Lots of Mommies is a 1983 picture book written by Jane Severance and illustrated by Jan Jones. In the story, Emily is raised by four women. Other children at her school doubt that she has "lots of mommies" but when she is injured, her four parents rush to her aid and her schoolmates accept that she does indeed have "lots of mommies".

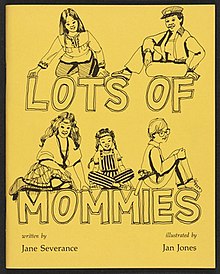

Cover art | |

| Author | Jane Severance |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Jan Jones |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's picture book |

| Publisher | Lollipop Power |

Publication date | 1983 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Paperback |

| Pages | 35 |

| ISBN | 0-914996-24-X |

The work was Severance's second to be published by Lollipop Power and her second picture book overall. Lots of Mommies has received praise in feminist news outlets since its publication and has attracted debate from children's literature scholars and others as to whether it should be considered a work of LGBTQ children's literature, absent explicit textual confirmation of Emily's mothers' relationships to one another. The work has also been noted for depicting a non-traditional family.

Background and publication

editThe first book by Jane Severance, a lesbian preschool teacher living in Denver, was When Megan Went Away, published by the Chapel Hill, North Carolina-based publisher Lollipop Power in 1979.[1][2] Severance, who penned When Megan Went Away when she was around 21 years old, was interested in writing works for families in her Denver lesbian community who "were raising children in collective households, but it was not as idyllic as the household shown in Lots of Mommies. It was a couple of really fucked up women with lots of kids from previous marriages and the mommies all drank."[3]

Lollipop Power, an independent press founded in 1970 with the goal of counteracting "sex-stereotyped behavior and role models presented by society to young children" published Lots of Mommies, Severance's second picture book, in 1983 as a 35-page paperback illustrated by Jan Jones in green and beige.[1][4][5] The book has been recommended for readers four to eight years old.[1]

Plot

editEmily lives with four women: her biological mother Jill, plus Annie Jo, Vicki, and Shadowoman. Annie Jo and Shadowoman drop Emily off at her new school for her first day. Emily decides to stand by a group of children who are discussing who dropped them off; when they ask her about her family, she replies that she has "lots of mommies". As the other children doubt and tease Emily, she walks away and climbs up the jungle gym.

While pretending to drive a school bus atop the playset, Emily falls and dislocates her arm. Various adults nearby all recognize Emily as the child of a different one of her caretakers and rush off in separate directions to find Emily's mothers. Jill, Annie Jo, Vicki, and Shadowoman all rush to Emily's aid at once and the other children realize that she does actually have "lots of mommies". One by one, her moms leave the schoolyard and Jill asks if she should stay with Emily, to which Emily replies that she is fine at school by herself and will tell her four mothers about her day when she gets home that evening.

Reception and legacy

editAlthough it received no reviews in major industry publications, Ann Martin-Leff in 1984 wrote in New Directions for Women that Lots of Mommies was a well illustrated and "warm and caring book".[1][5] Melody Ivins wrote in Feminist Bookstore News in 1990 that the work was "wonderfully diverse" and described it as one of just a few works available for the children of lesbians.[6] In 2012, the children's literature researcher Jamie Campbell Naidoo called Lots of Mommies groundbreaking and recommended the work.[1]

Some scholars and authors have disagreed about whether there is enough textual evidence to assert that Emily's parents are lesbians, and consequently whether Lots of Mommies should be construed as an LGBTQ picture book at all.[4] The researcher Virginia Wolf wrote that no evidence in the text of the work that "proves that any or all of the women are lesbians, although clearly their living arrangements raise the possibility."[7] Fellow LGBTQ children's author Lesléa Newman similarly stated that she believed "there's nothing explicit there that shows that any of them are lesbians. I mean they're living in a commune, and they have interesting names. But you know there's nothing that says that any of them are a couple."[8] Researcher Dianna Laurent wrote that the story does not address Emily's caregivers' relationships to one another and describes her parents as being a "communal women's group".[9]

Conversely, Naidoo described the book as "one of the first U.S. picture books to represent a non-traditional lesbian family".[1] The children's literature scholar Thomas Crisp has likewise written in favor of considering Lots of Mommies an LGBTQ picture book, stating "it is the semiotics that make the text queer".[10] According to Crisp, who concedes that none of the characters in the story identify as lesbians, the ambiguity surrounding the text stems from social attempts to normalize two-parent queer families "to offset anxiety about queer desire", leading to critical disavowal of Lots of Mommies and the family structure it depicts.[4]

Regardless of its contested status as a lesbian picture book, Lots of Mommies has also been noted for its depiction of a non-traditional (non-nuclear) family.[11] The English lecturer Jennifer Miller wrote that Lots of Mommies "shows a queer communal model of family" that, like the arrangement depicted in When Megan Went Away, "offer[s] an affirming alternative to the nuclear family."[12] As of the 2010s[update], the work was out of print and copies often sold for over 40 times the original retail price.[1][4]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Naidoo 2012, p. 145.

- ^ Crisp 2010, p. 93.

- ^ Crisp 2010, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c d Crisp 2010, p. 88.

- ^ a b Martin-Leff 1984, p. 18.

- ^ Ivins 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Wolf 1989, p. 53.

- ^ Peel 2015, p. 475.

- ^ Laurent 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Crisp 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Bunkers 1992, p. 119.

- ^ Miller 2022, p. 52.

Cited

edit- Bunkers, Suzanne (1992). "'We are not the Cleavers': Images of nontraditional families in children's literature". The Lion and the Unicorn. 16 (1): 115–133. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0110. S2CID 144554393.

- Crisp, Thomas (2010). "Setting the record 'straight': An interview with Jane Severance". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 35 (1): 87–96. doi:10.1353/chq.0.1950. S2CID 144164146.

- Ivins, Melody (September–October 1990). "Southern Sisters children's bibliography". Feminist Bookstore News. Vol. 13, no. 3. pp. 27–33. ISSN 0741-6555. JSTOR community.28036335.

- Laurent, Dianna (2009). "Children's literature, lesbian". In Nelson, Emmanuel S. (ed.). Encyclopedia of contemporary LGBTQ literature of the United States. ABC-CLIO. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9780313348600.

- Martin-Leff, Ann (January–February 1984). "For young readers". New Directions for Women. Vol. 13, no. 1. p. 18. ISSN 0160-1075. JSTOR community.28041145.

- Miller, Jennifer (2022). The Transformative Potential of LGBTQ+ Children's Picture Books. University Press of Mississippi. doi:10.14325/mississippi/9781496839992.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4968-4000-4.

- Naidoo, Jamie Campbell (2012). Rainbow family collections: Selecting and using children's books with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer content. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 9781598849608.

- Peel, Katie R. (2015). "An interview with Lesléa Newman: A punchy new Heather, Dolly Parton, and Orange is the New Black". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 19 (4): 470–483. doi:10.1080/10894160.2015.1057076. PMID 26264992. S2CID 6253368.

- Wolf, Virginia L. (1989). "The gay family in literature for young people". Children's Literature in Education. 20 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1007/BF01128040. S2CID 144389083.

External links

edit- Lots of Mommies at the Internet Archive