Meristodonoides is an extinct genus of hybodont known from the mid-late Cretaceous, with potential records dating back to the Jurassic. It is one of a number of hybodont genera composed of species formerly assigned to Hybodus.[2]

| Meristodonoides Temporal range: Possible Late Jurassic records[1]

| |

|---|---|

| |

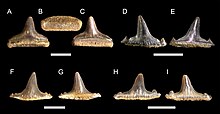

| Teeth of Meristodonoides sp. from the Late Cretaceous of Russia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | †Hybodontiformes |

| Family: | †Hybodontidae |

| Genus: | †Meristodonoides Underwood & Cumbaa, 2010 |

| Type species | |

| †Hybodus rajkovichi Case, 2001

| |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

The genus is primarily known from remains from the Cretaceous of North America and Europe, spanning from the Aptian/Albian to Maastrichtian, making it one of the last surviving hybodont genera, though records of the genus likely extend as far back as the Late Jurassic, based on an undescribed skeleton from the Tithonian of England, and fragmentary teeth from the Kimmeridgian of Poland, England and Switzerland.[3] Other remains of the genus are known from the Coniacian of England, the Aptian-Albian of France,[4] the Campanian of British Columbia, Canada[5] and the Campanian of European Russia.[6]

Taxonomy

editThe type species is M. rajkovichi, which was originally a species in the genus Hybodus. The species, along with other Hybodus species such as H. butleri and H. montanensis, was reassigned to Meristodonoides by Charlie J. Underwood and Stephen L. Cumbaa in 2010.[2][7]

Species

edit- M. butleri (Thurmond, 1971) - Aptian/Albian of Texas[3]

- M. montanensis (Case, 1978) - Campanian of Montana and Wyoming, with similar remains from the Santonian of New Mexico[3][8]

- M. novojerseyensis (Case & Cappetta, 2004[9]) - Campanian of North Carolina,[10] Maastrichtian of New Jersey[3]

- M. rajkovichi (Case, 2001) (type species) - Cenomanian of Minnesota[3]

- M. multiplicatus Cicimurri et al., 2014 - Santonian-Campanian of Mississippi[3]

Ecology

editThe morphology of the teeth suggests an adaptation to tearing prey, with a specialization for restraining fast-swimming prey such as small fish and squid.[3][11] Fossils from the Western Interior Seaway suggest that it preferred nearshore marine environments, being absent from deeper-water areas, with it likely also being able to tolerate brackish and freshwater conditions.[7] In the Gulf Coastal Plain, Meristodonoides teeth are largely found in estuarine deposits. The restriction of Meristodonoides to nearshore habitats, combined with its late occurrence, fits the overall decline in niches occupied by hybodonts throughout the Cretaceous, likely due to them being outcompeted by lamniform sharks in open marine habitats.[11] However, some Meristonoides teeth have also been recovered from deep-water deposits representing open marine environments, such as the Northumberland Formation in Canada.[5]

References

edit- ^ Stumpf, S.; Meng, S.; Kriwet, J. (2022). "Diversity Patterns of Late Jurassic Chondrichthyans: New Insights from a Historically Collected Hybodontiform Tooth Assemblage from Poland". Diversity. 14 (2). 85. doi:10.3390/d14020085.

- ^ a b Underwood, Charlie J.; Cumbaa, Stephen L. (2010). "Chondrichthyans from a Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) bonebed, Saskatchewan, Canada". Palaeontology. 53 (4): 903–944. Bibcode:2010Palgy..53..903U. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00969.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stumpf, Sebastian; Meng, Stefan; Kriwet, Jürgen (2022-01-26). "Diversity Patterns of Late Jurassic Chondrichthyans: New Insights from a Historically Collected Hybodontiform Tooth Assemblage from Poland". Diversity. 14 (2): 85. doi:10.3390/d14020085. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ Guinot, Guillaume; Underwood, Charlie J.; Cappetta, Henri; Ward, David J. (August 2013). "Sharks (Elasmobranchii: Euselachii) from the Late Cretaceous of France and the UK". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (6): 589–671. Bibcode:2013JSPal..11..589G. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.767286. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 84892884.

- ^ a b Cappetta, Henri; Morrison, Kurt; Adnet, Sylvain (2021-08-03). "A shark fauna from the Campanian of Hornby Island, British Columbia, Canada: an insight into the diversity of Cretaceous deep-water assemblages". Historical Biology. 33 (8). doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1681421. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Jambura, Patrick L.; Solonin, Sergey V.; Cooper, Samuel L.A.; Mychko, Eduard V.; Arkhangelsky, Maxim S.; Türtscher, Julia; Amadori, Manuel; Stumpf, Sebastian; Vodorezov, Alexey V.; Kriwet, Jürgen (March 2024). "Fossil marine vertebrates (Chondrichthyes, Actinopterygii, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Akkermanovka (Orenburg Oblast, Southern Urals, Russia)". Cretaceous Research. 155: 105779. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15505779J. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105779. PMC 7615991. PMID 38799703.

- ^ a b Occurrence of the Hybodont Shark Genus Meristodonoides (Chondrichthyes; Hybodontiformes) in the Cretaceous of Kansas, Michael J. Everhart

- ^ "Selachians from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) Hosta Tongue of the Point Lookout Sandstone, central New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science. 2011.

- ^ Case, G.R.; Cappetta, H. Additions to the elasmobranch fauna from the late Cretaceous of New Jersey (lower Navesink Formation, early Maastrichtian). Palaeovertebrata 2004, 33, 1–16

- ^ Case, Gerald R.; Cook, Todd D.; Kightlinger, Taylor (2019-07-31). "A description of a middle Campanian euselachian assemblage from the Bladen Formation of North Carolina, USA". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 7: 69–82. doi:10.18435/vamp29345. ISSN 2292-1389.

- ^ a b Comans, Chelsea M.; Smart, Sandi M.; Kast, Emma R.; Lu, YueHan; Lüdecke, Tina; Leichliter, Jennifer N.; Sigman, Daniel M.; Ikejiri, Takehito; Martínez-García, Alfredo (2024). "Enameloid-bound δ15N reveals large trophic separation among Late Cretaceous sharks in the northern Gulf of Mexico". Geobiology. 22 (1): e12585. doi:10.1111/gbi.12585. ISSN 1472-4669.