A mechanical linkage is an assembly of systems connected so as to manage forces and movement. The movement of a body, or link, is studied using geometry so the link is considered to be rigid.[1] The connections between links are modeled as providing ideal movement, pure rotation or sliding for example, and are called joints. A linkage modeled as a network of rigid links and ideal joints is called a kinematic chain.

Linkages may be constructed from open chains, closed chains, or a combination of open and closed chains. Each link in a chain is connected by a joint to one or more other links. Thus, a kinematic chain can be modeled as a graph in which the links are paths and the joints are vertices, which is called a linkage graph.

The movement of an ideal joint is generally associated with a subgroup of the group of Euclidean displacements. The number of parameters in the subgroup is called the degrees of freedom (DOF) of the joint. Mechanical linkages are usually designed to transform a given input force and movement into a desired output force and movement. The ratio of the output force to the input force is known as the mechanical advantage of the linkage, while the ratio of the input speed to the output speed is known as the speed ratio. The speed ratio and mechanical advantage are defined so they yield the same number in an ideal linkage.

A kinematic chain, in which one link is fixed or stationary, is called a mechanism,[2] and a linkage designed to be stationary is called a structure.

History

editArchimedes[3] applied geometry to the study of the lever. Into the 1500s the work of Archimedes and Hero of Alexandria were the primary sources of machine theory. It was Leonardo da Vinci who brought an inventive energy to machines and mechanism.[4]

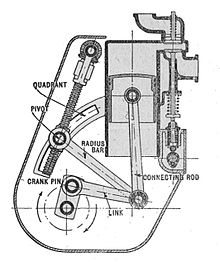

In the mid-1700s the steam engine was of growing importance, and James Watt realized that efficiency could be increased by using different cylinders for expansion and condensation of the steam. This drove his search for a linkage that could transform rotation of a crank into a linear slide, and resulted in his discovery of what is called Watt's linkage. This led to the study of linkages that could generate straight lines, even if only approximately; and inspired the mathematician J. J. Sylvester, who lectured on the Peaucellier linkage, which generates an exact straight line from a rotating crank.[5]

The work of Sylvester inspired A. B. Kempe, who showed that linkages for addition and multiplication could be assembled into a system that traced a given algebraic curve.[6] Kempe's design procedure has inspired research at the intersection of geometry and computer science.[7][8]

In the late 1800s F. Reuleaux, A. B. W. Kennedy, and L. Burmester formalized the analysis and synthesis of linkage systems using descriptive geometry, and P. L. Chebyshev introduced analytical techniques for the study and invention of linkages.[5]

In the mid-1900s F. Freudenstein and G. N. Sandor[9] used the newly developed digital computer to solve the loop equations of a linkage and determine its dimensions for a desired function, initiating the computer-aided design of linkages. Within two decades these computer techniques were integral to the analysis of complex machine systems[10][11] and the control of robot manipulators.[12]

R. E. Kaufman[13][14] combined the computer's ability to rapidly compute the roots of polynomial equations with a graphical user interface to unite Freudenstein's techniques with the geometrical methods of Reuleaux and Burmester and form KINSYN, an interactive computer graphics system for linkage design

The modern study of linkages includes the analysis and design of articulated systems that appear in robots, machine tools, and cable driven and tensegrity systems. These techniques are also being applied to biological systems and even the study of proteins.

Mobility

editThe configuration of a system of rigid links connected by ideal joints is defined by a set of configuration parameters, such as the angles around a revolute joint and the slides along prismatic joints measured between adjacent links. The geometric constraints of the linkage allow calculation of all of the configuration parameters in terms of a minimum set, which are the input parameters. The number of input parameters is called the mobility, or degree of freedom, of the linkage system.

A system of n rigid bodies moving in space has 6n degrees of freedom measured relative to a fixed frame. Include this frame in the count of bodies, so that mobility is independent of the choice of the fixed frame, then we have M = 6(N − 1), where N = n + 1 is the number of moving bodies plus the fixed body.

Joints that connect bodies in this system remove degrees of freedom and reduce mobility. Specifically, hinges and sliders each impose five constraints and therefore remove five degrees of freedom. It is convenient to define the number of constraints c that a joint imposes in terms of the joint's freedom f, where c = 6 − f. In the case of a hinge or slider, which are one degree of freedom joints, we have f = 1 and therefore c = 6 − 1 = 5.

Thus, the mobility of a linkage system formed from n moving links and j joints each with fi, i = 1, ..., j, degrees of freedom can be computed as,

where N includes the fixed link. This is known as Kutzbach–Grübler's equation

There are two important special cases: (i) a simple open chain, and (ii) a simple closed chain. A simple open chain consists of n moving links connected end to end by j joints, with one end connected to a ground link. Thus, in this case N = j + 1 and the mobility of the chain is

For a simple closed chain, n moving links are connected end-to-end by n+1 joints such that the two ends are connected to the ground link forming a loop. In this case, we have N=j and the mobility of the chain is

An example of a simple open chain is a serial robot manipulator. These robotic systems are constructed from a series of links connected by six one degree-of-freedom revolute or prismatic joints, so the system has six degrees of freedom.

An example of a simple closed chain is the RSSR (revolute-spherical-spherical-revolute) spatial four-bar linkage. The sum of the freedom of these joints is eight, so the mobility of the linkage is two, where one of the degrees of freedom is the rotation of the coupler around the line joining the two S joints.

Planar and spherical movement

editIt is common practice to design the linkage system so that the movement of all of the bodies are constrained to lie on parallel planes, to form what is known as a planar linkage. It is also possible to construct the linkage system so that all of the bodies move on concentric spheres, forming a spherical linkage. In both cases, the degrees of freedom of the link is now three rather than six, and the constraints imposed by joints are now c = 3 − f.

In this case, the mobility formula is given by

and we have the special cases,

- planar or spherical simple open chain,

- planar or spherical simple closed chain,

An example of a planar simple closed chain is the planar four-bar linkage, which is a four-bar loop with four one degree-of-freedom joints and therefore has mobility M = 1.

Joints

editThe most familiar joints for linkage systems are the revolute, or hinged, joint denoted by an R, and the prismatic, or sliding, joint denoted by a P. Most other joints used for spatial linkages are modeled as combinations of revolute and prismatic joints. For example,

- the cylindric joint consists of an RP or PR serial chain constructed so that the axes of the revolute and prismatic joints are parallel,

- the universal joint consists of an RR serial chain constructed such that the axes of the revolute joints intersect at a 90° angle;

- the spherical joint consists of an RRR serial chain for which each of the hinged joint axes intersect in the same point;

- the planar joint can be constructed either as a planar RRR, RPR, and PPR serial chain that has three degrees-of-freedom.

Analysis and synthesis of linkages

editThe primary mathematical tool for the analysis of a linkage is known as the kinematic equations of the system. This is a sequence of rigid body transformation along a serial chain within the linkage that locates a floating link relative to the ground frame. Each serial chain within the linkage that connects this floating link to ground provides a set of equations that must be satisfied by the configuration parameters of the system. The result is a set of non-linear equations that define the configuration parameters of the system for a set of values for the input parameters.

Freudenstein introduced a method to use these equations for the design of a planar four-bar linkage to achieve a specified relation between the input parameters and the configuration of the linkage. Another approach to planar four-bar linkage design was introduced by L. Burmester, and is called Burmester theory.

Planar one degree-of-freedom linkages

editThe mobility formula provides a way to determine the number of links and joints in a planar linkage that yields a one degree-of-freedom linkage. If we require the mobility of a planar linkage to be M = 1 and fi = 1, the result is

or

This formula shows that the linkage must have an even number of links, so we have

- N = 2, j = 1: this is a two-bar linkage known as the lever;

- N = 4, j = 4: this is the four-bar linkage;

- N = 6, j = 7: this is a six-bar linkage [ it has two links that have three joints, called ternary links, and there are two topologies of this linkage depending how these links are connected. In the Watt topology, the two ternary links are connected by a joint. In the Stephenson topology the two ternary links are connected by binary links;[15]

- N = 8, j = 10: the eight-bar linkage has 16 different topologies;

- N = 10, j = 13: the 10-bar linkage has 230 different topologies,

- N = 12, j = 16: the 12-bar has 6856 topologies.

See Sunkari and Schmidt[16] for the number of 14- and 16-bar topologies, as well as the number of linkages that have two, three and four degrees-of-freedom.

The planar four-bar linkage is probably the simplest and most common linkage. It is a one degree-of-freedom system that transforms an input crank rotation or slider displacement into an output rotation or slide.

Examples of four-bar linkages are:

- the crank-rocker, in which the input crank fully rotates and the output link rocks back and forth;

- the slider-crank, in which the input crank rotates and the output slide moves back and forth;

- drag-link mechanisms, in which the input crank fully rotates and drags the output crank in a fully rotational movement.

Biological linkages

editLinkage systems are widely distributed in animals. The most thorough overview of the different types of linkages in animals has been provided by Mees Muller,[17] who also designed a new classification system which is especially well suited for biological systems. A well-known example is the cruciate ligaments of the knee.

An important difference between biological and engineering linkages is that revolving bars are rare in biology and that usually only a small range of the theoretically possible is possible due to additional functional constraints (especially the necessity to deliver blood).[18] Biological linkages frequently are compliant. Often one or more bars are formed by ligaments, and often the linkages are three-dimensional. Coupled linkage systems are known, as well as five-, six-, and even seven-bar linkages.[17] Four-bar linkages are by far the most common though.

Linkages can be found in joints, such as the knee of tetrapods, the hock of sheep, and the cranial mechanism of birds and reptiles. The latter is responsible for the upward motion of the upper bill in many birds.

Linkage mechanisms are especially frequent and manifold in the head of bony fishes, such as wrasses, which have evolved many specialized feeding mechanisms. Especially advanced are the linkage mechanisms of jaw protrusion. For suction feeding a system of linked four-bar linkages is responsible for the coordinated opening of the mouth and 3-D expansion of the buccal cavity. Other linkages are responsible for protrusion of the premaxilla.

Linkages are also present as locking mechanisms, such as in the knee of the horse, which enables the animal to sleep standing, without active muscle contraction. In pivot feeding, used by certain bony fishes, a four-bar linkage at first locks the head in a ventrally bent position by the alignment of two bars. The release of the locking mechanism jets the head up and moves the mouth toward the prey within 5–10 ms.

Examples

edit- Pantograph (four-bar, two DOF)

- Five bar linkages often have meshing gears for two of the links, creating a one DOF linkage. They can provide greater power transmission with more design flexibility than four-bar linkages.

- Jansen's linkage is an eight-bar leg mechanism that was invented by kinetic sculptor Theo Jansen.

- Klann linkage is a six-bar linkage that forms a leg mechanism;

- Toggle mechanisms are four-bar linkages that are dimensioned so that they can fold and lock. The toggle positions are determined by the colinearity of two of the moving links.[19] The linkage is dimensioned so that the linkage reaches a toggle position just before it folds. The high mechanical advantage allows the input crank to deform the linkage just enough to push it beyond the toggle position. This locks the input in place. Toggle mechanisms are used as clamps.

Straight line mechanisms

edit- James Watt's parallel motion and Watt's linkage

- Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage, the first planar linkage to create a perfect straight line output from rotary input; eight-bar, one DOF.

- A Scott Russell linkage, which converts linear motion, to (almost) linear motion in a line perpendicular to the input.

- Chebyshev linkage, which provides nearly straight motion of a point with a four-bar linkage.

- Hoekens linkage, which provides nearly straight motion of a point with a four-bar linkage.

- Sarrus linkage, which provides motion of one surface in a direction normal to another.

- Hart's inversor, which provides a perfect straight line motion without sliding guides.[20]

Gallery

edit-

Rocker-slider function generator approximating the function Log(u) for 1 < u < 10.

-

Slider-rocker function generator approximating the function Tan(u) for 0 < u < 45°.

-

Fixed and moving centrodes of a four-bar linkage

-

Rack-and-pinion four-bar linkage

-

RTRTR mechanism

-

RTRTR mechanism

-

Gear five-bar mechanisms

-

3D slider-crank mechanism

-

Animated Pinocchio character

-

Crawford conicograph

-

Outward folding deployable mechanism

-

Inward folding deployable mechanism

See also

edit- Assur Groups

- Dwell mechanism

- Deployable structure

- Engineering mechanics

- Four-bar linkage

- Mechanical function generator

- Kinematics

- Kinematic coupling

- Kinematic pair

- Kinematic synthesis

- Kinematic models in Mathcad[24]

- Leg mechanism

- Lever

- Machine

- Outline of machines

- Overconstrained mechanism

- Parallel motion

- Reciprocating motion

- Slider-crank linkage

- Three-point hitch

References

edit- ^ Moubarak, P.; Ben-Tzvi, P. (2013). "On the Dual-Rod Slider Rocker Mechanism and Its Applications to Tristate Rigid Active Docking". Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics. 5 (1): 011010. doi:10.1115/1.4023178.

- ^ OED

- ^ Koetsier, T. (1986). "From Kinematically Generated Curves to Instantaneous Invariants: Episodes in the History of Instantaneous Planar Kinematics". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 21 (6): 489–498. doi:10.1016/0094-114x(86)90132-1.

- ^ A. P. Usher, 1929, A History of Mechanical Inventions, Harvard University Press, (reprinted by Dover Publications 1968)

- ^ a b F. C. Moon, "History of the Dynamics of Machines and Mechanisms from Leonardo to Timoshenko," International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms, (H. S. Yan and M. Ceccarelli, eds.), 2009. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9485-9-1

- ^ A. B. Kempe, "On a general method of describing plane curves of the nth degree by linkwork," Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, VII:213–216, 1876

- ^ Jordan, D.; Steiner, M. (1999). "Configuration Spaces of Mechanical Linkages". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 22 (2): 297–315. doi:10.1007/pl00009462.

- ^ R. Connelly and E. D. Demaine, "Geometry and Topology of Polygonal Linkages," Chapter 9, Handbook of discrete and computational geometry, (J. E. Goodman and J. O'Rourke, eds.), CRC Press, 2004

- ^ Freudenstein, F.; Sandor, G. N. (1959). "Synthesis of Path Generating Mechanisms by Means of a Programmed Digital Computer". Journal of Engineering for Industry. 81 (2): 159–168. doi:10.1115/1.4008283.

- ^ Sheth, P. N.; Uicker, J. J. (1972). "IMP (Integrated Mechanisms Program), A Computer-Aided Design Analysis system for Mechanisms and Linkages". Journal of Engineering for Industry. 94 (2): 454–464. doi:10.1115/1.3428176.

- ^ C. H. Suh and C. W. Radcliffe, Kinematics and Mechanism Design, John Wiley, pp:458, 1978

- ^ R. P. Paul, Robot Manipulators: Mathematics, Programming and Control, MIT Press, 1981

- ^ R. E. Kaufman and W. G. Maurer, "Interactive Linkage Synthesis on a Small Computer", ACM National Conference, Aug.3–5, 1971

- ^ A. J. Rubel and R. E. Kaufman, 1977, "KINSYN III: A New Human-Engineered System for Interactive Computer-aided Design of Planar Linkages," ASME Transactions, Journal of Engineering for Industry, May

- ^ Tsai, Lung-Wen (19 September 2000). L. W. Tsai, Mechanism design: enumeration of kinematic structures according to function, CRC Press, 2000. ISBN 9781420058420. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ Sunkari, R. P.; Schmidt, L. C. (2006). "Structural synthesis of planar kinematic chains by adapting a Mckay-type algorithm". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 41 (9): 1021–1030. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2005.11.007.

- ^ a b Muller, M. (1996). "A novel classification of planar four-bar linkages and its application to the mechanical analysis of animal systems". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 351 (1340): 689–720. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0065. PMID 8927640.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (November 24, 1996). "Why don't animals have wheels?". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ^ Robert L. Norton; Design of Machinery 5th Edition

- ^ "True straight-line linkages having a rectlinear translating bar" (PDF).

- ^ Simionescu, P.A. (2014). Computer Aided Graphing and Simulation Tools for AutoCAD users (1st ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-5290-3.

- ^ Simionescu, P.A. (21–24 August 2016). MeKin2D: Suite for Planar Mechanism Kinematics (PDF). ASME 2016 Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. Charlotte, NC, US. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Simionescu, P.A. (2016). "A restatement of the optimum synthesis of function generators with planar four-bar and slider-crank mechanisms examples". International Journal of Mechanisms and Robotic Systems. 3 (1): 60–79. doi:10.1504/IJMRS.2016.077038. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "PTC Community: Group: Kinematic models in Mathcad". Communities.ptc.com. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

Further reading

edit- Bryant, John; Sangwin, Chris (2008). How round is your circle? : where engineering and mathematics meet. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-691-13118-4. — Connections between mathematical and real-world mechanical models, historical development of precision machining, some practical advice on fabricating physical models, with ample illustrations and photographs

- Erdman, Arthur G.; Sandor, George N. (1984). Mechanism Design: Analysis and Synthesis. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-572396-5.

- Hartenberg, R.S. & J. Denavit (1964) Kinematic synthesis of linkages, New York: McGraw-Hill — Online link from Cornell University.

- Kidwell, Peggy Aldrich; Amy Ackerberg-Hastings; David Lindsay Roberts (2008). Tools of American mathematics teaching, 1800–2000. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 233–242. ISBN 978-0-8018-8814-4. — "Linkages: a peculiar fascination" (Chapter 14) is a discussion of mechanical linkage usage in American mathematical education, includes extensive references

- How to Draw a Straight Line — Historical discussion of linkage design from Cornell University

- Parmley, Robert. (2000). "Section 23: Linkage." Illustrated Sourcebook of Mechanical Components. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-048617-4 Drawings and discussion of various linkages.

- Sclater, Neil. (2011). "Linkages: Drives and Mechanisms." Mechanisms and Mechanical Devices Sourcebook. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 89–129. ISBN 978-0-07-170442-7. Drawings and designs of various linkages.

External links

edit- Kinematic Models for Design Digital Library (KMODDL) — Major web resource for kinematics. Movies and photos of hundreds of working mechanical-systems models in the Reuleaux Collection of Mechanisms and Machines at Cornell University, plus 5 other major collections. Includes an e-book library of dozens of classic texts on mechanical design and engineering. Includes CAD models and stereolithographic files for selected mechanisms.

- Digital Mechanism and Gear Library (DMG-Lib) (in German: Digitale Mechanismen- und Getriebebibliothek) — Online library about linkages and cams (mostly in German)

- Linkage calculations

- Introductory linkage lecture

- Virtual Mechanisms Animated by Java

- Linkage-based Drawing Apparatus by Robert Howsare

- (ASOM) Analysis, synthesis and optimization of multibar linkages

- Linkage animations on mechanicaldesign101.com include planar and spherical four-bar and six-bar linkages.

- Animations of planar and spherical four-bar linkages.

- Animation of Bennett's linkage.

- Example of a six-bar function generator that computes the elevation angle for a given range.

- Animations of six-bar linkage for a bicycle suspension.

- A variety of six-bar linkage designs.

- Introduction to Linkages

- An open source planar linkage mechanism simulation and mechanical synthesis system.