Marlin is a city in Falls County, Texas, United States. Its population was 5,462 at the 2020 census.[4] Since 1851, it has been the county seat of Falls County. Marlin has been given the nickname "The Hot Mineral Water City of Texas" by the 76th Texas State Legislature.[5] Mineral water was discovered there in 1892.

Marlin, Texas | |

|---|---|

Downtown Marlin, Texas (2024) | |

| Nickname: The Mineral Water City of Texas | |

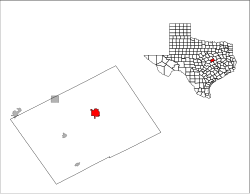

Location of Marlin, Texas | |

| Coordinates: 31°18′24″N 96°53′33″W / 31.30667°N 96.89250°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Falls |

| Settled | 1850 |

| Incorporated | 1867 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.57 sq mi (11.83 km2) |

| • Land | 4.52 sq mi (11.70 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) |

| Elevation | 394 ft (120 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 5,462 |

| • Density | 1,235.55/sq mi (477.07/km2) |

| Demonym | Marlinite |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | 76661 |

| Area code | 254 |

| FIPS code | 48-46740[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2411037[2] |

| Website | marlintx |

History

editEstablishment and antebellum era (1851–1861)

editThe city of Marlin is located 4 miles (6 km) east of the Brazos River, which runs through the center of the county. The low falls on the river southwest of present-day Marlin was the site of Sarahville de Viesca, established in 1834 by Sterling C. Robertson.

The act of the state legislature creating Falls County that passed on January 28, 1850, established Viesca (renamed Fort Milam) as the county seat. Citizens petitioned to choose their own location and a vote was held on January 21, 1851, that established the county seat at Adams, near the home of Dr. Allensworth Adams. On March 22, 1851, the Falls County commissioners court voted to rename Adams the "Town of Marlin" to honor former Robertson County alcalde John Marlin.[6] The new town of Marlin was laid out around a courthouse square and a log courthouse was constructed, which also served as a school and church. In 1854, a new courthouse was constructed for $5,000; it was painted white with dark green shutters and a chrome yellow door.[6]

In 1859, the population of Marlin was 2,875 whites, 1,225 slaves, and nine free blacks.[6]

Schools

editEarly schools

editThe first schools in Falls County were private schools established at Marlin. A tuition school, Marlin Male and Female Academy, was located on Ward Street in 1871, north of the courthouse square. The school was renamed and relocated before finally being sold in 1886, only to be destroyed by fire in 1900. A new public brick school was constructed in 1903 and a high school was completed in 1917. The Marlin Independent School District was established in 1923. Nearly half a century before, in 1875, two other schools for African Americans were organized. The two black schools were dependent on state funds, and met in the African and Baptist churches. In 1916, the city council voted to build a school for blacks; later, the Booker T. Washington High School was constructed in 1951 on Commerce Street and designed by the architectural firm of Thomas, Jameson, and Merrill. This school remains standing, but is vacant. The two school districts merged in 1968 into the Marlin Independent School District (MISD). In 1900, the town's Jewish residents organized a Sunday school.[7]

Modern schools

editA high-school commencement ceremony in Texas was called off after the district found that only of five of 33 students were eligible to graduate, officials said Friday. Marlin HS, 30 miles southeast of Waco, had been set to pass out diplomas on Thursday May 26, 2023, before the MISD revealed that a number of pupils "did not meet requirements due to attendance or grades." In announcing the ceremony postponement, Superintendent Darryl Henson said that students in his district "will he held to the same high standard as any other student in Texas."

"We maintain high expectations, not as an imposition, but as a show of faith in our students' abilities," Henson said in a statement to the community. Superintendent Henson and his staff audited student files this past weekend to find only five were eligible to graduate, district spokesperson Leah Wayne told NBC News on Friday. The ineligibility stemmed from a myriad of reasons, including failing grades, attendance, verification and documentation issues.[8]

Reconstruction era (1865–1877)

editThe town of Marlin was formally incorporated by the state legislature on January 12, 1867. Two former slaves served as elected or appointed officials in Marlin: Nelson Denson and Lige Moore.[6] The Houston & Texas Central Railway reached Marlin on 1871 as a stop on the "Waco Tap" line that extended northwest from Bremond (Robertson County) to Waco. The location of the depot on the eastern side of the town led to the development of a commercial district eastward from the courthouse square along Live Oak Street.

In 1875, the 1854 courthouse burned and a new brick courthouse was constructed. The courthouse was badly damaged in a storm in 1886 and replaced with a new structure designed by architect Eugene T. Heiner.[6]

The mineral water era (1890s–1960s)

editIn 1891, the City of Marlin issued bonds worth $25,000 to drill an artesian well. Hot mineral water was accidentally discovered and later alleged to have medicinal properties. To harness the potential benefit of these "healing waters", the first bath house was constructed in 1895, with several others to follow. A least two of those early houses had large swimming pools with ornate, covered buildings. Other bath houses were subsequently constructed that included individual bathing areas with marble tubs and cooling rooms with available massages for a full spa treatment. Thousands were soon attracted to Marlin to "take the cure."[6]

While Marlin had a number of small hotels in the 19th century, the construction of the three-story Arlington Hotel in 1895 demonstrated the economic impact and potential of the mineral-water industry. The hotel and adjacent bathhouse burned in January 1899, but were both replaced with more elaborate structures that opened in 1901.[6] The new Arlington Hotel hosted notable community events and statewide conventions. Other than the Hilton and the numerous boarding houses (such as Captain Bourrupt's and the Harris Houses), the town had several other hotels, among them the Fannin, the Majestic, and the Imperial; most were on Coleman Street and within a few blocks of the public hot water fountain and the mineral water wells—on a sort of bath-house row.

In 1929, Conrad Hilton began construction of a Hilton Hotel that was opened on May 27, 1930, at a cost of $375,000 and to which Marlin citizens and businesses contributed $50,000.[6] The nine-floor, 110-room hotel remains the tallest building in Marlin and was built on Coleman Street across from the Marlin Sanitarium Bathhouse, which burned in the early 1990s. The hotel was connected to the bathhouse by a tunnel that has not been filled in, but is inaccessible. Mr. Hilton's first venture into the hotel business that featured several hotels in Cisco, Mineral Wells, El Paso, and Marlin were not successful, and Mr. Hilton sold those hotels in the 1930s. The Marlin Hilton was bought by the Moody’s of Galveston and later known as the Falls Hotel, then bought by the Smithwicks. It has been closed since the late 1960s as a hotel, but parts of the first floor have held small businesses-beauty shops, an optometrist's office, an insurance agency, and restaurants. One such restaurant, the Cactus, occupied its space for about 10 years until about 2016. For many years, the first-floor ballroom also featured class reunions and school dances, as well as public outside auction house usages. None of those businesses occupy the hotel at present. The hotel structure still stands, but is unoccupied. In recent years, sporadic renovations have occurred.

Along with the decline of the hot mineral water industry after World War II and the advent of penicillin, many of the bath-house-related businesses closed and those older structures were gradually demolished or reconfigured. Most of the remnants of the bath-house businesses had closed by the late 1960s. In the early 1980s, a short-lived revival arose with some new bathing structures that did not succeed, and neither did one other attempt at that industry's revitalization in that 1990s. Only the Buie-Allen Hospital (circa 1912), now closed, and a very few former boarding houses remain as apartments, as well as some of the intact late 19th-century commercial district and numerous early 20th-century residences constructed by doctors and many others who served the bath-house clientele. Hot mineral water can still usually be obtained from a fountain outside the Marlin Chamber of Commerce in the 1929 pavilion when the city maintains that access. The former location of one of the several bath houses, the Sanitarium Bath House (burned down by accidental arson), is now a small city park featuring a gazebo that is adjacent to the old Houston and Texas Central railroad tracks. Those tracks are currently owned by the Union Pacific Railroad. The waters remain and at least three wells are still active, but not accessible. The local three-story Falls Community Hospital has heated (as of the 1980s) its structure via the mineral water. The active Falls County Historical Commission has an extensive museum. Adjacent to the museum is a lively, active theater group, the Palace Theatre, that features plays and dinner-house productions, as well as occasional outside professional entertainment.

Marlin sports

editMarlin spring training (1904–1918)

editMarlin's mild climate, hot mineral water baths, and proximity by train to Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio made it an appealing spring training location for Major League Baseball teams. Four different teams trained in Marlin from 1904 to 1918: Chicago White Sox, St. Louis Cardinals, Cincinnati Reds, and New York Giants. Players stayed at the Arlington Hotel, which is no longer standing.

In the same era, Marlin was home to minor league baseball. The Marlin Marlins (1916–1917) and Marlin Bathers (1923–1925) played as members of the Class D level Central Texas League and Texas Association.[citation needed]

Chicago White Sox (1904)

editThe Chicago White Sox baseball team visited "Marlin Springs" from March 7 to March 17, 1904, as part of their spring training tour of the South.[9] The team's selection of Marlin can be credited to Ted Sullivan. The Chicago Tribune quoted Sullivan in an article published on February 7, 1904: "If I had looked the United States over for a spring training ground for a ball club, I do not believe I could have found a spot I would pick ahead of Marlin Springs ... [Charles] Comiskey asked me last December when I was coming to Texas to pick him out a place to train. I met a man in Dallas, who told me he left his crutches at Marlin; that he went there suffering with rheumatism. I took a run down to Marlin ... and I found the ideal spot for training grounds. The place has a magnificent hotel. Adjoining this place is a beautiful natatorium equipped with hot sulphur and all kinds of baths... The ball grounds here are on even surface and are only four blocks from the hotel. This is the spot I selected for the Chicago American league club..."[10] The White Sox left Marlin on March 17 "with expressions of regret and of hope that its individuals will be with the White Sox next spring when they return here for a similar stay."[11] Among those on the White Sox who trained in Marlin was George Davis. On the last full day (March 16), Manager Nixey Callahan had the team make a ten-mile round trip walk to the Brazos River after dinner.[12]

St. Louis Cardinals (1905)

editThe St. Louis Cardinals chose "Marlin Springs" as their 1905 spring training site after delays in preparations of a site in Houston. As a result, the Chicago White Sox chose to train in New Orleans.[13] The Cardinals arrived in Marlin on March 6, 1905 and "a large gathering of local fans [were] on hand to welcome the big leaguers."[14] Visits to the hot mineral water baths were a part of the team's daily routine. A St. Louis newspaper reported that "[practice] ends at 4 o'clock and the players get to the bath about 15 minutes later. The baths are hot, and it takes until 5 before the players are cooled off enough to go to the hotel, which is but a couple of steps distant. The baths not only put the players in first-class condition and remove any surplus weight, but they also tend to prevent soreness."[15] The Cardinals broke camp at Marlin on March 17, 1905.[16]

Cincinnati Reds (1906–1907)

editThe Cincinnati Reds baseball team held spring training in Marlin in 1906 and 1907.[17]

New York Giants (1908–1918)

editThe New York Giants baseball team held spring training in Marlin from 1908 to 1918.[18][19]

Modern utilities

editTelephones began appearing in households in Marlin in 1900. Automobiles, electricity, and Lone Star Gas followed shortly. By the mid-1900s, Marlin had a bottling company, stock pens, a brickyard, a turkey-processing plant (the building can still be seen on Williams Street/South Business Highway 6), a saddlery, a water crystallization plant, and a pottery plant.

Modern history

editThe 2000s

editThe loss of major employers in the late 20th and early 21st centuries resulted in a loss of population and a reduction in the city's tax base. While at the census in 2000, Marlin had a population of 6,628 (a modest increase of 242 people from 1990), by 2010, its population had declined to 5,967 residents. According to the US and Texas census, Marlin's largest population peaked at two times in its history, 1950 and 1980, with 7009 being its highest.

First to change hands or close was the Swift turkey-processing plant. Next was Marlin Mills, a carpet-manufacturing company, closed during the 1980s economic decline. A styrofoam company, open in another building in Marlin's industrial park, caught fire and the remains were demolished. A dress-manufacturing plant, which catered to large businesses, such as the airline industry, closed. Wallace, a business form-printing company5 employing hundreds, closed in the mid-2000s. In the early 2000s, 1100 small to medium-sized VA hospitals closed all over the US, one of which was the Thomas T. Connally Veterans Affairs Hospital, a five-floor building located at the corner of Ward and Virginia Streets. The hospital closed in 2005, resulting in the loss of more than 100 jobs, as the economy in Marlin continued to wane.

More recent investments include the construction of a three-story, 60-room Best Western Hotel on Texas State Highway 6, at Farm-to-Market Road 147. However, plans for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to open a medical facility for prisoners at the former Veterans' Affairs Hospital, expected to add an additional 100 to 150 jobs to the Marlin economy, did not materialize. Funds were reallocated to renovate the TDJC hospital in Galveston, which was badly damaged by Hurricane Rita.

2011

editThe Heart of Texas Council of Governments granted the city of Marlin $35,000 to remove 15 dilapidated buildings and structures in the town, which included 300 tons of debris.[20] Over 6 miles (10 km) of water lines were constructed on 20 streets in 2011.[20] The city also started and completed a 500,000-gallon water tower project.

In 2011, the city brought back its Annual Music and Blues Festival, and raised money to revamp the city baseball fields and revive the City Little League, which attracted 160 children that year.[21][22]

The city's crime rate decreased by 45% in 2011.[20]

2015

editOn November 10, 2015, Marlin Chief of Police Darrell Allen died while in office. He had suffered a gunshot while at an off-duty security job in Temple on November 1. The suspect was placed into custody at the scene by other officers working security.[23]

In December 2015, a protest occurred after the city water had been turned off for almost a week. Even after the city and the state had extensively renovated the water treatment system, the man who had worked for the city as the water systems manager, instead of calling for repairs, cut wires when alarms sounded instead of fixing the problems. The state found the disengaging of the systems when they removed panels to determine the problems. This led to a city-wide water crisis that caused the water system to repair extensive damage.

2019

editOn May 4, 2019, Marlin native Carolyn Lofton was elected as the first black woman to serve as mayor. She stated that she was motivated to run "on a desire to uplift and improve the community in which I live for all those who are currently here and those who seek to make a home here."[24]

Geography

editMarlin is located in east-central Falls County at 31°18′29″N 96°53′35″W / 31.30806°N 96.89306°W (31.307975, −96.892975).[25] Texas State Highway 6 runs along the eastern edge of the city, leading northwest 30 miles (48 km) to Waco and southeast 56 miles (90 km) to Bryan. Texas State Highway 7 runs through the center of town as Bridge Street and Live Oak Street, leading east 16 miles (26 km) to Kosse and west 10 miles (16 km) to Chilton.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.6 square miles (11.8 km2), of which 0.04 square miles (0.1 km2), or 1.09%, is covered by water.[26]

Climate

editThe climate in the area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Marlin has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[27]

| Climate data for Marlin, Texas (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1902–1905, 1944–2016) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

98 (37) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

105 (41) |

110 (43) |

112 (44) |

109 (43) |

100 (38) |

90 (32) |

86 (30) |

112 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.1 (15.1) |

63.0 (17.2) |

69.3 (20.7) |

76.9 (24.9) |

83.4 (28.6) |

90.6 (32.6) |

94.5 (34.7) |

95.5 (35.3) |

89.8 (32.1) |

80.6 (27.0) |

69.4 (20.8) |

60.8 (16.0) |

77.7 (25.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 46.3 (7.9) |

50.2 (10.1) |

56.9 (13.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

72.2 (22.3) |

79.5 (26.4) |

82.9 (28.3) |

83.1 (28.4) |

76.9 (24.9) |

67.3 (19.6) |

55.8 (13.2) |

47.9 (8.8) |

65.3 (18.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.5 (0.8) |

37.4 (3.0) |

44.5 (6.9) |

52.1 (11.2) |

61.0 (16.1) |

68.3 (20.2) |

71.3 (21.8) |

70.7 (21.5) |

64.1 (17.8) |

53.9 (12.2) |

42.1 (5.6) |

35.0 (1.7) |

52.8 (11.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

5 (−15) |

15 (−9) |

29 (−2) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

36 (2) |

41 (5) |

25 (−4) |

15 (−9) |

6 (−14) |

−7 (−22) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.32 (84) |

2.87 (73) |

3.74 (95) |

3.35 (85) |

4.97 (126) |

3.01 (76) |

1.84 (47) |

2.23 (57) |

3.05 (77) |

4.34 (110) |

2.94 (75) |

3.44 (87) |

39.10 (993) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.9 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 74.4 |

| Source: NOAA[28][29] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

editHighways and other major roads

edit- Texas State Highway 6, also known as Williams, Craik Streets in city limits

- Texas State Highway 7, also known as Bridge, Live Oak Streets in city limits

- Farm-to-market road 147, starts at Highway 7 and ends at Highway 14 less than four miles southwest of Groesbeck

Airport

editMarlin and Falls County are served by the Marlin Municipal Airport, located 4 miles (6 km) northeast of the center of Marlin.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 500 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,500 | 200.0% | |

| 1890 | 2,058 | 37.2% | |

| 1900 | 3,092 | 50.2% | |

| 1910 | 3,878 | 25.4% | |

| 1920 | 4,310 | 11.1% | |

| 1930 | 5,338 | 23.9% | |

| 1940 | 6,542 | 22.6% | |

| 1950 | 7,099 | 8.5% | |

| 1960 | 6,918 | −2.5% | |

| 1970 | 6,351 | −8.2% | |

| 1980 | 7,099 | 11.8% | |

| 1990 | 6,386 | −10.0% | |

| 2000 | 6,628 | 3.8% | |

| 2010 | 5,967 | −10.0% | |

| 2020 | 5,462 | −8.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 1,530 | 28.01% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 2,320 | 42.48% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 16 | 0.29% |

| Asian (NH) | 23 | 0.42% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 3 | 0.05% |

| Some other race (NH) | 3 | 0.05% |

| Mixed/multiracial (NH) | 146 | 2.67% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,421 | 26.02% |

| Total | 5,462 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 5,462 people, 1,889 households, and 874 families residing in the city.

As of the census[3] of 2000, 6,628 people, 2,415 households, and 1,509 families were residing in the city. The population density was 1,465.4 inhabitants per square mile (565.8/km2). The 2,826 housing units had an average density of 624.8 per square mile (241.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 41.84% White, 44.48% African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.20% Asian, 11.64% from other races, and 1.58% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 18.30% of the population.

Of the 2,415 households, 30.2% had children under 18 living with them, 35.7% were married couples living together, 22.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.5% were not families. About 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.9% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.47, and the average family size was 3.21.

In the city, the age distribution was 33.2% under 18, 7.4% from 18 to 24, 21.3% from 25 to 44, 18.9% from 45 to 64, and 19.3% who were 65 or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.6 males. For every 100 females 18 and over, there were 80.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $21,443, and for a family was $26,861. Males had a median income of $25,220 versus $18,111 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,555. About 27.9% of families and 31.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.8% of those under age 18 and 16.8% of those age 65 or over.

Government and infrastructure

editMunicipal government

editIn December 2015, Damien Eaglin, then the acting police chief, was designated as Marlin chief of police.[34] He replaced Darrell Allen, who was shot and killed in November of that year.[35] Nathan Sodek was named chief in October 2018. He killed himself in September 2019 when Texas Rangers served him a warrant in connection of an investigation of sexual misconduct.[36]

State government

editThe Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) operates the Marlin Unit, a transfer facility for men, in the City of Marlin. The unit opened in June 1992 and was transferred to the Texas Youth Commission (TYC) in May 1995.[37] When it was a part of TYC, the facility, named the Marlin Orientation and Assessment Unit,[38] served as the place of orientation for children of both sexes being committed into TYC from the facility's opening in 1995 to its transfer out of TYC in 2007.[39] In September 2007 the facility was transferred back to the TDCJ.[37] The 2007 conversions of the Marlin unit, to house 600 adult prisoners, had the possibility of improving the economy of Marlin. Around that time Texas officials were examining the possibility of converting a former Veterans Administration medical center in Marlin into a prison unit for psychiatric patients.[40]

The TDCJ also operates the William P. Hobby Unit, a prison for women located southwest of Marlin in unincorporated Falls County and named for former Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby.[41]

Federal government

editThe United States Postal Service operates the Marlin Post Office.[42]

Education

editThe City of Marlin is served by the Marlin Independent School District.

Newspapers

editThe city of Marlin has had several newspapers. The current newspaper that has been serving Marlin since 1890 is the Marlin Democrat,[43] issued every Wednesday. Another newspaper published in the 19th and 20th centuries was The Falls County Freeman, which served the African-American community. The Marlin Ball was established in 1874 by T.C. Oltorf and continued until about 1901. The Falls County Record was popular during the 1940s and 1950s. The Marlin Democrat and The Rosebud News remain the only active newspapers in Falls County.

Culture

editFilmed in Marlin

edit- Leadbelly (1976),[44] starring Roger E. Mosley, was filmed on and around Wood Street in 1974.

- Infamous (2006),[45] starring Sandra Bullock, was filmed around Falls County Courthouse and unrestored homes of Marlin.

- Making New Family Memories in Rural Texas (2016), was filmed in 2016.[46]

Notable people

edit- Danario Alexander, wide receiver for the San Diego Chargers, was born in Marlin and graduated from Marlin High School in 2006

- Ken "Coach" Carter (second home), opened an unconventional boarding school in town in the fall of 2009 which has not been open for years and sits vacant[47]

- Ben Clarkson Connally was appointed a federal district judge by President Harry Truman

- Tom Connally, U.S. senator, 1928–1952, was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during World War II, and member of the U.S. House of Representatives, 1918–1928

- Bruce Curry, world champion boxer, was born in Marlin in 1956

- Bobbi Humphrey, jazz flautist and singer, was born in Marlin in 1950

- Blind Willie Johnson, blues/gospel street musician, had Marlin as his attributed birthplace, although his birth records are lost; his birthplace has also been traced to Beaumont, Texas

- Dan Kubiak, state representative, graduated from Marlin High School in 1957[48]

- Curtis Modkins, running backs coach for Chicago Bears, is a former offensive coordinator for the San Francisco 49ers

- O.L. Rapson was the first manager of the Grand Rapids Hotel and manager of a small store outside of Marlin

- Bob (Robert Jasper) Reeves (1892–1960) was a Western movie actor

- Ben Herbert Rice, Jr. Was a federal district judge appointed by President Harry Truman

- LaDainian Tomlinson, the great San Diego Chargers and New York Jets running back, was born in Marlin; Tomlinson Hill, an unincorporated community just 5 miles (8 km) west of Marlin, is named for antebellum plantation owner James K. Tomlinson, from whom his slaves, including LaDainian Tomlinson's nineteenth century ancestors, took their name

- Phil Wellman, minor league baseball player and manager, is infamous for a 2007 tirade against umpires after his ejection from a game

Photo gallery

edit-

Cotton compress, about 1905

-

Courthouse, about 1905 until 1938

-

Main Street, about 1905

-

"New High School", about 1905

-

Marlin Sanitarium, about 1905

-

Bath houses and Sanitarium, about 1905

-

Falls County Courthouse, March, 2009

-

Fountain running Marlin's hot mineral water

-

Falls Hotel on Coleman St. in 2010

-

Palace Theater

-

Buie-Allen Hospital

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Marlin, Texas

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "MARLIN | Texas Almanac". texasalmanac.com. November 22, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Texas Legislature Online - 76(R) History for HCR 12".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marlin Bicentennial Heritage Committee (1976). Marlin 1851-1976. Waco, Texas: Marlin Chamber of Commerce. p. 17.

- ^ "Marlin, Texas" Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, found in the Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities,

- ^ "Texas school district commencement called off after only of five of 33 prospective students eligible to graduate". NBC News. May 26, 2023. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023.

- ^ "White Sox to Train in South". Topeka State Journal. January 25, 1904. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "Praises White Stocking Camp". Chicago Tribune. February 7, 1904. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "White Sox Break Camp". Chicago Tribune. March 20, 1904. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "Last Day at Marlin Springs". Chicago Tribune. March 17, 1904. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "White Sox to New Orleans". Topeka (Kansas) State Journal. January 2, 1905. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "Cardinals Ready to Begin Practice". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 6, 1905. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "Severe Effects of Training Makes Baseball Veterans Quit". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. March 12, 1905.

- ^ "Baseball Notes". The Pittsburgh Press. March 18, 1905. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ "Cincinnati Reds Spring Training". Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "San Francisco Giants Spring Training". Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Charles C. (1995). John McGraw. Bison Books, reprint from Viking. p. 48. ISBN 0-8032-5925-5.

- ^ a b c "City manager discusses Marlin's progress in 2011 - The Marlin Democrat: News". Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Marlin Blues Festival Returns After Five-Year Hiatus". Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Season opens for Marlin Little League - The Marlin Democrat: Sports". Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Slain Police Chief's Body Returned To Central Texas" (Archive). KWTX-TV. November 11, 2015. Retrieved on January 19, 2016.

- ^ "Carolyn Lofton for Mayor".

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Marlin city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 22, 2016.[dead link]

- ^ "Marlin, Texas Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/ [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "BREAKING NEWS - Eaglin named MPD chief Archived 2016-01-19 at the Wayback Machine." The Marlin Democrat. Thursday December 10, 2015. Retrieved on January 19, 2016.

- ^ "BREAKING NEWS - MPD Chief Allen dies at hospital Archived 2016-01-19 at the Wayback Machine." Marlin Democrat. Thursday November 12, 2015. Retrieved on November 19, 2016.

- ^ "Texas Police Chief Kills Himself After Being Served Warrant". 21 CBS DRW. August 23, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Marlin Unit Archived 2010-07-25 at the Wayback Machine." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on September 22, 2010.

- ^ "Facility Address List." Texas Youth Commission. November 10, 2001. Retrieved on June 24, 2010.

- ^ "How Offenders Move Through TYC." Texas Youth Commission. November 10, 2001. Retrieved on June 24, 2010.

- ^ Ward, Mike. "Texas could get new adult prisons without building them" (). Austin American-Statesman. Tuesday June 5, 2007. Retrieved on January 19, 2016.

- ^ "Hobby Unit Archived 2010-07-25 at the Wayback Machine." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on September 22, 2010.

- ^ "Post Office Location - MARLIN Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on September 22, 2010.

- ^ "The Marlin Democrat". www.marlindemocrat.com. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Filming Location Matching "Marlin, Texas, USA" (Sorted by Popularity Ascending)". IMDb. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "ePodunk". www.epodunk.com. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Fixer Upper | Season 3 Episode 7 | Paw Paw's House".

- ^ "Coach Ken Carter: From Lockout to Open Doors". Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "Daniel Kubiak". cemetery.state.tx.us. Retrieved June 7, 2011.