The Moenkopi Formation is a geological formation that is spread across the U.S. states of New Mexico, northern Arizona, Nevada, southeastern California, eastern Utah and western Colorado. This unit is considered to be a group in Arizona. Part of the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range, this red sandstone was laid down in the Lower Triassic[1] and possibly part of the Middle Triassic, around 240 million years ago.[2]

| Moenkopi Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: | |

Moenkopi at its reference section along the Little Colorado River west of Cameron, Arizona | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Sub-units | See "Members" section |

| Underlies | Chinle Formation |

| Overlies | Kaibab Limestone |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone |

| Other | Shale |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 35°55′05″N 111°29′20″W / 35.918°N 111.489°W |

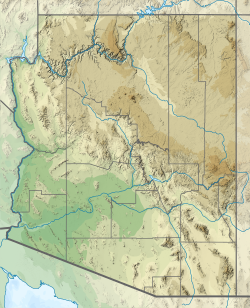

| Region | Northern Arizona Southeast California East-central Nevada Southern Utah Northwestern New Mexico Southwestern Colorado |

| Country | Southwestern United States |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Moenkopi Wash |

| Named by | Ward |

| Year defined | 1901 |

History of investigation

editThere is no designated type locality for this formation. It was named for a development at the mouth of Moencopie Wash in the Grand Canyon area by Ward in 1901.[3] In 1917 a 'substitute' type locality was located by Gregory in the wall of the Little Colorado Canyon, about 5 miles below Tanner Crossing in Coconino County, Arizona.[4] While in the Great Basin, Bassler and Reeside characterized and named the Rock Canyon Conglomerate, Virgin Limestone, and Shnabkaib Shale members in 1921.[5] Salt Creek (later replaced by Wupatki and Moqui Members) and the Holbrook Member were found and named in the Black Mesa basin by Hager in 1922.[6]

The Sinbad Limestone Member was named in the Paradox Basin by Gilluly and Reeside in 1928. Williams and Gregory named the Timpoweap Member in the Plateau sedimentary province in 1947.[7]

The Wupatki Member was first used in the Plateau Sedimentary Province and its age was modified to Early and Middle(?) Triassic by McKee in 1951.[8] Contacts were revised by Robeck in 1956 and Cooley in 1958. The Tenderfoot, Ali Baba, Sewemup, and Pariott Members were named in the Piceance and Uinta Basins by Shoemaker and Newman in 1959.[9] The Hoskinnini Member was assigned in the Black Mesa and Paradox basins by Stewart in 1959.[10] Contacts were revised again by Schell and Yochelson in 1966. Blakey named the Black Dragon, Torrey, and Moody Canyon members in the Paradox Basin and Plateau Sedimentary Province in 1974.[11] Contacts were revised yet again by Welsh and others in 1979.

Kietzke modified the age to Early and Middle Triassic using biostratigraphic dating in 1988. The Anton Chico Member was assigned in the Palo Duro Basin and areal limits set by Lucas and Hunt in 1989.[12] In 1991 areal limits were set again by Lucas and Hayden. An overview was completed by Lucas in 1991, Sprinkel in 1994, Hintze and Axen in 1995 and later, Huntoon and others.[13]

Description

editThe Moenkopi consists of thinly bedded sandstone, mudstone, and shale, with some limestone in the Capitol Reef area. It has a characteristic deep red color and tends to form slopes and benches. The depositional environment varies from fluvial channel and floodplain deposits in the eastern exposures to tidal mudflats in the Cedar Mesa area to deltaic sandstones and shallow marine limestones at Capitol Reef. In eastern Nevada and northwestern Utah, it thickens dramatically, then transitions to the Woodside, Thaynes, and Mahogany formations.[14]

The general deposition setting was sluggish rivers traversing a flat, featureless coastal plain to the sea. The low relief meant that the shoreline moved great distances with changes of sea level or even with the tides. Thickness varies from a feather edge against the Uncompahgre highlands to the east to over 600 metres (2,000 ft) in southwestern Utah. The thickness varies greatly in the Paradox Basin, where the Moenkopi is thin to nonexistent on the crests of salt anticlines and over 400 meters (1,300 feet) thick in the corresponding synclines.[14][2]

The Moenkopi rests unconformably on Paleozoic beds and the Chinle Formation in turn rests unconformably on the Moenkopi. Both unconformities are locally angular unconformities.[15] The lower unconformity corresponds to the regional Tr-1 unconformity and the upper to the regional Tr-3 unconformity. The Tr-1 unconformity represents a hiatus of at least 20 million years while Tr-2 represents a hiatus of about 10 million years.[16]

Members

editMembers differ considerably from east to west, in part because sandstone beds corresponding to marine transgressions are used to define members to the west but cannot be traced to the east.[17] In different regions, by ascending stratigraphic order, the members are:

- Tenderfoot Member. This is everywhere in contact with the Cutler Formation on an angular unconformity. Up to 290 feet (88 meters) thick, it consists of basal conglomerate, gypsum, massive cliff-forming mudstone and silty sandstone.

- Ali Baba Member. This is red conglomeratic sandstone and red siltstone and was laid down by energetic rivers. A distinctive feature is load structures. Sediment sources were apparently the crests of anticlines, and paleocurrent directions are north to northwest, along the corresponding synclines.

- Sewemup Member. This is thinly bedded siltstone, shale, and sandstone, with enough gypsum content to give it a light brown color that contrasts with the darker brown Ali Baba Member.

- Parriott Member. This is distinguished from the light brown Sewemup Member by its multihued brown, red, orange and purple strata. Exposures are geographically limited, appearing only in Richardson Amphitheater, Castle Valley, Sinbad Valley, and Big Bend meander of the Colorado River. This member may be separated from the Sewemup Member by a regional unconformity.

Canyonlands and Glen Canyon area:[18]

- Hoskinnini Member: Sandstone and siltstone. Found only in the southern part of the area.

- Black Dragon Member. Consists of a basal conglomerate; thinly bedded red sandstone, siltstone, and shale deposited in a tidal flat environment; a sandstone sheet; and a second sequence of tidal flat deposits.

- Sinbad Limestone Member. Named for the Sinbad region in the San Rafael Swell. Consists of yellowish limestone deposited by a brief marine transgression.

- Torrey Member. Red beds signifying a return to subaerial deposition.

- Moody Canyon Member. Thinly bedded slope forming siltstone and mudstone with minor evaporites.

San Juan Basin and Tucumcari:[12][20][21]

- Anton Chico Member. Described previously as the red sandstone member of the Santa Rosa Formation, but placed in its own formation after it was recognized to be middle Triassic in age. Subsequently, named as a member of the Moenkopi when its beds were traced west and demonstrated that it was deposited in a single basin with Moenkopi beds in Arizona.

Other members listed in alphabetical order, with asterisks (*) indicating usage by the U.S. Geological Survey and other usages by state geological surveys:[22]

- Holbrook Sandstone Member (AZ*)

- Moqui Member (AZ*)

- Rock Canyon Conglomerate Member (AZ*, NV*, UT*)

- Shnabkaib Member (AZ*, NV*, UT*)

- Timpoweap Member (AZ, NV, UT*)

- Virgin Limestone Member (AZ*, NV*, UT*)

- Winslow Member (AZ)

- Wupatki Member (AZ*)

Places visible

edit(6)-Rounded tan domes of the Navajo Sandstone, (5)-(dark)-layered red Kayenta Formation, (4)-cliff-forming, vertically jointed, red Wingate Sandstone, (3)-slope-forming, purplish Chinle Formation, (2)-layered, lighter-red Moenkopi Formation, and (1)-white, layered Cutler Formation sandstone. Picture from Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

Found in these geologic locations:[22]

- Black Mesa Basin*

- Great Basin province*

- Green River Basin[2]*

- Las Vegas-Raton Basin

- Orogrande Basin

- Palo Duro Basin

- Paradox Basin*

- Piceance Basin*

- Plateau sedimentary province*

- San Juan Basin*

- Uinta Basin*

Found within these parks (incomplete list):

Fauna

editBivalves

editNumerous fossils of bivalves were found in the Olenekian Virgin Limestone Member of the Moenkopi Formation, in south-western Utah. The discovery of 27 species from 18 genera of two subclasses in these sites in 2013 cast doubt on previous claims that the bivalve fauna only recovered in the Middle Triassic after the end-Permian mass extinction.[23] The first subclass, Pteriomorphia, includes mainly genera that survived the mass extinction, while the second, Heteroconchia, is represented mainly by genera that evolved in the Early Triassic.[23]

Pteriomorphia

edit| Pteriomorphs reported from the Moenkopi Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

| Bakevellia | B. cf. exporrecta | South-western Utah |

|

Numerous specimens. | ||

| B. costata | South-western Utah |

|

Numerous left valves. | The absence of right valves may be caused by the "hydrodynamic separation of the differentially vaulted valves or to weaker calcification".[23] | ||

| Eumorphotis | E. venetiana | South-western Utah |

|

One left valve with shell over 18.3 mm long and 21.7 mm high.[23] | ||

| E. ericius | South-western Utah |

|

Several specimens with shells. | The Anisian Pseudomonotis beneckei is a possibly related species.[23] | ||

| E. virginensis | South-western Utah |

|

Several fragmental specimens. | |||

| E. cf. multiformis | South-western Utah |

|

One incomplete left valve. | |||

| Leptochondria | L. nuetzeli | South-western Utah |

|

"One articulated specimen and approximately 50 isolated left valves", all with external shell layer preserved.[23] | ||

| L. curtocardinalis | South-western Utah |

|

Several specimens. | |||

| Modiolus | M. sp. | South-western Utah |

|

One right valve (USNM 543477) 6.5 mm long and 4.3 mm high. | Shell interior is unknown. USNM 543477 have similarities with "Modiolus" sp. from the late Griesbachian of Russia, and Promytilus homevalensis from the early Permian of Australia.[23] | |

| Parallelodon | P.? aff. beyrichii | South-western Utah |

|

Two right valves. | ||

| Promyalina | P. putiatinensis | South-western Utah |

|

Numerous medium-sized specimens, mostly with outer shell layer but eroded to varying degrees. | ||

| Pernopecten | P.? sp. | South-western Utah |

|

One left valve 27 mm long and 27.6 mm high.[23] | ||

Heteroconchia

edit| Heteroconchs reported from the Moenkopi Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

| Arcomya | A.? sp. | South-western Utah |

|

Two steinkerns. | ||

| Heminajas | H.? cf. balatonis | South-western Utah |

|

Few specimens. | Possibly belong to Neoschizodus thaynesianus.[23] | |

| Myoconcha | M. cf. plana | South-western Utah |

|

Several specimens. | Slightly differs from the holotype by greater divergence of the dorsal and ventral margins.[23] | |

| Neoschizodus | N. laevigatus | South-western Utah |

|

One left valve. | ||

| N. praeorbicularis | South-western Utah |

|

One steinkern. | |||

| Permophorus | P. triassicus | South-western Utah |

|

Several specimens (steinkerns). | ||

| Pleuromya | P. prima | South-western Utah |

|

One steinkern. | Tre earliest specimen of the genus.[23] | |

| Protopis | P.? aff. waageni | South-western Utah |

|

One left valve over 10 mm long and 10 mm high.[23] | ||

| Sementiconcha | S. recuperator | South-western Utah |

|

119 steinkerns. | ||

| Trigonodus | T. cf. orientalis | South-western Utah |

|

Several specimens. | ||

| T. cf. sandbergeri | South-western Utah |

|

Several specimens. | |||

| Unicaridum | U.? sp. | South-western Utah |

|

One left valve. | Assigned to Unicaridum due to subelliptical shape and slightly concave central part of the umbo.[23] | |

| Unionites | U.? fassaensis | South-western Utah |

|

Three steinkerns. | ||

| U.? canalensis | South-western Utah |

|

Four steinkerns. | |||

| U.? cf. borealis | South-western Utah |

|

Numerous specimens. | Specimens look similar to the Griesbachian U. borealis from East Greenland, but the type material is poorly preserved, which makes comparison with published specimens difficult.[23] | ||

Vertebrates

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

A diverse fossil vertebrate fauna has been described from the Moenkopi Formation, mainly from the Wupatki Member and Holbrook Member of northern Arizona. Described basal vertebrates include freshwater hybodont sharks, coelacanths, and lungfish. Temnospondyl amphibians are a common component of the fauna. Temnospondyli include Eocyclotosaurus, Quasicyclotosaurus, Wellesaurus, Vigilius, and Cosgriffius. The rhynchosaur Ammorhynchus is known, but rare. Anisodontosaurus is an enigmatic reptile only known from a few tooth-bearing jaws. The poposauroid archosaur Arizonasaurus is known from one relatively complete skeleton and a significant amount of other isolated material. Footprints and several fragmentary body fossils are known from dicynodonts. The footprints of Cheirotherium and Rhynchosauroides are common in the Wupatki Member.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Fillmore 2011, p. 144.

- ^ a b c Lucas 2017.

- ^ Ward 1901.

- ^ Gregory 1917.

- ^ Bassler & Reeside 1921.

- ^ Stewart et al. 1972.

- ^ Williams & Gregory 1947.

- ^ McKee 1951.

- ^ Shoemaker & Newman 1959.

- ^ Stewart 1959.

- ^ Blakey 1974.

- ^ a b Lucas & Hunt 1989.

- ^ For the whole section, except where noted: GEOLEX database Bibliographic References

- ^ a b Fillmore 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Lucas 2017, p. 149.

- ^ Lucas 2017, p. 155.

- ^ Fillmore 2011, p. 142.

- ^ a b Fillmore 2011, pp. 148–154.

- ^ Lucas 2017, p. 151.

- ^ Lucas & Hunt 1987.

- ^ Lucas 2021, p. 231.

- ^ a b GEOLEX database: Moenkopi

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Michael Hautmann, Andrew B. Smith, Alistair J. McGowan, Hugo Bucher (2013). "Bivalves from the Olenekian (Early Triassic) of southwestern Utah: Systematics and evolutionary significance". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (3): 263-293. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.63751. Archived from the original on February 8, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

edit- Bassler, Harvey; Reeside, J.B. Jr. (1921), "Oil prospects in Washington County, Utah" (PDF), Contributions to economic geology, 1921; Part 2, Mineral fuels, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin, vol. 726-C, pp. C87–C107, retrieved 26 May 2020

- Blakey, R.C. (1974). "Stratigraphic and depositional analysis of the Moenkopi Formation, southeastern Utah". Utah Geological and Mineral Survey Bulletin. 104.

- Fillmore, Robert (2011). Geological evolution of the Colorado Plateau of eastern Utah and western Colorado, including the San Juan River, Natural Bridges, Canyonlands, Arches, and the Book Cliffs. University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-004-9.

- Gregory, Herbert Ernest (1917). Geology of the Navajo Country: A Reconnaissance of Parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 23–31. ISBN 978-0341722533. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Lucas, Spencer G. (2017). "Triassic-Jurassic stratigraphy in southwestern Colorado" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 68: 149–158. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Lucas, Spencer G. (2021). "Triassic stratigraphy of the southeastern Colorado Plateau, west-central New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 72: 229–240. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Hunt, Adrian P. (1987). "Stratigraphy of the Anton Chico and Santa Rosa Formations, Triassic of East-Central New Mexico". Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science. 22 (1): 21–33. JSTOR 40024381.* Lucas, S.G.; Hunt, A.P. (1989). "Revised Triassic stratigraphy in the Tucumcari basin, east-central New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; Hunt, A.P. (eds.). Dawn of the age of dinosaurs in the American southwest. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 150–170.

- McKee, E.D. (1951). "Triassic deposits of the Arizona-New Mexico border area" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 2: 85. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Shoemaker, Eugene M.; Newman, William L. (1959). "Moenkopi Formation (Triassic? and Triassic) in Salt Anticline Region, Colorado and Utah". AAPG Bulletin. 43. doi:10.1306/0BDA5E70-16BD-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- Stewart, John H. (1959). "Stratigraphic Relations of Hoskinnini Member (Triassic?) of Moenkopi Formation on Colorado Plateau". AAPG Bulletin. 43. doi:10.1306/0BDA5E73-16BD-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- Stewart, John H.; Poole, F. G.; Wilson, R. F.; Cadigan, R. A. (1972). "Stratigraphy and origin of the Triassic Moenkopi Formation and related strata in the Colorado Plateau region, with a section on sedimentary petrology". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. Professional Paper. 691: 12. doi:10.3133/pp691.

- Ward, Lester F. (Dec 1901). "Geology of the Little Colorado Valley". American Journal of Science. 12 (72). New Haven: 401. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-12.72.401.

- Williams, Herbert E.; Gregory, Norman C. (1947). "Zion National Monument, Utah". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 58 (3): 211. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1947)58[211:ZNMU]2.0.CO;2.

- GEOLEX database entry for Moenkopi, USGS [Accessed 18 March 2006] (public domain text)

- Bibliographic References for Moenkopi [Accessed 18 March 2006]

External links

editMedia related to Moenkopi Formation at Wikimedia Commons