The Pidjiguiti massacre (also spelled Pijiguiti[citation needed]) was an incident that took place on 3 August 1959 at the Port of Bissau's Pijiguiti docks in Bissau, Portuguese Guinea. Dock workers went on strike, seeking higher pay, but a manager called the PIDE, the Portuguese state police, who fired into the crowd, killing at least 25 people. The government blamed the revolutionary group African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), arresting several of its members. The incident caused PAIGC to abandon their campaign of nonviolent resistance, leading to the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence in 1963.

| Pidjiguiti massacre | |

|---|---|

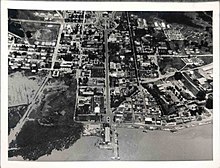

Aerial photo of Bissau, 1955; Pidjiguiti docks are front and centre | |

| Location | Port of Bissau, Bissau, Portuguese Guinea (present-day Bissau, Guinea-Bissau) |

| Coordinates | 11°51′00″N 15°35′00″W / 11.85000°N 15.58333°W |

| Date | 3 August 1959 |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | 25–50+ |

| Perpetrators | PIDE |

Background

editIn the 1950s, the Portuguese conglomerate Companhia União Fabril controlled much of the commerce on the Pijiguiti docks through a subsidiary called Casa Gouveia. Although the Portuguese colonial government had enacted a number of reforms in these years to try and quell the growing anti-colonial and pro-independence sentiments in the region, low wages and poor working conditions still served as catalysts for social unrest.[1]

The first major dock-workers' strike by employees of Casa Gouveia occurred on 6 March 1956. On this occasion, the Portuguese security forces and PIDE (political police) were ordered not to use force against the striking workers, presumably to avoid escalating the conflict. The workers, realizing this development, attempted to take the docks by force, and police reinforcements were required. Arrests were eventually made, but the episode left the police humiliated.[2]

The 1956 strike was overall unsuccessful, and wages remained extremely low. The continued growing unrest among the port workers was evident even to high-ranking colonial officials, including Army Under-Secretary of State Francisco da Costa Gomes who remarked in late 1958 that a dock-workers' revolt was likely and advised the governor to grant the wage demands of the workers in the interest of stability. This advice, however, was never acted upon.[3]

Preparations for another strike were organized in late July 1959, with workers meeting under the quay palm trees to discuss the specifics. Indeed, Amílcar Cabral sometimes referred to the incident as "the massacre of Pijiguiti Quay".[1][4][unreliable source?]

Massacre

editOn the morning of 3 August, the dock-workers were set to meet with Antonio Carreira, the manager of Casa Gouveia, to negotiate their wage increase. They had decided beforehand to stop working altogether at 3 o'clock in the afternoon should their demands not be met. The meeting did not prove fruitful, and the workers ceased their labour as planned. Carreira summoned the PIDE who arrived around 4 o'clock and demanded the workers resume their work. The strikers refused, and proceeded to barricade themselves in by closing the gates to the quay. Brandishing oars and harpoons, the strikers armed themselves in an attempt to deter the police from rushing in.[1]

The police, rather than risk defeat in open combat, opened fire on the striking workers, even throwing grenades. The workers had nowhere to run, and a number were killed within about 5 minutes. A few managed to escape via the water in their own boats, but the majority of them were pursued and arrested, or shot dead in the water. Between 25–50 workers died at the scene, along with many more wounded.[1]

News of the massacre spread quickly, and members of the revolutionary group PAIGC arrived on the scene quickly. The PAIGC were aware of the strike plans, and had endorsed the maneuver as an act of civil resistance against the colonial government. The PIDE quickly arrested PAIGC members, including Carlos Correia. The PAIGC's involvement gave the colonial authorities a convenient scapegoat on which to lay the blame for the unrest.[5]

Aftermath

editThe authorities blamed the PAIGC of fomenting discontent among the workers, and the party's supporters had to rethink long range strategies for achieving their goals. In September 1959 Cabral and several PAIGC members met in Bissau and decided nonviolent protest in the city would not bring about change. They concluded that the only hope for achieving independence was through armed struggle.[4][unreliable source?] This was the initial point in a 11-year armed struggle (1963–1974) in Portuguese Guinea that pitted 10,000 Soviet bloc-supported PAIGC soldiers against 35,000 Portuguese and African troops, and would eventually lead to independence in Cape Verde and all of Portuguese Africa after the Carnation Revolution coup of 1974 in Lisbon.[6][self-published source]

Commemoration

editThe day of the massacre, 3 August, is a public day of remembrance in Guinea-Bissau.[7]

Near the docks, there is now a large black fist known as the Hand of Timba which was erected as a memorial to those killed.[8]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Duarte Silva, António E. (2006). "Guinea-Bissau: The Cause of Nationalism and the Foundation of PAIGC". African Studies (in Portuguese). 9/10: 142–167. doi:10.4000/cea.1236 – via OpenEdition.

- ^ Rema, Henrique Pinto (1982). História das Missoes Católicas da Guiné (in Portuguese). Braga: Ed. Franciscana. p. 855.

- ^ Jaime, Drumond (1999). Angola: Depoimentos para a História Recente. Lisbon: Edições D. Jaime/H. Baber. pp. 285–286. ISBN 9789729827501.

- ^ a b Cabral, Amílcar (1961). "Guinea and Cabo Verde against Portuguese Colonialism". marxists.org. Retrieved 30 September 2019.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Carlos Correia: a testemunha do "Massacre de Pidjiguiti" | DW | 16 August 2014". dw.com. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Crónica da Libertação[self-published source]

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau Colonization Martyrs' Day". Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ "Crumbling architecture of former narco-state in Bissau". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

External links

edit- Luís Cabral: Crónica da Libertação (Lisboa: O Jornal. 1984. 65–73) – excerpts, commented by A. Marques Lopes

- Mário Dias: Pidjiguiti: comentando a versão do Luís Cabral — commentaries and historical corrections to Luís Cabral's "Crónica da Libertação"

- Efemérides — Pidjiguiti, violenta repressão em Bissau — extracts of a text by Josep Sanchez Cervelló, in "Guerra Colonial" — Aniceto Afonso, Matos Gomes

- Mário Dias: Os acontecimentos de Pindjiguit em 1959 (republished, with commentaries by Luís Graça). 21 February 2006

- Guerra na Guiné – Os Leões Negros: 1959 – Pidjiguiti

- Leopoldo Amado: Simbologia de Pindjiguiti na óptica libertária da Guiné-Bissau (Part I, Part II, Part III) February 2005