This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

Oskar Schindler's Enamel Factory (Polish: Fabryka Emalia Oskara Schindlera) is a former metal item factory in Kraków. It now hosts two museums: the Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków, on the former workshops, and a branch of the Historical Museum of the City of Kraków, situated at ul. Lipowa 4 (4 Lipowa Street) in the district of Zabłocie, in the administrative building of the former enamel factory known as Oskar Schindler's Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik (DEF), as seen in the film Schindler's List.[1][2] Operating here before DEF was the first Malopolska factory of enamelware and metal products limited liability company, instituted in March 1937.

Former office block of Schindler's enamel factory in 2011, now branch of the Historical Museum of Kraków | |

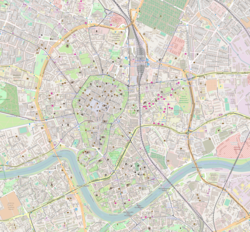

Location within Central Kraków | |

| Established | 1937 |

|---|---|

| Location | Kraków, Poland |

| Coordinates | 50°02′51″N 19°57′42″E / 50.04740°N 19.96175°E |

| Type | History museum |

| Manager | Bartosz Heksel |

| Director | Michał Niezabitowski |

| Curator | Bartosz Heksel |

| Public transit access | Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne w Krakowie how to get there, see external links |

| Website | muzeumkrakowa |

History

editPierwsza Małopolska Fabryka Naczyń Emaliowanych i Wyrobów Blaszanych “Rekord,”Spółka z ograniczoną odpowiedzialnością w Krakowie ('Rekord' First Małopolska Factory of Enamel Vessels and Tinware, Limited Liability Company in Kraków)[3] was established in March 1937[4] by three Jewish entrepreneurs: Michał Gutman from Bedzin, Izrael Kahn from Kraków, and Wolf Luzer Glajtman from Olkusz. The partners leased the production halls from the factory of wire, mesh, and iron products with its characteristic sawtooth roofs, and purchased a plot at ul. Lipowa 4 for their future base. It was then that the following were built: the stamping room where metal sheets were processed, prepared and pressed, the deacidification facility (varnishing) where the vessels were bathed in a solution of sulfuric acid to remove all impurities and grease, and the enamel shop, where enamel was laid in a number of layers: the priming coat first, then the colour, and finally another protective coat.

The ownership of the company changed a number of times, and its financial situation continued to worsen. In June 1939, the company applied for insolvency, which was officially announced by the Regional Court in Kraków.

World War II

editOn 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland and the Second World War broke out. On 6 September, German troops entered Kraków. It was also probably around that time in which Oskar Schindler, a Sudeten German who was a member of the Nazi Party and an agent of the Abwehr, arrived in Kraków. Using the power of the German occupation forces in the capacity of a trustee, he took over the German kitchenware shop on ul. Krakowska, and in November 1939, on the power of the decision of the Trusteeship Authority he took over the receivership of the "Rekord" company in Zabłocie. He also produced ammunition shells, so that his factory would be classed as an essential part of the war effort. He managed to build a subcamp of the Płaszów forced labor camp in the premises where "his" Jews had scarce contact with camp guards.

In January 1940, Schindler changed the name of the factory to Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik - DEF. Initially, non-Jewish Poles predominated among the employed workers. Year by year, the number of Jewish Polish workers recruited through the ghetto wage office increased. Schindler in this respect was initially driven by economic reasons—employing Jews significantly decreased the costs of recruitment, as they did not receive any compensation. For each Polish Jewish worker, the factory director paid a small fee to the SS - 4 złotys per day for a working woman and 5 złotys per day for a working man. The non-Jewish Poles remained employed mainly in administrative positions. The number of Polish Jewish workers increased from over 150 in 1940 to around 1100 in 1944 (this is the sum of workers from three nearby factories, barracked in the sub-camp at DEF).

From the very beginning of the factory's operation, Schindler used part of its profits to provide food for its Jewish workers. The working conditions were difficult, especially at the stands at enamel furnaces and at ladles with sulfuric acid, with which the workers (predominantly women) had direct contact. Other difficulties included low temperatures in the winter, as well as lice epidemics, which caused mainly dysentery, but also typhus. On the other hand, workers at Schindler's factory received bigger food portions than in other factories based on forced labour. During the existence of the ghetto in Podgórze, Jewish workers were led to the factory under the escort of industrial guards (Werkschutzs) or Ukrainians.

When the ghetto was liquidated in 1943, Kraków Jews who escaped death at that time were transferred to the Plaszow labour camp. The distance from the ghetto to Schindler’s Emalia factory had not been very far, but from the Płaszów camp the inmates had to walk several miles. Their workday was already twelve hours long, and Schindler felt sorry for his people.[5] Schindler then applied for a permit to establish a sub-camp of the Plaszow camp on the premises of his factory. He argued that his employees had to walk more than ten kilometers from the camp to the factory every day. Bringing them to the factory would increase its efficiency. His arguments as well as bribes made his plan come to life. In the barracks in Zabłocie, employees of DEF and three neighboring companies producing for the needs of the German army were accommodated. The camp was surrounded by barbed wire, watchtowers were built, and an assembly square was situated between the barracks. The nutritional conditions were much better than in the Płaszow camp, especially due to the cooperation with Polish employees - they contacted people in the city, brought letters and food to the Jewish workers.

The production in the factory and the camp was controlled, and Hauptsturmführer Amon Göth, the commandant of the Plaszow camp, was often a guest here. Thanks to Schindler's efforts, the inspections were not so burdensome for the plant employees. It was only after the Płaszow camp was transformed into a concentration camp in January 1944 that the prisoners from Zabłocie were subject to permanent SS control. The work initially lasted 12 hours in a two-shift system, then 8 hours in a three-shift system. As the eastern front approached Kraków, the Germans began to liquidate the camps and prisons in the east of the General Government. It was then that Oskar Schindler decided to evacuate the factory with its employees to Brünnlitz in Reichsgau Sudetenland, located in the northern part of the Sudetenland in what had been Czechoslovakia (now part of the Czech Republic).[6]

Post-war

editAfter the war, as early as 1946, the factory was nationalized. In the 1948–2002 period, the former DEF facilities were used by Krakowskie Zakłady Elektroniczne Unitra-Telpod (later renamed Telpod S.A.), a company manufacturing telecommunications equipment.[1] Only in 2005, the territory returned to the use of the city of Krakow, and since 2007 the exposition of the ‘Krakow Historical Museum’ called ”Krakow. The period of occupation 1939-1945” has been located here.[7] The museum has the desk and the stairs from the set of Schindler's List as part of the tour.[2]

Gallery

edit-

From 1948 to 2002, the factory was used by Unitra-Telpod.

-

Museum building

-

Entrance area of the factory in 2013

-

Photos of survivors

-

Desk of Oskar Schindler with a list of Jews saved by him

-

Interior installation of Schindler's List

-

An installation commemorating the destruction of the Kraków ghetto

-

Interactive screen

-

Pre-war signs with street names

-

Reconstruction of the basement where Jews were hidden

-

Part of the permanent exhibition

-

Kaiserpanorama/Fotoplastikon

-

Reconstruction of the tram

-

A burned book – symbol of the ghetto

-

Reconstruction of an apartment in the ghetto

-

The facade of the former Schindler's Factory

-

Historical Museum of the City of Krakow - exhibition

References

edit- ^ a b Strzala, Marek. "Schindler's Factory in Krakow". krakow-info.com. Krakow Info. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Oskar Schindler's Enamel Factory - Kraków". TracesOfWar.com. STIWOT. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Crowe, David (2004). Oskar Schindler : the untold account of his life, wartime activities, and the true story behind the list. Cambridge, Mass.: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3375-X. OCLC 55679121.

- ^ Marszałek, Anna (2014). Fabrika "Èmaliâ" Oskara Šindlera : pytevoditel'. Monika Bednarek, Anna Biedrzycka, Kamil Jurewicz, Aleksander Skoblenko, Krystyna Stefaniak, Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Krakowa. Istoričeskij Muzej Groda Krakova. ISBN 9788375771596. OCLC 909690597.

- ^ Pemper, Mieczysław (2008). The road to rescue : the untold story of Schindler's list. Viktoria Hertling, Marie Elisabeth Müller. New York: Other Press. ISBN 978-1-59051-286-9. OCLC 192134542.

- ^ AB Poland Travel. "Schindler's Factory".

- ^ Chornyi, Maxim (10 March 2019). "DEUTSCHE EMAILWARENFABRIK: Oskar Schindler's Factory today". WAR-DOCUMENTARY.INFO. Retrieved 21 December 2022.