The northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) is one of two species of elephant seal (the other is the southern elephant seal). It is a member of the family Phocidae (true seals). Elephant seals derive their name from their great size and from the male's large proboscis, which is used in making extraordinarily loud roaring noises, especially during the mating competition. Sexual dimorphism in size is great. Correspondingly, the mating system is highly polygynous; a successful male is able to impregnate up to 50 females in one season.

| Northern elephant seal Temporal range: Pleistocene-recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Male (bull), female (cow) and pup | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Phocidae |

| Genus: | Mirounga |

| Species: | M. angustirostris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mirounga angustirostris (Gill, 1866)

| |

| |

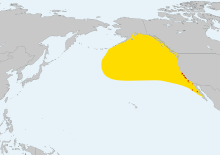

| Distribution of the northern elephant seal (red: breeding colonies; yellow: non-breeding individuals) | |

Description

editThe huge male northern elephant seal typically weighs 1,500–2,300 kg (3,300–5,100 lb) and measures 4–5 m (13–16 ft), although some males can weigh up to 3,700 kg (8,200 lb).[3] Females are much smaller and can range from 400 to 900 kg (880 to 1,980 lb) in weight, or roughly a third of the male's bulk, and measure from 2.5 to 3.6 m (8.2 to 11.8 ft).[4] The bull southern elephant seals are, on average, larger than those in the northern species, but the females in both are around the same size, indicating the even higher level of sexual dimorphism in the southern species.[5] Northern elephant seals typically live for around nine years.[6]

Pups are born with dark, almost black fur that they shed after weaning to turn silvery grey. As they develop, both juveniles and adults go through a molting period in which their initially black fur is replaced with a coat that ranges from silver to deep grey, finally fading to tan. Adult males' necks and chests are furless and have a speckled pattern of pink, white, and light brown. This the consequence of thicker, calloused skin that builds a protective shield in preparation for fights they participate in during the mating season. [7] [8]

The eyes are large, round, and black. The width of the eyes and a high concentration of low-light pigments suggest sight plays an important role in the capture of prey. Like all seals, elephant seals have atrophied hind limbs whose underdeveloped ends form the tail and tail fin. Each of the "feet" can deploy five long, webbed fingers. This agile, dual palm is used to propel water. The pectoral fins are used little while swimming.[citation needed] While their hind limbs are unfit for locomotion on land, elephant seals use their fins as support to propel their bodies. They are able to propel themselves quickly — as fast as 8 kilometres per hour (4.3 kn; 5.0 mph) — in this way for short-distance travel, to return to water, catch up with a female or chase an intruder.[citation needed]

Like other seals, elephant seals' bloodstreams are adapted to the cold in which a mixture of small veins surrounds arteries capturing heat from them. This structure is present in extremities such as the hindlimbs.[citation needed]

A unique characteristic of the northern elephant seal is that it has developed the ability to store oxygenated red blood cells within its spleen. In a 2004 study researchers used MRI to observe physiological changes of the spleens of five seal pups during simulated dives. By three minutes, the spleens on average contracted to a fifth of their original size, indicating a dive-related sympathetic contraction of the spleen. Also, a delay was observed between contraction of the spleen and increased hematocrit within the circulating blood, and attributed to the hepatic sinus. This fluid-filled structure is initially expanded due to the rush of RBC from the spleen and slowly releases the red blood cells into the circulatory system via a muscular vena caval sphincter found on the cranial aspect of the diaphragm. This ability to slowly introduce RBC into the blood stream is likely to prevent any harmful effects caused by a rapid increase in hematocrit.[9]

Range and ecology

editThe northern elephant seal lives in the eastern Pacific Ocean. They spend most of their time at sea, and usually only come to land to give birth, breed, and molt. These activities occur at rookeries that are located on offshore islands or remote mainland beaches. The majority of these rookeries are in California and northern Baja California, ranging from Point Reyes National Seashore, California to Isla Natividad, Mexico.[10] Significant breeding colonies exist at Channel Islands, Año Nuevo State Reserve, Piedras Blancas Light, Morro Bay State Park and the Farallon Islands in the US,[11] and Isla Guadalupe, Isla Benito del Este and Isla Cedros in Mexico.[11] In recent decades the breeding range has extended northwards. In 1976 the first pup was found on Point Reyes and a breeding colony established there in 1981.[12] Since the mid-1990s some breeding has been observed at Castle Rock in Northern California and Shell Island off Oregon,[13] and in January 2009 the first elephant seal births were recorded in British Columbia at Race Rocks.[14] The California breeding population is now demographically isolated from the population in Baja California.[11]

Northern elephant seals exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism in their feeding behaviours. When the males leave their rookeries, they migrate northwards to their feeding grounds along the continental shelf from Washington to the western Aleutians in Alaska.[15][16] The males mostly feed on benthic organisms on the ocean floor.[15] When the females leave their rookeries, they head north or west into open ocean, and forage across a large area in the northeastern Pacific.[15] They have been recorded as far west as Hawaii.[15] Female elephant seals feed mainly on pelagic organisms in the water column.[15]

Vagrant elephant seals possibly appear on tropical regions such as at Mariana Islands.[17] Historical occurrences of elephant seal presence, residential or occasional, in western North Pacific are fairly unknown. There have been two records of vagrants visiting to Japanese coasts; a male on Niijima in 1989[18] and a young seal on beaches in Hasama, Tateyama in 2001.[19] A 2.5-metre (8 ft 2 in) female was found on Sanze beach, Tsuruoka, Yamagata in October 2017, making it the first record from Sea of Japan. This individual was severely weakened but showing signs of recovery after receiving medications at Kamo Aquarium, and the aquarium is[when?] discussing whether or not to release her.[20] Some individuals have been observed on the coast of northeast Asia. Certain individuals established haul-out sites at the Commander Islands in the early 2000s; however, due to aggressive interactions with local Steller sea lions, long-term colonization is not expected.[21][22]

Female elephant seals forage in the open ocean, while male elephant seals forage along the continental shelf.[15] Males usually dive straight down to the ocean floor and stay at the bottom foraging for benthic prey.[15] The females hunt for pelagic prey in the open ocean, and dive deeper — up to 1,735 metres (5,692 ft), though on average about 500 metres (1,640 ft) — and stay down longer than the males.[23][15] Female elephant seals have been tagged and found to dive almost continuously for 20 hours or more a day, mostly in 400-to-600-metre (1,310 to 1,970 ft) deep water, where small fish are abundant.[24]

Northern elephant seals eat a variety of prey, including mesopelagic fish such as myctophids, deep-water squid, Pacific hake, pelagic crustaceans, relatively small sharks, rays, and ratfish.[25][16][26] Octopoteuthis deletron squid are a common prey item, one study found this species in the stomachs of 58% of individuals sampled off the coast of California.[27] A female northern elephant seal was documented in 2013 by a deep sea camera at a depth of 894 m (2,933 ft), where she consumed a Pacific hagfish, slurping it up from the ocean floor. The event was reported by a Ukrainian boy named Kirill Dudko, who further reported the find to scientists in Canada.[28] Elephant seals do not need to drink, as they get their water from food and metabolism of fats.

While hunting in the dark depths, elephant seals seem to locate their prey at least partly by vision; the bioluminescence of some prey animals can facilitate their capture. Elephant seals do not have a developed a system of echolocation in the manner of cetaceans, but their vibrissae, which are sensitive to vibrations, are assumed to play a role in search of food. Males and females differ in diving behavior. Males tend to hug the continental shelf while making deep dives and forage along the bottom,[15] while females have more jagged routes and forage in the open ocean.[15] Elephant seals are prey for orcas and great white sharks. Both are most likely to hunt pups, and seldom hunt large bull elephant seals, but have taken seals of all ages. The shark, when hunting adults, is most likely to ambush a seal with a damaging bite and wait until it is weakened by blood loss to finish the kill.[29]

Social behavior and reproduction

editNorthern elephant seals return to their terrestrial breeding ground in December and January, with the bulls arriving first. The bulls haul out on isolated or otherwise protected beaches, typically on islands or very remote mainland locations. It is important that these beach areas offer protection from the winter storms and high surf wave action.[30] The bulls engage in fights of supremacy to determine which few bulls will achieve a harem.[31][32]

After the males have arrived on the beach, the females arrive to give birth. Females fast for five weeks and nurse their single pup for four weeks; in the last few days of lactation, females come into estrus and mate.[33] Mating behavior relates to a social hierarchy, and stronger males are considered higher rank than those smaller and weaker.[34] In this polygynous society, a high-ranking bull can have a harem of 30–100 cows, depending on his size and strength. Males unable to establish harems will wait on the periphery, and will try to mount nearby females. Dominant bulls will disrupt copulations of lower-ranking bulls. They can mount females without interference, but commonly break off to chase off rivals.[31] While fights are not usually to the death, they are brutal and often with significant bloodshed and injury; however, in many cases of mismatched opponents, the younger, less capable males are simply chased away, often to upland dunes. In a lifetime, a successful bull could easily sire over 500 pups. Most copulations in a breeding colony are done by only a small number of males and the rest may never be able to mate with a female.[32] Copulation is most often on land, and takes roughly five minutes.[34] Pups are sometimes crushed during battles between bulls.[30][32]

After arrival on shore, males fast for three months, and females fast for five weeks during mating and when nursing their pups. The gestation period is about 11 months. One study observed the vast majority of births to take place at night, and in the aforementioned harems. Immediately after birth, a female will turn to her pup and emit a warbling vocalization to attract them, and will continue to throughout the nursing period.[35] Sometimes, a female can become very aggressive after giving birth and will defend her pup from other females. Such aggression is more common in crowded beaches.[36] While most females nurse their own pups and reject nursings from alien pups, some do accept alien pups with their own. An orphaned pup may try to find another female to suckle and some are adopted, at least on Año Nuevo Island.[30][33] Some pups, known as super weaners, may grow to exceptionally large sizes by nursing from other females in addition to their mothers.[37][38] Pups nurse about four weeks and are weaned abruptly before being abandoned by their mother, who heads out to sea within a few days. Pups gain weight rapidly during the nursing period, and weigh 300–400 pounds (136–181 kg) on average upon being weaned.[35] Left alone, weaned pups will gather into groups and stay on shore for 12 more weeks. The pups learn how to swim in the surf and eventually swim farther to forage. Thus, their first long journey at sea begins.

Elephant seals communicate though various means. Males will threaten each other with the snort, a sound caused by expelling air though their probosces, and the clap-trap, a loud, clapping sound comparable to the sound of a diesel engine. Pups will vocalize when stressed or when prodding their mothers to allow them to suckle. Females make an unpulsed attraction call when responding to their young, and a harsh, pulsed call when threatened by other females, males or alien pups. Elephant seals produce low-frequency sounds, both substrate-borne and air-borne. These sounds help maintain social hierarchy in crowded or noisy environments and reduce energy consumption when fasting.[39]

History and status

editBeginning in the 18th century, northern elephant seals were hunted extensively, almost to extinction by the end of the 19th century, being prized for oil made from their blubber, and the population may have fallen as low as only 20-40 individuals.[1] In 1874, Charles Melville Scammon recorded in Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast of America, that an 18-foot (5.5 m) long bull caught on Santa Barbara Island yielded 210 US gallons (795 L; 175 imp gal) of oil.[40] They were thought to be extinct in 1884 until a remnant population of eight individuals was discovered on Guadalupe Island in 1892 by a Smithsonian expedition, who promptly killed several for their collections.[41] The elephant seals managed to survive, and were finally protected by the Mexican government in 1922. Since the early 20th century, they have been protected by law in both Mexico and in the United States. Subsequently, the U.S. protection was strengthened after passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, and numbers have now recovered to over 100,000.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, a genetic bottleneck experienced by northern elephant seals during the nineteenth century made them more susceptible to disease, environmental changes and pollution.[42][43] Such a small initial population of around 20-40 also meant that extensive inbreeding occurred within the species, leading to a whole other onset of issues.[44] Such issues from the bottleneck a sharp loss of genetic diversity and increased homozygosity in the surviving population, and also a decreased number of haplogroups.[45] In addition to this, there was also a substantial increase in the rate of asymmetry within the animals' skulls.[44]

In California, the population is continuing to grow at around 6% per year, and new colonies are being established; they are now probably limited mostly by the availability of haul-out space. Their breeding was probably restricted to islands, before large carnivores were exterminated or prevented from reaching the side of the ocean.[46] Numbers can be adversely affected by El Niño events and the resultant weather conditions, and the 1997–98 El Niño may have caused the loss of about 80% of that year's pups. Presently, the northern elephant seal is protected under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act and has a fully protected status under California law (California Fish and Game Code [FGC] § 4700).

While the population is rising in the state of California, some colonies farther south are experiencing declining populations, likely due to rising sea and air temperatures. In Baja California, the two largest colonies, in Guadalupe and San Benito, have seen consistently declining numbers for the past two decades. Seeing as populations farther north are consistently increasing, it has been hypothesized that this discrepancy is due to a change in migration patterns.[47] As sea and air temperatures rise, Northern elephant seals may not be migrating as far south as they have previously. The climate is expected to continue warming, and southern populations are expected to continue falling.[47]

Populations of rookery sites in California have increased during the past century.[1] At Año Nuevo State Park, for example, no individuals were observed whatsoever until 1955; the first pup born there was observed in the early 1960s. Currently, thousands of pups are born every year at Año Nuevo, on both the island and mainland. The growth of the site near San Simeon has proved even more spectacular; no animals were there prior to 1990. Currently, the San Simeon site hosts more breeding animals than Año Nuevo State Park during winter season.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Hückstädt, L. (2015). "Mirounga angustirostris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T13581A45227116. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T13581A45227116.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Beer, Encyclopedia of North American Mammals: An Essential Guide to Mammals of North America. Thunder Bay Press (2004), ISBN 978-1-59223-191-1.

- ^ Mirounga angustirostris. Northern Elephant Seal. A 22 ft (7 m) individual was reported by Scammon in 1874. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

- ^ Novak RM (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ^ "Elephant Seals | National Geographic". National Geographic Society. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ "Northern Elephant Seal". NOAA Fisheries. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Lifestyle of Northern Elephant Seals". Earthguide at UCSD. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Thornton SJ, Hochachka PW (2004). "Oxygen and the diving seal" (PDF). Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 31 (1): 81–95. PMID 15233163. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Stewart BS, Yochem PK, Huber HR, DeLong RL, Jameson RJ, Sydeman WJ, Allen SG, Le Boeuf BJ (1994). "History and present status of the Northern elephant seal population". In Le Boeuf BJ, Laws RM (eds.). Elephant Seals: Population Ecology, Behavior, and Physiology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 29–48. ISBN 978-0520083646.

- ^ a b c U.S. Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments: 2007 (NMFS-SWFSC-414). (PDF) . Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- ^ Allen SG, Peaslee SC, Huber HR (1989). "Colonization by Northern Elephant Seals of the Point Reyes Peninsula, California". Marine Mammal Science. 5 (3): 298–302. Bibcode:1989MMamS...5..298A. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1989.tb00342.x.

- ^ Hodder J, Brown RF, Cziesla C (1998). "The northern elephant seal in Oregon: A pupping range extension and onshore occurrence". Marine Mammal Science. 14 (4): 873–881. Bibcode:1998MMamS..14..873H. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00772.x.

- ^ Elephant Seal birth of baby ninene Archived 4 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Racerocks.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Le Boeuf B, Crocker D, Costa D, Blackwell S, Webb P (2000). "Foraging ecology of northern elephant seals". Ecological Monographs. 70 (3): 353–382. doi:10.1890/0012-9615(2000)070[0353:feones]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 2657207.

- ^ a b Condit R, Le Boeuf BJ (1984). "Feeding Habits and Feeding Grounds of the Northern Elephant Seal". J. Mammal. 65 (2): 281–290. doi:10.2307/1381167. JSTOR 1381167.

- ^ "Marine Protected Species of the Mariana Islands" (PDF). National Marine Fisheries Service. January 2015.

- ^ "Whale appearance!". Niijima.jp. 4 March 2011.

- ^ "アザラシ". Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014. retrieved on 14-05-2015

- ^ Kahoku Shimpō (2017). "Goron kinta elephant seal on the beach protected for the first time on the Japan Sea side" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ Kuznetsov V.B. (2004). "Fluctuations of dolphins' abundance in northern and northeastern parts of the Black Sea according to polling data (1995–2003)" (PDF). Marine Mammals of the Holarctic.

- ^ "North Sea Elephant Mirounga angustirostris Gill, 1866". FGBU State Nature Biosphere Reserve (in Russian).

- ^ Robinson PW, Costa DP, Crocker DE, Gallo-Reynoso JP, Champagne CD, Fowler MA, Goetsch C, Goetz KT, Hassrick JL, Hückstädt LA, Kuhn CE, Maresh JL, Maxwell SM, McDonald BI, Peterson SH, Simmons SE, Teutschel NM, Villegas-Amtmann S, Yoda K (15 May 2012). "Foraging behavior and success of a mesopelagic predator in the northeast Pacific Ocean: insights from a data-rich species, the northern elephant seal". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e36728. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736728R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036728. PMC 3352920. PMID 22615801.

- ^ Pain, Stephanie (31 May 2022). "Call of the deep". Knowable Magazine. Annual Reviews. doi:10.1146/knowable-052622-3. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Goetsch C, Conners MG, Budge SM, Mitani Y, Walker WA, Bromaghin JF, Simmons SE, Reichmuth CJ, Costa DP (2018). "Energy-rich mesopelagic fishes revealed as a critical prey resource for a deep-diving predator using Quantitative Fatty Acid Signature Analysis". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5: 430. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00430.

- ^ Morejohn GV, Beltz DM (1970). "Contents of the stomach of an elephant seal". Journal of Mammalogy. 51 (1): 173–174. doi:10.2307/1378554. JSTOR 1378554.

- ^ Le Beouf BJ, Laws LM (1994). Elephant Seals: Population ecology, behavior, and physiology. University of California Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-520-08364-6.

- ^ Outdoor Archived 28 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. GrindTV. Retrieved on 2014-03-18.

- ^ White Sharks – Carcharodon carcharias. Pelagic Shark Research Foundation.

- ^ a b c Riedman ML, Le Boeuf BJ (1982). "Mother-pup separation and adoption in northern elephant seals". Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 11 (3): 203–213. Bibcode:1982BEcoS..11..203R. doi:10.1007/BF00300063. JSTOR 4599535. S2CID 2332005.

- ^ a b Leboeuf BJ (1972). "Sexual behavior in the Northern Elephant seal Mirounga angustirostris". Behaviour. 41 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1163/156853972X00167. JSTOR 4533425. PMID 5062032.

- ^ a b c Le Boeuf BJ (1974). "Male-male competition and reproductive success in elephant seals". Am. Zool. 14: 163–176. doi:10.1093/icb/14.1.163.

- ^ a b Le Boeuf BJ, Whiting RJ, Gantt RF (1972). "Perinatal behavior of northern elephant seal females and their young". Behaviour. 43 (1): 121–56. doi:10.1163/156853973x00508. JSTOR 4533472. PMID 4656181.

- ^ a b Leboeuf, Burney J. (1 January 1972). "Sexual Behavior in the Northern Elephant Seal Mirounga Angustirostris". Behaviour. 41 (1–2): 1–26. doi:10.1163/156853972X00167. ISSN 0005-7959. PMID 5062032.

- ^ a b Le Boeuf, Burney J.; Whiting, Ronald J.; Gantt, Richard F. (1972). "Perinatal Behavior of Northern Elephant Seal Females and Their Young". Behaviour. 43 (1/4): 121–156. ISSN 0005-7959. JSTOR 4533472.

- ^ Christenson TE, Le Boeuf BJ (1978). "Aggression in the Female Northern Elephant Seal, Mirounga angustirostris". Behaviour. 64 (1/2): 158–172. doi:10.1163/156853978X00495. JSTOR 4533866. PMID 564691.

- ^ Reiter, Joanne; Stinson, Nell Lee; Le Boeuf, Burney J. (1978). "Northern Elephant Seal Development: The Transition from Weaning to Nutritional Independence". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 3 (4): 337–367. Bibcode:1978BEcoS...3..337R. doi:10.1007/BF00303199. ISSN 0340-5443. JSTOR 4599180. S2CID 13370085.

- ^ "Elephant Seals". California State Parks. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Steward BS, Huber HR (1993). "Mirounga angustirostris" (PDF). Mammalian Species (449): 1–10. doi:10.2307/3504174. JSTOR 3504174. S2CID 254007992. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2014.

- ^ Scammon CM (2007). The marine mammals of the northwestern coast of North America: together with an account of the American whale-fishery. Heyday Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-59714-061-4.

- ^ Busch BC (1987). The War Against the Seals: A History of the North American Seal Fishery. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-7735-0610-7.

- ^ Hoelzel AR, Fleischer R, Campagna C, Le Boeuf BJ, Alvord G (2002). "Impact of a population bottleneck on symmetry and genetic diversity in the northern elephant seal". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 15 (4): 567–575. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00419.x. S2CID 85821330.

- ^ Weber DS, Stewart BS, Garza JC, Lehman N (October 2000). "An empirical genetic assessment of the severity of the northern elephant seal population bottleneck". Current Biology. 10 (20): 1287–90. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1287W. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00759-4. PMID 11069110. S2CID 14943019.

- ^ a b HOELZEL, A. RUS (September 1999). "Impact of population bottlenecks on genetic variation and the importance of life-history; a case study of the northern elephant seal". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 68 (1–2): 23–39. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1999.tb01156.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ Frankham R, Ballou JD, Briscoe DA, McInness KH (2013). Introduction to Conservation Genetics (2nd ed.). Cambridge Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87847-0.

- ^ Le Boeuf, Burney J.; Kaza, Stephanie, eds. (1981). "Ch. 7 "Mammals"". The Natural History of Ano Nuevo. Boxwood Press. ISBN 978-0910286770.

- ^ a b García-Aguilar, María C.; Turrent, Cuauhtémoc; Elorriaga-Verplancken, Fernando R.; Arias-Del-Razo, Alejandro; Schramm, Yolanda (15 February 2018). "Climate change and the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) population in Baja California, Mexico". PLOS ONE. 13 (2): e0193211. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1393211G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193211. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5814045. PMID 29447288.