impacting the United States include transportation and energy mining and drilling. A list called The Toxic 100 is maintained by the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), an institute at the university off Massachusetts Amherst, of the United States' top polluters. PERI uses a formula: Emissions (millions of pounds) x Toxicity x Population Exposure. Population is measured by its proximity to nearby residents, as well as, prevailing winds and the height of smokestacks. The data on chemical releases come from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Toxics Release Inventory (TRI).[34]

The Current Trend

editThe EPA and state agencies, like California's, collect air quality data on the main pollutants regulated by the Clean Air Act, called "criteria" pollutants. These monitors help ensure air quality standards are met and also provide important data for studying pollution trends. The information shows significant improvements in air quality over recent decades. From 1980 to 2019, levels of carbon monoxide, lead, and sulfur dioxide dropped by over 80%, and particulate matter also decreased substantially. However, ground-level ozone levels only fell by about one-third.[35] Tracking emissions from specific activities or operations is more complicated than monitoring pollution levels in the air because emissions are influenced by factors like energy use, pollution control systems, equipment maintenance, weather, and management practices. Emissions can be estimated using engineering models or by directly sampling pollutants from things like smokestacks. Despite this complexity, data shows that emissions from sectors such as industry and transportation have decreased in line with overall reductions in air pollution. For example, between 1980 and 2019, carbon monoxide emissions fell by 75%, and sulfur dioxide emissions dropped by 92%.[35]

Levels of air and water pollutants that are measured and controlled have dropped substantially in recent decades, far more than CO2 emissions. However, this improvement should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. For one, while U.S. industries create thousands of chemicals, the Safe Drinking Water Act only covers around 95 of them. Furthermore, since most pollutants are regulated because they are actively monitored, pollutants that are not regulated may not have seen the same level of reduction.[36]

The bigger deduction in air pollution compared to CO2 emissions raises questions about how the two are related. Some studies suggest that reducing CO2 emissions can also lower air pollution, like when we switch from coal to natural gas or renewable energy, which reduces both. But this isn't always the case. For example, pollution control devices like filters or exhaust cleaners may not reduce CO2 emissions and could even raise them because they need extra energy to operate. However, policies that reduce pollution might cut fossil fuel use, helping to lower both air pollution and CO2 emissions.[36]

The decrease in air pollution without a significant drop in CO2 seems to support the idea that policies aimed at reducing local pollutants don’t necessarily reduce CO2 emissions. This aligns with other studies showing that U.S. air pollution policies haven’t significantly impacted greenhouse gas emissions.[37]

See also

edit- Cancer Alley

- Environment of the United States

- Environmental racism

- Environmental racism in Europe

- Uranium mining and the Navajo people

- List of Superfund sites

- Toxic 100 - the top 100 polluters in the US

- Regional Clean Air Incentives Market (RECLAIM, an emission trading scheme in California)

- Anderson v. Cryovac - a landmark federal case concerning toxic contamination in Woburn, Massachusetts

- Hexavalent chromium pollution in the United States

References

edit- ^ Toman, Elisa L. (2023-10-01). "Something in the air: Toxic pollution in and around U.S. prisons". Punishment & Society. 25 (4): 867–887. doi:10.1177/14624745221114826. ISSN 1462-4745.

- ^ Walker, Reed; Shapiro, Joseph S. (2018). "Why Is Pollution from US Manufacturing Declining? The Roles of Environmental Regulation, Productivity, and Trade". American Economic Review. 108 (12): 3814–3854. doi:10.1257/aer.20151272. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Vallero, Daniel J.; Vallero, Daniel A. (2019-01-01), Letcher, Trevor M.; Vallero, Daniel A. (eds.), "Chapter 32 - Land Pollution", Waste (Second Edition), Academic Press, pp. 631–648, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815060-3.00032-3, ISBN 978-0-12-815060-3, retrieved 2024-12-13

- ^ Shapiro, Susan G. (2005). Environment And Global Community. IDEA. ISBN 978-1932716122.

- ^ Miller, G. Tyler Jr. Living in the Environment. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1987.

- ^ Bloom, Paul R. 'Environmental Encyclopedia. Acid Rain' . Detroit: Gale Research International Limited, 1994.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2015-12-23). "Overview of Greenhouse Gases". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2016-01-12). "Global Greenhouse Gas Overview". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-19.

- ^ Freshwater Pollution Costs at Least $4.3 Billion Annually Newswise, Retrieved on November 28, 2008.

- ^ Keiser, David A.; Shapiro, Joseph S. (2019-11-01). "US Water Pollution Regulation over the Past Half Century: Burning Waters to Crystal Springs?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 33 (4): 51–75. doi:10.1257/jep.33.4.51. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ^ Freshwater Pollution Costs at Least $4.3 Billion Annually Newswise, Retrieved on November 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Marshall, Melanie M.; McCluney, Kevin E. (2021-01-01). "Mixtures of co-occurring chemicals in freshwater systems across the continental US". Environmental Pollution. 268: 115793. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115793. ISSN 0269-7491.

- ^ Siddiqua, Ayesha; Hahladakis, John N.; Al-Attiya, Wadha Ahmed K. A. (2022-08-01). "An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 29 (39): 58514–58536. Bibcode:2022ESPR...2958514S. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-21578-z. ISSN 1614-7499. PMC 9399006. PMID 35778661.

- ^ Wuepper, David; Tang, Fiona H. M.; Finger, Robert (2023-01-01). "National leverage points to reduce global pesticide pollution". Global Environmental Change. 78: 102631. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102631. hdl:20.500.11850/589298. ISSN 0959-3780.

- ^ a b c "U.S. generates more plastic trash than any other nation, report finds". Environment. 2020-10-30. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved 2023-02-17.

- ^ a b Ignoring plastic pollution will cost us dearly (2024). (English ed.). ContentEngine LLC, a Florida limited liability company.

- ^ Siddiqua, Ayesha; Hahladakis, John N.; Al-Attiya, Wadha Ahmed K. A. (2022-08-01). "An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 29 (39): 58514–58536. Bibcode:2022ESPR...2958514S. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-21578-z. ISSN 1614-7499. PMC 9399006. PMID 35778661.

- ^ "Business Gives Styrofoam a Rare Redemption". Stockton Record. 21 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ Young, Paul. "www.berkeleydaily.org » Admission Requirements At The University Of Berkeley | Berkeley Daily".

- ^ a b Zamora, Jim Herron; Writer, Chronicle Staff (June 28, 2006). "Styrofoam food packaging banned in Oakland". SFGate.

- ^ "Californians Against Waste website". Archived from the original on June 8, 2009.

- ^ Goodyear, Charlie (November 7, 2006). "San Francisco / Committee approves ban on Styrofoam". SFGate.

- ^ Goodyear, Charlie; Writer, Chronicle Staff (June 27, 2006). "SAN FRANCISCO / Styrofoam ban for restaurants proposed for '07 / Business owners split on forced switch to eco-friendly options". SFGate.

- ^ Eckhardt, Angela (November 1998). "Paper Waste: Why Portland's Ban on Polystyrene Foam Products Has Been a Costly Failure" (PDF). Cascade Policy Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-03. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ^ Thomas, Robert A. (March 8, 2005). "Where Might We Look for Environmental Heroes?". Center for Environmental Communications, Loyola University, New Orleans. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ^ "AB 904". Archived from the original on May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c Potoski, Matthew; Woods, Neal D. (2002). "Dimensions of State Environmental Policies". Policy Studies Journal. 30 (2): 208–226. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2002.tb02142.x. ISSN 1541-0072.

- ^ Lavelle, By Marianne (2024-03-20). "Vehicle Carbon Pollution Would Be Cut, But More Slowly, Under New Biden Rule". Inside Climate News. Retrieved 2024-12-13.

- ^ United states : BidenHarris administration announces 3287M for community driven solutions to cut climate pollution across Colorado (2024). . Disco Digital Media, Inc.

- ^ "Environmental Justice | US EPA". Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ^ Pastor, Manuel (2001). Racial/Ethnic Inequality in Environmental-Hazard Exposure in Metropolitan Los Angeles. Berkeley, California: California Policy Research Center. p. 15.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "PERI: Toxic 100 Air Polluters 2013". Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Joseph S. (2022-01-01). "Pollution Trends and US Environmental Policy: Lessons from the Past Half Century". Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. 16 (1): 42–61. doi:10.1086/718054. ISSN 1750-6816.

- ^ a b Shapiro, J. S. (2021). Pollution trends and US environmental policy: Lessons from the last half century. (). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w29478

- ^ Shapiro, Joseph S (November 2021). "Pollution Trends and US Environmental Policy: Lessons from the Last Half Century". National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). NBER Working Paper No. w29478. Cambridge, Massachusetts. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3963706. OCLC 9332938017.

External links

edit- United States Environmental Protection Agency - Pollution page

- Scorecard Home (data about pollution in the United States)