The Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii) is a species of hagfish. It lives in the mesopelagic to abyssal Pacific Ocean, near the ocean floor. It is a jawless fish and has a body plan that resembles early Paleozoic fishes. They can excrete copious amounts of slime in self-defense.

| Pacific hagfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Myxini |

| Order: | Myxiniformes |

| Family: | Myxinidae |

| Genus: | Eptatretus |

| Species: | E. stoutii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Eptatretus stoutii (Lockington, 1878)

| |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

| |

Description

editThe Pacific hagfish has a long, eel-like body, but is not closely related to eels. Maximum body lengths of 63 cm (25 in) have been reported;[4] typical length at maturity is around 42 cm (17 in). It is dark brown, gray or brownish red, often tinted with blue or purple. The belly is lighter and sometimes has larger white patches. It has no true fins, but there is a dorsal fin-fold. The head, as in all agnathans, does not have jaws, and the sucker-like mouth is always open,[5] with 8 barbels around it. There are no visible eyes.[4] Hagfish also only have one nostril, which is located above the mouth.[6]

Starting about one quarter of their body length from the front are 10–14 gill pores.[4]

Hagfish have loosely fitted, slimy skins, and are notorious for their slime-production capability. When disturbed, they ooze proteins from slime glands in the skin that respond to water by becoming a slimy outer coating, expanding into a huge mass of slime. This makes the fish very unsavory to predators, and can even be used to clog the gills of predatory fish. Pacific hagfish can create large amounts of slime in just minutes.[7] The slime is notoriously difficult to remove from fishing gear and equipment, and has led to Pacific fishermen bestowing the nickname of 'slime eel' on the species.[8]

Slime production in hagfish is also an energetically costly process, and regeneration has been shown to take a long time. The limiting factor in producing new slime is the replacement of threads of slime proteins. Studies have shown that the time to complete regeneration is roughly 24-28 days. Slime can still be ejected before this period is finished, but with less material than when performed with full glands.[9]

The eyes of the Pacific hagfish are very basic compared to other vertebrates. Research on Eptatretus stoutii eye tissues has shown that the eyes of hagfishes do not represent a basal form of the vertebrate eye. Instead, hagfish eyes are likely a regressed form of a more complex, basal vertebrate eye that was present in the common ancestor of modern vertebrates.[10] The Pacific hagfish also has a transparent window of skin stretched over the eye, which appear as white spots on the fish. The internal structures of the eye (retina and photoreceptors) are also more complex than previously thought. The increased eye complexity found in Eptatretus stoutii may relate to their ecology, as some species within this genus have been observed exhibiting predatory hunting behavior.[10]

Similar species

editEptatretus deani has its first gill pore closer to the head.[4] Lampetra tridentata has visible eyes and 7 gill pores. Myxine limosa has gill pouches with one exterior connection.[4]

Taxonomy

editThe genus Eptatretus means “seven perforations”, referring to the seven gill apertures of E. cirrhatus, another hagfish within the genus. The epithet stoutii is in honor of Arthur B. Stout, former surgeon and corresponding secretary of the California Academy of Sciences.[11] The Pacific hagfish confused scientists at first because Carl Linnaeus mistakenly classified the organism as an "intestinal worm".[11]

Distribution and habitat

editThe Pacific hagfish occurs in the Northeast Pacific Ocean from southeast Alaska to Baja California, Mexico.[4] It inhabits fine silt and clay bottoms on the continental shelves and upper slopes at depths from 16–966 metres (52–3,169 ft). The species appears to be abundant within its range.[1] The Pacific hagfish also was discovered off the coast of Costa Rica in 2015, which extends the southern part of their range by roughly 3500 kilometers than was previously thought. It is unclear whether this was a recent species expansion, or if this section of the population has not been sampled.[12]

Biology

editReproduction

editHagfish fertilize their eggs externally after the female has laid them. On average females lay about 28 eggs, about 5 mm (0.20 in) in diameter, which are carried around after they have been fertilized. Females will however try to stay in their burrows during this period to ensure the protection of their eggs.[13] Pacific hagfish also have a sex ratio of roughly 1:1. This species also exhibits slight sexual dimorphism, with females growing to slightly smaller sizes than males. E. stoutii is iteroparous, and spawns on an irregular time schedule. These cycles can take up to 2-3 years before new spawning .[14] Pacific hagfish juveniles also exhibit hermaphroditism, and do not become differentiated into separate sexes until after maturity.[14]

Diet and feeding

editWhile Pacific hagfish likely take polychaete worms and other invertebrates from the sea floor, they are also known to enter dead, dying or inhibited large fish through the mouth or the anus, and feed on their viscera.[4][5] The diet of other hagfish species includes shrimps, hermit crabs, cephalopods, brittle stars, bony fishes, sharks, birds and whale flesh,[12] but specific information about the Pacific hagfish diet is lacking. The Pacific hagfish's skin can absorb amino acids.[15] Additionally, hagfish do not actively drink water, as their internal salt concentration must match the surrounding seawater.[16]

The feeding apparatus of hagfish is unique among fishes and is primarily composed of soft tissues and a prominent dental plate. This contrasts with bony fish, which have multiple bones to provide rigidity in translating biting force. Despite this, hagfish are still capable of bite forces similar to jawed vertebrates.[17] The dental plate consists of two symmetrical halves that open and close laterally. This use of this plate in practice resembles a grasping and tearing motion and relies on muscles that run posteriorly from the head. Since hagfish do not have bones to attach their muscles to, the collective term for this feeding musculature is called a hydrostat.[18] In addition, juveniles do not have a larval stage and resemble smaller adults. This means that juveniles feed in the same way as adults, but are only capable of taking smaller amounts of food.[18]

Anoxic survival

editHagfish have an incredibly low metabolic rate which is regarded as the lowest among fishes.[19] This adaptation allows them to survive in areas of water with low to zero oxygen content. Tolerance to low oxygen conditions is useful to hagfish as it allows them to function inside of large fish or mammal carcasses where there are low dissolved oxygen levels. Additionally, hagfish may also experience low oxygen levels when burrowing into sediments on the sea floor.[19]

Movement

editHagfish can tie their bodies into knots, an adaptation becomes useful when the fish needs to remove the suffocating nature of its own slime by pulling itself through a knot. The knots also provide aid in the process of ripping apart meat.[20] Knotting is possible due to the lack of vertebrae, and presence of flexible, cartilaginous notochords. The outer layer of a hagfish’s skin acts as an ideal surface for creating knots with low friction. By having no paired fins along the body, as seen in more derived fishes, the body plan is free to create knots with no appendages obstructing the knot.[21] Hagfish can tie their bodies into overhand, figure eight, and several other higher order knots. Hagfish of the Eptatretus genus were found to also to employ knotting behaviors much more frequently than sea snakes and moray eels, which are also capable body knotting.[21] Compared to other species of hagfish, the Pacific hagfish has also been observed preferring a coiled position when resting. This is in opposition to other species such as Atlantic hagfish (M. glutinosa) and Gulf hagfish (Eptatretus springeri).[21]

Hagfish are also able to squeeze through small openings and crevices. In fact, the Pacific hagfish is able to fit through spaces that are less than one half of its total body width.[22] This is accomplished by a combination of factors, which include blood volume, a large subcutaneous sinus, and loose skin. Hagfish have roughly twice as much blood proportional to their body size when compared to mammals. Nearly one third of this blood is stored in what is called a subcutaneous sinus, which is a space in between the skin and muscle of the hagfish. This blood-filled compartment nearly surrounds the entire body of the hagfish, and is loose.[22] Since this sinus is loose and constantly filled with fluid, the hagfish can push the blood to other parts of its body, which is what allows it to fit through such small openings. It is believed this behavior is utilized to escape predation.[22] This behavior is useful as it allows hagfish to escape predation by hiding in small burrows or rock crevices.

The loose skin of E. stoutii also confers extra protection from puncture wounds. The skin itself is not puncture resistant, but allows internal organs and musculature to move out of the way from penetrating objects (Boggett 2017). This contrasts with fishes such as teleosts, which have tight skin attached to their body core allowing for more sustained damage from puncture wounds.[23]

The Pacific hagfish employs an anguilliform swimming mode, as it has an elongate, eel-like body plan. A study found that both E. stoutii, and Myxine glutinosa (Atlantic hagfish) utilize high amplitude, undulatory waves to swim. This means that hagfish pass a wave down the length of their body which propels them forward, beginning at their head. The reverse direction can also be obtained when the hagfish starts a wave at the opposite end of the body.[24]

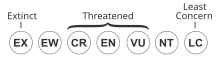

Conservation

editConservation status for this species is data deficient.[1] Demand for hagfish has increased despite the limited amount of stock assessment data, and more data on their reproductive ecology is needed to make informed management decisions. However, the low reproductive rate of hagfishes is concerning to the health of active fisheries.[14]

Use by humans

editThere is a well-developed hagfish fishery on the US West Coast that mostly supplies the Asian leather-market. Hagfish-skin clothing, belts, or other accessories are advertised and sold as "yuppie leather" or "eel-skin".[13][1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Mincarone, M.M. (2011). "Eptatretus stoutii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T196044A8997397. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T196044A8997397.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (2017). "Myxinidae". FishBase version (02/2017). Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Van Der Laan, Richard; Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ronald (11 November 2014). "Family-group names of Recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (1): 1–230. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3882.1.1. PMID 25543675.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gilbert, Carter R.; Williams, James D. (2002) [1983]. National Audubon Society Field Guide to Fishes (rev. ed.). Knopf. p. 34. ISBN 0-375-41224-7.

- ^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Eptatretus stoutii". FishBase. December 2015 version.

- ^ Døving, Kjell B. (1998), "The Olfactory System of Hagfishes", The Biology of Hagfishes, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 533–540, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-5834-3_33, ISBN 978-94-010-6465-1, retrieved 2024-11-07

- ^ Zintzen, V.; Roberts, C. D.; Anderson, M. J.; Stewart, A. L.; Struthers, C. D.; Harvey, E. S. (2011). "Hagfish predatory behaviour and slime defence mechanism". Scientific Reports. 1 (1): 131. Bibcode:2011NatSR...1..131Z. doi:10.1038/srep00131. PMC 3216612. PMID 22355648.

- ^ Theisen, Birgit (1976). "The olfactory system in the Pacific hagfishes Eptatretus stoutii, Eptatretus deani, and yxine circifrons". Acta Zoologica. 57 (3): 167–173. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.1976.tb00224.x.

- ^ Schorno, Sarah; Gillis, Todd E.; Fudge, Douglas S. (2018-01-01). "Cellular mechanisms of slime gland refilling in Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii)". Journal of Experimental Biology. doi:10.1242/jeb.183806. ISSN 1477-9145.

- ^ a b Dong, Emily M.; Allison, W. Ted (2021-01-13). "Vertebrate features revealed in the rudimentary eye of the Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1942): 20202187. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.2187. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 7892416. PMID 33434464.

- ^ a b Jensen, D (1966). "The Pacific Hagfish". Scientific American. 214 (2): 82–90. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0266-82. PMID 5901290. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ a b Zintzen, V.; Rogers, K. M.; Roberts, C. D.; Stewart, A. L.; Anderson, M. J. (2013). "Hagfish feeding habits along a depth gradient inferred from stable isotopes" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 485: 223–234. Bibcode:2013MEPS..485..223Z. doi:10.3354/meps10341.

- ^ a b Barss, William (1993), "Pacific hagfish, Eptatretus stouti, and black hagfish, E. deani: the Oregon Fishery and Port sampling observations, 1988-92", Marine Fisheries Review (Fall, 1993), retrieved April 21, 2010

- ^ a b c Fleury, Aharon G.; MacLennan, Eva M.; Command, Rylan J.; Juanes, Francis (2021). "Reproductive biology and ecology of Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii) and black hagfish (Eptatretus deani)". Journal of Fish Biology. 99 (2): 596–606. Bibcode:2021JFBio..99..596F. doi:10.1111/jfb.14748. ISSN 0022-1112.

- ^ Bucking, Carol. "Digestion under Duress: Nutrient Acquisition and Metabolism during Hypoxia in the Pacific Hagfish". Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ Glover, Chris N.; Wood, Chris M.; Goss, Greg G. (2017-12-01). "Drinking and water permeability in the Pacific hagfish, Eptatretus stoutii". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 187 (8): 1127–1135. doi:10.1007/s00360-017-1097-2. ISSN 1432-136X.

- ^ Clark, Andrew J.; Summers, Adam P. (2007-11-15). "Morphology and kinematics of feeding in hagfish: possible functional advantages of jaws". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (22): 3897–3909. doi:10.1242/jeb.006940. ISSN 1477-9145.

- ^ a b Clark, A. J.; Summers, A. P. (January 2012). "Ontogenetic scaling of the morphology and biomechanics of the feeding apparatus in the Pacific hagfish Eptatretus stoutii". Journal of Fish Biology. 80 (1): 86–99. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03145.x. ISSN 0022-1112.

- ^ a b Cox, Georgina K.; Sandblom, Eric; Richards, Jeffrey G.; Farrell, Anthony P. (2011-04-01). "Anoxic survival of the Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii)". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 181 (3): 361–371. doi:10.1007/s00360-010-0532-4. ISSN 1432-136X. PMID 21085970.

- ^ "Aquarium of the Pacific | Online Learning Center | Pacific Hagfish". www.aquariumofpacific.org. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

- ^ a b c Haney, W. A.; Clark, A. J.; Uyeno, T. A. (2020). "Characterization of body knotting behavior used for escape in a diversity of hagfishes". Journal of Zoology. 310 (4): 261–272. doi:10.1111/jzo.12752. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ a b c Freedman, Calli R.; Fudge, Douglas S. (2017-01-01). "Hagfish Houdinis: biomechanics and behavior of squeezing through small openings". Journal of Experimental Biology. 220 (Pt 5): 822–827. doi:10.1242/jeb.151233. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 28087655.

- ^ a b Uyeno, T.A.; Clark, A.J. (December 2020). "On the fit of skins with a particular focus on the biomechanics of loose skins of hagfishes". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 98 (12): 827–843. doi:10.1139/cjz-2019-0296. ISSN 0008-4301.

- ^ Lim, J.L.; Winegard, T.M. (2015). "Diverse anguilliform swimming kinematics in Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii) and Atlantic hagfish (Myxine glutinosa)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 93 (3): 213–223. Bibcode:2015CaJZ...93..213L. doi:10.1139/cjz-2014-0260. ISSN 0008-4301.

External links

edit- Media related to Eptatretus stoutii at Wikimedia Commons