New Brighton Tower was a steel lattice observation tower at New Brighton in the town of Wallasey, Cheshire (now in the Borough of Wirral, in Merseyside), England. It stood 567 feet (173 m) high, and was the tallest building in Great Britain when it opened some time between 1898 and 1900. Neglected during the First World War and requiring renovation the owners could not afford, dismantling of the tower began in 1919, and the metal was sold for scrap. The building at its base, housing the Tower Ballroom, continued its use until damaged by fire in 1969.

| New Brighton Tower | |

|---|---|

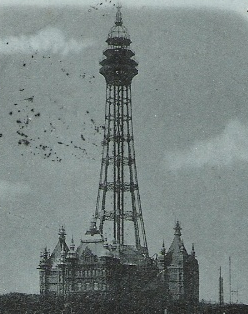

New Brighton Tower and the four-storey red-brick Tower Building | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Observation tower |

| Architectural style | Steel lattice design |

| Location | New Brighton, Wallasey, Cheshire (now Merseyside), England, UK |

| Coordinates | 53°26′12.37″N 3°02′11.03″W / 53.4367694°N 3.0363972°W |

| Completed | 1898–1900 |

| Demolished | Tower in 1919–21 and Tower Building in 1969 |

| Cost | £120,000 |

| Owner | New Brighton Tower and Recreation Company |

| Height | |

| Roof | 567 ft (173 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 4 |

| Lifts/elevators | 4 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Maxwell and Tuke |

| Developer | New Brighton Tower Estates Syndicate |

| Structural engineer | Andrew Handyside and Co. |

| Main contractor |

|

The tower was set in large grounds, which included a boating lake, a funfair, gardens, and a sports ground. The sports ground housed, at different times, a football team, an athletics track and a motorcycle speedway track. The Beatles played at the Tower Ballroom 27 times, more than at any other venue in the United Kingdom except the Cavern Club in nearby Liverpool.

Location

editIn 1830, James Atherton purchased much of the land at Rock Point,[1] in the north-east corner of Wallasey opposite the city and docks of Liverpool.[2] He renamed it New Brighton and organised its development as a tourist destination.[3] In July 1896 a new group, the New Brighton Tower and Recreation Company, with a share capital of £300,000, purchased the estate of the demolished Rock Point House.[4] Their ambition was to create an observation tower in the grounds, designed to rival the Blackpool Tower,[5] while using the remaining grounds to create a more "elegant" atmosphere.[2] The New Brighton Tower and Recreation Company had more than 20 acres (8 ha) of land available to construct the tower, which enabled them to include more attractions than at Blackpool Tower.[2]

Construction

editThe company Maxwell and Tuke, who had designed Blackpool Tower buildings and Southport Winter Gardens,[6] was responsible for overseeing and supervising the project,[2] despite the deaths in 1893 of the company founders, James Maxwell and William Charles Tuke.[7] The excavations and laying of the foundations for the tower were contracted to William Clapham of Stockport.[2] The primary contractor for the tower was Andrew Handyside and Company, based in Derby.[8]

The ground breaking happened on 22 June 1896,[4] before the formation of the new company, completion of land purchase and announcement of contracts on 26 July 1896.[2] The construction of the steel lattice tower started in July 1897[4] and was completed some time between 1898 and 1900,[9][10] 5 years after the Blackpool Tower had been finished.[11] The grounds were opened before then for a short period in 1897 however.[12] New Brighton Tower was the tallest building in England, standing 567 feet (173 m) tall,[13] and 621 feet (189 m) above sea-level.[14] A total of 1,000 long tons (1,000 t) of mild or low-carbon steel was used,[15] at a cost of £120,000,[4] in contrast to the earlier Blackpool and Eiffel towers, both constructed using wrought iron.[8] The building below the New Brighton Tower, which was to contain the ballroom, was constructed by Peters and Sons of Rochdale.[2] It was a four-storey red-brick building with arched windows and hexagonal, copper-domed turrets.[16]

A series of accidents during the tower's construction resulted in the deaths of six workmen and serious injury to another. Two of the men, Jonathan Richardson and Alexander Stewart, were killed when a crane hook snapped and a girder fell and hit the scaffold platform on which they were standing, causing them to fall to the ground. A third man, John Daly, suffered serious injuries.[17] The other four were killed in separate incidents by falling off the tower structure.[4] A fire on the tower at 172 feet (52 m) in 1898 resulted in the death of a fire-fighter from the New Brighton Fire Brigade.[18] He fell 90 feet (27 m) while walking along a beam 6-inch (150 mm) wide to try and extinguish the flames.[19]

Tower building

editNew Brighton Tower regularly advertised itself as "the highest structure and finest place of amusement in the Kingdom".[20][21] A single entrance fee of one shilling (or a ticket for the summer season, costing 10s 6d)[20] was charged for entrance into the grounds, which included the gardens, the athletic grounds, the ballroom and the theatre. An additional charge of sixpence was levied on those who wished to go to the top of the tower.[4] There was a menagerie within the building, containing Nubian lions,[22] Russian wolves (which had eight cubs in 1914),[23] bears in a bear pit,[24] monkeys, elephants, stags, leopards and other animals.[22] There was also an aviary above the ballroom.[4] The Tower Building also contained a shooting gallery and a billiard saloon with five tables.[4]

Maxwell and Tuke clothed the entertainment buildings in hard-wearing, red Ruabon brick with terracotta and stone dressings, and the plan of the buildings was octagonal, with the Tower, also built on an octagonal plan, at its centre. The roofline of the three-to-four-storey building was dramatic, as four corners of the octagon were emphasised by tall pavilions with steeply pitched roofs topped by cupolas

— Lynn Pearson, The People's Palaces[25]

Tower

editThe tower had four lifts, each capable of reaching the top in 90 seconds[22] and conveying up to 2000 people an hour.[2] The views from the top included the Liverpool skyline, the River Mersey estuary and the River Dee.[2] On a clear day, visitors could see across the Irish Sea to the Isle of Man, along with views of the Lake District and Welsh Mountains.[5] In its first year, the tower attracted up to half a million visitors to the top. At night, the tower was illuminated by fairy lights.[4]

On 7 September 1909, two visitors were left stranded at the top of the tower as the final lift car of the night descended without them. The woman and twelve-year-old child were not noticed during the final round of inspection and so, without a way to communicate with anyone on the ground, they spent the night on the tower until 10 am the following morning. They did not appear too concerned by the ordeal and left without giving their names to officials.[26]

Tower Ballroom

editThe ballroom had a sprung floor and dance band stage. It could accommodate more than a thousand couples dancing and had a separate area for couples to learn the dances before taking to the main floor. It was decorated in white and gold with emblems of Lancashire towns, and had balcony seating for spectators.[4]

The composer Granville Bantock was enlisted as musical director in 1897[27] at the ballroom to provide music each weekday for six hours of ballroom dancing.[28] To begin with, as the tower was being erected, he was in charge of a "semi-military band" that played outdoors with the fear that the tower might fall upon him and his players. Bantock is quoted as saying, "The noise of the riveting of the tower while we were playing ... reminded me of the anvil music in Das Rheingold". Bantock often played for the workmen during their lunch breaks, when they could frequently be heard saying, "play it again, guv'nor".[27]

Soon, Granville had a full orchestra at his disposal, so he convinced the management committee to allow him to give classical concerts on Fridays and Sundays.[27][28] He then embarked on advanced concerts of new composers, as well as his own works.[29] As he had difficulty finding time to practise these works, Bantock used afternoon sessions, in which he was supposed to play dance music, to rehearse his classical pieces.[27] When the classical pieces spread to the afternoon programme, the management felt it was not commercially viable to continue the concerts.[28] After three years at the tower, Bantock was appointed Principal of the School of Music at Birmingham and Midland Institute.[27]

The composer Edward Elgar conducted his Enigma Variations at the New Brighton Tower Ballroom in 1898, the second time he performed the piece.[30] In 1900 he conducted Tchaikovsky's Pathétique symphony at New Brighton Tower.[31]

The interior of the ballroom was completely destroyed by fire in 1956, but it was restored in its original style and reopened two years later.[25]

On 10 November 1961, The Beatles played for an audience of 4,000 people at the New Brighton Tower Ballroom[32] as the headline act of a five-and-a-half-hour concert named Operation Big Beat. Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Remo Four and Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes also performed at the concert.[33] The Beatles played at the venue 27 times, commemorated in a blue plaque erected in New Brighton in 2011.[34] The only British venue The Beatles played at more often was the Cavern Club.[35] Little Richard and the Rolling Stones also performed at the Tower Building.[16]

Tower Theatre

editOn 30 May 1898 the Tower Theatre was opened, sited between the legs of the tower. Capable of accommodating an audience of 2,500,[4] it was the largest theatre in England outside London.[36] Each season at the theatre was different; some years it would show a play or an opera,[4] others it would focus on variety acts such as magicians, comedians[37] and lion tamer Mademoiselle Marguerite, with her seven lions.[4] Wrestling was hosted at the theatre as early as 1903,[38] and had become a weekly event by 1937. When the Americans occupied the site during the Second World War, they used the Tower Theatre to show their own roadshows to the troops.[4]

Grounds

editThe tower's grounds were enclosed by iron railings, and throughout the gardens the roads and paths were illuminated with 30,000 red, white and green fairy lights at night.[4][39] The tower's grounds had a band stand, a dancing platform, a fountain, seal pond[4] and tennis courts.[12] The gardens were separated into wooded areas, rockeries and flower beds.[22] There was a lake in the grounds, which had a 130-foot (40 m) water chute[22] and gondolas[40] with Venetian gondoliers.[39] There were also a number of venues providing refreshments, including a Japanese restaurant that could cater for up to 700 people,[22] the Parisian Tea Garden,[4] the Rock Point Castle restaurant, which could accommodate 400 people, and an Algerian café.[22]

At the grounds of the tower there was a large permanent funfair,[41] with rides including Figure of Eight, Wall of Death, Donkey Derby, The Himalayan Switchback Railway and The Caterpillar. To give easy access from the promenade entrance to the tower, a chair lift was introduced.[42] In 1898–99 an acrobat named Hardy performed for a season at the tower without a safety net and often without a balancing pole on the high wire 100 feet (30 m) above the dancing platform.[43] In 1908 the 'Himalaya Railway' was replaced with a scenic railway.[44]

Tower Athletic Ground

editAn area was set aside within the grounds for athletics, aptly named the Tower Athletic Ground. It consisted of a stadium opened in 1896; the hope was to provide additional entertainment for visitors to the tower in the winter months.[4] The capacity of the grounds varied, but at one point was as high as 100,000, although attendances rarely, if ever, approached that figure.[10]

The New Brighton Tower and Recreation Company formed a football team, New Brighton Tower F.C., and applied for membership to the Lancashire League.[45] The team joined at the start of the 1897–98 season and promptly won the league. The club then applied for election to the Football League. Although they were initially rejected, the league later decided to expand Division Two by four clubs and New Brighton Tower were accepted.[46] They carried on playing until 1901 when the company disbanded the team[47] as they did not gain the fan base they were hoping for and so it was no longer considered financially viable.[45]

The Tower Athletic Grounds was a multi-purpose stadium and ground that could be laid out for athletics field events. The field was encircled by an athletics track surrounded by a banked cycle track, which hosted the World Cycling championships in July 1922.[48] It was the biggest sporting and motorcycling track in the North of England.[24] In 1933, the athletics track was replaced for use every Saturday by motorcycle speedway racing.[49]

Disaster struck the motorcycling in 1911 when T. Henshaw's bike struck six spectators at around 50 miles per hour (80 km/h). This left Henshaw with serious fractures and one woman with a severe brain injury.[50] In another incident on 18 May 1959 five people were injured while watching a motorcycling stunt when a 10-foot (3.0 m) wide section of stands collapsed, causing the spectators to fall 15 feet (4.6 m) to the ground.[51]

On 15 May 1919 a fire destroyed the grandstand.[24] During the Second World War, the United States Army took over the Tower Athletic Grounds as a storage facility for military vehicles to be used in the invasion of France.[4] Following the war the stadium was reopened as the home ground for New Brighton A.F.C., whose Sandheys Park had been requisitioned for housing. They sold it to the Wallasey Housing Corporation in 1977.

Exhibitions

editIn 1900, New Brighton Tower athletic grounds boasted the UK's first visit from a group known as The Ashanti Village, in which 100 West African men, women and children re-created an Ashanti village, produced and sold their wares and performed "war tournaments, songs [and] fetish dances".[52] Although they had arrived, delays meant that they were not set up in time for Whitsun[22] the traditional start of the summer season.[53] As was common at fairgrounds of the time, there was a Bioscope exhibition showing the latest wartime pictures to audiences of up to 2,000.[21] In the summer of 1907 there was a Hale's Tours of the World exhibition in the tower's grounds,[5] consisting of short films shown in a stylised railway carriage with sound effects and movements at the appropriate times.[36]

Closure

editThe tower was closed in 1914 following the outbreak of the First World War, for the duration of which the steel structure was not maintained and consequently became rusty.[4] During the war the government made unsuccessful attempts to buy the tower for its metal. Controversy still surrounds the decision to dismantle the tower after the war ended; some still believe the structure was safe and could have been repaired.[45] Demolition began in 1919 and by 1921 only the ballroom remained.[13] The metal was sold to scrap dealers.[45]

The tower was the tallest structure to be demolished in the UK until 7 September 2016, when a taller chimney at Grain Power Station was demolished.[54]

On 5 April 1969 the ballroom was destroyed by fire,[13] the cause of which is unknown.[16] In place of the tower's grounds, including the athletics ground and stadium, a new housing estate was built, River View Park, which has a community football pitch and swing park.[55] In 1997 Wirral Council made an unsuccessful bid for Millennium funding to build a new tower in New Brighton.[56]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Morley 2012, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Miscellaneous Companies: The New Brighton Tower and Recreation Company, Limited". The Times. 25 July 1896. p. 4. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ Johnstone, Marianne (2005). "New Brighton Tower". Local Historian. 35 (1–4). National Council of Social Service.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "The Tower Grounds". History of Wallasey. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Roberts 2012, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Pearson 1991, p. 85.

- ^ Pearson, Lynn. "Maxwell, James (1838–1893)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 June 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ a b Jackson, Alastair (1998). "The Development of Steel Framed Buildings in Britain 1880–1905". Construction History. 14. The Construction History Society: 24. JSTOR 41601859.

- ^ "New Brighton Tower and Recreation Grounds". The Era. 28 May 1898. p. 19. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Twydell 1995, p. 145.

- ^ "North Wirral Coast" (PDF). Visit Wirral. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ a b "New Brighton Tower and Gardens". Belfast News-Letter. 28 May 1898. p. 6. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Howse, Christopher (24 March 2012). "New fortunes for New Brighton". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Easdown 2009, p. 16.

- ^ The Builder (1896). The Builder. Vol. 71. University of Michigan. p. 159.

- ^ a b c Wheeler 2005, p. 206.

- ^ "Fatal accident at the New Brighton Tower: Two Men Killed". Liverpool Mercury. 14 January 1897. p. 5. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Fire at New Brighton Tower: Terrible Death of a Fireman". Morpeth Herald. 9 April 1898. p. 6. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The New Brighton Tower Fire: Inquest on the deceased fireman". Liverpool Echo. 4 April 1898. p. 3. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "New Brighton Tower". Liverpool Mercury. 21 May 1900. p. 1. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "New Brighton Tower". Liverpool Mercury. 11 April 1900. p. 1. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "New Brighton Tower:Whit-Week Attractions". Liverpool Mercury. 1 June 1900. p. 9. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Untitled". Nelson Evening Mail. 29 July 1914. p. 6. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "News in Brief". The Times. 16 May 1919. p. 9.

- ^ a b Pearson 1991, p. 41.

- ^ "All Night on a Tower". Colonist. 26 October 1909. p. 4. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Granville Bantock". The Musical Times. 50 (50). Musical Times Publications: 13–14. 1 January 1909. doi:10.2307/907123. JSTOR 907123.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 1960, p. 141.

- ^ Anderson, Keith (1 April 2001). "Bantock: Hebridean Symphony / Old English Suite (Adrian Leaper/ Peter Breiner/ Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra)". Naxos Direct. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Byline, Joe Riley (17 May 2013). "Strauss, Brahms, Elgar Philharmonic Hall; Review". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "New Brighton Tower". Liverpool Mercury. 16 June 1900. p. 8. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Everett, Walter (2001). The Beatles As Musicians: The Quarry Men Through Rubber Soul. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 0195141059.

- ^ Norman, Philip (2009). John Lennon: The Life. HarperCollins UK. p. 246. ISBN 978-0007344086.

- ^ Murphy, Liam (21 November 2011). "Plaque unveiled to mark The Beatles connection with New Brighton Tower Ballroom". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "Mersey Map" (PDF). Visit Wirral. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ a b Pearson 1991, p. 76.

- ^ "At New Brighton Tower". Liverpool Echo. 14 July 1916. p. 5. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Hackenschmidt vs McInnery". Manchester Evening News. 1 June 1903. p. 6. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "The Season at New Brighton Tower". Aberdeen Evening Express. 20 May 1899. p. 3. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Pretty as a Postcard; Merseyside Tales". Liverpool Echo. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Baker, Anne (2010). Carousel of Secrets. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0755382439.

- ^ Franks-Buckley, Tony. "Books". Wirral History. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "An Acrobats Terrible Accident". Auckland Star. 17 June 1899. p. 5. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Dutton, Roy (2017). History of New Brighton Tower & Grounds. Infodial Ltd. UK. ISBN 978-0-9928265-4-3.

- ^ a b c d "Beautiful Victorian Game; with This Season Still Young, a Football Historian Recalls the Brief Reign of New Brighton Tower FC, Who Found You Can't Always Buy Success. David Charters Reports". Daily Post. 18 August 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "New Brighton Tower". Historical Kits. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Football: New Brighton Tower Dissolve". Lincolnshire Echo. 2 September 1901. p. 4. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "World's Cycling Championships 1922". British Pathe. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "New Brighton: The Tower Ground: 1933–1935". The National Speedway Museum. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "Motor Cyclist Dashes into crowd while competing in Team Race: Spectators Sustain Serious Injuries". The Courier. Dundee. 11 September 1911. p. 5. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Five Hurt in "Wall of Death" Booth". The Times. 19 May 1959. p. 6. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "New Brighton Tower". Liverpool Mercury. 14 August 1900. p. 1. Retrieved 3 July 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Whitsun". Exeter and Plymouth Gazette. 10 June 1924. p. 8. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Landmark Kent power station chimney blown up in demolition of UK's tallest concrete structure". MSN News. 7 September 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ "Wallasey Theatres". History of Wallasey. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Tower would attract tourists". Wirral Globe. Cheshire, Greater Manchester, and Merseyside Counties Publications (England). 21 August 1997. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

Bibliography

edit- Dutton, Roy (2017). The History of New Brighton Tower & Grounds. Infodial Ltd. England. ISBN 978-0-9928265-4-3.

- Easdown, Martin (2009). Lancashire's Seaside Piers. Wharncliffe Books England. ISBN 978-1-84563-093-5.

- Kennedy, Michael (1960). The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music. Manchester University Press.

- Morley, Thomas (2012). The Haunting. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4678-9656-6.

- Pearson, Lynn (1991). The People's Palaces: The Story of the Seaside Pleasure Buildings of 1870–1914. Art and Architecture Series. Barracuda. ISBN 978-0-86023-455-5.

- Roberts, Les (2012). Film, Mobility and Urban Space: A Cinematic Geography of Liverpool. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1846317576.

- Twydell, Dave (1995). Rejected F.C. Volume 3. ISBN 978-1-874427-26-1.

- Wheeler, Scott (2005). Charlie Lennon: Uncle to a Beatle. Outskirts Press. ISBN 1598000098.

External links

edit- New Brighton History Site: New Brighton Tower

- Little Richard & The Beatles at New Brighton Tower, October 1962

- History of Wallasey

- New Brighton Tower at Structurae