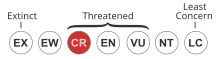

The longcomb sawfish, narrowsnout sawfish or green sawfish (Pristis zijsron) is a species of sawfish in the family Pristidae, found in tropical and subtropical waters of the Indo-West Pacific. It has declined drastically and is now considered a critically endangered species.[1][3][4][5]

| Longcomb sawfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Rhinopristiformes |

| Family: | Pristidae |

| Genus: | Pristis |

| Species: | P. zijsron

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pristis zijsron Bleeker, 1851

| |

Description

editThe longcomb sawfish is possibly the largest species of sawfish, reaching a total length of up to 7.3 m (24 ft), but rarely more than 6 m (20 ft) today.[1][4] Its upperparts are greenish-brown to olive, while the underparts are whitish.[4][6][7]

A combination of characters are necessary to distinguish it from the other sawfish species: the longcomb sawfish has teeth to near the base of the rostrum or "saw" (unlike the knifetooth sawfish, Anoxypristis cuspidata), 23–37 teeth on each side of the rostrum (18–24 in the dwarf sawfish, P. clavata, 20–32 in smalltooth sawfish, P. pectinata, and 14–24 in largetooth sawfish, P. pristis),[note 1] the teeth towards the tip of the rostrum are clearly closer to each other than those at its base (unlike the dwarf, smalltooth and largetooth sawfish where either equally spaced or only marginally closer to each other towards the tip of the rostrum), a relatively narrow rostrum, width equalling 9–17% of its length (typically wider in dwarf and largetooth sawfish), a rostrum that is 23–33% of the total length of the fish (20–25% in dwarf sawfish), relatively short pectoral fins (unlike the knifetooth and largetooth sawfish), a leading edge of the dorsal fin that is located clearly behind the leading edge of the pelvic fins (in front of in largetooth sawfish and roughly above in smalltooth sawfish) and it has a very small or no lower tail lobe (present in knifetooth and largetooth sawfish).[4][10] It can be further separated from the two most similar species, the dwarf and smalltooth sawfish, by the considerably smaller maximum size of the former species, and the less greenish colour (when alive/recently dead) and essentially Atlantic distribution of the latter species.[4][6] The smalltooth and longcomb sawfish might historically have come into contact in South Africa, but sawfish appear to have been extirpated from this country.[11][12]

Distribution and habitat

editThe longcomb sawfish is native to tropical and subtropical waters in the western and central Indo-Pacific. Historically its distribution covered almost 5,900,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) and it ranged from South Africa, north to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, east to the South China Sea, through Southeast Asia to Australia.[1][11] In Australia, it ranged from Shark Bay, along the northern part of the country, and south to Jervis Bay on the eastern coast.[5] Today it has disappeared from much of its historical range.[11] It can live in colder waters than its relatives, as also evidenced by the range in Australia where it occurs further south than the other species of sawfish.[4][13]

The longcomb sawfish is mainly found in coastal marine, mangrove and estuarine habitats, even in very shallow waters, but can also occur far offshore to a depth of more than 70 m (230 ft).[4][5] There are records from rivers far inland,[6] but it is not frequent in freshwater.[4][5] It is mainly found in places with a bottom consisting of sand, mud or silt.[5][6]

Behavior and life cycle

editThe longcomb sawfish feeds on fish, crustaceans and molluscs.[5] It thrashes its rostrum from side-to-side to dislodge prey from the seabed and to stun groups of fish.[6] All sawfish are harmless to humans, except when captured where they can cause serious injuries when defending themselves with their "saw".[6]

Little is known of its life cycle, but it is ovoviviparous and the young are 60–108 cm (24–43 in) long at birth.[6] It is often said that there are about 12 young in each litter,[1][4] but the basis for this number is unclear (in other sawfish species litter size ranges from 1 to 20).[11] The females give birth in inshore areas, and the young stay near the coast and in estuaries in the first part of their lives.[4][5] Sexual maturity is reached at an age of about 9 years,[5] and a length of 3.4–3.8 m (11–12 ft).[1] The maximum age is unknown, but it might be in excess of 50 years,[1] and an individual caught as a juvenile lived for 35 years at an aquarium.[5]

Conservation

editThe longcomb sawfish has declined drastically and is listed by the IUCN as "Critically Endangered" in its Red List of Threatened Species.[1] The fins (for shark fin soup) and saw (as novelty items) are highly valuable, while some parts are used in Asian traditional medicine and the meat is eaten. Fishing is the main threat, but it is also threatened by habitat loss.[1][5] Because of the potential threat they (or rather their "saw") represent to humans, they are sometimes killed before being brought onto the boat when accidentally caught.[5] Because of the "saw", all sawfish are particularly prone to becoming entangled in fishing nets.[1]

Historically the longcomb sawfish has been recorded in 37 countries, but it has been extirpated from 2 and possibly extirpated from another 24, leaving only 11 countries where it certainly still survives.[11] In terms of area this means that it certainly survives in only 62% of its historical range.[11] The total population is believed to have declined by more than 80% over three generations.[1] The subpopulations in Australia are among the few that remain viable, but even they have declined,[1] and the species no longer occurs in New South Wales.[14] It receives a level of protection in Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Qatar, South Africa (where already extirpated) and the United Arab Emirates,[11] but enforcement of fishing regulations are often lacking.[1] All sawfish species are listed on CITES Appendix I, which restricts international trade.[1]

Longcomb sawfish have few natural enemies, but can fall prey to large sharks and crocodiles.[6]

Small numbers are kept in public aquariums, with studbooks listing 13 individuals (7 males, 6 females) in North America in 2014, 6 individuals (3 males, 3 females) in Europe in 2013, and 2 individuals in Japan in 2017.[13]

Threats

editThe longcomb sawfish faces significant threats attributed to intense and poorly managed fishing pressure throughout its range. This pressure arises from both commercial and small-scale fisheries, including artisanal, cultural, and subsistence practices. Various fishing gears such as gillnets, trawls, and lines are utilized, with the distinctive toothed rostra of sawfish making them particularly vulnerable to entanglement, especially in gillnets and trawls. Over recent decades, fishing effort has escalated across the species' range, driven by escalating demand and exploitation in the fin and meat trade.[1]

The longcomb sawfish encounters high fishing pressure, resulting in poorly regulated and unmanaged exploitation. Bycatch in both commercial and small-scale fisheries, driven by escalating demand for fins and meat, poses a considerable threat. The species is frequently retained for these valuable parts, contributing to population decline. In some regions, measures such as the release of sawfishes by fishers may still lead to significant at-vessel and post-capture mortality, further impacting population viability.[1]

Critical habitats of the longcomb sawfish, including inshore freshwater, estuarine, mangrove, and coastal areas, are under threat due to habitat loss and degradation. The reduction of mangrove areas in Southeast Asia, for instance, is estimated to be around 30% since 1980. The most affected habitats are those crucial for nearshore and estuarine nursery activities. Additionally, potential impacts on adult longcomb sawfish associated with offshore oil and gas extraction, including activities like seismic surveys, further compound habitat threats in various regions.[1]

Historically, the northwest region of Australia provided relatively undisturbed coastal habitats for the longcomb sawfish. Presently, various factors pose substantial threats to the species in Western Australia, including coastal developments such as mining, natural resource operations, and oil and gas extraction. These developments introduce structures like lighted jetties, dredged shipping channels, and offloading structures, potentially hindering the movement of juvenile longcomb sawfish along the coastline. The increased prevalence of these structures may lead to population fragmentation or the destruction of vital juvenile habitats for the species.[1]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Harry, A.V.; Everett, B.; Faria, V.; Fordham, S.; Grant, M.I.; Haque, A.B.; Ho, H.; Jabado, R.W.; Jones, G.C.A.; Lear, K.O.; Morgan, D.L.; Philips, N.M.; Spaet, J.L.Y.; Tanna, A.; Wueringer, B.E. (2022). "Pristis zijsron". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T39393A58304631. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T39393A58304631.en. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Pristis zijsron". FishBase. November 2017 version.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Last; White; de Carvalho; Séret; Stehmann & Naylor (2016). Rays of the World. CSIRO. pp. 59–66. ISBN 9780643109148.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Department of the Environment (2017). "Pristis zijsron — Green Sawfish, Dindagubba, Narrowsnout Sawfish". Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Seitz, J.C. "Green sawfish". Ichthyology. Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Allen, G. (1999). Marine Fishes of Tropical Australia and South East Asia (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-7309-8363-3.

- ^ Slaughter, Bob H.; Springer, Stewart (1968). "Replacement of Rostral Teeth in Sawfishes and Sawsharks". Copeia. 1968 (3): 499–506. doi:10.2307/1442018. JSTOR 1442018.

- ^ Wueringer, B.E.; L. Squire Jr. & S.P. Collin (2009). "The biology of extinct and extant sawfish (Batoidea: Sclerorhynchidae and Pristidae)". Rev Fish Biol Fisheries. 19 (4): 445–464. Bibcode:2009RFBF...19..445W. doi:10.1007/s11160-009-9112-7. S2CID 3352391.

- ^ Whitty, J. & N. Phillips. "Pristis zijsron (Bleeker, 1851)". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dulvy; Davidson; Kyne; Simpfendorfer; Harrison; Carlson & Fordham (2014). "Ghosts of the coast: global extinction risk and conservation of sawfishes" (PDF). Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 26 (1): 134–153. doi:10.1002/aqc.2525.

- ^ Everett; Cliff; Dudley; Wintner & van der Elst (2015). "Do sawfish Pristis spp. represent South Africa's first local extirpation of marine elasmobranchs in the modern era?". African Journal of Marine Science. 37 (2): 275–284. Bibcode:2015AfJMS..37..275E. doi:10.2989/1814232X.2015.1027269. S2CID 83912626.

- ^ a b White, S. & K. Duke (2017). Smith; Warmolts; Thoney; Hueter; Murray & Ezcurra (eds.). Husbandry of sawfishes. Special Publication of the Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 75–85. ISBN 978-0-86727-166-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Phillips, N. & Wueringer, B. (Autumn 2015). "Sawfish. Ancient predators in need of modern conservation tools". Wildlife Australia. Vol. 52, no. 1. pp. 14–17. ISSN 0043-5481.