Margaret Aitken[a] (died c. August 1597, Fife), known as the Great Witch of Balwearie, was an important figure in the great Scottish witchcraft panic of 1597 as her actions effectively led to an end of that series of witch trials. After being accused of witchcraft Aitken confessed but then identified hundreds of women as other witches to save her own life. She was exposed as a fraud a few months later and was burnt at the stake.

Background

editPart of the parish of Abbotshall to the south west of Raith and west of Kirkcaldy,[3][4] the small hamlet of Balwearie in Fife had long been associated with supernatural events.[5]

It is recorded that King James V had a nightmare in 1539 that the laird of Balwearie's son, Thomas Scott, visited the king "in the company of devils".[5] The 13th-century physician, Sir Michael Scott of Balwearie, had long since entered folklore as being a wizard.[6]

Great Scottish witch hunt of 1597

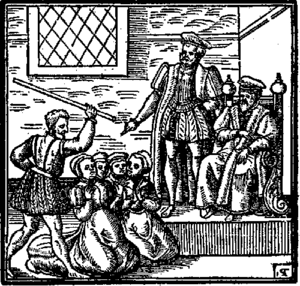

editMargaret Aitken was accused of witchcraft and arrested on suspicion of that crime in Fife c. April 1597.[7][8] Under the threat of extreme torture and to spare her own life,[6] during her confession she claimed to be able to recognise other witches[9] by looking for a special mark in their eyes.[7]

In May 1597, she claimed to know of a convention of 2,300 witches in Atholl.[7] As a result, a special commission was formed with the approval of James VI,[7] and prosecutors took her from town to town to detect witches.[1] During 1597 the only other witch finder used in witchcraft cases was Marion Kwyne who featured in the cases brought against two men and thirteen women in Kirkcaldy; academic Stuart Macdonald[10] speculates this may have been Aitken under an assumed name.[11]

In addition to Aitken looking into the eyes of those accused of witchcraft, the commission also employed the swimming test[7] – almost the only occasion this test was used in Scotland.[7]

"it appears that God hath appointed (for a super-natural signe of the monstrous impiety of the Witches) that the water shal refuse to receive them in her bosom, that have shaken off the sacred Water of Baptisme, and wilfully refused the benefit thereof."

When she reached Glasgow, the minister John Cowper condemned many innocent women to death on her testimony.[12] Any woman suspected of witchcraft was cast into prison and subjected to torture – under which most of them confessed to being guilty.[13] They would then be brought to trial and executed.[13] The exact number of executions carried out by the commission is unknown but is thought to have run into hundreds.[7]

Following a final confession, where Aitken admitted to falsifying her powers, Marion Walker (an active resistor of John Cowper's witch hunts) distributed Aitken's confession, which ultimately brought the period to an end - leading to James I rendering the existing commissions at Falkland Palace invalid.

Aitken's short-lived success also led to imitators such as Anne Ewing in Kirkcaldy who after large-scale witch hunts in Kirkcaldy was loaned by the magistrates of Kirkcaldy to their colleagues in Inverkeithing on condition that she was to return.[14]

Robert Bowes, the English ambassador in Edinburgh, wrote to Lord Burghley in August 1597 that the king was "lately pestered and many ways troubled in the examination of the witches which swarm in exceeding number and (as is credibly reported) in many thousands".[15]

Death

editAround 1 August 1597,[6] Aitken was exposed as a fraud.[9] A sceptical prosecutor took some of those declared guilty and brought them back to Aitken the next day in different clothing. When she declared them innocent, her role as witch-finder was irretrievably undermined and the witch trials stopped.[7]

Taken back to Fife, she stood trial and affirmed that all she had said about herself, and about others, was false.[7] Aitken was burnt at the stake in August 1597.[9][13]

Legacy

editAfter this disastrous episode, James VI revoked the existing commissions on 12 August 1597 via a proclamation by the privy council at Falkland.[6] The outcry over the Aitken affair meant that Scotland would not see another panic for another three decades,[12] but James VI's confidence in pursuing offenders was undiminished.[16]

The king had his mind only bent on the examination and trial of sorcerors, men and women.[16]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Her surname is given as Atkin by academics Lizanne Henderson[1] and Stuart Macdonald.[2]

Citations

edit- ^ a b Henderson (2016), p. 273

- ^ Macdonald (2014), 1561, 1940

- ^ Macdonald (2014), 3805

- ^ Leighton & Stewart (1840), p. 153

- ^ a b Goodare (2002), p. 58

- ^ a b c d Goodare (2002), p. 59

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Goodare (2006), p. 8

- ^ "Welcome to Fife : Great Witch Hunt of Scotland", Welcome to Fife – highlight, retrieved 17 June 2017

- ^ a b c Stilma (2016), p. 228

- ^ "The Rev. Dr. Stuart Macdonald, Professor of Church and Society", Knox College, University of Toronto, archived from the original on 20 August 2017, retrieved 20 August 2017

- ^ Macdonald (2014), 3502

- ^ a b Middleton, Heather (2011), "GWL Glasgow Necopolis Womens Heritage Walk Map" (PDF), Glasgow Women's Library, retrieved 17 June 2017

- ^ a b c Wright (1852), p. 329

- ^ Goodare (2002), pp. 59–60

- ^ John Duncan Mackie, Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 13, pt. 1 (Edinburgh, 1969), p. 73.

- ^ a b Maxwell-Stuart (2014), p. 239

Bibliography

edit- Goodare, Julian (2002), The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context, Manchester University Press, ISBN 9780719060243

- Goodare, Julian (2006), "Aitken, Margaret", in Ewan, Elizabeth; Innes, Sue; Reynolds, Sian (eds.), The biographical dictionary of Scottish women from the earliest times to 2004, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0748617132, OCLC 367680960

- Henderson, Lizanne (2016), Witchcraft and Folk Belief in the Age of Enlightenment Scotland, 1670–1740, Palgrave MacMillan, ISBN 978-1-137-31324-9

- Leighton, John M.; Stewart, James (1840), History of the County of Fife: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, J. Swan

- Macdonald, Stuart (2014), Witches of Fife: Witch-hunting in a Scottish Shire, 1560-1710, Birlinn, ASIN B00GQDQJ96

- Maxwell-Stuart, Peter (2014), The British Witch, Amberley Publishing, ISBN 9781445622187

- Stilma, Astrid (2016), A King Translated: The Writings of King James VI & I and their Interpretation in the Low Countries, 1593–1603, Routledge, ISBN 9781317187745

- Wright, Thomas (1852), The history of Scotland