Peter (I) from the kindred Csák (Hungarian: Csák nembeli (I.) Péter; c. 1240 – 1283 or 1284) was a powerful Hungarian baron, landowner and military leader, who held several secular positions during the reign of kings Stephen V and Ladislaus IV. His son and heir was the oligarch Matthew III Csák, who, based on his father and uncles' acquisitions, became the de facto ruler of his domain independently of the king and usurped royal prerogatives on his territories.

Peter (I) Csák | |

|---|---|

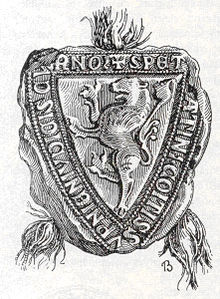

Seal of Palatine Peter Csák | |

| Palatine of Hungary | |

| Reign | 1275–1276 1277 1278 1281 |

| Predecessor | Nicholas Kőszegi (1st term) Nicholas Kőszegi (2nd term) Denis Péc (3rd term) Finta Aba (4th term) |

| Successor | Nicholas Kőszegi (1st term) Denis Péc (2nd term) Matthew II Csák (3rd term) Ivan Kőszegi (4th term) |

| Native name | Csák (I) Péter |

| Born | c. 1240 |

| Died | 1283 or 1284 |

| Noble family | gens Csák |

| Spouse(s) | unknown |

| Issue | Matthew III Csák |

| Father | Matthew I |

| Mother | Margaret N |

Family

editHe was born into the gens Csák as the youngest son of Matthew I, founder and first member of the Trencsén branch, who served as Master of the treasury (1242–1245), and Margaret from an unidentified noble family.[1] Peter's elder brothers were Mark I, ispán (comes) of Hont County in 1247, but there is no further information about him; Stephen I, Master of the stewards from 1275 to 1276 and from 1276 to 1279; and Matthew II, a notable general and Palatine of Hungary (1278–1280; 1282–1283).[2] He had also a younger sister, who married to the Moravian noble Zdislav Sternberg, a loyal bannerman of the Csák clan.[3] Their son, Stephen Sternberg (or "the Bohemian") later inherited the Csák dominion because of the absence of a direct adult male descendant after the death of Matthew III in 1321.[4]

Peter I married to an unknown noblewoman from an unidentified genus.[1] The marriage produced two children; the eldest one was Matthew III, who inherited his father and uncles' property and large-scale possessions,[5] which laid the foundation of a de facto independent domain, encompassing the north-western counties of the kingdom (today roughly the western half of present-day Slovakia and parts of Northern Hungary).[6] The second son was Csák, who served as bearer of the sword and died around 1300 without heir, leaving the clan heritage solely to his brother's branch.[7]

Biography

editLoyal to Duke Stephen

editAccording to a royal charter issued by Ladislaus IV on 23 May 1273, Peter played an active role in the 1260s civil war between King Béla IV of Hungary and his son, Stephen, who had taken over Transylvania with the title of duke.[1] The Csák clan supported Stephen in that emerging conflict, as a result Béla IV accused Peter of disloyalty and treason, thus he had to flee to the eastern parts of the kingdom, which ruled de facto independently by Stephen. Peter took refuge in Schwarzburg, the castle of Feketehalom (today: Codlea, Romania). After that he successfully fought against the Cumans, who allied Béla, near the Fortress of Déva (today: Deva, Romania), where he lost a lot of soldiers, but prevented the destruction of the region. Duke Stephen entrusted his faithful confidant Peter Csák with gathering a small contingent and marching into Northeast Hungary to rescue his family. Peter Csák successfully recaptured the fort of Baranka (today: Bronjka, Ukraine) from Duchess Anna's troops, but his small army was unable to achieve further victories and could not prevent the permanent internment of Queen Elizabeth and the children in Béla's domain.[8] Béla IV launched a campaign against the Sárospatak Castle, where Stephen's wife and children, among them was the infant Ladislaus, resided, however Peter I and his brother, Matthew II captured and imprisoned the king's spies and have pushed Béla to back off. As a result, the Transylvanian Saxons returned to their allegiance to Duke Stephen.[9] When Stephen and his small number of garrison was surrounded by Béla's royal army at the fort of Feketehalom in January 1265, Peter and Matthew Csák led the arriving rescue army. In January 1265, they returned from Upper Hungary to Transylvania, where they collected and reorganised the younger king's army and persuaded the Saxons to return to Stephen's allegiance. The battle took place along the wall of Feketehalom between the two armies at the end of January, while Duke Stephen led his remaining garrison out of the fort. The royalist troops were defeated soundly.[10]

In February 1265, Ernye Ákos led a royal campaign against Duke Stephen. However, he suffered a serious defeat and was himself captured by the enemy, the Csák army. Peter critically injured in the battle. According to a royal charter, Peter Csák, who was badly wounded, defeated Ernye during a duel.[11] Regardless of his injuries, Peter also participated in the Battle of Isaszeg in March 1265, where Stephen won a strategic victory over Béla's troops. Béla of Macsó fled from the battlefield, while Henry I Kőszegi and his sons were captured. After the defeat at Isaszeg, the king was forced to accept the authority of Stephen in the eastern parts of the kingdom.[12] On 23 March 1266, father and son confirmed the peace in the Convent of the Blessed Virgin on 'Rabbits' Island and Béla's partisans were released from captivity.[13] In the summer of 1266, Stephen invaded Bulgaria, seized Vidin, Pleven and other forts and routed the Bulgarians in five battles. Peter also took part in this campaign and fought like a "brave lion", according to a 1273 diploma.[14]

Peter I and his genus remained loyal to Stephen steadfastly, this fact proves that Peter's name is not listed in royal charters before 1270 and non-member of the Csák clan appeared in Stephen's account books, when the duke bribed his followers and his father's supporters. Peter and the Trencsén branch supported Stephen without compensation. They were waiting for the political ascent when the duke becomes king.[15]

Political career

editWhen Stephen V ascended the throne in 1270, Peter I was appointed Master of the stewards and head of Gacka (Gecske) źupa in the Kingdom of Croatia,[16] while his elder brother, Matthew II became Voivode of Transylvania.[17] Peter held these positions until the sudden death of Stephen V in August 1272, after that he was replaced by Reynold Básztély, as Master of the stewards.[18]

In 1271, Peter took part in a military campaign against Ottokar II of Bohemia, who violated the two-year truce, which had been concluded in 1270. He fought in the sieges of Pressburg and Moson. Alongside his brother Matthew Csák and Nicholas Baksa, Peter led an army to the river Moson to prevent the invading Czechs from crossing, but the troops of Ottokar II routed their army at Mosonmagyaróvár on 15 May 1271. Nevertheless, Stephen V won a decisive victory near the Rábca River. Peter's bravery and heroism during the battles had been documented by the royal charter of 1274. According to this, at the battle of Rábca, he saved the life of his former enemy, Béla, Duke of Macsó, who lost his horse in the battle.[15] Matthew and Peter were among those barons, who ratified the peace of Pressburg in July 1271.[19]

And at the Castle of Moson, he /Peter de genere Csák/ rescued Duke Béla (our dear cousin who had been fighting to the best of his ability) from the hands of our enemies who were endeavoring to kill him cruelly with all their might.

— King Ladislaus’s Charter of 1274 to Master Peter de genere Csák[20]

During the time when tensions emerged between Béla IV and his son, Stephen, two rival baronial groups developed, one of them was led by Henry I Kőszegi ("Henry the Great"), also involving the Gutkeled and Geregye clans, while the Trencsén branch of the Csák clan dominated the second group. Following the coronation of Stephen V in 1270, leaders of Béla IV's party fled to abroad from the potential retaliations, however they returned to Hungary, when the crown passed to the minor Ladislaus IV in August 1272. During the nominal regency of Queen Elizabeth the Cuman both sides wished to take part in the exercise of power. The rivalry between the two parties characterized the following years.[21] According to historian Bálint Hóman, twelve "changes of government" took place in the first five regnal years of Ladislaus IV.[22] Peter I regained his influence in June 1273, when he received land donations from the king, for instance Szenic in Nyitra County (today: Senica, Slovakia).[23] However Peter lost this estate in early 1274, when the Kőszegi baronial group enjoyed the confidence of Ladislaus IV again.[14]

The Csák brothers (Matthew II and Peter) and his allies successfully removed Joachim Gutkeled and Henry Kőszegi from power by the summer of 1274. However the two disgraced lords decided to capture and imprison Ladislaus and the Queen Mother in June 1274. Although Peter Csák liberated the king and his mother, Gutkeled and Kőszegi captured Ladislaus's younger brother, Andrew, and took him to Slavonia.[21] They demanded Slavonia in Duke Andrew's name, but Peter defeated their united forces in the Battle of Föveny at the end of September and liberated Andrew. Henry Kőszegi was killed in the battlefield, while Peter's face slashed. Following this Ladislaus IV and Peter launched a campaign against Ivan Kőszegi, Henry's son and plundered his province.[1] After that the Csák clan regained the lost positions; Matthew II was appointed Voivode of Transylvania, while Peter became ispán (comes) of Somogy and Sopron Counties, which dignities held until 1275.[24]

Despite the late Henry Kőszegi's betrayal, his family was able to retain its influence thus remained the main rival group of the Csák kindred. By mid-1275, the royal court expressed confidence towards the Kőszegi family, when Nicholas Kőszegi was elected Palatine, replacing Roland Rátót, Csák's ally. However another "change of government" happened before end of that year, when Peter was promoted to the position of Palatine. Matthew II Csák became Master of the treasury at the same time. Peter also held ispánate offices in Sopron, Nyitra and Somogy Counties, besiding the Palatine dignity.[25]

However, before June 1276, Peter lost all of these positions: he was replaced by Nicholas Kőszegi again and he was also accused of murder of a local noble in Somogy without reason.[26] He continued his struggle against the Kőszegis, when Peter's troops plundered and devastated the territory of the Diocese of Veszprém which headed by Bishop Peter Kőszegi, another son of Henry. During this attack all the treasures of the Veszprém cathedral chapter including the library of its school were burnt. The canonical university was never rebuilt after Peter's campaign.[21] Nevertheless, Peter regained the palatinal position after one year of forced political exile, beside that he also functioned as ispán of Somogy County.[25] In 1278, he served as Palatine for the third time, when he was succeeded by his brother Matthew II.[25] The Csák clan had four office-holder family members during that time and they had prominent role in creating of the alliance between Ladislaus IV and Rudolf of Habsburg against Ottokar II. In 1279, Peter became Master of the stewards and possibly held this dignity until his death in 1283 or 1284. He was also ispán of Pozsony and Moson Counties from 1279 to 1280.[18] Meanwhile, he served as Palatine for the fourth and final time in 1281.[27]

Possessions

editDue to his ownership in Szenic, he has been in close contact with the Bohemian noble Sternberg family from the other side of the Morava river. Peter established his domain on the left bank of the Danube. He guaranteed the liberties of burghers in Komárom (today: Komárno, Slovakia). It is possible that Peter had received the town around 1277 or 1278. He governed his estates from Komárom Fortress. He also purchased for 60 silver marks the land of Bosman in Southern-Nyitra from the Berencs kindred in 1281. Furthermore, Peter intended to gain lands and customs duties in Pozsony County, according to a charter following his death, he had taken away the letters of privilege of the nobles in Padány (today: Padáň, Slovakia) by force.[3]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Markó 2006, p. 220.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 31.

- ^ a b Kristó 1986, p. 50.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 199.

- ^ Fügedi 1986, p. 159.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 126.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 51.

- ^ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 42.

- ^ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Fügedi 1986, p. 150.

- ^ Markó 2006, p. 268.

- ^ a b Kristó 1986, p. 46.

- ^ a b Kristó 1986, p. 43.

- ^ Zsoldos 2011, p. 274.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 34.

- ^ a b Zsoldos 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Rudolf 2023, pp. 266, 276.

- ^ Kristó, Gyula. Középkori históriák oklevelekben (1002–1410).

- ^ a b c Engel 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Fügedi 1986, p. 153.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 45.

- ^ Zsoldos 2011, pp. 194, 199.

- ^ a b c Zsoldos 2011, p. 21.

- ^ Kristó 1986, p. 48.

- ^ Zsoldos 2011, p. 22.

Sources

edit- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- (in Hungarian) Fügedi, Erik (1986). Ispánok, bárók, kiskirályok ("Ispáns, Barons, Oligarchs"). Nemzet és emlékezet, Magvető Könyvkiadó. Budapest. ISBN 963-140-582-6

- (in Hungarian) Kristó, Gyula (1986). Csák Máté ("Matthew Csák"). Magyar História, Gondolat. Budapest. ISBN 963-281-736-2

- (in Hungarian) Markó, László (2006). A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig – Életrajzi Lexikon ("The High Officers of the Hungarian State from Saint Stephen to the Present Days – A Biographical Encyclopedia") (2nd edition); Helikon Kiadó Kft., Budapest; ISBN 963-547-085-1.

- Rudolf, Veronika (2023). Közép-Európa a hosszú 13. században [Central Europe in the Long 13th Century] (in Hungarian). Arpadiana XV., Research Centre for the Humanities. ISBN 978-963-416-406-7.

- (in Hungarian) Zsoldos, Attila (2007), Családi ügy - IV. Béla és István ifjabb király viszálya az 1260-as években ("A Family Affair - The Conflict of Béla IV and Junior King Stephen in the 1260s"), História - MTA Történettudományi Intézete, Budapest, ISBN 978-963-9627-15-4

- (in Hungarian) Zsoldos, Attila (2011). Magyarország világi archontológiája, 1000–1301 ("Secular Archontology of Hungary, 1000–1301"). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. Budapest. ISBN 978-963-9627-38-3