Marianne and Juliane (German: Die bleierne Zeit; lit. "The Leaden Time"[1] or "Leaden Times"[2]), also called The German Sisters in the United Kingdom,[3] is a 1981 West German film directed by Margarethe von Trotta. The screenplay is a fictionalized account of the true lives of Christiane and Gudrun Ensslin. Gudrun, a member of The Red Army Faction, was found dead in her prison cell in Stammheim in 1977. In the film, von Trotta depicts the two sisters Juliane (Christine) and Marianne (Gudrun) through their friendship and journey to understanding each other. Marianne and Juliane was von Trotta's third film and solidified her position as a director of the New German Cinema.

| Marianne and Juliane | |

|---|---|

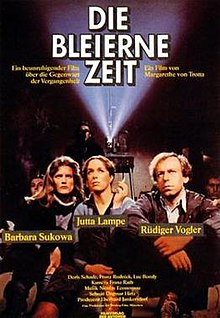

German film poster | |

| Die bleierne Zeit (Germany) | |

| Directed by | Margarethe von Trotta |

| Written by | Margarethe von Trotta |

| Produced by | Eberhard Junkersdorf |

| Starring | Jutta Lampe Barbara Sukowa |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | West Germany |

| Language | German |

Marianne and Juliane also marked the first time that von Trotta worked with Barbara Sukowa. They would go on to work on six more films together.

Plot

editThis article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (April 2021) |

Two sisters, both dedicated to women's civil rights, fight for it in very different ways. The story is interspersed with flashbacks into the sisters' childhood.

Juliane works as a feminist journalist campaigning for a woman's right to abortion while Marianne commits herself to a violent revolutionary terrorist group. The film quickly informs us that Marianne has abandoned her husband and child. Her husband arrives at Juliane's house and states that she must take Jan (their son) because he has to leave the country for work. Juliane is not supportive of her sister's choices because she feels that they are damaging to the women's movement and informs the husband that she does not have time to care for the child. The husband steps out to "go get something", promising to return, but instead takes his life, leaving Jan without a guardian.

Marianne meets with Juliane to discuss her political views with her sister and urge her to join the movement. Juliane informs her of her husband's suicide and of her intention to find a foster home for Jan. Marianne asks her sister to watch over Jan but Juliane replies "You would have me take on the life that you chose to leave", basically stating "so what's not good enough for you is good enough for me". Juliane's refusal does not stop Marianne from continuing in the movement. She is content to commit Jan to foster care because she believes that "any life he has in foster care will be better than the life many children have in third world countries." The sisters' paths continue to cross as Marianne regularly bursts in unannounced to her sister's life. On one occasion, Marianne wakes her and her long-term boyfriend up at 3 a.m., makes coffee for two of her comrades and goes through Juliane's clothes for anything she might like. Soon afterward, it is discovered that Marianne has been arrested and is being held in a high security prison. Juliane goes to visit her sister. When she arrives she is searched and, after being left in the waiting room, the guard returns and informs her that Marianne refuses to see her.

Juliane goes home agonizing over her inability to communicate with her sister and see how she is doing. Her boyfriend suggests that she write to her sister telling her how she feels. The film goes into a flashback of their childhood where we see the closeness of the sisters. Juliane mails the letter and soon after is able to visit her sister. They argue often but Juliane continues to visit her sister. Following a bad argument when Marianne slaps her sister, Marianne is moved to a maximum-security prison where the two are separated by a pane of glass and can only communicate through an intercom.

Juliane becomes so obsessed with her sister and her problems that her own relationships begin to fall apart. Her boyfriend suggests that they take a vacation. While on vacation they see a photo of Marianne on TV but cannot understand what has happened to her because of the language barrier. Juliane runs back to their hotel and calls her parents to find that Marianne has "committed suicide" which Juliane and her father do not accept. Juliane begins an obsessive journey to discover what really happened. This destroys her relationship with her boyfriend of ten years. She ultimately proves to herself that Marianne was murdered but, when she calls the papers with her insights, she is informed that her sister's death is "old news" and nobody cares if it was murder or suicide. Juliane is left with the knowledge but cannot convince the papers to defend the name of a dead terrorist.

Later, Juliane is reunited with Jan because someone attempted to murder him by arson when they found out who his mother was. Juliane takes him back home with her after he had undergone extensive reconstructive surgery. He is aloof and has no interest in having a relationship with his aunt. He has nightmares of the fire that nearly killed him.

The film ends with him walking into Juliane's workroom and tearing up the picture of his mother that is on the wall. Juliane tells him "you are wrong, Jan. Your mother was a great woman. I'll tell you about her". Jan says that he wants to know everything and then yells "Start now! Start now!" The film fades out on Juliane's face looking at him.

Cast

edit- Jutta Lampe as Juliane

- Barbara Sukowa as Marianne

- Rüdiger Vogler as Wolfgang

- Julia Biedermann as Marianne, 16 years

- Ina Robinski as Juliane, 17 years

- Doris Schade as the mother

- Franz Rudnick as the father

- Vérénice Rudolph as Sabine

- Luc Bondy as Werner

Crew

edit- Eberhard Junkersdorf, producer

- Franz Rath, cinematographer

- Dagmar Hirtz, film editor

- Barbara Kloth and Georg von Kieseritzky, production designers

- Monika Hasse and Jorge Jara, costume designers

- Rüdiger Knoll, make-up artist

- Ute Ehmke and Lotti Essid, production managers

- Werner Mink, art department

Reception

editThis film was well received and became a platform for von Trotta as a director of the New German Cinema. Though she was not as highly recognized as her male counterparts, the New German Cinema and the study of the more human side of contemporary political issues (like terrorism in this case) became her focus. In regards to the film, Barton Byg notes, "rather than criticize hysterical responses to terrorism, the film employs its emotive power" (Finn 47). In the United States, the film was pitched to be less about terrorism and the emotional side of the strained relationship but more about a sisterly relationship that was searching for understanding (Finn). The film was not praised universally. It was also criticized for attempting to "hide" its message behind the sister-sister relationship, a message that was empathetic to the plight of the terrorist-activist. Charlotte Delorme, a critic, stated: "If Marianne and Juliane were really what it claims to be it would not have gotten any support, distribution, and exhibition." (Finn)

Acclaimed director Ingmar Bergman named the film as one of his favourite eleven films of all time in 1994.[4]

Accolades

editAt the 38th Venice International Film Festival, von Trotta won the Golden Lion and the FIPRESCI awards, while the actresses who played the title sisters tied for Best Actress. In 1982, the film won the Outstanding Feature Film Award in West Germany, and von Trotta received a special award commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Federal Republic of Germany.

At the Créteil Films de Femmes, an International Woman's Film Festival, 1981, the film won the Prix du Public and Prix du Jury.

References

edit- ^ Brockmann, Stephen (2010-01-01). A Critical History of German Film. Camden House. ISBN 9781571134684.

- ^ Sloan, Jane (2007-03-26). Reel Women: An International Directory of Contemporary Feature Films about Women. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461670827.

- ^ Clarke, David (2006-01-01). German Cinema: Since Unification. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826491060.

- ^ Marshall, Colin. "Ingmar Bergman Names The Eleven Films He Liked Above All Others (1994)". Retrieved 13 June 2015.

Sources

edit- Marianne and Julianne at the IMDb

- Susan E. Linville: Retrieving History: Margarethe von Trotta's Marianne and Juliane, PMLA, Vol. 106, No. 3 (May 1991), pp. 446–458

- Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, no. 29, February 1984, pp. 56–59

- Finn, Carl: The New German Cinema: Music History, and the Matter of Style, University of California Press, 2004