Paterson is an epic poem by American poet William Carlos Williams published, in five volumes, from 1946 to 1958. The origin of the poem was an eighty-five line long poem written in 1926, after Williams had read and been influenced by James Joyce's novel Ulysses. As he continued writing lyric poetry, Williams spent increasing amounts of time on Paterson, honing his approach to it both in terms of style and structure. While The Cantos of Ezra Pound and The Bridge by Hart Crane could be considered partial models, Williams was intent on a documentary method that differed from both these works, one that would mirror "the resemblance between the mind of modern man and the city."[1]

While Williams might or might not have said so himself, commentators such as Christoper Beach and Margaret Lloyd have called Paterson his response to T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land and Pound's Cantos. The long gestation time of Paterson before its first book was published was due in large part to Williams's honing of prosody outside of conventional meter and his development of an overall structure that would stand on a par with Eliot and Pound yet remain endemically American, free from past influences and older forms.

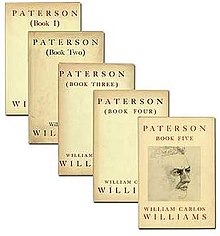

The poem is composed of five books and a fragment of a sixth book. The five books of Paterson were published separately in 1946, 1948, 1949, 1951 and 1958, and the entire work collected under one cover in 1963. A revised edition was released in 1992. This corrected a number of printing and other textual errors in the original, especially discrepancies between prose citations in their original sources and how they appeared in Williams's poem. Paterson is set in Paterson, New Jersey, whose long history allowed Williams to give depth to the America he wanted to write about, and the Paterson Falls, which powered the town's industry, became a central image and source of energy for the poem.[2]

Background

editInitial efforts

editIn 1926, influenced by his reading of the novel Ulysses by James Joyce, William Carlos Williams wrote an 85-line poem entitled "Paterson"; this poem subsequently won the Dial Award.[3] His intent in this poem was to do for Paterson, New Jersey what Joyce had done for Dublin, Ireland, in Ulysses.[4] Williams wrote, "All that I am doing (dated) will go into it."[5] In July 1933, he reattempted the theme in an 11-page prose poem, "Life Along the Passaic River."[6] By 1937, Williams felt he had enough material to start a large-scale poem on Paterson but realized that the project would take considerable time to complete.[7] Moreover, his then-busy medical practice precluded his attempting such a project at that time.[7] This did not stop Williams from taking some preliminary steps in the meanwhile. He wrote the poem "Paterson, Episode 17" in 1937 and would recycle it into the major work 10 years later.[8] "Morning," written in 1938, was another poem intended for Paterson.[9] In 1939, Williams sent James Laughlin at New Directions Publishing an 87-page sheaf of poems labeled "Detail and Parody for the Poem Paterson." This collection as such was not published.[10] However, 15 of its "details," titled "For the Poem Patterson [spelling Williams]" appeared in the collection The Broken Span, which New Directions released in 1941.[11]

Addressing The Waste Land

editOne reason Williams deliberated on Paterson was his longstanding concern about the poem The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot, which with its overall tone of disillusionment had tapped into a much larger sense of cultural ennui that had arisen in the aftermath of World War I and become a touchstone for the Lost Generation.[12] As Margaret Lloyd states in her critical reappraisal of Paterson, "many critics and poets indicate their poetical inclinations by aligning themselves specifically with T.S. Eliot or William Carlos Williams, and ... Paterson was, from its very conception, intended to be a 'detailed reply' (SL, 239) to the Eliot bias of modern poetry."[13]

To Williams, Eliot "had moved into a vacuum with his poem," in Mariani's words, and taken American poetry with it.[12] Moreover, Eliot's use of conventional meter (though varied in places by speech rhythms) did not seem endemic to American speech and thus seemed outside the course that American poetry had seemed headed since the poetry of Walt Whitman.[14] For American poetry (and by extension his own work) to progress, Williams argued, it needed to move away from foreign traditions and classic forms and essentially find its own way.[15]

Hart Crane, with whom Williams was in contact, had felt similarly about The Waste Land.[16] However, Williams dismissed Crane's reaction to The Waste Land, his long poem The Bridge, as "a direct step backward to the bad poetry of any age but especially to that triumphant regression [French symbolism] which followed Whitman and imitates...the Frenchman [Mallarmé] and came to a head in T.S. Eliot excellently."[17] Williams also studied The Cantos by Ezra Pound, the first 30 parts of which appeared in 1931. While Williams noted that Pound, in Mariani's words, "had managed to lift the language to new heights," he had also "deformed the natural order of speech at times...while somehow saving the excellences and even the forms of old."[18]

Developing form and method

editWilliams, according to Mariani, concluded that tackling Paterson meant "to find a way beyond Eliot's poetic, and beyond Pound's, as well...in sculpting the words themselves, words with hard, concrete, denotative jagged edges."[16] At the same time, the New Jersey dialect the poet wanted to set into verse could sound, as biographer Paul Mariani phrases it, "unrelievedly flat."[19] In a note that accompanied the "Detail and Parody" manuscript he sent to New Directions, Williams told Laughlin and his associate Jim Higgins, "They are not, in some ways, like anything I have written before but rather plainer, simpler, more crudely cut...I too have to escape from my own modes."[20] The formal solution eluded Williams into the early 1940s. In December 1943, he wrote Laughlin, "I write and destroy, write and destroy. [Paterson is] all shaped up on outline and intent, the body of the thinking is finished but the technique, the manner and the method are unresolvable to date."[21] Finding a form of American vernacular that would facilitate poetic expression, which approximated speech rhythms but avoided the regularity of their patterns as both Joyce and Walt Whitman had done, proved a long trial-and-error process.[22] This period proved doubly frustrating as Williams became impatient with his progress; he wanted to "really go to work on the ground and dig up a Paterson that would be a true Inferno."[23]

Williams also studied Pound's Cantos for clues on how to structure the large work he had in mind. Muriel Rukeyser's US1 also caught Williams' attention for its use, with a technical skill that seemed to rival Pound's in The Cantos, of such diverse and seemingly prosaic materials as notes from a congressional investigation, an X-ray report and a physician's testimony on cross-examination.[24] He wrote to fellow poet Louis Zukofsky, "I've begun to think about poetic form again. So much has to be thought out and written out there before we can have any solid criticism and consequently well-grounded work here."[20]

In 1944, Williams read a poem by Byron Vazakas in Partisan Review that would help lead him to solutions in form and tone for Paterson. Vazakas had written to Williams before the poem had appeared. Williams now wrote Vazakas, praising him for the piece and urging him to collect some of his work into a book. He also asked to see more of Vazakas's work as soon as possible. According to Mariani, the way Vazakas combined "a long prose line" and "a sharply defined, jagged-edged stanza" to stand independent of each other yet remain mutually complementary suggested a formal solution.[25] Williams also found an "extension, a loosening up" in tone in Vazakas's poems—an approach Williams would find seconded in the poem "America" by Russell Davenport in Life Magazine that November.[26] Between these works and Williams's own continued efforts, he hit upon what Mariani calls the "new conversational tone—authoritative, urbane, assured" that Williams sought for his large-scale work.[27] By late June 1944, Williams was working in earnest on the notes he had accumulated for Paterson, "gradually arranging and rearranging the stray bits with the more solid sections" as he approached a "first final draft" of what would become Paterson I.[28]

In his preface to the revised edition of Paterson, editor Christopher MacGowan points out that, even with Williams' protracted challenges in finalizing the poem's form, he "seems to have always felt close to the point of solving his formal problems."[29] He promised it to Laughlin for the Spring 1943 book list of New Directions.[29] He told Laughlin April 1944 that Paterson was "near finished" and nine months later that it was "nearing completion."[30] Even after he had received the galley proofs of Book I in September 1945, Williams was dissatisfied and revised the work extensively. This delayed its appearance in print to June 1946.[29]

Composition

editWilliams saw the poet as a type of reporter who relays the news of the world to the people. He prepared for the writing of Paterson in this way:

I started to make trips to the area. I walked around the streets; I went on Sundays in summer when the people were using the park, and I listened to their conversation as much as I could. I saw whatever they did, and made it part of the poem.[31]

The Poetry Foundation's biography on Williams notes the following source:

With roots in his [short] 1926 poem [also entitled] "Paterson," Williams took the city as "my 'case' to work up. It called for a poetry such as I did not know, it was my duty to discover or make such a context on the 'thought'."[32]

While writing the poem, Williams struggled to find ways to incorporate the real world facts obtained during his research in preparation for its writing. On a worksheet for the poem, he wrote, "Make it factual (as the Life is factual-almost casual-always sensual-usually visual: related to thought)". Williams considered, but ultimately rejected, putting footnotes into the work describing some facts. Still, the style of the poem allowed for many opportunities to incorporate 'factual information', including portions of his own correspondence with the American poet Marcia Nardi and fellow New Jersey poet Allen Ginsberg as well as historical letters and articles concerning figures from Paterson's past (like Sam Patch and Mrs. Cumming) that figure thematically into the poem.[33]

Response

editThe Poetry Foundation biography on Williams notes the following critical response to Williams' Modernist epic:

[Williams biographer James] Breslin reported "reception of the poem never exactly realized his hopes for it." Paterson's mosaic structure, its subject matter, and its alternating passages of poetry and prose helped fuel criticism about its difficulty and its looseness of organization. In the process of calling Paterson an "'Ars Poetica' for contemporary America," Dudley Fitts complained, "it is a pity that those who might benefit most from it will inevitably be put off by its obscurities and difficulties." Breslin, meanwhile, accounted for the poem's obliqueness by saying, "Paterson has a thickness of texture, a multi-dimensional quality that makes reading it a difficult but intense experience."[32]

Poet/critic Randall Jarrell praised Book I of the poem with the following assessment:

Paterson (Book I) seems to me the best thing William Carlos Williams has ever written. . .the organization of Paterson is musical to an almost unprecedented degree. . . how wonderful and unlikely that this extraordinary mixture of the most delicate lyricism of perception and feeling with the hardest and homeliest actuality should ever have come into being! There has never been a poem more American.[34]

However, Jarrell was greatly disappointed with Books II, III, and IV of the poem, writing the following:

Paterson has been getting rather steadily worse [with each subsequent Book]... All three later books are worse organized, more eccentric and idiosyncratic, more self-indulgent, than the first. And yet that is not the point, the real point: the poetry, the lyric rightness, the queer wit, the improbable and dazzling perfection of so much of Book I have disappeared—or at least, reappear only fitfully.[34]

Awards

editThe U.S. National Book Award was reestablished in 1950 with awards by the book industry to authors of 1949 books in three categories. William Carlos Williams won the first National Book Award for Poetry.[35]

References in popular culture

editWilliams himself "looms large" in Jim Jarmusch's 2016 film, Paterson starring Adam Driver.[36] According to a 2017 review, the "linguistic infrastructure" of the film was informed by concepts found in the five-volume poem.[36]

References

edit- ^ Beach, Christopher (2003). The Cambridge introduction to twentieth-century American poetry (1st publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge UP. pp. 109–16. ISBN 9780521891493.

- ^ MacGowan, Christopher (2003). William Carlos Williams: poetry for young people. New York: Sterling. p. 8. ISBN 9781402700064.

- ^ Mariani, pp. 204, 263.

- ^ Mariani, p. 263.

- ^ As quoted in Mariani, p. 263.

- ^ Mariani, pp. 343–4.

- ^ a b Mariani, pp. 387–8.

- ^ Mariani, p. 414.

- ^ Mariani, p. 415.

- ^ Mariani, pp. 417–18.

- ^ Mariani, p. 445.

- ^ a b Mariani, p. 191.

- ^ Lloyd, 23.

- ^ Layng, p. 187; Mariani, p. 191.

- ^ Holsapple, 84.

- ^ a b Mariani, p. 250.

- ^ As quoted in Mariani, p. 328, comments in brackets Mariani.

- ^ Mariani, pp. 311–12.

- ^ Mariani, p. 418.

- ^ a b As quoted in Mariani, p. 418.

- ^ As quoted in Mariani, p. 486.

- ^ Layne, p. 188; Mariani, pp. 418–19.

- ^ As quoted in Mariani, p. 419.

- ^ Mariani, p. 417.

- ^ Mariani, p. 492.

- ^ Mariani, pp. 499–500.

- ^ Mariani, p. 500.

- ^ As quoted in Mariani, pp. 492–3.

- ^ a b c MacGowan, p. xi.

- ^ As quoted in MacGowan, p. xi.

- ^ Bollard, Margaret Lloyd (1975). "The "Newspaper Landscape" of Williams' "Paterson"". Contemporary Literature. 16 (3). University of Wisconsin Press: 317–327. doi:10.2307/1207405. JSTOR 1207405.

- ^ a b Poetry Foundation biography on Williams

- ^ Bollard (1975), p. 320

- ^ a b Jarrell, Randall. "Paterson by William Carlos Williams." No Other Book: Selected Essays. New York: HarperCollins, 1999.

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1950". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ^ a b Crust, Kevin (18 January 2017). "Jim Jarmusch, Ron Padgett and the sublime poetry of 'Paterson'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

Sources

edit- Beach, Christopher, The Cambridge Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Poetry (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003). ISBN 0-521-89149-3.

- Holsapple, Bruce, "Williams on Form: Kora in Hell". In Hatlen, Burton and Demetres Tryphonopoulous (eds), William Carlos Williams and the Language of Poetry (Orono, Maine: The National Poetry Foundation, 2002). ISBN 0-943373-57-3.

- Layne, George W., "Rephrasing Whitman: Williams and the Visual Idiom." In Hatlen, Burton and Demetres Tryphonopoulous (eds), William Carlos Williams and the Language of Poetry (Orono, Maine: The National Poetry Foundation, 2002). ISBN 0-943373-57-3.

- Lloyd, Margaret, William Carlos Williams' Paterson: A Critical Reappraisal (London and Cranbury, New Jersey: Associated University Press, 1980). ISBN 0-8386-2152-X.

- Mariani, Paul, William Carlos Williams: A New World Naked (New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1981). ISBN 0-07-040362-7.

- Williams, William Carlos, ed. Christopher MacGowan, Paterson: Revised Edition (New York: New Directions, 1992). ISBN 0-8112-1225-4.