Merab Kostava (Georgian: მერაბ კოსტავა) (May 26, 1939 – October 13, 1989) was a Georgian dissident, musician and poet; one of the leaders of the National-Liberation movement in Georgia. Along with Zviad Gamsakhurdia, he led the dissident movement in Georgia against the Soviet Union and was active in protests for an independent Georgia, until his death in a car crash in 1989.[1]

Merab Kostava | |

|---|---|

| მერაბ კოსტავა (Georgian) | |

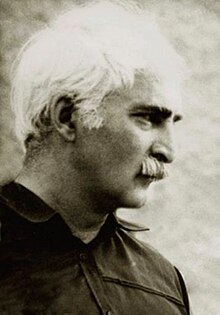

Kostava in 1988 | |

| Born | 26 May 1939 |

| Died | 13 October 1989 (aged 50) |

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Known for | Soviet and Georgian dissident |

| Signature | |

Life

editKostava was born in 1939 in Tbilisi, of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, USSR (the current capital of Georgia). In 1954, Kostava and Zviad Gamsakhurdia founded the Georgian youth underground organization "Gorgasliani," a tribute to Vakhtang Gorgasali, the medieval Georgian king who supposedly founded the capital, Tbilisi.[2] Between 1956 and 1958 Kostava, together with Gamsakhurdia and several other members of this organization were jailed by the KGB for "anti-Soviet activity." The charges against Kostava and Gamsakhurdia included the dissemination of anti-communist literature and proclamations.[citation needed]

Kostava graduated from the Tbilisi State Conservatoire in 1962. From 1962–1977 he was a teacher at a local music school in Tbilisi.[citation needed]

In 1973, Kostava and Gamsakhurdia established the Initiative Group for defence of Human Rights. In 1976 Kostava co-founded the Georgian Helsinki Group (later renamed the Georgian Helsinki Union in 1989). From 1976–1977 and 1987–1989 Kostava was a member of the Governing Board of the abovementioned human rights organization. After 1975 Kostava was a member of Amnesty International.[citation needed]

In 1977, Kostava and Gamsakhurdia were arrested and jailed, charged with spreading anti-Soviet propaganda, the result of them raising awareness about the systemic pillaging of Georgian church artifacts and the deportation and subsequent treatment of the Georgian Muslims.[3] In 1978, Kostava and Gamsakhurdia were nominated to the Nobel Peace Prize by the Congress of the USA. They were sentenced to three years in prison and two years in exile to Siberia.[4] Although Kostava was supposed to be released from prison in 1982, he was sentenced to additional three years in camp and two years in exile on 15 December 1981 in controversial circumstances for allegedly "insulting an officer of the law". He was sent to Irkutsk to serve his sentence and began the hunger strike in protest, which in overall lasted for 13 monthes.[5][6]

Kostava was released from prison in May, 1987.[7][8] In 1988, he co-founded the Society of Saint Ilia the Righteous and was one of the leaders of this political pro-independence organization. From 1988–1989 he was one of the organizers and active participants of most (if not all) peaceful pro-independence political actions within the Georgian SSR. On April 9, 1989 Kostava was jailed again but was released after 45 days under public pressure.[citation needed]

Merab Kostava was active in the underground network of Samizdat publishers, co-publisher of the Georgian underground periodical "Okros Satsmisi" ("The Golden Fleece"). He was the author of many important literary and scientific works.[citation needed]

Death

editOn October 13, 1989, Merab Kostava died in a car crash near Boriti under suspicious circumstances.[9] In 2013, he was posthumously awarded the title and Order of National Hero of Georgia.[10]

Remembrance

editThere are streets named after Merab Kostava in Tbilisi, Batumi, Rustavi and Shindisi.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ "Merab Kostava, 50, a Soviet Rights Figure". New York Times. October 14, 1989. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. London: Reaktion Books. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-78-023030-6.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation (Second ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 309, 319. ISBN 978-0-25-320915-3.

- ^ "Soviet Gives Georgian Dissidents 3 Years in Jail". New York Times. May 20, 1978. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Implementation of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe: Findings and Recommendations Seven Years After Helsinki : Report. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1982. p. 148.

- ^ "შიმშილობის ისტორიები საქართველოში". Radio Freedom. November 9, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Suny. The Making of the Georgian Nation. p. 320.

- ^ "Prominent Georgia Dissident Reported Released in Soviet". New York Times. May 3, 1987. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Rayfield. Edge of Empires. p. 379.

- ^ Kirtzkhalia, N. (October 27, 2013). "Georgian president awards National Hero title posthumously to Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava". Trend. Retrieved January 14, 2015.