This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

Bāyazīd Khān Ansārī (Pashto: بایزید خان انصاري; c. 1525 – 1585), commonly known as Pīr Rōshān or Pīr Rōkhān, was an Ormur warrior, Sufi poet and revolutionary leader.[3] He wrote mostly in Pashto, but also in Persian, Urdu and Arabic. His mother tongue was Ormuri. He is known for founding the Roshani movement, which gained many followers in present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, and produced numerous Pashto poets and writers.

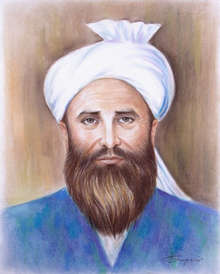

Pir Roshan | |

|---|---|

| پیر روښان | |

| |

| Born | Bāyazīd Khān Ansārī c. 1525 |

| Died | c. 1585[1] (aged 60) |

| Resting place | North Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan |

| Known for | Pashto poetry Roshani movement Pashto alphabet Pashtun nationalism |

| Notable work | Khayr al-Bayān |

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

| Father | Sheikh Abdullah[2] |

Pir Roshan created a Pashto alphabet, derived from the Arabic script with 13 new letters. A modified version of this alphabet continues to be used to write Pashto. Pir Roshan wrote Khayr al-Bayān, one of the earliest known books containing Pashto prose.

Pir Roshan assembled Pashtun tribesmen to fight against the Mughal emperor Akbar in response to Akbar's continuous military agitations. The Mughals referred to Pir Roshan as Pīr-e Tārīk (English: Dark Sufi Master).[not verified in body]

Due to Pir Roshan's spiritual and religious hold over a large portion of Pashtuns, Akbar enlisted religious figures into the struggle, most notably Pir Baba (Sayyid Ali Tirmizi) and Akhund Darweza.[not verified in body] The Mughals persecuted Pir Roshan's followers and executed many of them. A Mughal army eventually killed Pir Roshan and most of his sons. Only his youngest son, Pir Jalala, survived the attack, and later took up arms against the Mughals and became the new leader of the Roshani movement.[4]

Roshani followers in Waziristan, Kurram, Tirah, Loya Paktia, Loy Kandahar (including Kasi tribesmen), and Nangarhar continued their struggle against the Mughals for about a hundred years after Pir Roshan's death.

Biography

editBayazid was born in 1525 just outside Jalandhar in Punjab (present-day India), but early in his childhood, he moved with his family to their ancestral homeland of Kaniguram in South Waziristan (present-day Pakistan).[5] His grandfather was from the Lohgar Valley near Kabul in the country of the Barkis, but had immigrated to Waziristan, while his grandson was born in India.[6] His family was one of the many families who fled back to their ancestral land after the Turkic ruler Babur overthrew the Afghan Lodi dynasty in India in 1526.[7] His father, Abdullah, was an Islamic Qadi (judge). However, his father and relatives, and later Bayazid himself, also traded between Afghanistan and India. Bayazid was against many of the customs which prevailed in the area and the benefits which his family received due to being perceived as scholarly and devout. He was known for being stubborn, strong-willed and outspoken.

Bayazid began teaching at the age of 40. His message was well received by the Mohmand and Shinwari tribesmen. He then went to the Peshawar valley and spread his message to the Khalil and Muhammadzai. He sent missionaries (khalifas) to various parts of South and Central Asia. He sent one of his disciples, Dawlat Khan, along with his book Sirat at-Tawhid to Mughal Emperor Akbar. Khalifa Yusuf was sent along with his book Fakhr at-Talibin to the ruler of Badakhshan, Mirza Sulayman. Mawdud Tareen was sent to propagate his message to Kandahar, Balochistan, and Sindh. Arzani Khweshki was sent to India to convey the message to common people there. Besides, he also sent his deputies to Kabul, Balkh, Bukhara, and Samarkand.[8]

However, when he and his followers started spreading their movement amongst the Yousafzais, Bayazid came into direct confrontation with the orthodox followers of Pir Baba in Buner. He established a base in the Tirah valley where he rallied other tribes. In Oxford History of India, Vincent Smith describes this as the first "Pashtun renaissance" against Mughal rule.[9] When Mughal Emperor Akbar proclaimed Din-i Ilahi, Bayazid raised the flag of open rebellion. He led his army in several successful skirmishes and battles against Mughal forces, but they were routed in a major battle in Nangarhar by Mughal General Muhsin Khan.

During the 1580s, Yusufzais rebelled against the Mughals and joined the Roshani movement of Pir Roshan.[10] In late 1585, Mughal Emperor Akbar sent military forces under Zain Khan Koka and Birbal to crush the Roshani rebellion. In February 1586, about 8,000 Mughal soldiers, including Birbal, were killed near the Karakar Pass between Buner and Swat while fighting against the Yusufzai lashkar led by Kalu Khan. This was the greatest disaster faced by the Mughal army during Akbar's reign.[11] However, during the attack, Pir Roshan was himself killed by the Mughal army near Topi. In 1587, Mughal general Man Singh I defeated 20,000 strong Roshani soldiers and 5,000 horsemen. Pir Roshan's five sons, however, continued fighting against the Mughals until about 1640.[1]

Successors

editBayazid's sons were put to death with the exception of his youngest, Jalala, who was pardoned by Akbar as he was only 14 years old when he was captured. He later took up arms as Pir Jalala Khan and successfully engaged the Mughal armies. It is believed by some[who?] that the city of Jalalabad is named for him.[citation needed] After his death in battle, Jalala's nephew Ahdad Khan (also spelled Ihdad) took charge of the struggle.

As part of a concerted campaign to destroy the Roshanis around 1619 or 1620, Mahabat Khan, under the Emperor Jahangir, massacred 300 Daulatzai Orakzai in the Tirah. Ghairat Khan was sent to the Tirah region to engage the Roshani forces with a large military force via Kohat.[12] The Mughal forces were repulsed, but six years later Muzaffar Khan marched against Ahdad Khan. After several months of intense fighting, Ahdad Khan was killed. The death of Jahangir in 1627 led to a general uprising of the Pashtuns against Mughal forces.[12] Ahdad's son Abdul Qadir returned to Tirah to seek vengeance. Under his command, the Roshani defeated Muzaffar Khan's forces en route from Peshawar to Kabul, killing Muzaffar. Abdul Qadir plundered Peshawar and invested the citadel.[12]

It was not until the time of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (1628–1658) that a truce was brokered – between Akbar's grandson and Bayazid's great grandson. Bayazid Khan's descendants moved to Jullundhar and purchased lands to establish Basti Danishmandan, Basti Sheikh Derveish and later Basti Baba Khel.[citation needed] The Baba Khel branch of the Baraki lived in fortress-like compounds fighting the Sikhs who surrounded their lands until the early 20th century.

Legacy and assessment

editBayazid became known for his philosophical thinking with its strong Sufi influences, radical for the times and unusual for the region.[citation needed] The religious view of Pir Roshan was considered heretical by his contemporaries of Pashtun tribes from Khattak and Yusufzai.[13]

During the 19th century, orientalist scholars translating texts from Pashto and other regional texts termed his movement a "sect" which believed in the transmigration of souls and in the representation of God through individuals.[citation needed] Ideologically, history assessors with Left-wing progressivism view has regarded him as reformer who fight against conservative value among Pashtuns during his era.[13]

Conspiracy theorists have likened it to remnants of the Order of Assassins or having influenced the creation of the Illuminati in Bavaria.[citation needed] Many European researchers continue to hold this view, though others believe Mughal historians proliferated this as propaganda to dilute the major focus of the movement of fighting against Akbar and his Din-i-Ilahi.[citation needed]

The invading armies in Afghanistan seem to have paid significant attention from a historical perspective. During the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, Saint Petersburg State University Institute of Oriental Studies seemed to have been the institution tasked to study the Roshani movement in order to understand their foe.[citation needed]

Aminullah Khan Gandapur, in his book Tārīkh-i-Sarzamīn-i-Gōmal (History of the Gomal Land; National Book Foundation-2008,2nd Ed. ISBN 978-969-23423-2-2; P-57-63), ascribed a chapter to the Roshani movement and to their strife and achievement with the sword and the pen.

Following the 2002 invasion, Western scholars were again sent into the field to study and understand the movement. Sergei Andreyev,[14] was sent on UN assignment to Afghanistan, while simultaneously funded by the Institute of Ismaili Studies to research and write a book on the movement. There have been multiple editions of this book; however its sale and distribution remains restricted[clarification needed] in 2011.[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Schimmel, Annemarie (1980). Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. BRILL. p. 87. ISBN 9004061177.

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936, Volume 9. Houtsma, M Th. BRILL. 1987. p. 686. ISBN 9004082654. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Jonathan L. Lee (2022). Afghanistan:A History from 1260 to the Present. p. 58.

Pir Roshan, was from the small Ormur or Baraki tribe, whose mother tongue was Ormuri

- ^ Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. Infobase Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-0816061846.

- ^ Kakar, Hasan Kawun (27 August 2014). Government and Society in Afghanistan: The Reign of Amir 'Abd al-Rahman Khan. Univ of TX + ORM. ISBN 978-0-292-76777-5.

- ^ G.P Tate (2001). The Kingdom of Afghanistan: A Historical Sketch. Asian Educational Services. p. 201. ISBN 9788120615861.

- ^ Angelo Andrea Di Castro; David Templeman (2015). Asian Horizons: Giuseppe Tucci's Buddhist, Indian, Himalayan and Central Asian Studies. Monash University Publishing. pp. 544–584. ISBN 978-1922235336.

- ^ Mahmoud Masaeli; Rico Sneller (2020). Responses of Mysticism to Religious Terrorism: Sufism and Beyond. Gompel&Svacina. p. 91. ISBN 978-9463711906.

- ^ Vincent Smith; Oxford History of India volume Vol: VI; P- 325-40

- ^ "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 19– Imperial Gazetteer of India". Digital South Asia Library. p. 152. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780521566032.

- ^ a b c Tīrāh – Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 23, p. 389.

- ^ a b Ali Ahmad Jalali (2021). Afghanistan: A Military History from the Ancient Empires to the Great Game. University Press of Kansas. p. 252. ISBN 978-0700632633. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Dr. Sergei Andreyev".