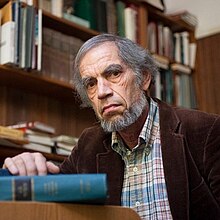

Michael Henry Heim (January 21, 1943 – September 29, 2012) was an American literary translator and scholar. He translated literature from eight languages (Russian, Czech, Serbo-Croatian, German, Dutch, French, Romanian, and Hungarian),[1] including works by Anton Chekhov, Milan Kundera, and Günter Grass. He received his doctorate in Slavic languages and literature from Harvard in 1971, and joined the faculty of UCLA the following year.[2] In 2003, he and his wife used their life savings ($734,000) to establish the PEN Translation Fund.[1][2]

Michael Henry Heim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 21, 1943 Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 29, 2012 (aged 69) Westwood, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Education |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Employer | University of California, Los Angeles (from 1972) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 stepchildren |

Biography

editHeim was born in Manhattan, New York City, on January 21, 1943. His father, Imre Heim, was Hungarian, born in Budapest. He moved to the U.S. in 1939, where he was a music composer (under the pseudonym Imre Hajdu) and a master baker. In New York, Imre was working as a piano teacher when he was introduced to Blanche, Heim's mother, whom he married shortly thereafter. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Imre joined the U.S. Army. At the time of Heim's birth, Imre was stationed in Alabama.[3]: 10–14

Heim's father died when he was four, and he was raised by his mother and step-father in Staten Island. In 1966, he was drafted into the US Army during the Vietnam War. When it was discovered that he was the sole surviving son of a soldier who had died in service, he was relieved from the draft.[4]

During the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Heim was in Prague employed as translator by UNESCO. When the tanks rolled into Prague, he was in the unique position of being able to translate between Czech and Russian, thereby facilitating communications between the Soviet soldiers and the Czechoslovaks on the streets. With his knowledge of German, he was also able to assist a West German television crew in navigating the occupied city and interviewing ordinary Czech citizens, and to warn potential victims that Soviet agents were looking for them.[4]

He was married for thirty-seven years to his wife, Priscilla Smith Kerr, who brought three children of her own, Rebecca, Jocelyn and Michael, into the family from a previous marriage. He died on September 29, 2012, of complications from melanoma.[5][2][6]

Education

editHeim graduated from Curtis High School on Staten Island,[1] where he studied French and German.[5][7] He double-majored in Oriental Civilization and Russian Language and Literature, studying Chinese and Russian at Columbia University as an undergraduate,[4] and worked with Gregory Rabassa, an acclaimed translator.[8] As an American citizen, he had no chance of visiting China after his graduation, so he decided to concentrate on Russian at the postgraduate level. He received his Ph.D. in Slavic Languages from Harvard University in 1971, under the mentorship of Roman Jakobson.[5]

Career

editHeim was one of the finest and most prolific translators of his age. He was also a faculty member of the UCLA Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures for nearly 40 years, being promoted prior to his death to UCLA Distinguished Professor.

Every two years, Heim taught a workshop in literary translation at UCLA's Department of Comparative Literature,[8] which was highly regarded by his students.[5]

Heim served as editor of a translation series published by Northwestern University Press, and was several times a juror for the National Endowment for the Humanities.[9]

After Heim's death, it was revealed with his wife's permission that he was the secret donor behind the PEN Translation Fund,[5] which was set up in 2003 with his gift of $730,000.[10]

Awards and recognition

editHeim garnered unusually wide recognition for his translations, and was considered one of the foremost literary translators of the late twentieth century.[11] He won the 2005 Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator's Prize for German-to-English translation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (Der Tod in Venedig).[12] He received the PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation in 2009.[13] In 2010, he received the PEN Translation Prize for his translation from the Dutch of Wonder (De verwondering, 1962) by Hugo Claus.[14] The same book was also short-listed for Three Percent's Best Translated Book Award.

Besides his celebrated translations, Heim was lauded for his research on 18th-century Russian writers and their philosophies of translation, at a time "when the process of literary creation occurred largely through the prism of translation."[5]

Heim was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2002,[15] and received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006.[16]

Publications

editOriginal works

edit- Heim, Michael Henry (1979). The Russian Journey of Karel Havlíček Borovský (PDF). Munich: Verlag Otto Sagner. ISBN 3-87690-161-8.

- Heim, Michael Henry (1982). Contemporary Czech. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers. ISBN 0-89357-098-2.

- Matich, Olga; Heim, Michael Henry, eds. (1984). The Third Wave: Russian Literature in Emigration. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ardis Publishers. ISBN 0-88233-782-3.

- Heim, Michael Henry (1999). Un Babel fericit (PDF) (in Romanian). Iaşi: Editura Polirom. ISBN 973-683-386-0.

Translations

editFrom Russian

edit- Ageyev, M. (1984). Novel with Cocaine. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24294-5.

- Aksyonov, Vasily (1983). The Island of Crimea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-52431-4.

- Aksyonov, Vasily (1987). In Search of Melancholy Baby. Translated by Michael Henry Heim and Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-54364-5.

- Chekhov, Anton (1973). Karlinsky, Simon (ed.). Letters of Anton Chekhov. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-012263-3. (Republished by Northwestern University Press in 1997 as Anton Chekhov's Life and Thought: Selected Letters and Commentaries. ISBN 0-8101-1460-7.)

- Chekhov, Anton (2003). Chekhov: The Essential Plays. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-76134-8.

- Chekhov, Anton (2010). Easter Week. Mainz, Germany: Shackman Press.

- Chukovsky, Kornei (2005). Erlich, Victor (ed.). Diary, 1901–1969. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10611-4.

- Roziner, Felix (1991). A Certain Finkelmeyer. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-02962-X.

- Sokolov, Sasha (1989). Astrophobia. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. ISBN 0-8021-1087-8.

- Uspensky, Eduard (1993). Uncle Fedya, His Dog, and His Cat. New York: Alfred A. Knopt. ISBN 0-679-82064-7.

From Czech

edit- Čapek, Karel (1995). Talks with T. G. Masaryk. New Haven, Connecticut: Catbird Press. ISBN 0-945774-26-5.

- Hirsal, Josef (1997). A Bohemian Youth. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-1223-X.

- Hrabal, Bohumil (1975). The Death of Mr. Baltisberger. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 0-385-00692-6.

- Hrabal, Bohumil (1990). Too Loud a Solitude. San Diego, California: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-190491-X.

- Hrabal, Bohumil (1995). Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-123810-3.

- Kundera, Milan (1980). The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. New York: Alfred A. Knopt. ISBN 0-394-50896-3.

- Kundera, Milan (1982). The Joke. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-014987-6.

- Kundera, Milan (1984). The Unbearable Lightness of Being. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-015258-3.

- Neruda, Jan (1993). Prague Tales. London: Chatto & Windus.

From Serbian

edit- Kiš, Danilo (1989). The Encyclopedia of the Dead. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-14826-0.

- Kiš, Danilo (1998). Early Sorrows (For Children and Sensitive Readers). New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-1390-0.

- Matvejević, Predrag (1999). Mediterranean: A Cultural Landscape. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20738-6.

- Tišma, Aleksandar (1998). The Book of Blam. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-100235-5.

- Tsernianski, Miloš (1994). Migrations. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-159556-9.

From Croatian

edit- Ugrešić, Dubravka (1991). Fording the Stream of Consciousness. London: Virago Press. ISBN 1-85381-251-X.

- Ugrešić, Dubravka (1992). In the Jaws of Life. Translated by Michael Henry Heim and Celia Hawkesworth. London: Virago Press. ISBN 1-85381-252-8.

- Ugrešić, Dubravka (2005). The Ministry of Pain. London: Saqi. ISBN 0-86356-058-X.

From German

edit- Enzensberger, Hans Magnus (1998). The Number Devil: A Mathematical Adventure. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-5770-6.

- Grass, Günter (1999). My Century. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-100496-X.

- Grass, Günter (2007). Peeling the Onion. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-101477-9.

- Mann, Thomas (2004). Death in Venice. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-057605-7.

- Mora, Terézia (2007). Day In Day Out. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-083264-9.

- Schlink, Bernhard (2008). Homecoming. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-375-42091-6.

From Dutch

edit- Claus, Hugo (2009). Wonder. New York: Archipelago Books. ISBN 0-9800330-1-2.[17]

From French

edit- Kundera, Milan (1985). Jacques and His Master. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-091222-7.

- Troyat, Henri (1986). Chekhov. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24406-9.

From Romanian

edit- Blecher, Max (2015). Adventures In Immediate Irreality. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-1760-4.

From Hungarian

edit- Esterházy, Péter (1992). Helping Verbs of the Heart. London: Quartet Books. ISBN 0-7043-0174-1.

- Konrád, George (1995). The Melancholy of Rebirth: Essays from Post-Communist Central Europe, 1989–1994. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-600252-3.

- Örkény, István (1982). The Flower Show & The Toth Family. Translated by Michael Henry Heim and Clara Gyorgyey. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-0836-2.

References

edit- ^ a b c Fox, Margalit (October 4, 2012). "Michael Henry Heim, Literary Translator, Dies at 69". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c Woo, Elaine (October 7, 2012). "Michael Henry Heim dies at 69; UCLA scholar, translator". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023.

- ^ Allen, Esther; Cotter, Sean; Valentino, Russell Scott, eds. (2014). The Man Between: Michael Henry Heim & A Life in Translation (PDF). Rochester, New York: Open Letter. ISBN 978-1-940953-00-7.

- ^ a b c ""A Happy Babel" interview with Michael Henry Heim". M-Dash. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Sullivan, Meg (October 2, 2012). "Obituary: Michael Heim, 69, professor and award-winning translator of Kundera, Grass". UCLA Newsroom. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013.

- ^ Vroon, Ronald. "Michael Heim: In Memoriam". Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, UCLA. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018.

- ^ "Michael Heim Speaks on Learning Languages". UCLA. October 3, 2012. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Steinman, Louise (September 30, 2001). "Translator Remains Faithful to His 'Unfaithful' Art". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023.

- ^ "In Memoriam: Michael Henry Heim (1943–2012)". UCLA International Institute. October 1, 2012. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012.

- ^ "Translation Fund". PEN American Center. Archived from the original on March 1, 2005.

- ^ Howard, Jennifer (January 17, 2010). "Translators Struggle to Prove their Academic Bona Fides". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ "Michael Henry Heim: Recipient of the 2005 Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator's Prize for Outstanding Translation from German into English". Goethe-Institut USA. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013.

- ^ "Ralph Manheim Medal: 2009 Awardee". PEN American Center. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009.

- ^ "PEN Translation Prize: 2010 Awardee". PEN American Center. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010.

- ^ "Class of 2002 – Fellows". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on February 27, 2006.

- ^ "Michael Henry Heim". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Michael Henry Heim discusses his translation of WONDER by Hugo Claus". Archipelago Books. August 14, 2009. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023 – via YouTube.