London, the capital of England and the United Kingdom, has a fiscal surplus since the tax collected is above the amount spent on local services. Of all the United Kingdom's statistical regions, London runs the highest surplus, both in absolute terms and per capita. In the 2016–17 fiscal year, London's surplus was £32.5 billion and its fiscal transfer was £38.6 billion.

History

editThe Labour Party manifesto for the 1964 United Kingdom general election mentions "drift to the south" and the imbalance of London's economy compared to other parts of the United Kingdom as problems to be addressed by the central government. The Labour Party won the election, and Harold Wilson's government made a requirement that all new government organisations be set up outside London to combat excessive centralization. However, the imbalance continued to increase.[1]

The London surplus averaged £15 billion between 2000 and 2009,[2] around 4 to 9 per cent of the region's gross value added. During the Great Recession, the surplus was reduced to less than three per cent of GVA.[3] The surplus increased by £11 billion between 2015–16 and 2017–18.[1]

Surplus

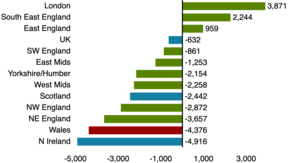

editIn the 2016–17 fiscal year, London's fiscal surplus was £32.5 billion and its fiscal transfer was £38.6 billion after accounting for its share of UK-wide debt. This is similar to the England-wide fiscal transfer of £29.7 billion.[4] Only three UK statistical regions run a surplus, the others being South East England and East of England, whose surpluses are smaller than London's.[5][6] In 2016–17, the surplus was £3,698 per person.[7]

Around 2014, London contributed about one-quarter of UK income tax and corporation tax revenue.[2] Tax revenue per capita in London is nearly double that in Wales and North East England.[8]

Implications

editThe surplus mostly goes to funding expenditure in less wealthy parts of the United Kingdom, such as northern England.[2][7] Reducing the North–South divide via government intervention is popular among both left-wing populists and parts of the Conservative Party.[9] In 2019, leading candidates in the upcoming London mayoral election signed a letter expressing support for greater fiscal autonomy for London and other parts of the UK.[10] According to Financial Times, "Government spending in London is more focused on factors that create long term growth", with more spending on transportation and scientific research than other regions.[7] London spends less on social welfare than other parts of the UK.[2]

The Times economics editor David Smith suggested that "London bankrolls the UK – and that’s not healthy".[11] Smith also wrote that "The challenge is to spread the success of one economically and fiscally successful part of the country, London and the southeast, without damaging it. It is a challenge with no easy solutions, as successive governments have found".[11][1] Jack Brown, a researcher for Centre for London, claimed that "the nation would fold" without London tax revenue. He advocated decentralization which he saw as beneficial both for London and other areas.[12]

According to a 2019, YouGov survey, 60% of British people think that London "gets more than its fair share of public spending", but only 20% of London residents agree.[12][13]

References

edit- ^ a b c Hill, Dave (4 June 2019). "London's tax support for the wider UK has risen again. What should be done?". OnLondon. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Greg (2014). The Making of a World City: London 1991 to 2021. John Wiley & Sons. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-118-60972-9.

- ^ McCann, Philip (2016). The UK Regional-National Economic Problem: Geography, globalisation and governance. Routledge. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-317-23718-1.

- ^ "Fiscal Transfers". Scotfact. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Rutter, Calum (2 August 2019). "Welsh spending cuts cause deficit reduction, says study". Public Finance. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Which parts of the UK have the most money spent on them?". BBC News. 13 January 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Gavin (1 August 2018). "London's fiscal surplus drifts further away from rest of UK — ONS". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Elliott, Larry (23 May 2017). "London economy subsidises rest of UK, ONS figures show". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Hill, Dave (30 January 2019). "Would penalising London help close the 'north-south divide'?". OnLondon. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Hill, Dave (26 November 2019). "Sadiq Khan and mayoral rivals join plea for devolution boost". OnLondon. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, David (2 June 2019). "London bankrolls the UK – and that's not healthy". The Times. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b Brown, Jack (20 May 2019). "London is still the UK's golden goose – and that needs to change". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Smith, Matthew (7 February 2019). "London gets more than its fair share of public spending, say most Britons". YouGov. Retrieved 29 April 2020.