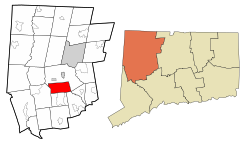

Morris is a town in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 2,256 at the 2020 census.[1] The town is part of the Northwest Hills Planning Region.

Morris, Connecticut | |

|---|---|

| Town of Morris | |

Morris Community Hall | |

| Coordinates: 41°41′38″N 73°12′38″W / 41.69389°N 73.21056°W | |

| Country | |

| U.S. state | |

| County | Litchfield |

| Region | Northwest Hills |

| Settled 1723 | Incorporated 1859 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Selectman-town meeting |

| • First selectman | Tom Weik (R) |

| • Selectman | Erica Dorsett-Mathews (R) |

| • Selectman | Vincent Aiello (D) |

| Area | |

• Total | 18.7 sq mi (48.5 km2) |

| • Land | 17.3 sq mi (44.9 km2) |

| • Water | 1.4 sq mi (3.6 km2) |

| Elevation | 994 ft (303 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 2,256 |

| • Density | 120/sq mi (47/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 06763 |

| Area code(s) | 860/959 |

| FIPS code | 09-49460 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0213465 |

| Website | www |

Europeans first began to settle the area that became Morris circa 1723. Originally part of the town of Litchfield, it was called the South Farms because of its location 5 miles (8 km) south of the center. Designated a separate Congregational parish in 1767 and incorporated as a town in 1859, it was named after native son James Morris, a Yale graduate, Revolutionary War officer, and founder of one of the first co-educational secondary schools in the nation.

Morris lies in rolling hill country of woods, wetlands, fields and ponds. It also encompasses much of Bantam Lake, originally called the Great Pond, which covers approximately 947 acres (383 ha) and is the largest natural lake in the state. The traditional Town of Morris seal features the pine on Lone Tree Hill, which overlooks the lake. Morris is home to one of the oldest state parks in Connecticut, as well as to one of the newest.

The area's transition from 18th-century settlement to semi-rural community in the 2000s is the story of many Connecticut towns and much of New England. At first, farming barely made families self-sufficient, but in the 1800s, agriculture evolved into a business. Then, over the next 150 years, competition, rising costs and increasing regulation made it less sustainable, despite economies and innovation. In the early 1900s, local water mills, manufactories and other small businesses encountered similar challenges and gave way to industry in nearby Waterbury, Torrington and beyond.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the area was still largely rural, but residents' occupations had grown more diverse. Today, the farming tradition continues even as residents engage in a range of professions, businesses and arts locally and in the wider region. A number of second home owners come from the metro New York area. In addition to the two state parks and Bantam Lake, the 4,000-acre (1,600 ha) White Memorial Conservation Center offers a range of opportunities for outdoor sports and recreation. Camp Washington is a spiritual retreat operated by the Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut.

Morris center looks like a typical small New England village, with a white Congregational church, a school, and town hall. Interspersed with fields and woods, a mix of Early American and newer homes strings out loosely along the town's roads. Children attend the local James Morris elementary school and regional Wamogo High School, a U.S. Department of Education school of excellence. Perhaps counter-intuitively, Morris also holds a Buddhist temple, as well as a Jewish cemetery from the early 1900s.

History

editPre-European

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

The Morris/Litchfield region lay in the borderlands between Mahican territory to the north and west and Paugussett land to the south and southeast. Both peoples were part of an Algonquian language population that extended up the coast in a wide swath from Virginia to Canada. Those in the immediate area, the Potatuck, were a Paugussett subgroup.[2]

The Potatuck were woodland dwellers whose bark wigwam and longhouse villages typically housed anywhere from 50 to 200 individuals. Their social structure was relatively simple and egalitarian. Kin groups were matrilineal, and women held authority over land rights and transfer.

Potatuck women gathered wild plants and fruits and raised the "Three Sisters" crops of squash, beans, and maize (corn), though there is some evidence that they began to cultivate maize only in the decades just before English settlers came to New England. Men fished and hunted deer and small game, also growing tobacco for ritual use. The Potatuck used fire as a tool for clearing underbrush to facilitate both hunting and planting. Some may have moved to the shore of Long Island Sound to fish and gather shellfish during the summer.

Like other first peoples in the northeast, the Potatuck believed in a Creator. His lodge, which lay to the west, was where worthy men and women went after they died. Individuals had spiritual guardians. These could be inanimate objects or ghosts but most often were animals. Festivals and other rituals taught that humans are part of nature — neighbors with plants and animals, which also possess spirits. Given their interdependence with the rest of creation, people were taught to respect and seek harmony in their physical and social environments and between earthly and spiritual worlds.

The Potatuck and the Paugussett, more generally, were part of a northeastern trade network whose water routes very probably extended to the midwest and possibly as far as the mid-south. Relations with neighboring groups were by and large harmonious. In the century before Europeans arrived in what became Connecticut, some of the Munsee people, a subgroup of the Lenape (who the English later called the Delaware), moved up the Atlantic coast. They appear to have coexisted and even intermingled with the Paugussett, whose pottery reflects the influence of their culture.

The Paugussett did not side with more easterly tribes such as the Narragansett and the Wampanoag in King Philip's War (1675–1678), which devastated the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Providence Plantation and Rhode Island. The Potatuck in northwest Connecticut had even less incentive than other Paugussett groups to become embroiled in the war because European presence in their territory was so limited—and would be for almost another half century.

European settlement

editEuropeans began to settle the region in 1715 after John Marsh came from Hartford to what was known as the Greenwoods, the thickly forested part of the colony that corresponded roughly to today's Litchfield County.[2] Having explored and found friendly inhabitants, Marsh and a partner, John Buell of Lebanon, Connecticut, petitioned the General Assembly for the right to establish a town at "a place called Bantam"—the name possibly a corruption of the Algonquian word Peantum, the Potatuck group who lived in the area.

Representatives from Hartford and Windsor negotiated with the Potatuck for land, creating the town of Litchfield, which included the area later known as the South Farms, in 1720. The Potatuck reserved rights to a hunting lodge near today's Mount Tom and Mt. Tom Pond, both of which became part of a 231-acre (93 ha) state park on the northwest side of Morris in 1915. While some natives welcomed, or at least tolerated, the newcomers, others did not. The region was subject to periodic Mohawk incursions from the north and west. Some years later, Zebulon Gibbs recalled a 1722 raid in which a settler was killed and scalped. "I was the first who found him dead," Gibbs said.[3]: 3

When colonists first lived in South Farms is unclear. Land deeds on the east side date to 1723, when local surveyors laid out the area's first east–west road.[4]: 1 Also on the east end, and perhaps even earlier, a north–south road from Litchfield's Chestnut Hill ran down through the section that became known as The Pitch (so-called because the settlers "pitched", or drew lots, for land there).[3]: 10 In 1724, the Connecticut Colony required settlers to build a fort, a log bulwark, on a hillside near the intersection of the old Woodbury (now Higbie) Road and present-day Benton Road. The work took them away from planting, diminished the year's harvest, and was consequently unpopular. The structure fell fairly rapidly into disrepair.[4]: 3

Colonial government policies and military action reduced the likelihood of conflict with native groups by 1726, when two European families lived near today's Litchfield-Morris border on a north–south track (now Alain White Road) that was more central to the area.[3]: 6 At least thirty families very probably lived in South Farms by 1747, since it had a school, which the General Assembly required of places with that number.[3]: 3 Meanwhile, colonial policies and disease had decimated the Potatuck. Some who remained merged with other nearby bands to form the Schaghticoke tribe, which still exists in Kent today. Individuals lived alongside the settlers through the 1700s and on into the 1900s. Typically, they adopted non-native customs and religion, though some also conserved elements of traditional culture such as the craft of basketweaving.

From settlement to town

editBetween 1747 and 1859, residents of South Farms were involved in sporadic arguments with the town of Litchfield, the colony, and after independence, the state, over control of their religious and civic activities.

Church and state were inextricably interconnected in the Connecticut Colony's early days. South Farms residents had to petition the General Assembly in Hartford for permission to build a meeting house, which would make it possible to avoid the long trip to the center of Litchfield in the winter. After years of resistance, the Assembly finally acquiesced in 1767, when it authorized the organization of a separate Ecclesiastical Society of South Farms.[3]: 5 Instead of ending the friction over local control, this act presaged ongoing arguments about the fair division of payments for the existing Litchfield church as well as about funding for the new meeting house in South Farms and for the four, then five, then six schools there.

During the Revolutionary War, South Farms residents were taxed heavily to support the rebellion, and over 100 men served in either the militia or the Colonial Army.[5] Some went to the defense of Danbury after British forces attacked a supply depot in 1777, others as far as Canada and Virginia.[3]: 6

Perhaps the most noteworthy was James Morris, who as a youth had been tutored by Bethlehem minister Joseph Bellamy, a significant figure in the religious Great Awakening. Morris considered a calling to the ministry after he graduated from Yale in 1775, but in 1776 he joined the Continental Army instead, fighting at Long Island and White Plains before being captured at the Battle of Germantown in Pennsylvania. He was imprisoned in Philadelphia, paroled on Long Island, and subsequently exchanged. In the last years of the war, he served as a captain of light infantry under Alexander Hamilton at the Battle of Yorktown.[6]: 14–15

After the war, Morris returned to South Farms, where he cared for his ailing parents. Concerned for the education and moral welfare of the community's youth, he began sharing his library with, and teaching, both boys and girls. Fearing that the girls would grow to be too independent, some locals tried to censure him. His alleged transgressions included permitting students to dance at the close of lessons, treating female students too familiarly, and allowing them to pursue an academic course of study in the first place. The controversy led to a public hearing in which Morris prevailed. In 1803, he opened an academy in a new school building.[6]: 28–34

The Morris Academy was one of the new nation's first coeducational secondary schools, "instructing youths…in the higher branches of literature and the sciences together with the Christian precepts of morality and virtue."[6]: 33 During the years in which it existed, students came from 63 Connecticut towns, 15 states and 10 countries including Argentina, France, Germany, Spain and the West Indies. Among them were the abolitionist John Brown; William and Henry Ward Beecher, brothers of Harriet Beecher Stowe; the native Hawaiian Henry Obookiah, who was a symbol of the American Foreign Mission movement, and Samuel Mills, its "father;" a governor and a lieutenant governor of Connecticut and four congressmen. Morris died in 1820, but the academy continued for another 68 years, having educated more than 1,200 young men and women by the time it closed.[6]: 81–90

By 1810, when families were still largely self-sufficient, South Farms farmers cultivated wheat, rye, corn and oats. Women spun flax for linen. Sheep and cattle produced wool and milk, respectively, while oxen provided power for field labor. Water mills turned out grist and lumber, as well as seed for products such as linseed oil. Scattered throughout the area were several small stores, smithies, cider mills and other small businesses.[3]: 13–14

Although its location was rural, South Farms in the early 1800s had connections to the outside world not only because of the academy's relatively diverse student body but also because it was part of an active transportation network. At the time, the area had two centers. One at the east end (now East Morris) was at a four corners on the Straitsville toll road (today Straits Turnpike/Route 63), which connected farther north to Litchfield, Albany and Vermont and which ran south to New Haven. Drovers used the roads to move horses, cattle and mules from as far as Vermont. Concord stages brought travelers to and through the area, where they stopped and stayed at local taverns.[3]: 14

Ultimately, however, the more westerly crossroads (leading to East Morris, Litchfield, Bethlehem, Washington and New Milford) became South Farms' hub. It was more geographically central. A public school; the Morris Academy; and the church, a focus of social life, were there. Also, odors from an East End tannery grew so noxious, people moved to be away from it.[7] South Farms had a Society for Moral and Intellectual Improvement as well as a Lyceum for debating contemporary issues. It also had the first library in Litchfield, dating to 1785.[3]: 14

By 1829, the Great Pond was called Bantam Lake, and local entrepreneurs advertised pleasure cruises and "a small establishment" where ladies and gentlemen could "spend a few hours on and about this beautiful sheet of water."[3]: 14

In 1786 and again in 1810, the South Farms Society had sought Litchfield's permission to form a separate town because of concerns about autonomy similar to those that had prompted the earlier petition for a separate parish. Litchfield successfully opposed both in the General Assembly. In 1859, however, the Assembly approved the voters' petition for separation. In it, they had described the problems caused by their distance from Litchfield, its inattention to their concerns, and the cost of maintaining roads and bridges that were far removed from them.[8] The new town was named after its native son, the Revolutionary War soldier and pioneering educator.

A farming community

editAt its creation, Morris was a farming community of 10,400 acres (4,200 ha) and about 700 souls. "Almost every homestead was a farm to some degree, …much the same … agricultural economy" as a century before.[3]: 103

Two years later, young men from Morris were serving in the Union Army, mostly in the 19th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry—later the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery Regiment—organized in Litchfield. By the end of the Civil War, at least 33 Morris men had fought in some of the bloodiest battles of the conflict, from Cold Harbor to Atlanta to Petersburg. Five had died. Resident Mary Stockbridge said that when "one after another of the flower of our town was laid in our yard, our hearts were nearly broken."[3]: 142

In a town where the majority of voters were Democrats, a number questioned the war. Supporters of the Union cause argued vigorously, and sometimes heatedly, with these "white feather" peace advocates. A tradition of lively public exchange continued through the conflict and after; at its conclusion, the Lyceum debated whether representatives from the late Confederacy should be seated in Congress.[9]

At the start, agriculture had made New England families self-sufficient. In the 1800s, it became a profit-making enterprise, especially as the railroad opened markets farther from home. Over the course of the 19th century and into the 20th, farming also became a race to offset narrowing profit margins by expanding sales and creating economies. A major part of the problem was the so-called "tragedy of the commons:" what made sense for a single commercial farmer—producing more goods for sale—was not in either his or the common interest when everyone did the same. More production meant more supply for a limited market. More supply from local farms and still more from beyond the region depressed prices. Profitability suffered.

Farmers in Morris adapted with Yankee ingenuity. Over time, they lowered overhead by reducing the number of workers they needed; they employed new technologies—substituted mechanical reapers and mowers for scythe and cradle, for instance. With better machinery, they could retire their oxen and use horses for work—animals that then doubled as transportation. Later, in the 1900s, trucks and tractors replaced horses. Other innovations—electrical milking machines, refrigeration for milk, for instance—continued to improve efficiency and productivity.

They also planted new crops—potatoes, sweet corn and cabbage—to appeal to new markets in Waterbury and elsewhere. For a time, the newly built Shepaug Railroad took milk from West Morris to New York City, but dealers there collaborated to lower the prices they paid the farmers and to increase their own profits. The farmers responded with a cooperative that sold and delivered their milk, but they were still competing with other producers from other areas. In 1892, they voted to accept a half cent a quart less than twenty years earlier.[3]: 107

They invented new organizations and adopted new practices. In 1934, they created the Dairy Herd Improvement Association. In 1936, the federal Agricultural Adjustment Act began providing assistance to farms. In 1940, Albert Humphrey produced the first test tube calf in Litchfield County.[3]: 110 But even as they created economies and innovated, costs rose. New regulations like tuberculin testing and vaccination for cows proved burdensome. Machinery and equipment—large milk holding tanks, for instance—were increasingly expensive.

By the late 1950s, therefore, the size and productivity of Morris' working farms had grown, but their number had declined. To add to their problems, improving transportation systems and refrigeration had made product from the fertile Midwest—and beyond—ever more cost-competitive. By the 1970s and 1980s, therefore, agriculture in Morris was becoming what it was in the 2000s—a couple of larger operations, underwritten by income from other sources, and smaller ones that served specialty markets. It had become harder and harder, if it wasn't impossible, to make a living by farming alone.

The rise and decline of industry

editThe other main economic driver in 19th- and early 20th-century Morris was its collection of water mills, general stores, and other small businesses, some of which had begun as home industries.

One of the more interesting, if somewhat anomalous, businesses during this period was a copper mine on east end land purchased by P.T. Barnum in 1850. Located on 46 acres (19 ha) near Saw Mill Brook (later dammed to create the Pitch Reservoir), it had two vertical shafts and a tunnel and was a financial bust.[10]

By the late 1800s, the town had three saw or grain mills and a wood-turning mill. Shops produced items from clothes frames to the scythe sharpeners known as "Emmons rifles" to innovative horse-drawn hay rakes, to wagons and sleighs. Some operated in manufactories, others in barns or other farm buildings. The town also had a brickyard; tanneries; cattle dealers; and smithies where workers shoed animals, produced knives and made other implements.[3]: 112–120

Mass production and new technologies threatened these small businesses in much the same way rising costs and external competition had affected agriculture. Through the late 1800s and early 1900s, manufacturing shifted to larger towns and cities like Waterbury, which flourished well into the 20th century. Furthermore, from the Great Depression and two World Wars, in which over 75 Morris residents served and two died, emerged a national economy, accelerated urbanization and a more mobile population.

The modern era, a case study in transition

editBy the late 1950s and early 1960s, therefore, Morris and similar towns were in transition. The remaining farms were surrounded by large tracts of open land, field and forest where stone walls were reminders of former pastures. Small businesses had changed with the times—the town now had gas stations instead of a wagon manufactory, for instance—but these operations, too, had to reckon with outside competition, and some would close. A growing number of residents commuted to nearby towns and cities for work.

Twenty years later, some farmland had been broken up and developed; for the most part, however, housing was still a mix of Early American structures and newer ones strung loosely along or back from a handful of main roads. Telephones, television, radio, and the roads connected Morris to the rest of the world. Second-home owners from metro New York added to its diversity. But in some ways, the town was not so different from what it had been in the 1800s.

Although it was only two hours by car from New York City, its relative isolation protected it from heedless development and urban sprawl. On the other hand, its location posed special challenges. How would it stay economically viable when local farms and businesses faced low-cost competition from elsewhere? How would it hold onto a population with a healthy mix of ages and incomes when outside opportunities beckoned?

To meet these two challenges, it would have to contend with a third: How would it support desirable development and simultaneously protect the low-key rural character and natural beauty that attracted people in the first place?

Connecticut authorized regional development planning in 1947, and in 1969 it required localities to create their own plans for conservation and development.[11] Meanwhile, normal property turnover and individual initiative shaped development less intentionally. Several outcomes were noteworthy.

Developments and trends

editDemographics

editBetween 1950 and 2010, the population of Morris roughly tripled, from 770 to 2388.[12] At the same time, it was aging. By 2017, the median age in the U.S. was 38, in Connecticut 41, and in Morris 47, which was actually lower than in many other area communities.[13] These developments reflected the town's transition from a primarily agrarian to a semi-rural community with mixed employment. There were more second homes, often owned by weekenders from the metropolitan New York area.

Also, high school graduates from Morris—as well as from other Litchfield County towns, generally—were more likely to leave after completing their formal education, both as a result of normal mobility and because of limited job prospects. Nonetheless, a number remained or came back to the region. In Morris, three quarters of residents were Connecticut natives.[12]

There were 29 towns in Litchfield County. Median income in Morris was eighth highest. Birthrate and family size were the state average.[13]

Agriculture

editBy the early 2000s, there were at least three different models of agriculture in Morris:

- Marketing a specialty product nationally while also supporting traditional product. White Flower Farm,[14] founded in 1950, raised flowers and shrubs for national distribution and had beef cattle as a sideline.

- Marketing traditional products regionally, with support from other activities. South Farms,[15] named for the original settlement, was a several-generation enterprise that had reinvented itself as an event venue. It also leased property for raising hops. The income supported cultivation of corn and cattle.

- Targeted regional marketing of traditional product. Truelove Farm,[16] a smaller operation, marketed beef, ham and produce to targeted sources.

Although the locally-grown movement and specialty markets (hops, e.g.) had created new opportunities, farmers were still squeezed by the availability of cheap goods from outside the area; by the dis-economy of running small or mid-sized operations as equipment, technology, insurance and other costs rose; and by the cost of state health and other regulations, which often failed to reflect the realities of small non-dairy farming.

How a more robust farm economy could develop under these conditions was unclear.

Tourism, recreation, spiritual renewal

editBantam Lake had attracted visitors since at least the 1820s, and by late in the nineteenth century, its southern third had become a summer destination for cottage renters and hotel guests. On the east end of town, meanwhile, investors had purchased a large amount of land, where they planned to build a new hotel and spa, a version of Saratoga, but closer to New York City.

The dream of South Farms Springs died in 1904, a story of liens, attachments and lost possibility.[17] Meanwhile, life by the lake flourished. Restaurants and a dance and roller-skating pavilion appeared in the early 1900s. Though these commercial enterprises had closed by the 1990s, the lake remained an attraction for visitors, summer residents and, increasingly, year-round homeowners.

South Farms Springs' spiritual successor was the 113-acre (46 ha) Winvian Farm, whose owner in the 1940s was Winthrop Smith, a partner of Merrill, Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Smith. After his death in 1961, his widow, Vivian, married Charles McVay, former captain of the doomed World War II heavy cruiser Indianapolis. In 2009, Smith's daughter-in-law turned Winvian into a luxury hotel that included the 1775 Seth Bird house and 18, sometimes exotic, theme-based cottages—a tree house and one built around a helicopter, for example—as well as a spa, a pool, and a five-star restaurant.

In 1999, the Woodbury-Southbury Rod and Gun Club purchased the 238-acre (96 ha) Anderson Farm on Higbie Road, which the same family had operated for several generations. The property remained in farmland and served simultaneously as a fishing and bird hunting preserve.

Mount Tom and Mount Tom Pond were parts of Mount Tom State Park, Connecticut's oldest. Camp Columbia became its newest in 2000. The 590-acre (240 ha) tract included a small slice of land on Bantam Lake, a much larger expanse of field and forest with hiking trails to its south, and a section of wood and wetland to the west, across Route 209. Originally four adjoining farms, it was purchased by Columbia University in 1903 for a school of engineering field station. It was also a training camp for army officers during World War I and later a summer camp for the Columbia football team.

The White Memorial Foundation, created in 1913 by Litchfield residents Alain White and his sister, May White, to honor their parents, acquired 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of former farmland, about half of it in Morris. The northern and eastern parts of Bantam Lake shoreline were Conservancy property, along with 40 miles (64 km) of trails, an education center, a museum and research stations. The Conservancy's mix of fields, forest, ponds and wetland, as well as the lake and Bantam River, was open to the public for a range of outdoor activities that included hiking, horseback riding, kayaking and cross-country skiing.

The Mattatuck Trail, a 42.2-mile-long (67.9 km) intermediate hiking trail, ran through the White Conservancy, eastward across the northern edge of the town, and down a ridgeline in The Pitch on the way to Waterbury. Its name was an Algonquian term for the Waterbury area, meaning "place with no trees".[18]

Finally, the Rev. Floyd Kenyon had founded 300-acre (120 ha) Camp Washington in the Lakeside section of Morris in 1917. Originally a summer residential camp for boys, it later became co-educational. In 1991, its owner, the Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut, finished renovating and building facilities to create a year-round retreat and training center for all age groups, as well.

These resources helped to preserve the town's rural character. Like the prospects for farming, however, the potential for further development in tourism and recreation was unclear.

Open space

editOutside of the two state parks and the White Memorial Conservancy, Morris in the 1990s was still largely woodland, wetland, and farmland, some working and some former. Concerned about maintaining the town's scenic, rural character, a group of residents in 2006 created the not-for-profit Morris Land Trust,[19] where conservation easements would permanently limit non-farm development and protect agricultural resources.

The largest acquisition was the 2017 transfer of the 138-acre (56 ha) Farnham farm, which had been in the same family since 1735—an addition made possible by financial support from the Connecticut Farmland Trust. The property includes "farm fields, stone walls, meandering streams, wetlands, diverse forest habitat, and a portion of the Mattatuck Trail."[20] The land trust continued to seek additions of property consistent with a strategic plan that set priorities for land acquisition. Funding remained an ongoing challenge.

Serving as the water supply for the City of Waterbury, the Pitch Reservoir and most of the Morris Reservoir, as well as their wooded watersheds, had also been dedicated open space since the early 1900s. They connected to the Shepaug Reservoir in Warren through a 7-mile-long (11 km) tunnel, completed in 1926, that ran under Bantam Lake.

Education

editA well-educated populace was essential to the town's—and region's—civic health and economic well-being. Since at least the 1850s, the story of Morris's schools had been one of consolidation and extension—from several common schools to one elementary school; from three upper grades to local to regional high school.

At the time of its incorporation, Morris had six separate school districts, each with its one-room common school (ages 6–14) and single teacher. Though public high schools began to appear elsewhere in Connecticut during the 1850s, Morris families could pay tuition for their children to continue their education at the Morris Academy. Litchfield High School also became an option in mid- to late century, initially on a tuition basis.[3]: 56 The Morris Academy closed in 1888 following a long-term decline in enrollment. A significant factor was competition from publicly funded public schooling, which the state had mandated and begun to support financially twenty years before.

In 1904, 142 of 158 registered Morris voters approved a proposal to provide instruction for students up to the age of 17.[3]: 60 Older pupils were taught in the Congregational minister's home. Later they moved to the Center School, which was raised to include a room on the second floor; younger children continued in the one room on the first. Students who wanted a diploma could complete their final year of high school in Litchfield.

Until 1910, children in the common school had been taught a more-or-less single curriculum, with adaptation for individual differences. Thereafter, the teacher was supposed to differentiate instruction by grade level—a big challenge, given the range of ages and abilities in a single room. The new "upstairs" class of 22 older children faced the same challenge, according to a state inspector—though he noted that the "school is doing a great service to the community," preparing them for successful work at Litchfield High.[21]

In 1918, an inspector observed essentially the same conditions and said that "The difficulty for the teacher does not consist in the number of pupils, it lies … in the fact that there are so many different classes of work (subjects and levels) to teach." He added that "Morris is above the average in respect to the interest taken by the people in social life. During the year, the School… has done much in the line of entertainment which has tended to draw the people (of the town) together."[22]

In the first part of the 20th century, "(a)n unusually large percentage of the pupils in Morris attended high school. The showing…they made… was a matter of pride to the townspeople."[3]: 62 While some graduates remained in town, others made a difference in the wider world. Sally May Johnson studied at Simmons, graduated from the Massachusetts General Hospital School for Nurses and from Teachers College, Columbia, became Chief Nurse at the Army School of Nursing after serving in World War I, and later was an administrator at Mass. General.

Speaking to the American Nurses Association, she described her childhood in "a little rural New England village, where there were space, clean air, glorious sunsets, starry heavens at night, always a beautiful landscape—a place where fine people lived nobly and without ostentation."[23]

The state began to reimburse towns for elementary school transportation in 1931, after which the town voted to consolidate its six districts and house all students in one new building at the site of the old Center School. With large enough numbers together under a single roof, there could be a class at each grade and a single curriculum in each class. The James Morris School opened in 1932. In 1935, the Board of Education voted to extend the high school program to a full four years.[3]: 64–65

Rising enrollments created a need for more classroom space in the late 1940s. One option was to create a new, larger, secondary school by consolidating again, this time with one or more neighboring towns. After considering the idea's educational and financial advantages, the town united with Warren and Goshen in 1953 to form Regional School District 6.[24][3]: 66 Atypically, the new Wamogo High School was sited in none of the participating communities, but in centrally located Litchfield. Each town retained its own elementary school.

In the following years, and especially as enrollments began to tail off in the 1970s, there was periodic talk of yet more consolidation, this time with Litchfield. Outreach led nowhere on at least two occasions. By the 2000s, however, some grades at the elementary school had a single class and fewer than ten pupils. Meanwhile, Wamogo held roughly 520 students in grades 7–12, including a number from other districts in its award-winning grade 9–12 agri-science program.[25] Litchfield's grades 7–12 had approximately 530 students, a total of about 70 per grade.[25] As a result, consolidation was again a topic of conversation.

In June 2022, after nearly 70 years of episodic discussion and two years of study, voters in each town approved a plan to come together in a new regional District 20. The decision will create a new, merged high school on the Wamogo campus, and a new middle school at the former Litchfield High School. Each town will retain its local elementary school.

Following the creation of a new 12-person board of education and two years of planning, the merged secondary schools will open in the fall of 2024.

Among the reasons for the positive vote were the possibility of offering more courses and a wider array of athletic and other co-curricular opportunities, as well as projected financial savings. Opponents expressed concern that larger Litchfield might override the interests of the smaller towns.

Economic activity and employment

editBetween the new Region 20 school district and the several area independent schools, elementary and secondary education was a significant sector of employment in Morris in the first years of the 2000s. Recreational activities and tourism generated economic activity at Popey's Ice Cream Shoppe, at West Shore Seafood, in marine repair and dock installation, and at the handful of other stores in town, as well as in service businesses.

In addition to Winvian, White Flower Farm, and South Farms, other local businesses with broad regional or national reach included I2 Systems (LED lighting design and manufacture), Brierwood Nursery, BigTool Rack, and Harvest Moon timber-frame construction.

Other businesses, professions and entrepreneurial activities fell into no single category. A representative list included agriculture, antique furniture restoration, blacksmithing, construction, electronics, engineering, excavation, furniture design and construction, house painting, interior design, investment, law, lawn care, local and state government, marine products, media, metal fabrication, musical instrument production, nursing, nurseries, physical therapy, publications, horse farming and riding, software design, tree care, veterinary medicine, visual art, winery design and production.[26] Just under a quarter of workers were self-employed.[27]

Considering regional demographic and economic trends in the second decade of the 2000s, local committees and regional entities—the Northwest Connecticut Economic Development Corporation, the Northwest Hills Council of Governments, the Northwest Connecticut Chamber of Commerce, ConneCT and the Rural Lab—began to develop strategies for bringing enhanced fiber-optic communication to the entire region, as well as for promoting tourism, arts and culture, farming, manufacturing and innovation/entrepreneurship.

Geography

editMorris is in south-central Litchfield County, directly south of Litchfield, the former county seat, 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Waterbury, and 31 miles (50 km) west of Hartford, the state capital. According to the United States Census Bureau, the town of Morris has a total area of 18.7 square miles (48.5 km2), of which 17.3 square miles (44.9 km2) is land and 1.4 square miles (3.6 km2), or 7.33%, is water.[28]

Principal communities

edit- Lakeside

- Morris center

- West Morris

- East Morris

Government

editThe local government of Morris is run by three selectmen elected by the town at large. The First Selectman is the full-time chief executive and administrative officer responsible for the day-to-day operation of the town government. The Board of Selectmen establishes administrative and personnel policies and executes town policies and regulations.[29]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 769 | — | |

| 1870 | 701 | −8.8% | |

| 1880 | 627 | −10.6% | |

| 1890 | 584 | −6.9% | |

| 1900 | 535 | −8.4% | |

| 1910 | 681 | 27.3% | |

| 1920 | 499 | −26.7% | |

| 1930 | 481 | −3.6% | |

| 1940 | 606 | 26.0% | |

| 1950 | 799 | 31.8% | |

| 1960 | 1,190 | 48.9% | |

| 1970 | 1,609 | 35.2% | |

| 1980 | 1,899 | 18.0% | |

| 1990 | 2,039 | 7.4% | |

| 2000 | 2,301 | 12.8% | |

| 2010 | 2,388 | 3.8% | |

| 2020 | 2,256 | −5.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] | |||

As of the census[31] of 2000, there were 2,301 people, 912 households, and 640 families residing in the town. The population density was 133.9 inhabitants per square mile (51.7/km2). There were 1,181 housing units at an average density of 68.7 per square mile (26.5/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.48% White, 0.70% African American, 0.13% Native American, 0.83% Asian, 0.17% from other races, and 0.70% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 0.87% of the population.

There were 912 households, out of which 31.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 60.2% were married couples living together, 5.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.8% were non-families. 24.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.03.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.6% under the age of 18, 4.9% from 18 to 24, 28.4% from 25 to 44, 27.9% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.8 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $58,050, and the median income for a family was $63,293. Males had a median income of $49,063 versus $37,279 for females. The per capita income for the town was $29,233. About 3.4% of families and 6.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.8% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of October 25, 2005[32] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Republican | 653 | 8 | 661 | 40.01% | |

| Democratic | 339 | 2 | 341 | 20.64% | |

| Unaffiliated | 639 | 11 | 650 | 39.35% | |

| Minor Parties | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Total | 1,631 | 21 | 1,652 | 100% | |

Transportation

editMorris contains three main north–south roads and two main east–west roads:

- On the east end, Route 63 heads north from East Morris to Litchfield (a section also known as Litchfield Road) and goes south to Watertown (a section also known as Watertown Road.)

- From Morris center, in the middle of town, Route 61 heads north briefly before angling east on County Road and connecting with Route 63, headed to Litchfield. It goes south from the center, on South Street, to Bethlehem.

- Route 109 goes east from the center on East Street and passes through East Morris, where it intersects with Route 63 before continuing as Thomaston Road and ending in Thomaston. Heading west from Morris center on West Street, it goes through Lakeside and West Morris to Washington Depot.

- Running through the northwest corner of Morris, U.S. Route 202 goes northeast–southwest between Litchfield and New Milford.

- West of the center, in Lakeside, Bantam Lake Road/ Route 209 runs north–south between routes 109 and 202, along the western shore of Bantam Lake.

Notable locations

edit- Bantam Lake, largest natural lake in Connecticut, recreation site, home of oldest water ski club in America

- Camp Columbia State Park/State Forest, one of Connecticut's newest state parks

- Camp Washington,[33] coeducational summer camp, retreat center for the Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut

- Mattatuck Trail, medium difficulty hiking trail extending from Warren to Waterbury

- Mount Tom State Park, located in Morris, Litchfield and Washington. Mt. Tom summit (981 ft./ 299 m.) and tower are in Morris.

- South Farms, registered historic farm venue

- White Memorial Foundation, a 4,000-acre (1,600 ha) nature sanctuary, located in Morris and Litchfield

- Winvian, a luxury hotel and resort

Notable people

edit- Chuck Aleksinas (born 1959), drafted by the Chicago Bulls of the NBA, played for the Golden State Warriors; graduated from Wamogo High School, where he scored over 1000 points; played at Kentucky and finished college as a player at UConn

- P.T. Barnum (1810–1891), born in Bethel; showman, politician, and businessman; owned an unsuccessful copper mine in the Pitch area of East Morris

- John Brown (1800–1859), abolitionist who advocated armed insurrection to overthrow slavery; executed after forcibly occupying the armory at Harper's Ferry, VA; born in Torrington, student at Morris Academy

- Alexander Hamilton Holley (1804–1887), born in Salisbury, student at Morris Academy, President of Holley Manufacturing Company, 40th Governor of Connecticut

- Sally May Johnson (1880–1957), teacher; forerunner of women in the armed services; established and was Chief Nurse at the Army School of Nursing, Walter Reed Hospital, World War I; progressive Administrator of the Massachusetts General Hospital School of Nursing and Nursing Service

- Charles Lockwood (died 1886), farmhand; allegedly murdered a 16-year-old girl in July 1886 and hanged himself from a tree to avoid capture; widely speculated in the contemporary press that he was lynched by angry posses; possibly the only lynching in Connecticut or New England history

- Charles B. McVay III (1898–1968), Captain, U.S. Navy; Commander of the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis; court-martialed and posthumously exonerated after the vessel was torpedoed and sunk, having delivered atomic weapons to Tinian Island in the Pacific

- Samuel John Mills (1783–1818), congregational minister, missionary; as a Williams College undergraduate, a founder of the American Foreign Mission movement; Torrington native; student at Morris Academy

- James Morris (1752–1820), Yale graduate, officer in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812; educator and founder of one of the first coeducational schools in the nation; lived and died in South Farms, the part of Litchfield incorporated as a town in 1859 and named after him

- John Mason Peck (1789–1858), born in Litchfield, educated at Morris Academy; Baptist minister, Western frontier missionary, abolitionist; founder of first Baptist church in St. Louis, Shurtleff College (now part of Southern Illinois University)

- John Pierpont (1788–1866), Yale graduate, Litchfield Law School, Unitarian minister at Boston's Hollis St. Church, abolitionist, teacher, lawyer, legislator, poet; grandfather of John Pierpont Morgan

- Winthrop H. Smith (1893–1961), businessman, investment banker and name partner of Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith

- Frederick Whittlesey (1799–1851), New Preston native, educated at Morris Academy and Yale; professor at Genesee College (now Syracuse University); New York State Supreme Court judge and member of Congress

- George Catlin Woodruff (1805–1885), Litchfield native, educated at Morris Academy and Yale, Militia Colonel, General Assembly member, Congressman

References

edit- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Morris town, Litchfield County, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Carley, Rachel (2011) Litchfield: The Making of a New England Town, Litchfield Historical Society, p.19

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Weik, Laura Stoddard et al. (1959) One Hundred Years: History of Morris Connecticut, Morris Centennial Committee

- ^ a b France, Walter D. (Mar. 1998), The Development of East Street, South Farms (unpublished)

- ^ Schmidt, Eileen Porter ed. (2019) Litchfield Connecticut: Celebrating 300 Years 1719-2019, Greater Litchfield Preservation Trust, p.52

- ^ a b c d Strong, Barbara Nolen (1976) The Morris Academy: Pioneer in Coeducation, 1976, Morris Bicentennial Committee

- ^ France, Walter D. (Apr. 2000) Morris Historical Society Newsletter (unpublished)), p.1

- ^ Weik p. 16, quoting the Petition to the General Assembly (Feb. 1859)

- ^ Weik pp.34-35, quoting the Litchfield Enquirer (Aug. 1861) (1865)

- ^ France, Walter D. (1994) Map of the Copper Mine Site at South Farms (unpublished)

- ^ Connecticut General Statutes Title 8, CT General Statutes 8-23 (History), lawjusticia.com, retrieved September 9, 2019

- ^ a b Decennial Census (2010) Federal Bureau of the Census

- ^ a b Connecticut Demographics Data, towncharts.com, retrieved August 29, 2019

- ^ White Flower Farm

- ^ South Farms

- ^ Truelove Farm

- ^ South Farms Inn and Litchfield Springs Co. correspondence (1904) document 00/2013-129-0, litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org

- ^ Casper, Kenneth, connecticutexplorer.blogspot.com, 2014/02, "The Mattatuck Blue Blazed Trail", retrieved September 16, 2019

- ^ Morris Land Trust

- ^ "Morris Land Trust, CT Farmland Trust partner to protect historic farm" (August 11, 2017), The Register Citizen, registercitizen.com, Hearst Media Services, retrieved August 24, 2019

- ^ Weik, p.61, quoting the State Inspector's report (undated)

- ^ Weik, p.62, quoting the State Inspector's report (1918)

- ^ Weik, p.173, quoting Johnson, Sally May (Apr 11, 1929), "Reminiscences of a Connecticut Yankee, Healthwise and Otherwise", American Nurses Association Meeting, New England Division, New Haven, CT

- ^ Regional School District 6

- ^ a b Connecticut Report Cards, edsight.ct.gov, retrieved August 25, 2019

- ^ Businesses in Morris Connecticut, b2byellowpages.com, retrieved August 29, 2019

- ^ Northwest Hills Regional Profiles; townofwinchester.com, retrieved August 25, 2019

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Morris town, Litchfield County, Connecticut". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ "Town of Morris CT -". www.townofmorrisct.com. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of October 25, 2005" (PDF). Connecticut Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2006. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- ^ Camp Washington