Manslaughter is a 1922 American silent drama film directed by Cecil B. DeMille and starring Thomas Meighan, Leatrice Joy, and Lois Wilson. It was scripted by Jeanie MacPherson adapted from the novel of the same name by Alice Duer Miller. Art direction and costumes for the film were done by Paul Iribe.[2]

| Manslaughter | |

|---|---|

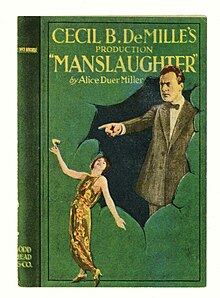

early edition of Alice Duer Miller's novel with images from DeMille's film on cover. | |

| Directed by | Cecil B. DeMille |

| Written by | Jeanie MacPherson |

| Based on | Manslaughter (1921 novel) by Alice Duer Miller |

| Produced by | Cecil B. DeMille Jesse L. Lasky |

| Starring | Leatrice Joy Thomas Meighan Lois Wilson |

| Cinematography | L. Guy Wilky Alvin Wyckoff |

| Edited by | Anne Bauchens |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes (10 reels; 9,061 feet) |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | Silent English intertitles |

| Budget | $385,000[1] |

The film portrays its main character, Lydia Thorne, as a thrill-seeking, self-entitled, and wild woman who does not have a reputation of thinking before acting. She acts selfishly by dancing with other men in the presence of her husband and not providing help to her maid who is in dire straits due to her son's health. She is eventually taken to court after she crashes into a motorcycle cop during a high-speed chase. She is then prosecuted by her husband, Daniel O'Bannon, a lawyer, and is imprisoned for manslaughter. After her sentence, Lydia comes out of jail to find her husband has become an alcoholic.

As part of Lydia's wild life, the film was one of the first to depict an orgy, as well as other acts considered debaucherous in upper-class society.[3] Manslaughter is generally cited as being the first American feature film to show an erotic kiss between two members of the same sex.[4]

The novel was adapted again by Paramount in 1930 and 1931 in French.[2]

Plot

editA wild, wealthy woman (Joy) is brought to heel by a sermonizing district attorney after she accidentally hits and kills a motorcycle cop.

Cast

edit- Leatrice Joy as Lydia Thorne

- Thomas Meighan as Daniel J. O'Bannon

- Lois Wilson as Evans (Lydia's maid)

- John Miltern as Gov. Stephan Albee

- George Fawcett as Judge Homans

- Julia Faye as Mrs. Drummond

- Edythe Chapman as Adeline Bennett

- Jack Mower as Drummond (policeman)

- Dorothy Cumming as Eleanor Bellington

- Casson Ferguson as Bobby Dorest

- Michael D. Moore as Dicky Evans (as Mickey Moore)

- James Neill as Butler

- Sylvia Ashton as Prison matron

- Raymond Hatton as Brown

- Mabel Van Buren as Prisoner

- Ethel Wales as Prisoner

- Dale Fuller as Prisoner

- Edward Martindel as Wiley

- Charles Ogle as Doctor

- Guy Oliver as Musician

- Shannon Day as Miss Santa Claus

- Lucien Littlefield as Witness

- J. Farrell MacDonald (uncredited)

Production

editThe production of this film was completed during a time when films were taking on tremendous set processes and crews. Film shooting processing was becoming more complex, involving actors and actresses, producers, set developers, screenwriters, camera-crew and lighting, and numerously more parts. It was a film created using continuity filming which involves continuing a screen from different points of view.[5]

According to Leatrice Joy, the filming of the car chase scene was extremely nerve-wracking because she herself had to drive the car, which had been fitted with a platform to support two cameramen and the director, plus equipment. Their safety depended entirely upon her skills as a motorist.[6] Joy did most of her own driving, though in some shots the car was driven by stunt double Leo Nomis.[7] During the shooting of a prison sequence, Joy burned her hand accidentally with soup in a prop cauldron; assistant director Cullen Tate had neglected to inform her that the soup was scalding hot.[6]

Stuntman Leo Noomis broke his pelvis and six of his ribs during a stunt that required him to crash a motorcycle into a car.[8]

Reaction

editManslaughter is thought of by historians as one of De Mille's lesser efforts as a director. Historian Kevin Brownlow notes that Joy and Wilson "both give far better performances than the film deserves."[9] "It is hard to believe that such a crude and unsubtle film could come from a veteran like De Mille," said a 1963 Theodore Huff Society program note for the film, "harder still to believe that this came from the same year that Orphans of the Storm, Down to the Sea in Ships, and Foolish Wives. The amateurish and crudely faked chase scenes that start the film are of less technical slickness than Sennett had been getting ten years earlier. Manslaughter is exactly the kind of picture that the unknowing regard as typical of the silent film - overwrought, pantomimically acted, written in the manner of a Victorian melodrama, the kind of film that invites laughter at it rather than with it."[9]

When a print was screened by William K. Everson for Joy's daughter's birthday, the star of the film attended and saw it for the first time in forty years. According to Kevin Brownlow, "Miss Joy thought it hilarious."[9]

Preservation

editComplete prints of Manslaughter are held by:

- George Eastman Museum (on 35 mm and 16 mm)

- Library of Congress (on 35 mm and 16 mm)

- Museum Of Modern Art

- EYE Filmmuseum.[10]

- The Paul Killiam Collection at Worldview Entertainment[1]

References

edit- ^ a b "Progressive Silent Film List: Manslaughter". Silent Era. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^ a b "Manslaughter". afi.com. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "Alice Duer Miller | American author". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Robertson, Patrick (1993). The Guinness Book of Movie Facts & Feats (5th ed.). Abbeville Press. p. 63. ISBN 1558596976.

- ^ Magliano, Joseph P.; Zacks, Jeffrey M. (November 2011). "The Impact of Continuity Editing in Narrative Film on Event Segmentation". Cognitive Science. 35 (8): 1489–1517. doi:10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01202.x. ISSN 0364-0213. PMC 3208769. PMID 21972849.

- ^ a b Brownlow, K.; The parade's gone by...; University of California Press, 1976; p. 185

- ^ "Manslaughter (1922) - IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Kozlovic, Anton Karl (January 2, 2014). "DeMille and Danger: Seven Heuristic Taxonomic Categories of His Hollywood (Mis)Adventures". European Journal of American Studies. 9 (9–1). doi:10.4000/ejas.10165 – via journals.openedition.org.

- ^ a b c Brownlow, K.; The parade's gone by...; University of California Press, 1976; p. 184

- ^ "American Silent Feature Film Database: Manslaughter". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

External links

edit- Manslaughter at IMDb

- Manslaughter at the TCM Movie Database

- Manslaughter is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Manslaughter at Virtual History