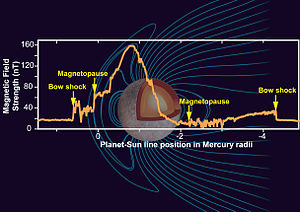

Mercury's magnetic field is approximately a magnetic dipole, apparently global,[8] on the planet of Mercury.[9] Data from Mariner 10 led to its discovery in 1974; the spacecraft measured the field's strength as 1.1% that of Earth's magnetic field.[10] The origin of the magnetic field can be explained by dynamo theory.[11] The magnetic field is strong enough near the bow shock to slow the solar wind, which induces a magnetosphere.[12]

Graph showing relative strength of Mercury's magnetic field. | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Mariner 10 |

| Discovery date | April 1974 |

| Internal field[2][3] | |

| Radius of Mercury | 2,439.7 ± 1.0 km |

| Magnetic moment | 2 to 6 × 1012 T•m3 |

| Equatorial field strength | 300 nT |

| Dipole tilt | 0.0°[4] |

| Solar wind parameters[5] | |

| Speed | 400 km/s |

| Magnetospheric parameters[6][7] | |

| Type | Intrinsic |

| Magnetopause distance | 1.4 RM |

| Magnetotail length | 10–100 RM |

| Main ions | Na+, O+, K+, Mg+, Ca+, S+, H2S+ |

| Plasma sources | Solar wind |

| Maximum particle energy | up to 50 keV |

| Aurora | |

Strength

editThe magnetic field is about 1.1% as strong as Earth's.[10] At the Hermean equator, the relative strength of the magnetic field is around 300 nT, which is weaker than that of Jupiter's moon Ganymede.[13] Mercury's magnetic field is weaker than Earth's because its core had cooled and solidified more quickly than Earth's.[14] Although Mercury's magnetic field is much weaker than Earth's magnetic field, it is still strong enough to deflect the solar wind, inducing a magnetosphere. Because Mercury's magnetic field is weak while the interplanetary magnetic field it interacts with in its orbit is relatively strong, the solar wind dynamic pressure at Mercury's orbit is also three times larger than at Earth.

Whether the magnetic field changed to any significant degree between the Mariner 10 mission and the MESSENGER mission remains an open question. A 1988 J.E.P. Connerney and N.F. Ness review of the Mariner magnetic data noted eight different papers in which were offered no less than fifteen different mathematical models of the magnetic field derived from spherical harmonic analysis of the two close Mariner 10 flybys, with reported centered magnetic dipole moments ranging from 136 to 350 nT-RM3 (RM is a Mercury radius of 2436 km). In addition they pointed out that "estimates of the dipole obtained from bow shock and/or magnetopause positions (only) range from approximately 200 nT-RM3 (Russell 1977) to approximately 400 nT-RM3 (Slavin and Holzer 1979b)." They concluded that "the lack of agreement among models is due to fundamental limitations imposed by the spatial distribution of available observations."[15] Anderson et al. 2011, using high-quality MESSENGER data from many orbits around Mercury – as opposed to just a few high-speed flybys – found that the dipole moment is 195 ± 10 nT-RM3.[16]

Discovery

editBefore 1974, it was thought that Mercury could not generate a magnetic field because of its relatively small diameter and lack of an atmosphere. However, when Mariner 10 made a fly-by of Mercury (somewhere around April 1974), it detected a magnetic field that was about 1/100th the total magnitude of Earth's magnetic field. But these passes provided weak constraints on the magnitude of the intrinsic magnetic field, its orientation and its harmonic structure, in part because the coverage of the planetary field was poor and because of the lack of concurrent observations of the solar wind number density and velocity.[3] Since the discovery, Mercury's magnetic field has received a great deal of attention,[17] primarily because of Mercury's small size and slow 59-day-long rotation.

The magnetic field itself is thought to originate from the dynamo mechanism,[11][18] although this is uncertain as yet.

Origins

editThe origins of the magnetic field can be explained by the dynamo theory;[11] i.e., by the convection of electrically conductive molten iron in the planet's outer core.[19] A dynamo is generated by a large iron core that has sunk to a planet's center of mass, has not cooled over the years, an outer core that has not been completely solidified, and circulates around the interior. Before the discovery of its magnetic field in 1974, it was thought that because of Mercury's small size, its core had cooled over the years. There are still difficulties with this dynamo theory, including the fact that Mercury has a slow, 59-day-long rotation that could not have made it possible to generate a magnetic field.

This dynamo is probably weaker than Earth's because it is driven by thermo-compositional convection associated with inner core solidification. The thermal gradient at the core–mantle boundary is subadiabatic, and hence the outer region of the liquid core is stably stratified with the dynamo operating only at depth, where a strong field is generated.[20] Because of the planet's slow rotation, the resulting magnetic field is dominated by small-scale components that fluctuate quickly with time. Due to the weak internally generated magnetic field it is also possible that the magnetic field generated by the magnetopause currents exhibits a negative feedback on the dynamo processes, thereby causing the total field to weaken.[21] [22]

Magnetic poles and magnetic measurement

editLike Earth's, Mercury's magnetic field is tilted,[9][23] meaning that the magnetic poles are not located in the same area as the geographic poles. As a result of the north-south asymmetry in Mercury's internal magnetic field, the geometry of magnetic field lines is different in Mercury's north and south polar regions.[24] In particular, the magnetic "polar cap" where field lines are open to the interplanetary medium is much larger near the south pole. This geometry implies that the south polar region is much more exposed than in the north to charged particles heated and accelerated by solar wind–magnetosphere interactions. The strength of the quadrupole moment and the tilt of the dipole moment are completely unconstrained.[3]

There have been various ways that Mercury's magnetic field has been measured. In general, the inferred equivalent internal dipole field is smaller when estimated on the basis of magnetospheric size and shape (~150–200 nT R3).[25] Recent Earth-based radar measurements of Mercury's rotation revealed a slight rocking motion explaining that Mercury's core is at least partially molten, implying that iron "snow" helps maintain the magnetic field.[26] The MESSENGER spacecraft was expected to make more than 500 million measurements of Mercury's magnetic field using its sensitive magnetometer.[19] During its first 88 days in orbit around Mercury, MESSENGER made six different sets of magnetic field measurements as it passed through Mercury's magnetopause.[27]

Field characteristics

editScientists noted that Mercury's magnetic field can be extremely "leaky,"[28][29][30] because MESSENGER encountered magnetic "tornadoes" during its second fly-by on October 6, 2008, which could possibly replenish the atmosphere (or "exosphere", as referred to by astronomers). When Mariner 10 made a fly-by of Mercury back in 1974, its signals measured the bow shock, the entrance and exit from the magnetopause, and that the magnetospheric cavity is ~20 times smaller than Earth's, all of which had presumably decayed during the MESSENGER flyby.[31] Even though the field is just over 1% as strong as Earth's, its detection by Mariner 10 was taken by some scientists as an indication that Mercury's outer core was still liquid, or at least partially liquid with iron and possibly other metals.[32]

BepiColombo mission

editBepiColombo is a joint mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to Mercury.[33] It is launched in October 2018.[34] Part of its mission objectives will be to elucidate Mercury's magnetic field.[35][36]

References

edit- ^ "MESSENGER Data from Mercury Orbit Confirms Theories, Offers Surprises". The Watchtowers. 2011-06-06. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ Russell, C. T. (1992-12-03). "Magnetic Fields of the Terrestrial Planets" (PDF). UCLA – IGPP. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ a b c C. T. Russell; J. G. Luhmann. "Mercury: Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere". University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ^ Williams, David, R. "Dr". Planetary Fact Sheets. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ James A. Slavin; Brian J. Anderson; Daniel N. Baker; Mehdi Benna; Scott A. Boardsen; George Gloeckler; Robert E. Gold; George C. Ho; Suzanne M. Imber; Haje Korth; Stamatios M. Krimigis; Ralph L. McNutt Jr.; Larry R. Nittler; Jim M. Raines; Menelaos Sarantos; David Schriver; Sean C. Solomon; Richard D. Starr; Pavel Trávníček; Thomas H. Zurbuchen. "MESSENGER Observations of Reconnection and Its Effects on Mercury's Magnetosphere" (PDF). University of Colorado. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ Reka Moldovan; Brian J. Anderson; Catherine L. Johnson; James A. Slavin; Haje Korth; Michael E. Purucker; Sean C. Solomon (2011). "Mercury's magnetopause and bow shock from MESSENGER observations" (PDF). EPSC – DPS. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ A. V. Lukyanov; S. Barabash; R. Lundin; P. C. Brandt (August 4, 2000). "Energetic neutral atom imaging of Mercury′s magnetosphere 2. Distribution of energetic charged particles in a compact magnetosphere – Abstract". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (14–15). Laurel, Maryland: Applied Physics Laboratory: 1677–1684. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1677L. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(01)00106-4.

- ^ Williams, David R. "Planetary Fact Sheet". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ a b Randy Russell (2009-05-29). "The Magnetic Poles of Mercury". Windows to the Universe. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ a b Jerry Coffey (2009-07-24). "Mercury Magnetic Field". Universe Today. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ a b c Jon Cartwright (2007-05-04). "Molten core solves mystery of Mercury's magnetic field". Physics World. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ Randy Russell (2009-06-01). "Magnetosphere of Mercury". Windows to the Universe. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ Kabin, K.; Heimpel, M. H.; Rankin, R.; Aurnou, J. M.; Gómez-Pérez, N.; Paral, J.; Gombosi, T. I.; Zurbuchen, T. H.; Koehn, P. L.; DeZeeuw, D. L. (2007-06-29). "Global MHD modeling of Mercury's magnetosphere with applications to the MESSENGER mission and dynamo theory" (PDF). Icarus. 195 (1). University of California, Berkeley: 1–15. Bibcode:2008Icar..195....1K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.11.028. S2CID 55170805. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ Lidunka Vočadlo; Lars Stixrude. "Mercury: its composition, internal structure and magnetic field" (PDF). UCL Earth Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ J.E.P. Connerney; N.F. Ness (1988). "Mercury's Magnetic Field and Interior" (PDF). In Faith Vilas; Clark R. Chapman; Mildred Shapley Matthews (eds.). Mercury. The University of Arizona Press. pp. 494–513. ISBN 978-0-8165-1085-6. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ^ Brian J. Anderson; Catherine L. Johnson; Haje Korth; Michael E. Purucker; Reka M. Winslow; James A. Slavin; Sean C. Solomon; Ralph L. McNutt Jr.; Jim M. Raines; Thomas H. Zurbuchen (September 2011). "The Global Magnetic Field of Mercury from MESSENGER Orbital Observations". Science. 333 (6051). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1859–1862. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1859A. doi:10.1126/science.1211001. PMID 21960627. S2CID 26991651.

- ^ Clara Moskowitz (January 30, 2008). "NASA Spots Mysterious 'Spider' on Mercury". Fox News. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ "Science: Mercury's Magnetism". Time. 1975-03-31. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ^ a b Staff Writers (2011-05-20). "Measuring the Magnetic Field of Mercury". SpaceDaily. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ Christensen, Ulrich R. (2006). "A deep dynamo generating Mercury's magnetic field". Nature. 444 (7122). Katlenberg-Lindau: Max-Planck Institute of Germany: 1056–1058. Bibcode:2006Natur.444.1056C. doi:10.1038/nature05342. PMID 17183319. S2CID 4342216.

- ^ K. H. Glassmeier; H. U. Auster; U. Motschmann (2007). "A feedback dynamo generating Mercury's magnetic field". Geophys. Res. Lett. 34 (22): L22201. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3422201G. doi:10.1029/2007GL031662.

- ^ D. Heyner; J. Wicht; N. Gomez-Perez; D. Schmitt; H. U. Auster; K. H.Glassmeier (2011). "Evidence from Numerical Experiments for a Feedback Dynamo Generating Mercury{\rsquo}s Magnetic Field". Science. 334 (6063): 1690–1693. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1690H. doi:10.1126/science.1207290. PMID 22194574. S2CID 2350973.

- ^ Randy Russell (2009-05-29). "Mercury's Poles". Windows to the Universe. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ^ Lynn Jenner; Brian Dunbar (2011-06-16). "Magnetic field lines differ at Mercury's north and south poles". NASA. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ^ Giacomo Giampieri; André Balogh (2001). "Modelling of magnetic field measurements at Mercury". Planet. Space Sci. 49 (14–15). Imperial College, London: 163–7. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1637G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.25.5685. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(01)00101-5.

- ^ "Iron 'snow' helps maintain Mercury's magnetic field, scientists say". ScienceDaily. 2008-05-08. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ^ "Mercury's magnetic field measured by MESSENGER orbiter". phys.org. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ Steigerwald, Bill (2009-06-02). "Magnetic Tornadoes Could Liberate Mercury's Tenuous Atmosphere". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center (2009-06-02). "Magnetic Tornadoes Could Liberate Mercury's Tenuous Atmosphere". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ Brian Ventrudo (2009-06-03). "How Magnetic Tornadoes Might Regenerate Mercury's Atmosphere". Universe Today. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ Kerri Donaldson Hanna. "Mercury's Magnetic Field" (PDF). University of Arizona – Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ David Shiga (2007-05-03). "Molten core may explain Mercury's magnetic field". New Scientist. Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (2008-01-18). "European probe aims for Mercury". The European Space Agency (Esa) has signed an industrial contract to build a probe to send to the planet Mercury. BBC News. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ "ESA Science & Technology: Fact Sheet". esa.int. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Staff (2008). "MM - BepiColombo". Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Archived from the original on 2016-11-13. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ K. H. Glassmeier; et al. (2010). "The fluxgate magnetometer of the BepiColombo Mercury Planetary Orbiter". Planet. Space Sci. 58 (1–2): 287–299. Bibcode:2010P&SS...58..287G. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2008.06.018.