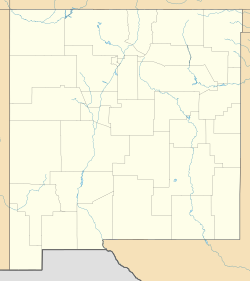

Martinez Hacienda, also known as Hacienda de los Martinez, is a Taos County, New Mexico hacienda built during the Spanish colonial era. It is now a living museum listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is located on the bank of the Rio Pueblo de Taos.

Severino Martinez House | |

Family chapel in Martinez Hacienda | |

| Location | 2 mi. from Taos Plaza, on the Lower Ranchitos Rd., Taos, New Mexico |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°24′1″N 105°36′32″W / 36.40028°N 105.60889°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1804 |

| Architectural style | Hacienda |

| NRHP reference No. | 73001153[1] |

| NMSRCP No. | 202 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 23, 1973 |

| Designated NMSRCP | September 25, 1970 |

Name

editAccording to Miriam Webster, Hacienda meant a "large landed estate" in Spanish during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Its origin is the Old Spanish word facienda, which came from a Latin word that meant to do or things to be done.[2] Often, Native Americans were brought on as "free wage" laborers.

-

Spanish colonialization in 1819

History

editDon Antonio Severino Martinez, also known as Severino Martinez, bought the property about 2 miles southwest of the Taos Plaza in 1804,[3] after relocating his family from Abiquiu to Taos that year.[4][nb 1] At first the building was a four-room dwelling and then it grew as Martinez became more successful.[7] It was made of thick adobe walls, without exterior windows. The hacienda had 2 inner courtyards, or placitas, around which a total of 21 rooms were built. It was constructed as a fortress for protection against attacks by Plains tribes,[3][8][nb 2] such as Comanche and Apache raiders. When there was a threat of violence, the livestock were brought into the courtyards of the hacienda for safety.[10]

Martinez married Maria del Carmel[6][7] Santistevan[11] or Maria del Carmen Santisteban[12] in Abiquiu in 1787. They had six children together, all of whom lived after the death of their parents.[7] He was alcalde (mayor) of Taos, a trader and merchant.[3]

Owning five square miles of land,[nb 3] it was the largest Taos Valley hacienda and was a working ranch and farm. Severino raised pigs, goats, oxen, mules, burros, horses and sheep. Crops included corn, squash, wheat, peas and chilis. Severino had acquired Navajo and Ute workers for ranch and agricultural work. Maria managed 30 Native American servants on the hacienda, including women who made finished woven or knitted goods from raw wool and tanned leather. The men, women and children who served on the farm were acquired from Native American or Mexican traders.[15]

During the Spanish colonial period, goods were either made locally or transported from Mexico City to Taos along the Spanish El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro trade route, of which the hacienda was the final northerly stop. El Camino Real trade is depicted in the hacienda museum's exhibits.[10][16][nb 4] He also traded goods along the Santa Fe Trail after it opened up in 1821.[13]

Severino Martinez built a flourishing mercantile business trading goods from Northern New Mexico, allowing him to send[citation needed][nb 5] his son Antonio José Martínez to study for the priesthood in Durango, Mexico.[18] Antonio José was a spiritual leader in Taos from 1826 to 1867.[3]

Severino lived at the hacienda until his death in 1827.[3] In his will, Severino left his "vast" fortune, most of which was made through trade through Chihuahua, Mexico,[19] to his six children, a nephew and 2 emancipated female servants. One of the emancipated women was his half-sister by his father.[20] The Martinez family held on to the property when Mexico took control of New Mexico from Spain, and again when it became a United States territory and state. It was sold in 1931 outside of the family and over the years fell into disrepair.[7] It was purchased and reconstruction began in 1961 by Jerome Milord and his family.[6] In 1969[7] or 1972[21] it was sold to the Kit Carson Memorial Foundation who restored the property.[7] The hacienda was fully restored by 1982 to its state in 1820.[6]

-

Bridge, stables and the hacienda in the background

-

First courtyard, where most of the family activities occurred

-

La Cocina, or kitchen

Museum

editNow owned by the Taos Historic Museums,[22] it is a living museum honoring the contributions of the early Hispanic settlers in the Taos Valley.[3] It is particularly focused on life during the 1820s under Spanish colonial rule. For instance, the weaving exhibits display wool died with vegetable based tints. And the hacienda's interior walls are white washed with tierra blanca, which is a mixture of micaceous clay and wheat paste.[8]

It is one of the few remaining Spanish colonial haciendas that is open to the public throughout the year in the United States.[3]

-

Buffalo and beaver fur exhibit

-

Santos room

-

Gift shop

It hosts the annual Taos Trade Fair in late September to reenact Spanish colonial life and celebrate the trade among mountain men, Native Americans and Spanish settlers. Demonstrations are performed of blacksmiths, wood carvers and weavers.[3][23] In addition to a working weaving room, there is also a blacksmith shop within the museum.[16]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Author Roy A. Archuleta stated that the family moved to Taos in 1802, and did not buy the property for the future hacienda until 1804.[5] The document Some History of the la Hacienda de los Martinez, produced as part of the walking tour for the hacienda states that Severino came to Taos in 1803, bought the land, and brought his family to Taos in 1804.[6]

- ^ Per Hal E. Jackson, "If other communities had some contact with Plains Indians, the Taos (and Pecos) Pueblo had more. Taos was made the site of an annual trade fair as early as 1723, when Plains Indians brought their buffalo hides and captured Indians to exchange for Spanish goods. In 1760 Tamarón reported an attack on Taos by three thousand Comanche warriors... the Comanches continued their attacks into the nineteenth century, striking as far south as Durango, Mexico.[9]

- ^ Part of his land holdings were obtained through the Arroyo Hondo Land Grant, located 10 miles northwest of Taos.[13] As Alcalde of Taos, he may have had a conflict of interest in water rights issues that he negotiated for the Arroya Hondo Land Grant area.[14]

- ^ Martinez made much of his fortune through trade with Chihuahua, Mexico. Using a caravan of his horses and mules, Martinez shipped animal hides and wool blankets, rugs and clothing to the Mexican city. In return he traded for manufactured goods, like medicine, cotton, silk, books and other goods to sell or trade.[6]

- ^ According to Ray John de Aragon, "He had paid for all his studies until March 9, 1820, when he received a scholarship of royal grace."[17]

References

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Hacienda. Merriam Webster Dictionary. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lesley S. King (2 November 2010). Frommer's Santa Fe, Taos and Albuquerque. John Wiley & Sons. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-470-94629-9.

- ^ Ray John De Aragon (January 2006). Padre Martinez and Bishop Lamy. Sunstone Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-86534-506-5.

- ^ Roy A. Archuleta (2006). Where We Come from. Where We Come From, collect. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4243-0472-1.

- ^ a b c d e Some History of la Hacienda de los Martinez. Hacienda de los Martinez. Made available July 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Four & Twenty Photographs: Stories from Behind the Lens. UNM Press. 2007. p. PT87. ISBN 978-0-8263-4094-8.

- ^ a b Kim Grant (1 January 2007). Santa Fe, Taos & Albuquerque. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-74059-965-8.

- ^ Hal E. Jackson (2006). Following the Royal Road: A Guide to the Historic Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. UNM Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8263-4085-6.

- ^ a b Sharon Niederman (4 February 2013). Explorer's Guide Santa Fe & Taos: A Great Destination (Eighth Edition) (Explorer's Great Destinations). The Countryman Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-58157-142-4.

- ^ Ray John De Aragon (2012). Enchanted Legends and Lore of New Mexico. The History Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-60949-572-5.

- ^ Angelico Chavez (1981). But Time and Chance: The Story of Padre Martinez of Taos, 1793-1867. Sunstone Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-913270-95-0.

- ^ a b Denise Holladay Damico (2008). "El Agua Es la Vida" (water is Life): Water Conflict and Conquest in Nineteenth Century New Mexico. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-549-70117-0.

- ^ Denise Holladay Damico (2008). "El Agua Es la Vida" (water is Life): Water Conflict and Conquest in Nineteenth Century New Mexico. pp. 45–50. ISBN 978-0-549-70117-0.

- ^ Elspeth Leacock; Susan Washburn Buckley (2001). Places in Time: A New Atlas of American History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-395-97958-7.

- ^ a b Eric B. Wechter; Andrew Collins (2011). Santa Fe, Taos & Albuquerque: Where to Stay and Eat for All Budgets - Must-see Sights and Local Secrets - Ratings You Can Trust. Fodor's Travel Publications. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-307-48055-2.

- ^ Ray John De Aragon (January 2006). Padre Martinez and Bishop Lamy. Sunstone Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-86534-506-5.

- ^ Ray John De Aragon (January 2006). Padre Martinez and Bishop Lamy. Sunstone Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-86534-506-5.

- ^ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2007). Roots of Resistance: A History of Land Tenure in New Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8061-3833-6.

- ^ Angelico Chavez (1981). But Time and Chance: The Story of Padre Martinez of Taos, 1793-1867. Sunstone Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-913270-95-0.

- ^ Book talk. The League. 1994. p. iii.

- ^ "Taos Historic Museums to honor four with awards". The Taos News". June 9, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Frommer's (22 May 2012). AARP New Mexico. John Wiley & Sons. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-118-26833-9.

Further reading

edit- Marc Treib (1993). "Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico". The Hispanic Dwelling (using Martinez Hacienda as an example). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- David J. Weber; Anthony Richardson; Skip Miller (1996). On the edge of empire: the Taos hacienda of los Martínez. Museum of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-89013-299-9.

External links

edit- Taos Historic Museums - official site