In mathematics, orthogonality is the generalization of the geometric notion of perpendicularity to the linear algebra of bilinear forms.

Two elements u and v of a vector space with bilinear form are orthogonal when . Depending on the bilinear form, the vector space may contain null vectors, non-zero self-orthogonal vectors, in which case perpendicularity is replaced with hyperbolic orthogonality.

In the case of function spaces, families of functions are used to form an orthogonal basis, such as in the contexts of orthogonal polynomials, orthogonal functions, and combinatorics.

Definitions

edit- In geometry, two Euclidean vectors are orthogonal if they are perpendicular, i.e. they form a right angle.

- Two vectors u and v in an inner product space are orthogonal if their inner product is zero.[2] This relationship is denoted .

- A set of vectors in an inner product space is called pairwise orthogonal if each pairing of them is orthogonal. Such a set is called an orthogonal set (or orthogonal system). If the vectors are normalized, they form an orthonormal system.

- An orthogonal matrix is a matrix whose column vectors are orthonormal to each other.

- An orthonormal basis is a basis whose vectors are both orthogonal and normalized (they are unit vectors).

- A conformal linear transformation preserves angles and distance ratios, meaning that transforming orthogonal vectors by the same conformal linear transformation will keep those vectors orthogonal.

- Two vector subspaces and of an inner product space are called orthogonal subspaces if each vector in is orthogonal to each vector in . The largest subspace of that is orthogonal to a given subspace is its orthogonal complement.

- Given a module and its dual , an element of and an element of are orthogonal if their natural pairing is zero, i.e. . Two sets and are orthogonal if each element of is orthogonal to each element of .[3]

- A term rewriting system is said to be orthogonal if it is left-linear and is non-ambiguous. Orthogonal term rewriting systems are confluent.

In certain cases, the word normal is used to mean orthogonal, particularly in the geometric sense as in the normal to a surface. For example, the y-axis is normal to the curve at the origin. However, normal may also refer to the magnitude of a vector. In particular, a set is called orthonormal (orthogonal plus normal) if it is an orthogonal set of unit vectors. As a result, use of the term normal to mean "orthogonal" is often avoided. The word "normal" also has a different meaning in probability and statistics.

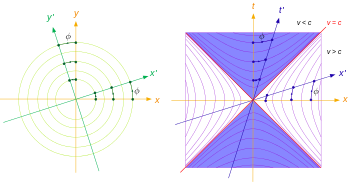

A vector space with a bilinear form generalizes the case of an inner product. When the bilinear form applied to two vectors results in zero, then they are orthogonal. The case of a pseudo-Euclidean plane uses the term hyperbolic orthogonality. In the diagram, axes x′ and t′ are hyperbolic-orthogonal for any given .

Euclidean vector spaces

editIn Euclidean space, two vectors are orthogonal if and only if their dot product is zero, i.e. they make an angle of 90° ( radians), or one of the vectors is zero.[4] Hence orthogonality of vectors is an extension of the concept of perpendicular vectors to spaces of any dimension.

The orthogonal complement of a subspace is the space of all vectors that are orthogonal to every vector in the subspace. In a three-dimensional Euclidean vector space, the orthogonal complement of a line through the origin is the plane through the origin perpendicular to it, and vice versa.[5]

Note that the geometric concept of two planes being perpendicular does not correspond to the orthogonal complement, since in three dimensions a pair of vectors, one from each of a pair of perpendicular planes, might meet at any angle.

In four-dimensional Euclidean space, the orthogonal complement of a line is a hyperplane and vice versa, and that of a plane is a plane.[5]

Orthogonal functions

editBy using integral calculus, it is common to use the following to define the inner product of two functions and with respect to a nonnegative weight function over an interval :

In simple cases, .

We say that functions and are orthogonal if their inner product (equivalently, the value of this integral) is zero:

Orthogonality of two functions with respect to one inner product does not imply orthogonality with respect to another inner product.

We write the norm with respect to this inner product as

The members of a set of functions are orthogonal with respect to on the interval if

The members of such a set of functions are orthonormal with respect to on the interval if

where

is the Kronecker delta.

In other words, every pair of them (excluding pairing of a function with itself) is orthogonal, and the norm of each is 1. See in particular the orthogonal polynomials.

Examples

edit- The vectors are orthogonal to each other, since and .

- The vectors and are orthogonal to each other. The dot product of these vectors is zero. We can then make the generalization to consider the vectors in : for some positive integer , and for , these vectors are orthogonal, for example , , are orthogonal.

- The functions and are orthogonal with respect to a unit weight function on the interval from −1 to 1:

- The functions are orthogonal with respect to Riemann integration on the intervals , or any other closed interval of length . This fact is a central one in Fourier series.

Orthogonal polynomials

editVarious polynomial sequences named for mathematicians of the past are sequences of orthogonal polynomials. In particular:

- The Hermite polynomials are orthogonal with respect to the Gaussian distribution with zero mean value.

- The Legendre polynomials are orthogonal with respect to the uniform distribution on the interval .

- The Laguerre polynomials are orthogonal with respect to the exponential distribution. Somewhat more general Laguerre polynomial sequences are orthogonal with respect to gamma distributions.

- The Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are orthogonal with respect to the measure

- The Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind are orthogonal with respect to the Wigner semicircle distribution.

Combinatorics

editIn combinatorics, two Latin squares are said to be orthogonal if their superimposition yields all possible combinations of entries.[6]

Completely orthogonal

editTwo flat planes and of a Euclidean four-dimensional space are called completely orthogonal if and only if every line in is orthogonal to every line in .[7] In that case the planes and intersect at a single point , so that if a line in intersects with a line in , they intersect at . and are perpendicular and Clifford parallel.

In 4 dimensional space we can construct 4 perpendicular axes and 6 perpendicular planes through a point. Without loss of generality, we may take these to be the axes and orthogonal central planes of a Cartesian coordinate system. In 4 dimensions we have the same 3 orthogonal planes that we have in 3 dimensions, and also 3 others . Each of the 6 orthogonal planes shares an axis with 4 of the others, and is completely orthogonal to just one of the others: the only one with which it does not share an axis. Thus there are 3 pairs of completely orthogonal planes: and intersect only at the origin; and intersect only at the origin; and intersect only at the origin.

More generally, two flat subspaces and of dimensions and of a Euclidean space of at least dimensions are called completely orthogonal if every line in is orthogonal to every line in . If then and intersect at a single point . If then and may or may not intersect. If then a line in and a line in may or may not intersect; if they intersect then they intersect at .[8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. p. 58. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- ^ "Wolfram MathWorld".

- ^ Bourbaki, "ch. II §2.4", Algebra I, p. 234

- ^ Trefethen, Lloyd N. & Bau, David (1997). Numerical linear algebra. SIAM. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-89871-361-9.

- ^ a b R. Penrose (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. pp. 417–419. ISBN 978-0-679-77631-4.

- ^ Hedayat, A.; et al. (1999). Orthogonal arrays: theory and applications. Springer. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-387-98766-8.

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973) [1948]. Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). New York: Dover. p. 124.

- ^ P.H.Schoute: Mehrdimensionale Geometrie. Leipzig: G.J.Göschensche Verlagshandlung. Volume 1 (Sammlung Schubert XXXV): Die linearen Räume, 1902.[page needed]