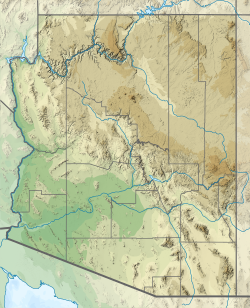

Oak Flat (Western Apache: Chíchʼil Bił Dagoteel, Navajo: Chéchʼil Bił Dahoteel) is in Pinal County about 40 miles (64 km) east of Phoenix in the Tonto National Forest, a high desert setting at 3,900 feet (1,200 m) elevation. The land is sacred to Native Americans from the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation and many other Arizona tribes. This federally-managed area is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and features a National Forest Service public campground. The landscape includes Apache Leap cliff, the mesa of Oak Flat, and Devil's Canyon (Apaches refer to it as Ga'an Canyon, or "Angels Canyon"), all of which have long been popular with hikers, birders, climbers, off-roaders, hunters, and members of the area's indigenous tribes. Oak Flat has been subject to attempts by the federal government to exchange the site for lands owned by mining interests since 2002, against the wishes of the San Carlos Apache tribe.

Oak Flat

| |

|---|---|

Apache Leap cliff | |

| Coordinates: 33°18′29″N 111°02′49″W / 33.308°N 111.047°W | |

| Location | Tonto National Forest |

| Native name |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.7 square miles (17 km2)[1] |

| Website | Official website |

Chíchʼil Bił Dagoteel (Oak Flat Campground) | |

Emory oak trees at Oak Flat | |

| Location | Tonto National Forest |

| NRHP reference No. | 16000002 |

| Added to NRHP | March 4, 2016 |

Description

editAs a "blessed place" where Ga'an — guardians or messengers between the people and Usen, the creator — dwell, Apaches have lived on, worshipped on and cared for this site since before recorded history. They continue to hold important ceremonies there and gather medicinal plants.[2] The area contains petroglyphs and historic and prehistoric sites.[3] President Dwight D. Eisenhower protected the area from mining during an expansion of the Tonto National Forest in 1955. In an 1852 treaty, the U.S. government promised to protect Oak Flat in perpetuity. Oak Flat is a popular destination, for both campers and rock climbers.[4]

Proposed mine

editResolution Copper (RC), a joint venture owned by Rio Tinto and BHP, has proposed conducting underground mining of a copper-molybdenum deposit located 5,000 to 7,000 feet (1,500 to 2,100 m) below the ground surface. The company estimates that the mine would take approximately 10 years to construct and would have an operational life of approximately 40 years which would be followed by 5 to 10 years of reclamation activities.[5]: B-5 In 2014, just hours before the vote on the NDAA, Senator John McCain added a land exchange deal to the bill, which President Barack Obama signed. The Act cleared the way for the land swap in which Resolution Copper would receive 2,422 acres (980 ha) of National Forest land in exchange for deeding to the federal government 5,344 acres (2,163 ha) of private land.[6] An independent appraisal of the exchanged lands found that the value of lands Resolution Copper has offered for Oak Flat is about $7 million, while the Oak Flat parcel is valued at over $112 billion.

McCain and Flake's rider was Section 3003 of the NDAA, titled "Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act", which would allow RC to develop and operate an underground copper mine 7,000 ft (2,100 m) deep in the publicly owned Tonto National Forest near Superior, Arizona. The mine would excavate an area set aside in 1955 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower during an expansion of the Tonto National Forest. The land contains more than 2,400 acres (970 ha) of the Oak Flat Campground, an area dotted with petroglyphs and historic and prehistoric sites.[3] The former San Carlos Apache tribal chairman Wendsler Nosie Sr. said of the Act's rider: “This is Congressional politics at its worse, a hidden agenda that destroys human rights and religious rights."[7]

The San Carlos Apache Tribe, under the leadership of Chairman Terry Rambler, has led a strong opposition to the RC land exchange. Both the National Audubon Society in Tucson and the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club in Arizona along with the National Congress of American Indians have joined in the fight to Resolution's land grab.[3] Native American groups and conservationists worry about the impact to surrounding areas, including the steep cliffs at Apache Leap.[8] James Anaya, former United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, said that without community and tribal support, Rio Tinto should abandon its Resolution Copper mining project.[9] United States Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell said she was "profoundly disappointed with the Resolution Copper provision, which has no regard for lands considered sacred by nearby Indian tribes".[10]

By January 2015, over 104,000 had signed a petition to President Obama titled "We the People|Stop Apache Land Grab". Jodi Gillette, Special Assistant to the President for Native American Affairs, quickly gave an official White House response, vowing that the Obama administration would work with Resolution Copper's parent company Rio Tinto to determine how to work with the tribes to preserve their sacred areas.[11] Scientists warned that the mining project would create a large sinkhole about 2 miles (3.2 km) wide and 1,100 feet (340 m) deep, and would deplete and contaminate Arizona's already limited groundwater supply.[12]

In March 2016, the Forest Service added Oak Flat to the National Register of Historic Places.[13][14] Arizona Republican Congressman Paul Gosar, who has characterized the dispute with the San Carlos Apache as "bogus," condemned the Historic Places designation by the Obama administration and the Forest Service as "sabotaging an important mining effort."[15]

The project has not met all federal surface water and groundwater requirements, yet the Forest Service under the Trump administration rushed the environmental analysis despite the impacts described according to a draft environmental impact statement released in late 2019 by the U.S. Forest Service. This report did not include adequate studies of impacts to the area nor did it consider any alternatives to the plans for the mine. In protest, hundreds of Apache tribe members and supporters walked for four days in February 2020 from San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation to Oak Flat, a distance of 45 miles (72 km). The march was sixth in an annual series.[16]

President Biden issued the Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships in January 2021.[17] The final environmental impact statement was withdrawn by the United States Forest Service in March. Citing the memorandum, the Forest Service said they need more time to fully understand concerns raised by the tribes.[1] On March 18 that year, Representative Raúl Grijalva reintroduced the Save Oak Flat Act for the fourth time, which would repeal the mandate to transfer the land transfer of Oak Flat to Resolution Copper.[18]

References

edit- ^ a b Miller, Emily McFarlan (March 1, 2021). "US Forest Service temporarily halts transfer of Native American sacred site Oak Flat". Religion News Service. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Molina, Alejandra; Miller, Emily McFarlan (March 16, 2021). "Why Oak Flat in Arizona is a sacred space for the Apache and other Native Americans". National Catholic Reporter. Religion News Service. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c "San Carlos Apache Tribe Announces Towns of Superior and Queen Valley Join Opposition to H.R. 687 Southeast Conservation and Land Exchange Act of 2013". NewsRx (Press release). April 7, 2013.

- ^ Moran, Benedict (March 7, 2021). "In Arizona, a struggle over a sacred site of the Apache tribe". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Apache Leap Special Management Area Management Plan (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture: Forest Service: Tonto National Forest: Globe Ranger District (Report). August 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Arizona Geology, “Resolution copper land swap bill signed into law,” 23 Dec. 2014.

- ^ "Once Again, The Fight for Religious Freedom in America Begins". The Apache Messenger. December 22, 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Bregel, Emily (December 11, 2014). "Apache Tribe Distressed by Privatization of Sacred Land". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Anaya, James (December 28, 2014). "Copper Mine Will Hurt Tribes and the Environment". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ U.S. Department of the Interior (December 9, 2014). "Statement by Interior Secretary Sally Jewell on the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015". Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ "White House Responds to 'Stop Apache Land Grab' Petition". Indian Country Today Media Network. January 13, 2015. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "This land is sacred to the Apache, and they are fighting to save it". Washington Post. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Oak Flats Listed on National Register of Historic Places". DAILY KOS. March 11, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ Chí'chil Biłdagoteel Historic District (PDF) (Report). National Park Service: National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. United States Forest Service. December 2, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Congressman Gosar Claims Oak Flat Has Never Been a Sacred Site, Wants to Kick Out Apache Stronghold Protesters". Tucson Daily. March 16, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ O'Brien, Brendan (February 28, 2020). "Apache tribe marches to protect sacred Arizona site from copper mine". Reuters. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships". The White House. January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Sahar Akbarzai. "Arizona Democrat reintroduces bill to protect sacred Apache site from planned copper mine". CNN. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

External links

edit- Resolution Copper Mine and Land Exchange Project Environmental Impact Statement, United States Department of Agriculture: Tonto National Forest