Motti Ashkenazi (Hebrew: מוטי אשכנזי; born 1940) is a Captain in the Israel Defense Forces reserves, who commanded the Budapest Outpost, the northernmost outpost of the Bar Lev Line during the Yom Kippur War. It was the only outpost that did not fall to the Egyptians. After the war, Ashkenazi led the protests against the Israeli leadership.

Captain Motti Ashkenazi | |

|---|---|

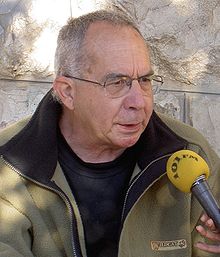

Motti Ashkenazi in 2007 | |

| Native name | Hebrew: מוטי אשכנזי |

| Born | 1940 (age 83–84) Haifa, Mandatory Palestine |

| Allegiance | Israel |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1958–1974 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Commands | Budapest Outpost (Bar Lev Line) |

| Battles / wars | |

| Other work | Political activism, public protests, author, strategic consultant |

Biography

editAshkenazi was born in Haifa, studied at the Kadoorie Agricultural High School, and was a member of the Machanot HaOlim youth movement. In 1958, he joined the IDF as part of a Nahal unit, volunteered for the Paratroopers Brigade, and served in the Paratroopers Nahal Battalion. In the Paratroopers, Ashkenazi completed training as a fighter, infantry squad commander course, and infantry officer course. Upon completion, he returned to the Paratroopers as a platoon commander in the Nahal Battalion and was discharged with the rank of Lieutenant.[1] During the Six-Day War, he served in the 68th Battalion of the Jerusalem Brigade and participated in the battles to liberate Jerusalem.

Entry into Political Activity

editShortly after the Six-Day War, Ashkenazi became actively involved in establishing the Movement for Peace and Security, which advocated for the establishment of an independent Palestinian entity alongside Israel. In the run-up to the 1969 Knesset elections, some voices in the movement called for transforming it into a political party. Ashkenazi, who strongly opposed this, left the movement. The new party did not pass the electoral threshold and thus ended its activity. In the early 1970s, Ashkenazi and other students assisted a group of young people from the Musrara neighborhood in Jerusalem in their fight for equality. This group later became known as the "Black Panthers". When the focus shifted to animosity against Ashkenazim, Ashkenazi warned that it was doomed to fail and withdrew.

Between 1972 and 1973, before the Yom Kippur War, Ashkenazi published a series of articles warning of an impending war due to the development of Egypt's "stages war doctrine", which later drove Anwar Sadat's limited strategic goals in the war. One such article, which pointed out the implications of this strategic policy and warned of the danger of ignoring it, was rejected by Gershon Rivlin, editor of the Defense Ministry's quarterly journal Maarachot, on the grounds that it was not suitable for the magazine. Frustrated by his inability to influence Israeli public opinion, Ashkenazi decided to approach senior military officers directly. He initially contacted the commander of the northern brigade along the Suez Canal, but when he felt unheard, he turned to his direct commanders in the 68th Reserve Battalion. According to Ashkenazi, these attempts failed.[2]

Yom Kippur War

editIn September 1973, two days before Rosh Hashanah 5734, Ashkenazi was called up for reserve duty. He arrived at the Budapest outpost, which was in a state of neglect following the end of the War of Attrition. From the moment Ashkenazi took command until the Egyptian attack began, he repeatedly warned his superiors about the poor condition of the outpost and the buildup of Egyptian forces, but his concerns were met with indifference. Despite this, Ashkenazi managed to improve the defenses of the outpost with the limited resources available to him. During the first six days of the war, Ashkenazi fought alongside his soldiers with the assistance of two tanks (from Battalion 9). Despite being cut off early on, Budapest, the only outpost of the Bar Lev Line under his command, withstood heavy shelling until the sixth day of the war, when it was relieved by soldiers from the Nahal's 906th Battalion. The outpost remained in Israeli hands until the ceasefire.[1]

Protest Movement

editAfter being released from reserve duty in February 1974, Ashkenazi became known for his public protests, calling for the resignation of Defense Minister Moshe Dayan.[3] He launched a 48-hour hunger strike and began protesting outside the Prime Minister's Office.[4] His solo protest quickly gained momentum, with tens of thousands of citizens and reservists joining him, calling for the government's resignation.[5] By the demonstration on March 24, 1974, 6,000 people participated.[6]

The protest coincided with the hearings of the Agranat Commission, which determined that senior military officials were responsible for the failures leading up to the war but exonerated the political leadership. Despite the results of the December 31, 1973, elections to the Eighth Knesset, which maintained the status quo in the government, Ashkenazi continued his protests against Dayan. During his hunger strike, Ashkenazi was invited to meet with Dayan through the mediation of Professor Nathan Rotenstreich.[7] Dayan claimed that the election results proved Ashkenazi wrong. However, in May 1974, just two months after forming her new government, Prime Minister Golda Meir resigned, signaling the eventual success of Ashkenazi's protest. Even after the resignation of Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan, Ashkenazi continued to demonstrate in June 1974.[8]

In November 1975, Ashkenazi petitioned the Israeli Supreme Court (Bagatz) to compel the Defense Minister and the IDF Chief of Staff to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the war's shortcomings and act on the Agranat Commission's recommendations to expose all failures and deficiencies.[9] His petition was rejected.[10]

Later career

editFollowing his protests, Ashkenazi was dismissed from his role as a company commander and was not called up for reserve duty for 11 years.[11] Over the years, he remained active in public protests, established a factory, developed and produced games, and occasionally worked as a strategic consultant for various organizations.[12]

In the early 1980s, Ashkenazi led protests against Prime Minister Menachem Begin and the autonomy plan that Begin was promoting at the time,[13] for which he received a death threat.[14]

In 1982, he petitioned the Supreme Court to require the government to finance kindergarten for self-employed working mothers.[15]

In January 1989, Ashkenazi led protests against high interest rates in Israel.[16]

In 1990, Ashkenazi was involved in a protest movement to change the political system in Israel, alongside Avi Kadish, Elias Shraga, and others.[17] This protest contributed to the enactment of the Direct Election of the Prime Minister law in 1992.[18]

Following the Second Intifada, Ashkenazi promoted a version of the confederation plan as a solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[19]

In 2002, ahead of the 2003 Knesset elections, Ashkenazi co-founded the party "Lehava – For Equality of Opportunity in Israeli Society".[20] The party received only 1,181 votes.

In 2003, Ashkenazi published a book recounting his experiences during the Yom Kippur War titled "This Evening at Six, War Will Break Out".[21]

In August 2006, Ashkenazi joined protest movements demonstrating in Jerusalem after the Second Lebanon War.[22]

In August 2011, he was one of the speakers at the 2011 Israeli social justice protests held at Kikar HaMedina.

Since 2017, Ashkenazi has participated in the protests against the Attorney General.[23] In January 2018, he spoke at a protest organized by the movement at Habima Square in Tel Aviv.[24]

In 2019, Ashkenazi ran for the 21st Knesset as part of the Social Justice Party.[25]

Further reading

edit- Motti Ashkenazi with Baruch Nevo and Nurit Ashkenazi, "This Evening at Six, War Will Break Out", Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 2003.

- Eitan Haber and Ze'ev Schiff, "Lexicon of the Yom Kippur War", Devir Publishing Zmora-Bitan, 2003, p. 64.

- Moshe Levana, "Our Israel, The Protest Movement After the Yom Kippur War, The Story of the Lost Generation's Protest", Effi Meltzer Ltd., 2019.

References

edit- ^ a b Eitan Haber and Ze'ev Schiff, "Lexicon of the Yom Kippur War", Dvir Publishing Zmora-Bitan, 2003, p. 64.

- ^ Motti Ashkenazi, "The Strategy and Tactics of the 'War of Stages'," Maariv, December 6, 1974, p. 18.

- ^ B. Amikam, "Demonstration today with Motti Ashkenazi: 'Enough of Dayan'," Al HaMishmar, February 17, 1974, p. 4.

- ^ "Motti Ashkenazi on hunger strike," Al HaMishmar, February 11, 1974, p. 13.

- ^ "Captain (res.) Motti Ashkenazi renewed his hunger strike in Jerusalem," Davar, February 11, 1974, p. 54.

- ^ Tuvia Mendelsohn, "6,000 people join Motti Ashkenazi's demonstration in Jerusalem," Davar, March 25, 1974, p. 4.

- ^ Haggai Ashdod, "Dayan met with Motti Ashkenazi," Davar, February 15, 1974, p. 3.

- ^ "Motti Ashkenazi resumes his hunger strike," Al HaMishmar, June 2, 1974, p. 86; B. Amikam, "Motti Ashkenazi renewed his individual protest, calling for elections no later than October 6," Al HaMishmar, June 3, 1974, p. 26.

- ^ "Motti Ashkenazi turns to Bagatz against the Defense Minister and Chief of Staff," Maariv, November 14, 1975, p. 36.

- ^ "Bagatz rejected Motti Ashkenazi’s petition," Davar, June 15, 1976, p. 42.

- ^ Yosef Walter, "It's quite humiliating," Maariv, November 4, 1986, p. 77.

- ^ Yael Paz-Melamed, "The Ashkenazi Revolution," Maariv, October 10, 1986, p. 284.

- ^ "Ashkenazi, Baum, and Livne will protest again today," Maariv, March 30, 1980, p. 127; Zvi Singer, "20 people came to demonstrate with Motti Ashkenazi," Maariv, March 31, 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Zvi Singer, "Death threat against Motti Ashkenazi," Maariv, April 13, 1980, p. 34.

- ^ "Self-employed mothers will also receive participation in kindergarten tuition," Davar, December 22, 1982, p. 45.

- ^ Ronit Antler, "The plow symbolizes the state of the means of production in the country. It's a tool that has gone out of operation" all because of Bruno," Hadashot, January 17, 1989, p. 34.1; "Motti Ashkenazi: War against interest rates," Maariv, January 17, 1989, p. 30.

- ^ "Agudat Yisrael and supporters of changing the system petition Bagatz against the agreements with Gur and Mizrahi," Hadashot, June 15, 1990, p. 13; Yaakov Rotblit, "New publication coming soon," Hadashot, May 21, 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Yair Tzoler, "The fight started here," Hadashot, January 7, 1992, p. 97.

- ^ Smadar Shmueli, "Exclusive: Motti Ashkenazi runs for the Knesset," ynet, July 15, 2002.

- ^ Tzvi Lavi, "29 lists submitted their candidacy for the 16th Knesset elections, including Center and Gesher," Globes, December 13, 2002.

- ^ Uri Bar-Joseph, "The personal account of a national optional war," Haaretz, November 24, 2003; Oded Naaman, "Steam: 2003, 1974, 1949," Haaretz, November 12, 2003.

- ^ David Shalit, "The Iron Curtain," Globes, August 22, 2006.

- ^ Dror Foer, "The protest demanding the investigation of Netanyahu has entered its 31st week," Globes, July 8, 2017.

- ^ "Corrupt politicians out: Thousands protest against corruption in Tel Aviv," Globes, January 6, 2018.

- ^ Shahar Hai, "Yom Kippur War protest leader runs for Knesset: 'To correct years of injustice'," ynet, January 13, 2019.

External links

edit- Ashkenazi, Motti. "30 years to the Yom Kippur War:Just a scared soldier". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.