The Constitution of the United States gives Congress the authority to remove the president of the United States from office in two separate proceedings. The first one takes place in the House of Representatives, which impeaches the president by approving articles of impeachment through a simple majority vote. The second proceeding, the impeachment trial, takes place in the Senate. There, conviction on any of the articles requires a two-thirds majority vote and would result in the removal from office (if currently sitting), and possible debarment from holding future office.[1]

Many U.S. presidents have been subject to demands for impeachment by groups and individuals.[2][3][4][5][6] Three presidents have been impeached, although none were convicted: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump twice, in 2019 and 2021. Additionally, impeachment proceedings were commenced against two other presidents, John Tyler, in 1843, and Richard Nixon, in 1974, for his role in the Watergate scandal, but he resigned from office after the House Judiciary Committee adopted three articles of impeachment against him (1. obstruction of justice, 2. abuse of power, and 3. contempt of Congress), but before the House could vote on either article.

Impeachments

Andrew Johnson

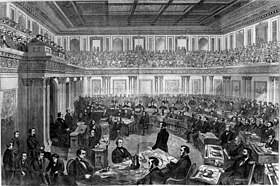

President Andrew Johnson held open disagreements with Congress, who tried to remove him several times. The Tenure of Office Act was enacted over Johnson's veto to curb his power and he openly violated it in early 1868.[7]

The House of Representatives adopted 11 articles of impeachment against Johnson.[8]

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presided over Johnson's Senate trial. Conviction failed by one vote in May 1868. The impeachment trial remained a unique event for 130 years.[9]

Bill Clinton

On October 8, 1998, the House of Representatives voted to launch an impeachment inquiry into President Bill Clinton, in part because of allegations that he lied under oath when being investigated in the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal.[10]

On December 19, 1998, two articles of impeachment were approved by the House, charging Clinton with perjury and obstruction of justice.[11] The charges stemmed from a sexual harassment lawsuit filed against Clinton by Arkansas state employee Paula Jones and from Clinton's testimony denying that he had engaged in a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.[citation needed] They were:

Article I, charged Clinton with perjury.[12][13] Article II, charged Clinton with obstruction of justice.[12][14]

Chief Justice William Rehnquist presided over Clinton's Senate trial. Both articles of impeachment failed to receive the required super-majority, and so Clinton was acquitted and was not removed from office.[15]

Donald Trump

First impeachment

After a whistleblower accused President Donald Trump of pressuring a foreign government to interfere on Trump's behalf prior to the 2020 election, the House initiated an impeachment inquiry.[16][17] On December 10, 2019, the Judiciary Committee approved two articles of impeachment (H.Res. 755): abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.[18] On December 18, 2019, the House voted to impeach Trump on two charges:[19]

- Abuse of power by "pressuring Ukraine to investigate his political rivals ahead of the 2020 election while withholding a White House meeting and $400 million in U.S. security aid from Kyiv."[20]

- Obstruction of Congress by directing defiance of subpoenas issued by the House and ordering officials to refuse to testify.[20]

On January 31, 2020, the Senate voted 51–49 against calling witnesses or issuing subpoenas for any additional documents.[21] On February 5, 2020, the Senate found Trump not guilty of abuse of power, by a vote of 48–52, with Republican senator Mitt Romney being the only senator—and the first senator in U.S. history—to cross party lines by voting to convict,[22][23] and not guilty of obstruction of Congress, by a vote of 47–53.[22][23]

Chief Justice John Roberts presided over Trump's first trial. As both articles of impeachment failed to receive the required super-majority, Trump was acquitted and was not removed from office.[23]

Second impeachment

Trump was impeached for a second time after he was alleged to incite a deadly attack on the United States Capitol by attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election results after his loss to Joe Biden.[24][25][26][27] On January 13, 2021, the House voted to impeach Trump for "Incitement of Insurrection".

Although Trump's term ended on January 20, the trial in the Senate began on February 9.[28] On February 13, the Senate found Trump not guilty of incitement of insurrection, by a vote of 57 for conviction and 43 against, below the 67 votes needed for a supermajority.[29] In previous impeachment proceedings, only one senator had ever voted to convict a president of their own party. This time, seven Republican senators found Trump guilty, making it the most bipartisan impeachment trial.

As Trump was no longer president, the president pro tempore of the Senate Patrick Leahy presided over Trump's second trial. As the article of impeachment failed to receive the required supermajority, Trump was acquitted.

Table of impeachment trial results

| Vote | Guilty | Not guilty | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson[30] | Article II | 35 | 64.82% | 19 | 35.19% | Acquittal |

| Article III | 35 | 64.82% | 19 | 35.19% | Acquittal | |

| Article XI | 35 | 64.82% | 19 | 35.19% | Acquittal | |

| Articles I, IV, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X | no vote held | Acquittal | ||||

| Impeachment trial of Bill Clinton | Article I[31] | 45 | 45% | 55 | 55% | Acquittal |

| Article II[32] | 50 | 50% | 50 | 50% | Acquittal | |

| First impeachment trial of Donald Trump[33][34] | Article I | 48 | 48% | 52 | 52% | Acquittal |

| Article II | 47 | 47% | 53 | 53% | Acquittal | |

| Second impeachment trial of Donald Trump[35] | 57 | 57% | 43 | 43% | Acquittal | |

Resignation during an impeachment process

Richard Nixon

The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment against President Richard Nixon for obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress for his role in the Watergate scandal.[36]

On October 20, 1973, Nixon ordered the firing of Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, precipitating the Saturday Night Massacre. A massive reaction took place, especially in Congress, where 17 resolutions were introduced between November 1, 1973, and January 1974: H.Res. 625, H.Res. 635, H.Res. 643, H.Res. 648, H.Res. 649, H.Res. 650, H.Res. 652, H.Res. 661, H.Res. 666, H.Res. 686, H.Res. 692, H.Res. 703, H.Res. 513, H.Res. 631, H.Res. 638, and H.Res. 662.[37][38] H.Res. 803, passed February 6, authorized a Judiciary Committee investigation,[39] and in July, that committee approved three articles of impeachment. Before the House took action, the impeachment proceedings against Nixon were mooted when Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. A report containing articles of impeachment was accepted by the full House on August 20, 1974, by a vote of 412–3.[40]

Although Nixon was never formally impeached, this is the only impeachment attempt to result in the president resigning from office. In September 1974, his successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned Nixon for any crimes against the United States that he might have committed while president.

Investigations without impeachment

James Buchanan

In 1860, the House of Representatives set up the United States House Select Committee to Investigate Alleged Corruptions in Government, known as the Covode Committee after its chairman, Rep. John Covode (R-PA), to investigate President James Buchanan on suspicion of bribery and other allegations. After about a year of hearings, the committee concluded that Buchanan's actions did not merit impeachment.[41]

Andrew Johnson

On January 7, 1867, the House of Representatives voted to approve an impeachment inquiry run by the House Committee on the Judiciary, which initially ended in a June 3, 1867 vote by the committee to recommend against forwarding articles of impeachment to the full House.[42] However, on November 25, 1867, the House Committee on the Judiciary, which had not previously forwarded the result of its inquiry to the full House, reversed their previous decision, and voted in a 5–4 vote to recommend impeachment proceedings, however, the full House rejected this recommendation by a 108–56 vote.[43][44][45] Johnson would later, separately, be impeached in 1868.

Joe Biden (ongoing)

On January 21, 2021, the day after the inauguration of Joe Biden, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) filed articles of impeachment against President Biden. She cited abusing his power while serving as vice president. Her articles of impeachment claimed that Viktor Shokin was investigating the founder of Burisma Holdings, a natural gas giant in Ukraine. Biden's son Hunter Biden had served as a member of the board since 2014.[46] However, Shokin was not investigating the company. There is no concrete evidence that suggests Biden had pressured Ukraine to benefit his son.[47]

In June 2021, Donald Trump expressed interest in running for a House of Representatives seat in Florida in the 2022 midterm elections, getting himself elected Speaker of the House, and then beginning an impeachment inquiry into President Biden.[48]

Following the withdrawal of American military forces from Afghanistan, the Fall of Kabul on August 15, 2021, and the subsequent attack on Kabul's airport, several Republicans, including Representative Greene, Lauren Boebert, Ronny Jackson, and especially Senators Rick Scott and Lindsey Graham, called for either the stripping of powers and duties (via the 25th Amendment) or removal from office (via impeachment) of Joe Biden if Americans and allies were left behind and held hostage in Afghanistan by the Taliban.[49][50] House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy pledged a “day of reckoning” against Biden.[51] Some Republicans, including Josh Hawley and Marsha Blackburn, called for Vice President Kamala Harris and Biden's other Cabinet officials to be removed as well.[52][better source needed] Mitch McConnell did not call for an impeachment inquiry into Biden, however, as Republicans do not have the majority in either the house or senate.[53]

In January 2022, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) predicted that if Republicans won control of the U.S. House of Representatives in the 2022 United States House of Representatives elections, they would likely move to impeach Biden "whether it's justified or not".[54] In August The Hill reported that impeaching Biden was "a top priority" for House Republicans, should they win control of that body in the 2022 mid-term elections,[55] as they eventually did.

In June 2023, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to pass a rule that referred an impeachment resolution against President Joe Biden to a committee. The resolution was offered by Republican Representative Lauren Boebert of Colorado. The referral to the committee effectively paused a move to bring a privileged motion to the floor, which would have required members of the House to vote on whether to impeach President Biden. The resolution was met with division among House Republicans, and Speaker Kevin McCarthy urged members of the GOP to vote against it. Boebert stated that she pushed for the vote to force her colleagues to make difficult decisions.[56]

Speaker Kevin McCarthy in September 2023 directed three House committees to open a formal impeachment inquiry.[57] In December, under the leadership of Speaker Mike Johnson, the whole House voted 221-213 to formally initiate an impeachment inquiry.[58] The committees — Oversight, Judiciary, and Ways and Means — jointly reported findings in August 2024 that alleged several impeachable offenses and withholding of evidence.[59]

Inquiries voted down by the full House

Thomas Jefferson

On January 25, 1809, Rep. Josiah Quincy III (a Federalist from Massachusetts) introduced resolutions which would launch an impeachment inquiry into President Thomas Jefferson, by then a lame duck who was scheduled to leave office on March 4, 1809. Quincy alleged that Jefferson had committed a "high misdemeanor" by keeping Benjamin Lincoln, the Port of Boston's customs collector, in that federal office despite Lincoln's own protests that he was too old and too weak to continue with his job. In 1806, Lincoln had written Jefferson proposing his own resignation, but Jefferson requested that Lincoln continue in the office until he appointed a successor. Quincy argued that, by leaving Lincoln in the post, Jefferson had unfairly enabled a federal official to receive a $5,000 annual salary, "for doing no services".[60]

The resolution received immediate resistance from both Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, and saw 17 members of the House speak against even providing consideration of the resolution.[60] Quincy refused to withdraw his resolution, despite the immense opposition.[60] Congressmen argued that the act of requesting Lincoln remain in office was not a high crime nor a misdemeanor, and that there was not even evidence of inefficient management of the customs house.[60] The House voted 93–24 to allow consideration of the resolution.[61] After consideration, it was rejected by a vote of 117–1, with Quincy being the sole supporter.[60][61]

John Tyler

After President John Tyler vetoed a tariff bill in June 1842, a committee headed by former president John Quincy Adams, then a representative, condemned Tyler's use of the veto and stated that Tyler should be impeached.[62] (This was not only a matter of the Whigs supporting the bank and tariff legislation which Tyler vetoed. Until the presidency of the Whigs' archenemy Andrew Jackson, presidents vetoed bills rarely, and then generally on constitutional rather than policy grounds,[63] so Tyler's actions also went against the Whigs' concept of the presidency.) In August, the House accepted this report, which implied that impeachable offenses had been committed by Tyler, in a vote of 100–80.[64]

Tyler criticized the House for, what he argued, was a vote effectively charging him with impeachable offenses without actually impeaching him of such offenses, thus denying him the ability to defend himself against these charges in a Senate trial.[64]

Rep. John Botts (Whig-VA), who opposed President Tyler (who was a member of the same party Tyler had up until recently been a member of), introduced an impeachment resolution on July 10, 1842, that levied several charges against Tyler regarding his use of the presidential veto power and called for a nine-member committee to investigate his actions, with the expectation of a formal impeachment recommendation.[65][66] The impeachment resolution was defeated in a 127–83 vote on January 10, 1843.[66][67][68]

Inquiries proposed but not put to a House vote

Ulysses S. Grant

Rep. Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn (D-KY) introduced an impeachment resolution against President Ulysses S. Grant in 1876, regarding the number of days Grant had been absent from the White House. The resolution never gained momentum and was tabled in December 1876.[69]

Grover Cleveland

Rep. Milford W. Howard (Populist-AL), on May 23, 1896, submitted a resolution (H.Res 374) impeaching President Grover Cleveland for selling unauthorized federal bonds and breaking the Pullman Strike. It was neither voted on nor referred to a committee.[70]

Herbert Hoover

During the 1932–33 lame duck session of Congress, on December 13, 1932, and on January 17, 1933, Rep. Louis Thomas McFadden (R-PA) introduced two impeachment resolutions against President Herbert Hoover, over economic grievances. The resolutions were read and then immediately tabled by overwhelming votes.[70][71]

Harry S. Truman

In April 1951, President Harry S. Truman fired General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Congressional Republicans responded with numerous calls for Truman's removal. The Senate held hearings, and a year later, Representatives George H. Bender and Paul W. Shafer separately introduced House bills 607 and 614 against President Truman. The resolutions were referred to the Judiciary Committee[72] but were not considered by the Democratic-held Senate.

On April 22, 1952, Rep. Noah M. Mason (R-IL) suggested that impeachment proceedings should be started against President Harry S. Truman for seizing the nation's steel mills. Soon after Mason's remarks, Rep. Robert Hale (R-ME) introduced a resolution (H.Res. 604).[73][74] After three days of debate on the floor of the House, it was referred to the House Judiciary Committee, but no action was taken.[70]

Ronald Reagan

In 1983, Representative Henry B. González was joined by Ted Weiss, John Conyers Jr., George Crockett Jr., Julian C. Dixon, Mervyn M. Dymally, Gus Savage and Parren J. Mitchell in proposing a resolution impeaching Reagan for "the high crime or misdemeanor of ordering the invasion of Grenada in violation of the Constitution of the United States, and other high crime or misdemeanor ancillary thereto."[75]

On March 5, 1987, Rep. González (D-TX) introduced H.Res. 111, with six articles against President Ronald Reagan regarding the Iran-Contra affair to the House Judiciary Committee, where no further action was taken. While no further action was taken on this particular bill, it led directly to the joint hearings of the subject that dominated the news later that year.[70][75][76][77] After the hearings were over, USA Today reported that articles of impeachment were discussed but decided against.

Edwin Meese acknowledged, in testimony at the trial of Reagan aide Oliver North, that officials in the Reagan administration had been worried that the 1987 impeachment could result in Reagan having to resign.[78]

George H. W. Bush

President George H. W. Bush[79] was subject to two resolutions over the Gulf War in 1991, both by Rep. Henry B. González (D-TX).[70][37] H.Res. 34 was introduced on January 16, 1991, and was referred to the House Committee on Judiciary and then its Subcommittee on Economic and Commercial Law on March 18, 1992.[80][81] H.Res. 86 was introduced on February 21, 1991, and referred to the House Judiciary Committee, where no further action was taken on it.[82]

George W. Bush

During the administration of President George W. Bush, several American politicians sought to either investigate him for possible impeachable offenses or to bring actual impeachment charges. The most significant of these occurred on June 10, 2008, when Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-OH) and Rep. Robert Wexler (D-FL) introduced H.Res. 1258, containing 35 articles of impeachment[83] against Bush.[84] After nearly a day of debate, the House voted 251–166 to refer the impeachment resolution to the House Judiciary Committee on June 11, 2008, where no further action was taken on it.[85]

Others

Lyndon B. Johnson

On May 3, 1968, a petition to impeach President Lyndon B. Johnson for "military and political duplicity" was referred to the House Judiciary Committee.[86] No action was taken.[citation needed]

Barack Obama

On December 3, 2013, the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on President Barack Obama that was formally titled "The President's Constitutional Duty to Faithfully Execute the Laws," which political journalists viewed as an attempt to begin justifying impeachment proceedings. When asked by reporters if this was a hearing about impeachment, Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX) claimed that it was not, saying "I didn't mention impeachment nor did any of the witnesses in response to my questions at the Judiciary Committee hearing."[87][88][89] One witness did mention impeachment directly: Georgetown University law professor Nicholas Quinn Rosenkranz said "a check on executive lawlessness is impeachment" as he accused Obama of "claim[ing] the right of the king to essentially stand above the law." Impeachment efforts never advanced past this, making Obama the first president since Jimmy Carter to not have a single article of impeachment referred against him to the House Judiciary Committee during his tenure.[90]

See also

References

- ^ Cole, J. P.; Garvey, T. (October 29, 2015). "Report No. R44260, Impeachment and Removal" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2016. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Tentative Description of a Dinner Given to Promote the Impeachment of President Eisenhower". www.citylights.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Epstein, Jennifer (March 21, 2011). "Kucinich: Libya action 'impeachable'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ "Censured but not impeached". Miller Center. October 3, 2019. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "Impeaching James K. Polk | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org. May 24, 2006. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "Impeachment: Andrew Johnson". The History Place. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ "98-763 GOV Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). digital.library.unt.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ "President Clinton impeached". HISTORY. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ "President Clinton impeached". history.com. A&E Television Networks. January 13, 2021 [November 24, 2009]. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ landmarkcases.dcwdbeta.com, Landmark Supreme Court Cases (555) 123-4567. "Landmark Supreme Court Cases | Articles of Impeachment against President Clinton, 1998". Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b This article incorporates public domain material from A History of the Committee on the Judiciary 1813–2006, Section II–Jurisdictions History of the Judiciary Committee: Impeachment (PDF). United States House of Representatives. Retrieved December 23, 2019. (H. Doc. 109-153).

- ^ Text of Article I Archived December 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post December 20, 1998.

- ^ Text of Article IIII Archived December 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post December 20, 1998.

- ^ Baker, Peter; Dewar, Helen (February 13, 1999). "The Senate Acquits President Clinton". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ Przybyla, Heidi; Edelman, Adam (September 24, 2019). "Nancy Pelosi announces formal impeachment inquiry of Trump". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael S.; Barnes, Julian E.; Haberman, Maggie (November 26, 2019). "Trump Knew of Whistle-Blower Complaint When He Released Aid to Ukraine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 29, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ "Read the Articles of Impeachment against President Trump". The New York Times. December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ Shear, Michael D.; Baker, Peter (December 19, 2019). "Trump Impeachment Vote Live Updates: House Votes to Impeach Trump for Abuse of Power". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Herb, Jeremy; Raju, Manu (December 19, 2019). "House of Representatives impeaches President Donald Trump". CNN. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ "Senate Rejects Witnesses in Trump Impeachment Trial". Wall Street Journal. January 31, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Fandos, Nicholas (February 5, 2020). "Trump Acquitted of Two Impeachment Charges in Near Party-Line Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c "How senators voted on Trump's impeachment". Politico. February 7, 2020. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Ilhan Omar drawing up impeachment articles as seven Dems call for Trump's removal". The Independent. January 6, 2021. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Jon. "New York congressional members say they're safe; Some call for Trump's impeachment". Democrat and Chronicle.

- ^ "James Clyburn calls impeaching Trump again a waste of time, but says he's open to DOJ charges". www.cbsnews.com. January 5, 2021. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "R.I. delegation decries 'outrageous' attack by Trump supporters on US Capitol - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Trump's Senate impeachment trial to begin in two weeks". January 22, 2021. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Senate acquits Trump of inciting deadly Capitol attack". Politico. February 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (1868) President of the United States". www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress - 1st Session". www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Archived from the original on February 23, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress - 1st Session". www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 116th Congress, Second Session (PDF) (Report). Vol. 166. United States Government Publishing Office. February 5, 2020. pp. S937 – S938. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ Fandos, Nicholas (February 5, 2020). "Trump Acquitted of Two Impeachment Charges in Near Party-Line Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Donald Trump impeachment trial: Ex-president acquitted of inciting insurrection". BBC News. February 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Cai, Weiyi (December 18, 2019). "What is the impeachment process? A step by step guide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ a b "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview". everycrsreport.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "The History Place - Impeachment: Richard Nixon". www.historyplace.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ "H.Res.803 - 93rd Congress (1973-1974): Resolution providing appropriate power to the Committee on the Judiciary to conduct an investigation of whether sufficient grounds exist to impeach Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States". www.congress.gov. February 6, 1974. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "The Nixon Impeachment Proceedings". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ Zeitz, Joshua (December 18, 2019). "What Democrats Can Learn From the Forgotten Impeachment of James Buchanan". POLITICO. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ "Building the Case for Impeachment, December 1866 to June 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment Efforts Against President Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment Rejected, November to December 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Case for Impeachment, December 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Marcos, Christina (January 21, 2021). "Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene files articles of impeachment against Biden". The Hill. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Haltiwanger, John. "A Ukraine gas company tied to Joe Biden's son is at the center of Trump's impeachment". Business Insider. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ "Trump suggests he may run for House in 2022 to become speaker: "very interesting"". Newsweek. June 4, 2021. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris (August 17, 2021). "Analysis: Rick Scott just went there on Joe Biden and the 25th Amendment". CNN. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Relman, Eliza. "Lindsey Graham threatens Biden with impeachment if US troops don't stay in Afghanistan past August and 'accept the risk' of Taliban attacks". Business Insider. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "McCarthy promises 'day of reckoning' on Afghanistan in response to Biden impeachment calls". news.yahoo.com. August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Solender, Andrew. "GOP Lawmakers Ramp Up Calls For Biden's Resignation, Removal Over Kabul Attacks". Forbes. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Metzger, Bryan. "McConnell shoots down question of Biden being impeached, says the idea is a non-starter since Democrats control Congress". Business Insider. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ Sonmez, Felicia (January 4, 2022). "Sen. Ted Cruz says Republicans are likely to impeach Biden if they retake House". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Lillis, Mike (August 30, 2022). "House conservatives prep plans to impeach Biden". The Hill.

- ^ Grayer, Kristin Wilson,Haley Talbot,Annie (June 22, 2023). "House votes to refer Biden impeachment resolution to committee | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haley Talbot; Lauren Fox; Melanie Zanona (September 12, 2023). "McCarthy calls for formal impeachment inquiry into Biden". CNN.

- ^ "House approves impeachment inquiry into President Biden as Republicans rally behind investigation". Associated Press News. December 13, 2023.

- ^ Kaplan, Rebecca; Nobles, Ryan; Grumbach, Gary; Fitzpatrick, Sarah; Tsirkin, Julie (August 19, 2024). "GOP-led House committees release lengthy report alleging President Biden committed impeachable offenses". NBC News. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Fagal, Andrew J. B. "Perspective | This is not the first Congress to debate impeaching a lame-duck president". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Banning, Lance (February 2021). "Attempted Impeachment of Thomas Jefferson". American Heritage. 66 (22). Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Graff, Henry Franklin, ed. (1996). The Presidents: A Reference History. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-684-80471-2. (essay by Richard P. McCormick)

- ^ Graff (1996), p. 115 (essay by Richard B. Latner)

- ^ a b Holt, Michael F. (February 2021). "Attempts to Impeach John Tyler". American Heritage. 66 (2). Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Lucas, Fred (December 22, 2019). "A Lesson for Trump? When Impeaching A President Doesn't Go As Planned". nationalinterest.org. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Shafer, Ronald G. (September 23, 2019). "'He lies like a dog': The first effort to impeach a president was led by his own party". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 27, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment Grounds: Part 5: Selected Douglas/Nixon Inquiry Materials". everycrsreport.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Maness, Lonnie E.; Chesteen, Richard D. (1980). "The First Attempt at Presidential Impeachment: Partisan Politics and Intra-Party Conflict at Loose". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 10 (1): 51–62. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27547533. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "'Why We Laugh' Pro Tem". Harper's Weekly. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Baker, Peter (November 30, 2019). "Long Before Trump, Impeachment Loomed Over Multiple Presidents". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ Howard, Spencer (October 30, 2019). "The Impeachment of Herbert Hoover – Hoover Heads". hoover.blogs.archives.gov/. Herbert Hoover Library and Museum (National Archives). Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ 98 Cong. Rec. 4325, 4518 (1952)

- ^ "H.Res. 604". 82nd Congress 2nd Session.

- ^ "Seizure of Steel Mills". Remarks in the: House, Congressional Record. 98: 4222–4240. April 22, 1952.

- ^ a b John Nichols (2016). "The Genius of Impeachment: The Founders' Cure for Royalism". The New Press. ISBN 9781595587350. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Texan Acts for Impeachment". The New York Times. Washington DC. March 6, 1987. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Doyle McManus (June 15, 1987). "Reagan Impeachment Held Possible: It's Likely if He Knew of Profits Diversion, Hamilton Says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ David Johnston (March 29, 1989). "Meese Testifies That Impeachment Was a Worry". The New York Times. Washington DC. p. 17. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Meacham, Jon (November 12, 2015). "The Hidden Hard-line Side of George H.W. Bush". POLITICO Magazine.

- ^ "H.Res.34 - Impeaching George Herbert Walker Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". congress.gov. March 18, 1992. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ 137 Cong. Rec. 1736 (1991).

- ^ "H.Res.86 - Impeaching George Herbert Walker Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". congress.gov. February 21, 1991. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ "H. Res. 1258, 110th Cong". 2008. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Man, Anthony (June 10, 2008). "Impeach Bush, Wexler says". South Florida Sun-Sentinel.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ^ Kucinich, Dennis J. (June 11, 2008). "Actions - H.Res.1258 - 110th Congress (2007-2008): Impeaching George W. Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". www.congress.gov. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ "Johnson Impeachment Asked". The New York Times.

- ^ "Enough with impeachment blatherings". San Antonio Express-News. December 6, 2013. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ Milbank, Dana (December 3, 2013). "Republicans see one remedy for Obama — impeachment". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ James, Frank (August 27, 2013). "Impeach Obama! (And FDR, Eisenhower, Carter, Reagan, Etc.)". NPR.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ "Dana Milbank: The GOP's impeachment fever". SentinelAndEnterprise.com. December 9, 2013. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

Further reading

- Jon Meacham; Timothy Naftali; Peter Baker; Jeffrey A. Engel (2018). Impeachment: An American History. Modern Library. ISBN 978-1984853783.