Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci[b] (15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect.[3] While his fame initially rested on his achievements as a painter, he has also become known for his notebooks, in which he made drawings and notes on a variety of subjects, including anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, painting, and palaeontology. Leonardo is widely regarded to have been a genius who epitomised the Renaissance humanist ideal,[4] and his collective works comprise a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by that of his younger contemporary Michelangelo.[3][4]

Leonardo da Vinci | |

|---|---|

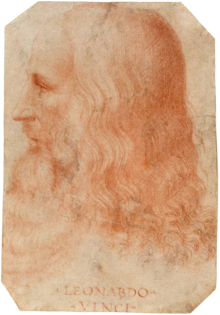

This portrait attributed to Francesco Melzi, c. 1515–1518, is the only certain contemporary depiction of Leonardo.[1][2] | |

| Born | Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci 15 April 1452 |

| Died | 2 May 1519 (aged 67) Clos Lucé, Amboise, Kingdom of France |

| Resting place | Château d'Amboise |

| Education | Studio of Andrea del Verrocchio |

| Years active | c. 1470–1519 |

| Known for |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | High Renaissance |

| Family | Da Vinci family |

| Signature | |

| |

Born out of wedlock to a successful notary and a lower-class woman in, or near, Vinci, he was educated in Florence by the Italian painter and sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio. He began his career in the city, but then spent much time in the service of Ludovico Sforza in Milan. Later, he worked in Florence and Milan again, as well as briefly in Rome, all while attracting a large following of imitators and students. Upon the invitation of Francis I, he spent his last three years in France, where he died in 1519. Since his death, there has not been a time where his achievements, diverse interests, personal life, and empirical thinking have failed to incite interest and admiration,[3][4] making him a frequent namesake and subject in culture.

Leonardo is identified as one of the greatest painters in the history of Western art and is often credited as the founder of the High Renaissance.[3] Despite having many lost works and fewer than 25 attributed major works – including numerous unfinished works – he created some of the most influential paintings in the Western canon.[3] The Mona Lisa is his best known work and is the world's most famous individual painting. The Last Supper is the most reproduced religious painting of all time and his Vitruvian Man drawing is also regarded as a cultural icon. In 2017, Salvator Mundi, attributed in whole or part to Leonardo,[5] was sold at auction for US$450.3 million, setting a new record for the most expensive painting ever sold at public auction.

Revered for his technological ingenuity, he conceptualised flying machines, a type of armoured fighting vehicle, concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be used in an adding machine,[6][7] and the double hull. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime, as the modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were only in their infancy during the Renaissance. Some of his smaller inventions, however, entered the world of manufacturing unheralded, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire. He made substantial discoveries in anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology, but he did not publish his findings and they had little to no direct influence on subsequent science.[8]

Biography

Early life (1452–1472)

Birth and background

Leonardo da Vinci, properly named Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci[b] ("Leonardo, son of ser Piero from Vinci"),[9][10][c] was born on 15 April 1452 in, or close to, the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, 20 miles from Florence.[11][12][d] He was born out of wedlock to Piero da Vinci (Ser Piero da Vinci d'Antonio di ser Piero di ser Guido; 1426–1504),[16] a Florentine legal notary,[11] and Caterina di Meo Lippi (c. 1434–1494), from the lower class.[17][18][e] It remains uncertain where Leonardo was born; the traditional account, from a local oral tradition recorded by the historian Emanuele Repetti,[21] is that he was born in Anchiano, a country hamlet that would have offered sufficient privacy for the illegitimate birth, though it is still possible he was born in a house in Florence that Ser Piero almost certainly had.[22][a] Leonardo's parents both married separately the year after his birth. Caterina – who later appears in Leonardo's notes as only "Caterina" or "Catelina" – is usually identified as the Caterina Buti del Vacca, who married the local artisan Antonio di Piero Buti del Vacca, nicknamed L'Accattabriga, 'the quarrelsome one'.[17][21] Having been betrothed to her the previous year, Ser Piero married Albiera Amadori and after her death in 1464, went on to have three subsequent marriages.[21][23][f] From all the marriages, Leonardo eventually had 16 half-siblings (of whom 11 survived infancy)[24] who were much younger than he (the last was born when Leonardo was 46 years old)[24] and with whom he had very little contact.[g]

Very little is known about Leonardo's childhood and much is shrouded in myth, partially because of his biography in the frequently apocryphal Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550) by 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari.[27][28] Tax records indicate that by at least 1457 he lived in the household of his paternal grandfather, Antonio da Vinci,[11] but it is possible that he spent the years before then in the care of his mother in Vinci, either Anchiano or Campo Zeppi in the parish of San Pantaleone.[29][30] He is thought to have been close to his uncle, Francesco da Vinci,[3] but his father was probably in Florence most of the time.[11] Ser Piero, who was the descendant of a long line of notaries, established an official residence in Florence by at least 1469 and had a successful career.[11] Despite his family history, Leonardo only received a basic and informal education in (vernacular) writing, reading, and mathematics; possibly because his artistic talents were recognised early, so his family decided to focus their attention there.[11]

Later in life, Leonardo recorded his earliest memory, now in the Codex Atlanticus.[31] While writing on the flight of birds, he recalled as an infant when a kite came to his cradle and opened his mouth with its tail; commentators still debate whether the anecdote was an actual memory or a fantasy.[32]

Verrocchio's workshop

In the mid-1460s, Leonardo's family moved to Florence, which at the time was the centre of Christian Humanist thought and culture.[33] Around the age of 14,[25] he became a garzone (studio boy) in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, who was the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his time.[33] This was about the time of the death of Verrocchio's master, the great sculptor Donatello.[h] Leonardo became an apprentice by the age of 17 and remained in training for seven years.[35] Other famous painters apprenticed in the workshop or associated with it include Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi.[36][37] Leonardo was exposed to both theoretical training and a wide range of technical skills,[38] including drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and woodwork, as well as the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modelling.[39][i]

Leonardo was a contemporary of Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Perugino, who were all slightly older than he was.[40] He would have met them at the workshop of Verrocchio or at the Platonic Academy of the Medici.[36] Florence was ornamented by the works of artists such as Donatello's contemporaries Masaccio, whose figurative frescoes were imbued with realism and emotion, and Ghiberti, whose Gates of Paradise, gleaming with gold leaf, displayed the art of combining complex figure compositions with detailed architectural backgrounds. Piero della Francesca had made a detailed study of perspective,[41] and was the first painter to make a scientific study of light. These studies and Leon Battista Alberti's treatise De pictura were to have a profound effect on younger artists and in particular on Leonardo's own observations and artworks.[34][42]

Much of the painting in Verrocchio's workshop was done by his assistants. According to Vasari, Leonardo collaborated with Verrocchio on his The Baptism of Christ (c. 1472–1475), painting the young angel holding Jesus's robe with skill so far superior to his master's that Verrocchio purportedly put down his brush and never painted again[‡ 1] (the latter claim probably being apocryphal).[14] The new technique of oil paint was applied to areas of the mostly tempera work, including the landscape, the rocks seen through the brown mountain stream, and much of Jesus's figure, indicating Leonardo's hand.[43] Additionally, Leonardo may have been a model for two works by Verrocchio: the bronze statue of David in the Bargello and the archangel Raphael in Tobias and the Angel.[14]

Vasari tells a story of Leonardo as a very young man: a local peasant made himself a round buckler shield and requested that Ser Piero have it painted for him. Leonardo, inspired by the story of Medusa, responded with a painting of a monster spitting fire that was so terrifying that his father bought a different shield to give to the peasant and sold Leonardo's to a Florentine art dealer for 100 ducats, who in turn sold it to the Duke of Milan.[‡ 2]

First Florentine period (1472 – c. 1482)

By 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine,[j] but even after his father set him up in his own workshop, his attachment to Verrocchio was such that he continued to collaborate and live with him.[36][44] Leonardo's earliest known dated work is a 1473 pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno valley (see below).[37][45][k] According to Vasari, the young Leonardo was the first to suggest making the Arno river a navigable channel between Florence and Pisa.[46]

In January 1478, Leonardo received an independent commission to paint an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in the Palazzo Vecchio,[47] an indication of his independence from Verrocchio's studio. An anonymous early biographer, known as Anonimo Gaddiano, claims that in 1480 Leonardo was living with the Medici and often worked in the garden of the Piazza San Marco, Florence, where a Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets and philosophers organised by the Medici met.[14][l] In March 1481, he received a commission from the monks of San Donato in Scopeto for The Adoration of the Magi.[48] Neither of these initial commissions were completed, being abandoned when Leonardo went to offer his services to Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza. Leonardo wrote Sforza a letter which described the diverse things that he could achieve in the fields of engineering and weapon design, and mentioned that he could paint.[37][49] He brought with him a silver string instrument – either a lute or lyre – in the form of a horse's head.[49]

With Alberti, Leonardo visited the home of the Medici and through them came to know the older Humanist philosophers of whom Marsiglio Ficino, proponent of Neoplatonism; Cristoforo Landino, writer of commentaries on Classical writings, and John Argyropoulos, teacher of Greek and translator of Aristotle were the foremost. Also associated with the Platonic Academy of the Medici was Leonardo's contemporary, the brilliant young poet and philosopher Pico della Mirandola.[40][42][50] In 1482, Leonardo was sent as an ambassador by Lorenzo de' Medici to Ludovico il Moro, who ruled Milan between 1479 and 1499.[40][14]

-

Landscape of the Arno Valley (1473)

-

Sketch of the hanging of Bernardo Bandini Baroncelli, 1479

First Milanese period (c. 1482–1499)

Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482 until 1499. He was commissioned to paint the Virgin of the Rocks for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie.[51] In the spring of 1485, Leonardo travelled to Hungary (on behalf of Sforza) to meet king Matthias Corvinus, and was commissioned by him to paint a Madonna.[52] In 1490 he was called as a consultant, together with Francesco di Giorgio Martini, for the building site of the cathedral of Pavia[53][54] and was struck by the equestrian statue of Regisole, of which he left a sketch.[55] Leonardo was employed on many other projects for Sforza, such as preparation of floats and pageants for special occasions; a drawing of, and wooden model for, a competition to design the cupola for Milan Cathedral;[56] and a model for a huge equestrian monument to Ludovico's predecessor Francesco Sforza. This would have surpassed in size the only two large equestrian statues of the Renaissance, Donatello's Gattamelata in Padua and Verrocchio's Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice, and became known as the Gran Cavallo.[37] Leonardo completed a model for the horse and made detailed plans for its casting,[37] but in November 1494, Ludovico gave the metal to his brother-in-law to be used for a cannon to defend the city from Charles VIII of France.[37]

Contemporary correspondence records that Leonardo and his assistants were commissioned by the Duke of Milan to paint the Sala delle Asse in the Sforza Castle, c. 1498.[57] The project became a trompe-l'œil decoration that made the great hall appear to be a pergola created by the interwoven limbs of sixteen mulberry trees,[58] whose canopy included an intricate labyrinth of leaves and knots on the ceiling.[59]

-

La Belle Ferronnière, c. 1490–1498

-

Detail of 1902 restoration, trompe-l'œil painting (1498)

Second Florentine period (1500–1508)

When Ludovico Sforza was overthrown by France in 1500, Leonardo fled Milan for Venice, accompanied by his assistant Salaì and friend, the mathematician Luca Pacioli.[61] In Venice, Leonardo was employed as a military architect and engineer, devising methods to defend the city from naval attack.[36] On his return to Florence in 1500, he and his household were guests of the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata and were provided with a workshop where, according to Vasari, Leonardo created the cartoon of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist, a work that won such admiration that "men [and] women, young and old" flocked to see it "as if they were going to a solemn festival."[‡ 3][m]

In Cesena in 1502, Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, acting as a military architect and engineer and travelling throughout Italy with his patron.[61] Leonardo created a map of Cesare Borgia's stronghold, a town plan of Imola in order to win his patronage. Upon seeing it, Cesare hired Leonardo as his chief military engineer and architect. Later in the year, Leonardo produced another map for his patron, one of Chiana Valley, Tuscany, so as to give his patron a better overlay of the land and greater strategic position. He created this map in conjunction with his other project of constructing a dam from the sea to Florence, in order to allow a supply of water to sustain the canal during all seasons.

Leonardo had left Borgia's service and returned to Florence by early 1503,[63] where he rejoined the Guild of Saint Luke on 18 October of that year. By this same month, Leonardo had begun working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model for the Mona Lisa,[64][65] which he would continue working on until his twilight years. In January 1504, he was part of a committee formed to recommend where Michelangelo's statue of David should be placed.[66] He then spent two years in Florence designing and painting a mural of The Battle of Anghiari for the Signoria,[61] with Michelangelo designing its companion piece, The Battle of Cascina.[n]

In 1506, Leonardo was summoned to Milan by Charles II d'Amboise, the acting French governor of the city.[69] There, Leonardo took on another pupil, Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat, who is considered to have been his favourite student.[36] The Council of Florence wished Leonardo to return promptly to finish The Battle of Anghiari, but he was given leave at the behest of Louis XII, who considered commissioning the artist to make some portraits.[69] Leonardo may have commenced a project for an equestrian figure of d'Amboise;[70] a wax model survives and, if genuine, is the only extant example of Leonardo's sculpture. Leonardo was otherwise free to pursue his scientific interests.[69] Many of Leonardo's most prominent pupils either knew or worked with him in Milan,[36] including Bernardino Luini, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, and Marco d'Oggiono. In 1507, Leonardo was in Florence sorting out a dispute with his brothers over the estate of his father, who had died in 1504.

-

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, c. 1501–1519, Louvre, Paris

-

Leonardo's map of Imola, created for Cesare Borgia, 1502

Second Milanese period (1508–1513)

By 1508, Leonardo was back in Milan, living in his own house in Porta Orientale in the parish of Santa Babila.[71]

In 1512, Leonardo was working on plans for an equestrian monument for Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, but this was prevented by an invasion of a confederation of Swiss, Spanish and Venetian forces, which drove the French from Milan. Leonardo stayed in the city, spending several months in 1513 at the Medici's Vaprio d'Adda villa.[72]

Rome and France (1513–1519)

In March 1513, Lorenzo de' Medici's son Giovanni assumed the papacy (as Leo X); Leonardo went to Rome that September, where he was received by the pope's brother Giuliano.[72] From September 1513 to 1516, Leonardo spent much of his time living in the Belvedere Courtyard in the Apostolic Palace, where Michelangelo and Raphael were both active.[71] Leonardo was given an allowance of 33 ducats a month and, according to Vasari, decorated a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver.[74] The pope gave him a painting commission of unknown subject matter, but cancelled it when the artist set about developing a new kind of varnish.[74][o] Leonardo became ill, in what may have been the first of multiple strokes leading to his death.[74] He practised botany in the Vatican Gardens, and was commissioned to make plans for the Pope's proposed draining of the Pontine Marshes.[75] He also dissected cadavers, making notes for a treatise on vocal cords;[76] these he gave to an official in hopes of regaining the Pope's favour, but he was unsuccessful.[74]

In October 1515, King Francis I of France recaptured Milan.[48][p] On 21 March 1516 Antonio Maria Pallavicini, the French ambassador to the Holy See, received a letter sent from Lyon a week previously by the royal advisor Guillaume Gouffier, seigneur de Bonnivet, containing the French king's instructions to assist Leonardo in his relocation to France and to inform the artist that the King was eagerly awaiting his arrival. Pallavicini was also asked to reassure Leonardo that he would be well received at court, both by the King and by his mother, Louise of Savoy.[78] Leonardo entered Francis's service later that year, and was given the use of the manor house Clos Lucé near the King's residence at the royal Château d'Amboise. He was frequently visited by Francis, and drew plans for an immense castle town the King intended to erect at Romorantin. He also made a mechanical lion, which during a pageant walked towards the King and – upon being struck by a wand – opened its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies.[79][‡ 3][q]

Leonardo was accompanied during this time by his friend and apprentice Francesco Melzi, and was supported by a pension totalling 10,000 scudi.[71] At some point, Melzi drew a portrait of Leonardo; the only others known from his lifetime were a sketch by an unknown assistant on the back of one of Leonardo's studies (c. 1517)[81] and a drawing by Giovanni Ambrogio Figino depicting an elderly Leonardo with his right arm wrapped in clothing.[82][r] The latter, in addition to the record of an October 1517 visit by Louis d'Aragon,[s] confirms an account of Leonardo's right hand being paralytic when he was 65,[85] which may indicate why he left works such as the Mona Lisa unfinished.[83][86][87] He continued to work at some capacity until eventually becoming ill and bedridden for several months.[85]

Death

Leonardo died at Clos Lucé on 2 May 1519 at the age of 67, possibly of a stroke.[88][87][89] Francis I had become a close friend. Vasari describes Leonardo as lamenting on his deathbed, full of repentance, that "he had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done."[90] Vasari states that in his last days, Leonardo sent for a priest to make his confession and to receive the Holy Sacrament.[‡ 4] Vasari also records that the King held Leonardo's head in his arms as he died, although this story may be legend rather than fact.[t][u] In accordance with his will, sixty beggars carrying tapers followed Leonardo's casket.[50][v] Melzi was the principal heir and executor, receiving, as well as money, Leonardo's paintings, tools, library and personal effects. Leonardo's other long-time pupil and companion, Salaì, and his servant Baptista de Vilanis, each received half of Leonardo's vineyards.[92] His brothers received land, and his serving woman received a fur-lined cloak. On 12 August 1519, Leonardo's remains were interred in the Collegiate Church of Saint Florentin at the Château d'Amboise.[93]

Some 20 years after Leonardo's death, Francis was reported by the goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini as saying: "There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher."[94]

Salaì, or Il Salaino ("The Little Unclean One", i.e., the devil), entered Leonardo's household in 1490 as an assistant. After only a year, Leonardo made a list of his misdemeanours, calling him "a thief, a liar, stubborn, and a glutton," after he had made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions and spent a fortune on clothes.[95] Nevertheless, Leonardo treated him with great indulgence, and he remained in Leonardo's household for the next thirty years.[96] Salaì executed a number of paintings under the name of Andrea Salaì, but although Vasari claims that Leonardo "taught him many things about painting,"[‡ 3] his work is generally considered to be of less artistic merit than others among Leonardo's pupils, such as Marco d'Oggiono and Boltraffio.

At the time of his death in 1524, Salaì owned a painting referred to as Joconda in a posthumous inventory of his belongings; it was assessed at 505 lire, an exceptionally high valuation for a small panel portrait.[97]

Personal life

Despite the thousands of pages Leonardo left in notebooks and manuscripts, he scarcely made reference to his personal life.[2]

Within Leonardo's lifetime, his extraordinary powers of invention, his "great physical beauty" and "infinite grace," as described by Vasari,[‡ 5] as well as all other aspects of his life, attracted the curiosity of others. One such aspect was his love for animals, likely including vegetarianism and according to Vasari, a habit of purchasing caged birds and releasing them.[99][‡ 6]

Leonardo had many friends who are now notable either in their fields or for their historical significance, including mathematician Luca Pacioli,[100] with whom he collaborated on the book Divina proportione in the 1490s. Leonardo appears to have had no close relationships with women except for his friendship with Cecilia Gallerani and the two Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella.[101] While on a journey that took him through Mantua, he drew a portrait of Isabella that appears to have been used to create a painted portrait, now lost.[36]

Beyond friendship, Leonardo kept his private life secret. His sexuality has been the subject of satire, analysis, and speculation. This trend began in the mid-16th century and was revived in the 19th and 20th centuries, most notably by Sigmund Freud in his Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood.[102] Leonardo's most intimate relationships were perhaps with his pupils Salaì and Melzi. Melzi, writing to inform Leonardo's brothers of his death, described Leonardo's feelings for his pupils as both loving and passionate. It has been claimed since the 16th century that these relationships were of a sexual or erotic nature. Walter Isaacson in his biography of Leonardo makes explicit his opinion that the relations with Salaì were intimate and homosexual.[103]

Earlier in Leonardo's life, court records of 1476, when he was aged twenty-four, show that Leonardo and three other young men were charged with sodomy in an incident involving a known male prostitute. The charges were dismissed for lack of evidence, and there is speculation that since one of the accused, Lionardo de Tornabuoni, was related to Lorenzo de' Medici, the family exerted its influence to secure the dismissal.[104] Since that date much has been written about his presumed homosexuality[105] and its role in his art, particularly in the androgyny and eroticism manifested in Saint John the Baptist and Bacchus and more explicitly in a number of erotic drawings.[106][98]

Paintings

Despite the recent awareness and admiration of Leonardo as a scientist and inventor, for the better part of four hundred years his fame rested on his achievements as a painter. A handful of works that are either authenticated or attributed to him have been regarded as among the great masterpieces. These paintings are famous for a variety of qualities that have been much imitated by students and discussed at great length by connoisseurs and critics. By the 1490s Leonardo had already been described as a "Divine" painter.[107]

Among the qualities that make Leonardo's work unique are his innovative techniques for laying on the paint; his detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany and geology; his interest in physiognomy and the way humans register emotion in expression and gesture; his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition; and his use of subtle gradation of tone. All these qualities come together in his most famous painted works, the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, and the Virgin of the Rocks.[w]

Early works

Leonardo first gained attention for his work on the Baptism of Christ, painted in conjunction with Verrocchio. Two other paintings appear to date from his time at Verrocchio's workshop, both of which are Annunciations. One is small, 59 centimetres (23 in) long and 14 cm (5.5 in) high. It is a "predella" to go at the base of a larger composition, a painting by Lorenzo di Credi from which it has become separated. The other is a much larger work, 217 cm (85 in) long.[108] In both Annunciations, Leonardo used a formal arrangement, like two well-known pictures by Fra Angelico of the same subject, of the Virgin Mary sitting or kneeling to the right of the picture, approached from the left by an angel in profile, with a rich flowing garment, raised wings and bearing a lily. Although previously attributed to Ghirlandaio, the larger work is now generally attributed to Leonardo.[109]

In the smaller painting, Mary averts her eyes and folds her hands in a gesture that symbolised submission to God's will. Mary is not submissive, however, in the larger piece. The girl, interrupted in her reading by this unexpected messenger, puts a finger in her bible to mark the place and raises her hand in a formal gesture of greeting or surprise.[34] This calm young woman appears to accept her role as the Mother of God, not with resignation but with confidence. In this painting, the young Leonardo presents the humanist face of the Virgin Mary, recognising humanity's role in God's incarnation.

Paintings of the 1480s

In the 1480s, Leonardo received two very important commissions and commenced another work that was of ground-breaking importance in terms of composition. Two of the three were never finished, and the third took so long that it was subject to lengthy negotiations over completion and payment.

One of these paintings was Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, which Bortolon associates with a difficult period of Leonardo's life, as evidenced in his diary: "I thought I was learning to live; I was only learning to die."[36] Although the painting is barely begun, the composition can be seen and is very unusual.[x] Jerome, as a penitent, occupies the middle of the picture, set on a slight diagonal and viewed somewhat from above. His kneeling form takes on a trapezoid shape, with one arm stretched to the outer edge of the painting and his gaze looking in the opposite direction. J. Wasserman points out the link between this painting and Leonardo's anatomical studies.[110] Across the foreground sprawls his symbol, a great lion whose body and tail make a double spiral across the base of the picture space. The other remarkable feature is the sketchy landscape of craggy rocks against which the figure is silhouetted.

The daring display of figure composition, the landscape elements and personal drama also appear in the great unfinished masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, a commission from the Monks of San Donato a Scopeto. It is a complex composition, of about 250 x 250 centimetres. Leonardo did numerous drawings and preparatory studies, including a detailed one in linear perspective of the ruined classical architecture that forms part of the background. In 1482 Leonardo went to Milan at the behest of Lorenzo de' Medici in order to win favour with Ludovico il Moro, and the painting was abandoned.[14]

The third important work of this period is the Virgin of the Rocks, commissioned in Milan for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception. The painting, to be done with the assistance of the de Predis brothers, was to fill a large complex altarpiece.[111] Leonardo chose to paint an apocryphal moment of the infancy of Christ when the infant John the Baptist, in protection of an angel, met the Holy Family on the road to Egypt. The painting demonstrates an eerie beauty as the graceful figures kneel in adoration around the infant Christ in a wild landscape of tumbling rock and whirling water.[112] While the painting is quite large, about 200×120 centimetres, it is not nearly as complex as the painting ordered by the monks of San Donato, having only four figures rather than about fifty and a rocky landscape rather than architectural details. The painting was eventually finished; in fact, two versions of the painting were finished: one remained at the chapel of the Confraternity, while Leonardo took the other to France. The Brothers did not get their painting, however, nor the de Predis their payment, until the next century.[37][61]

Leonardo's most remarkable portrait of this period is the Lady with an Ermine, presumed to be Cecilia Gallerani (c. 1483–1490), lover of Ludovico Sforza.[113][114] The painting is characterised by the pose of the figure with the head turned at a very different angle to the torso, unusual at a date when many portraits were still rigidly in profile. The ermine plainly carries symbolic meaning, relating either to the sitter, or to Ludovico who belonged to the prestigious Order of the Ermine.[113]

Paintings of the 1490s

Leonardo's most famous painting of the 1490s is The Last Supper, commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan. It represents the last meal shared by Jesus with his disciples before his capture and death, and shows the moment when Jesus has just said "one of you will betray me", and the consternation that this statement caused.[37]

The writer Matteo Bandello observed Leonardo at work and wrote that some days he would paint from dawn till dusk without stopping to eat and then not paint for three or four days at a time.[115] This was beyond the comprehension of the prior of the convent, who hounded him until Leonardo asked Ludovico to intervene. Vasari describes how Leonardo, troubled over his ability to adequately depict the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, told the duke that he might be obliged to use the prior as his model.[‡ 7]

The painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece of design and characterisation,[‡ 8] but it deteriorated rapidly, so that within a hundred years it was described by one viewer as "completely ruined."[116] Leonardo, instead of using the reliable technique of fresco, had used tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso, resulting in a surface subject to mould and to flaking.[117] Despite this, the painting remains one of the most reproduced works of art; countless copies have been made in various mediums.

Toward the end of this period, in 1498 Leonardo's trompe-l'œil decoration of the Sala delle Asse was painted for the Duke of Milan in the Castello Sforzesco.

Paintings of the 1500s

In 1505, Leonardo was commissioned to paint The Battle of Anghiari in the Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the Five Hundred) in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Leonardo devised a dynamic composition depicting four men riding raging war horses engaged in a battle for possession of a standard, at the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. Michelangelo was assigned the opposite wall to depict the Battle of Cascina. Leonardo's painting deteriorated rapidly and is now known from a copy by Rubens.[118]

Among the works created by Leonardo in the 16th century is the small portrait known as the Mona Lisa or La Gioconda, the laughing one. In the present era, it is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Its fame rests, in particular, on the elusive smile on the woman's face, its mysterious quality perhaps due to the subtly shadowed corners of the mouth and eyes such that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined. The shadowy quality for which the work is renowned came to be called "sfumato", or Leonardo's smoke. Vasari wrote that the smile was "so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original."[‡ 9]

Other characteristics of the painting are the unadorned dress, in which the eyes and hands have no competition from other details; the dramatic landscape background, in which the world seems to be in a state of flux; the subdued colouring; and the extremely smooth nature of the painterly technique, employing oils laid on much like tempera, and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable.[119] Vasari expressed that the painting's quality would make even "the most confident master ... despair and lose heart."[‡ 10] The perfect state of preservation and the fact that there is no sign of repair or overpainting is rare in a panel painting of this date.[120]

In the painting Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, the composition again picks up the theme of figures in a landscape, which Wasserman describes as "breathtakingly beautiful"[121] and harkens back to the Saint Jerome with the figure set at an oblique angle. What makes this painting unusual is that there are two obliquely set figures superimposed. Mary is seated on the knee of her mother, Saint Anne. She leans forward to restrain the Christ Child as he plays roughly with a lamb, the sign of his own impending sacrifice.[37] This painting, which was copied many times, influenced Michelangelo, Raphael, and Andrea del Sarto,[122] and through them Pontormo and Correggio. The trends in composition were adopted in particular by the Venetian painters Tintoretto and Veronese.

Drawings

Leonardo was a prolific draughtsman, keeping journals full of small sketches and detailed drawings recording all manner of things that took his attention. As well as the journals there exist many studies for paintings, some of which can be identified as preparatory to particular works such as The Adoration of the Magi, The Virgin of the Rocks and The Last Supper.[123] His earliest dated drawing is a Landscape of the Arno Valley, 1473, which shows the river, the mountains, Montelupo Castle and the farmlands beyond it in great detail.[36][123][y]

Among his famous drawings are the Vitruvian Man, a study of the proportions of the human body; the Head of an Angel, for The Virgin of the Rocks in the Louvre; a botanical study of Star of Bethlehem; and a large drawing (160×100 cm) in black chalk on coloured paper of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist in the National Gallery, London.[123] This drawing employs the subtle sfumato technique of shading, in the manner of the Mona Lisa. It is thought that Leonardo never made a painting from it, the closest similarity being to The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne in the Louvre.[124]

Other drawings of interest include numerous studies generally referred to as "caricatures" because, although exaggerated, they appear to be based upon observation of live models. Vasari relates that Leonardo would look for interesting faces in public to use as models for some of his work.[‡ 7] There are numerous studies of beautiful young men, often associated with Salaì, with the rare and much admired facial feature, the so-called "Grecian profile".[z] These faces are often contrasted with that of a warrior.[123] Salaì is often depicted in fancy-dress costume. Leonardo is known to have designed sets for pageants with which these may be associated. Other, often meticulous, drawings show studies of drapery. A marked development in Leonardo's ability to draw drapery occurred in his early works. Another often-reproduced drawing is a macabre sketch that was done by Leonardo in Florence in 1479 showing the body of Bernardo Baroncelli, hanged in connection with the murder of Giuliano, brother of Lorenzo de' Medici, in the Pazzi conspiracy.[123] In his notes, Leonardo recorded the colours of the robes that Baroncelli was wearing when he died.

Like the two contemporary architects Donato Bramante (who designed the Belvedere Courtyard) and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder, Leonardo experimented with designs for centrally planned churches, a number of which appear in his journals, as both plans and views, although none was ever realised.[40][125]

Journals and notes

Renaissance humanism recognised no mutually exclusive polarities between the sciences and the arts, and Leonardo's studies in science and engineering are sometimes considered as impressive and innovative as his artistic work.[37] These studies were recorded in 13,000 pages of notes and drawings, which fuse art and natural philosophy (the forerunner of modern science). They were made and maintained daily throughout Leonardo's life and travels, as he made continual observations of the world around him.[37] Leonardo's notes and drawings display an enormous range of interests and preoccupations, some as mundane as lists of groceries and people who owed him money and some as intriguing as designs for wings and shoes for walking on water. There are compositions for paintings, studies of details and drapery, studies of faces and emotions, of animals, babies, dissections, plant studies, rock formations, whirlpools, war machines, flying machines and architecture.[37]

These notebooks – originally loose papers of different types and sizes – were largely entrusted to Leonardo's pupil and heir Francesco Melzi after the master's death.[126] These were to be published, a task of overwhelming difficulty because of its scope and Leonardo's idiosyncratic writing.[127] Some of Leonardo's drawings were copied by an anonymous Milanese artist for a planned treatise on art c. 1570.[128] After Melzi's death in 1570, the collection passed to his son, the lawyer Orazio, who initially took little interest in the journals.[126] In 1587, a Melzi household tutor named Lelio Gavardi took 13 of the manuscripts to Pisa; there, the architect Giovanni Magenta reproached Gavardi for having taken the manuscripts illicitly and returned them to Orazio. Having many more such works in his possession, Orazio gifted the volumes to Magenta. News spread of these lost works of Leonardo's, and Orazio retrieved seven of the 13 manuscripts, which he then gave to Pompeo Leoni for publication in two volumes; one of these was the Codex Atlanticus. The other six works had been distributed to a few others.[129] After Orazio's death, his heirs sold the rest of Leonardo's possessions, and thus began their dispersal.[130]

Some works have found their way into major collections such as the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, the Louvre, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, which holds the 12-volume Codex Atlanticus, and the British Library in London, which has put a selection from the Codex Arundel (BL Arundel MS 263) online.[131] Works have also been at Holkham Hall, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in the private hands of John Nicholas Brown I and Robert Lehman.[126] The Codex Leicester is the only privately owned major scientific work of Leonardo; it is owned by Bill Gates and displayed once a year in different cities around the world.

Most of Leonardo's writings are in mirror-image cursive.[45][132] Since Leonardo wrote with his left hand, it was probably easier for him to write from right to left.[133][aa] Leonardo used a variety of shorthand and symbols, and states in his notes that he intended to prepare them for publication.[132] In many cases a single topic is covered in detail in both words and pictures on a single sheet, together conveying information that would not be lost if the pages were published out of order.[136] Why they were not published during Leonardo's lifetime is unknown.[37]

Science and inventions

Leonardo's approach to science was observational: he tried to understand a phenomenon by describing and depicting it in utmost detail and did not emphasise experiments or theoretical explanation. Since he lacked formal education in Latin and mathematics, contemporary scholars mostly ignored Leonardo the scientist, although he did teach himself Latin. His keen observations in many areas were noted, such as when he wrote "Il sole non si move." ("The Sun does not move.")[137]

In the 1490s he studied mathematics under Luca Pacioli and prepared a series of drawings of regular solids in a skeletal form to be engraved as plates for Pacioli's book Divina proportione, published in 1509.[37] While living in Milan, he studied light from the summit of Monte Rosa.[69] Scientific writings in his notebook on fossils have been considered as influential on early palaeontology.[138]

The content of his journals suggest that he was planning a series of treatises on a variety of subjects. A coherent treatise on anatomy is said to have been observed during a visit by Cardinal Louis d'Aragon's secretary in 1517.[139] Aspects of his work on the studies of anatomy, light and the landscape were assembled for publication by Melzi and eventually published as A Treatise on Painting in France and Italy in 1651 and Germany in 1724,[140] with engravings based upon drawings by the Classical painter Nicolas Poussin.[4] According to Arasse, the treatise, which in France went into 62 editions in fifty years, caused Leonardo to be seen as "the precursor of French academic thought on art."[37]

While Leonardo's experimentation followed scientific methods, a recent and exhaustive analysis of Leonardo as a scientist by Fritjof Capra argues that Leonardo was a fundamentally different kind of scientist from Galileo, Newton and other scientists who followed him in that, as a "Renaissance Man", his theorising and hypothesising integrated the arts and particularly painting.[141]

Anatomy and physiology

Leonardo started his study in the anatomy of the human body under the apprenticeship of Verrocchio, who demanded that his students develop a deep knowledge of the subject. As an artist, he quickly became master of topographic anatomy, drawing many studies of muscles, tendons and other visible anatomical features.[citation needed]

As a successful artist, Leonardo was given permission to dissect human corpses at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence and later at hospitals in Milan and Rome. From 1510 to 1511 he collaborated in his studies with the doctor Marcantonio della Torre, professor of Anatomy at the University of Pavia.[142] Leonardo made over 240 detailed drawings and wrote about 13,000 words toward a treatise on anatomy.[143] Only a small amount of the material on anatomy was published in Leonardo's Treatise on painting.[127] During the time that Melzi was ordering the material into chapters for publication, they were examined by a number of anatomists and artists, including Vasari, Cellini and Albrecht Dürer, who made a number of drawings from them.[127]

Leonardo's anatomical drawings include many studies of the human skeleton and its parts, and of muscles and sinews. He studied the mechanical functions of the skeleton and the muscular forces that are applied to it in a manner that prefigured the modern science of biomechanics.[144] He drew the heart and vascular system, the sex organs and other internal organs, making one of the first scientific drawings of a fetus in utero.[123] The drawings and notation are far ahead of their time, and if published would undoubtedly have made a major contribution to medical science.[143]

Leonardo also closely observed and recorded the effects of age and of human emotion on the physiology, studying in particular the effects of rage. He drew many figures who had significant facial deformities or signs of illness.[37][123] Leonardo also studied and drew the anatomy of many animals, dissecting cows, birds, monkeys, bears, and frogs, and comparing in his drawings their anatomical structure with that of humans. He also made a number of studies of horses.[123]

Leonardo's dissections and documentation of muscles, nerves, and vessels helped to describe the physiology and mechanics of movement. He attempted to identify the source of 'emotions' and their expression. He found it difficult to incorporate the prevailing system and theories of bodily humours, but eventually he abandoned these physiological explanations of bodily functions. He made the observations that humours were not located in cerebral spaces or ventricles. He documented that the humours were not contained in the heart or the liver, and that it was the heart that defined the circulatory system. He was the first to define atherosclerosis and liver cirrhosis. He created models of the cerebral ventricles with the use of melted wax and constructed a glass aorta to observe the circulation of blood through the aortic valve by using water and grass seed to watch flow patterns.[145]

Engineering and inventions

During his lifetime, Leonardo was also valued as an engineer. With the same rational and analytical approach that moved him to represent the human body and to investigate anatomy, Leonardo studied and designed many machines and devices. He drew their "anatomy" with unparalleled mastery, producing the first form of the modern technical drawing, including a perfected "exploded view" technique, to represent internal components. Those studies and projects collected in his codices fill more than 5,000 pages.[146] In a letter of 1482 to the lord of Milan Ludovico il Moro, he wrote that he could create all sorts of machines both for the protection of a city and for siege. When he fled from Milan to Venice in 1499, he found employment as an engineer and devised a system of moveable barricades to protect the city from attack. In 1502, he created a scheme for diverting the flow of the Arno river, a project on which Niccolò Machiavelli also worked.[147][148] He continued to contemplate the canalisation of Lombardy's plains while in Louis XII's company[69] and of the Loire and its tributaries in the company of Francis I.[149] Leonardo's journals include a vast number of inventions, both practical and impractical. They include musical instruments, a mechanical knight, hydraulic pumps, reversible crank mechanisms, finned mortar shells, and a steam cannon.[36][37]

Leonardo was fascinated by the phenomenon of flight for much of his life, producing many studies, including Codex on the Flight of Birds (c. 1505), as well as plans for several flying machines, such as a flapping ornithopter and a machine with a helical rotor.[37] In a 2003 documentary by British television station Channel Four, titled Leonardo's Dream Machines, various designs by Leonardo, such as a parachute and a giant crossbow, were interpreted and constructed.[150][151] Some of those designs proved successful, whilst others fared less well when tested. Similarly, a team of engineers built ten machines designed by Leonardo in the 2009 American television series Doing DaVinci, including a fighting vehicle and a self-propelled cart.

Research performed by Marc van den Broek revealed older prototypes for more than 100 inventions that are ascribed to Leonardo. Similarities between Leonardo's illustrations and drawings from the Middle Ages and from Ancient Greece and Rome, the Chinese and Persian Empires, and Egypt suggest that a large portion of Leonardo's inventions had been conceived before his lifetime. Leonardo's innovation was to combine different functions from existing drafts and set them into scenes that illustrated their utility. By reconstituting technical inventions he created something new.[152]

In his notebooks, Leonardo first stated the 'laws' of sliding friction in 1493.[153] His inspiration for investigating friction came about in part from his study of perpetual motion, which he correctly concluded was not possible.[154] His results were never published and the friction laws were not rediscovered until 1699 by Guillaume Amontons, with whose name they are now usually associated.[‡ 7] For this contribution, Leonardo was named as the first of the 23 "Men of Tribology" by Duncan Dowson.[155]

Legacy

Although he had no formal academic training,[156] many historians and scholars regard Leonardo as the prime exemplar of the "Universal Genius" or "Renaissance Man", an individual of "unquenchable curiosity" and "feverishly inventive imagination."[157] He is widely considered one of the most diversely talented individuals ever to have lived.[158] According to art historian Helen Gardner, the scope and depth of his interests were without precedent in recorded history, and "his mind and personality seem to us superhuman, while the man himself mysterious and remote."[157] Scholars interpret his view of the world as being based in logic, though the empirical methods he used were unorthodox for his time.[159]

Leonardo's fame within his own lifetime was such that the King of France carried him away like a trophy, and was claimed to have supported him in his old age and held him in his arms as he died. Interest in Leonardo and his work has never diminished. Crowds still queue to see his best-known artworks, T-shirts still bear his most famous drawing, and writers continue to hail him as a genius while speculating about his private life, as well as about what one so intelligent actually believed in.[37]

The continued admiration that Leonardo commanded from painters, critics and historians is reflected in many other written tributes. Baldassare Castiglione, author of Il Cortegiano (The Courtier), wrote in 1528: "...Another of the greatest painters in this world looks down on this art in which he is unequalled..."[160] while the biographer known as "Anonimo Gaddiano" wrote, c. 1540: "His genius was so rare and universal that it can be said that nature worked a miracle on his behalf..."[161] Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists (1568), opens his chapter on Leonardo:[‡ 11]

In the normal course of events many men and women are born with remarkable talents; but occasionally, in a way that transcends nature, a single person is marvellously endowed by Heaven with beauty, grace and talent in such abundance that he leaves other men far behind, all his actions seem inspired and indeed everything he does clearly comes from God rather than from human skill. Everyone acknowledged that this was true of Leonardo da Vinci, an artist of outstanding physical beauty, who displayed infinite grace in everything that he did and who cultivated his genius so brilliantly that all problems he studied he solved with ease.

The 19th century brought a particular admiration for Leonardo's genius, causing Henry Fuseli to write in 1801: "Such was the dawn of modern art, when Leonardo da Vinci broke forth with a splendour that distanced former excellence: made up of all the elements that constitute the essence of genius..."[162] This is echoed by A. E. Rio who wrote in 1861: "He towered above all other artists through the strength and the nobility of his talents."[163]

By the 19th century, the scope of Leonardo's notebooks was known, as well as his paintings. Hippolyte Taine wrote in 1866: "There may not be in the world an example of another genius so universal, so incapable of fulfilment, so full of yearning for the infinite, so naturally refined, so far ahead of his own century and the following centuries."[164]

Art historian Bernard Berenson wrote in 1896:

Leonardo is the one artist of whom it may be said with perfect literalness: Nothing that he touched but turned into a thing of eternal beauty. Whether it be the cross section of a skull, the structure of a weed, or a study of muscles, he, with his feeling for line and for light and shade, forever transmuted it into life-communicating values.[165]

The interest in Leonardo's genius has continued unabated; experts study and translate his writings, analyse his paintings using scientific techniques, argue over attributions and search for works which have been recorded but never found.[166] Liana Bortolon, writing in 1967, said:

Because of the multiplicity of interests that spurred him to pursue every field of knowledge...Leonardo can be considered, quite rightly, to have been the universal genius par excellence, and with all the disquieting overtones inherent in that term. Man is as uncomfortable today, faced with a genius, as he was in the 16th century. Five centuries have passed, yet we still view Leonardo with awe.[36]

The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana is a special collection at the University of California, Los Angeles.[167]

Twenty-first-century author Walter Isaacson based much of his biography of Leonardo[104] on thousands of notebook entries, studying the personal notes, sketches, budget notations, and musings of the man whom he considers the greatest of innovators. Isaacson was surprised to discover a "fun, joyous" side of Leonardo in addition to his limitless curiosity and creative genius.[168]

On the 500th anniversary of Leonardo's death, the Louvre in Paris arranged for the largest ever single exhibit of his work, called Leonardo, between November 2019 and February 2020. The exhibit includes over 100 paintings, drawings and notebooks. Eleven of the paintings that Leonardo completed in his lifetime were included. Five of these are owned by the Louvre, but the Mona Lisa was not included because it is in such great demand among general visitors to the Louvre; it remains on display in its gallery. Vitruvian Man, however, is on display following a legal battle with its owner, the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice. Salvator Mundi[ab] was also not included because its Saudi owner did not agree to lease the work.[171][172]

The Mona Lisa, considered Leonardo's magnum opus, is often regarded as the most famous portrait ever made.[3][173] The Last Supper is the most reproduced religious painting of all time,[157] and Leonardo's Vitruvian Man drawing is also considered a cultural icon.[174]

More than a decade of analysis of Leonardo's genetic genealogy, conducted by Alessandro Vezzosi and Agnese Sabato, came to a conclusion in mid-2021. It was determined that the artist has 14 living male relatives. The work could also help determine the authenticity of remains thought to belong to Leonardo.[175]

Location of remains

While Leonardo was certainly buried in the collegiate church of Saint Florentin at the Château d'Amboise in 12 August 1519, the current location of his remains is unclear.[176][177] Much of Château d'Amboise was damaged during the French Revolution, leading to the church's demolition in 1802.[176] Some of the graves were destroyed in the process, scattering the bones interred there and thereby leaving the whereabouts of Leonardo's remains subject to dispute; a gardener may have even buried some in the corner of the courtyard.[176]

In 1863, fine-arts inspector general Arsène Houssaye received an imperial commission to excavate the site and discovered a partially complete skeleton with a bronze ring on one finger, white hair, and stone fragments bearing the inscriptions "EO", "AR", "DUS", and "VINC" – interpreted as forming "Leonardus Vinci".[93][176][178] The skull's eight teeth correspond to someone of approximately the appropriate age, and a silver shield found near the bones depicts a beardless Francis I, corresponding to the king's appearance during Leonardo's time in France.[178]

Houssaye postulated that the unusually large skull was an indicator of Leonardo's intelligence; author Charles Nicholl describes this as a "dubious phrenological deduction".[176] At the same time, Houssaye noted some issues with his observations, including that the feet were turned toward the high altar, a practice generally reserved for laymen, and that the skeleton of 1.73 metres (5.7 ft) seemed too short.[178][failed verification – see discussion] Art historian Mary Margaret Heaton wrote in 1874 that the height would be appropriate for Leonardo.[179] The skull was allegedly presented to Napoleon III before being returned to the Château d'Amboise, where they were re-interred in the chapel of Saint Hubert in 1874.[178][180] A plaque above the tomb states that its contents are only presumed to be those of Leonardo.[177]

It has since been theorised that the folding of the skeleton's right arm over the head may correspond to the paralysis of Leonardo's right hand.[82][88][178] In 2016, it was announced that DNA tests would be conducted to determine whether the attribution is correct.[180] The DNA of the remains will be compared to that of samples collected from Leonardo's work and his half-brother Domenico's descendants;[180] it may also be sequenced.[181]

In 2019, documents were published revealing that Houssaye had kept the ring and a lock of hair. In 1925, his great-grandson sold these to an American collector. Sixty years later, another American acquired them, leading to their being displayed at the Leonardo Museum in Vinci beginning on 2 May 2019, the 500th anniversary of the artist's death.[93][182]

Notes

General

- ^ a b See Nicholl (2005, pp. 17–20) and Bambach (2019, p. 24) for further information on the dispute and uncertainty surrounding Leonardo's exact birthplace.

- ^ a b /ˌliːəˈnɑːrdoʊ də ˈvɪntʃi, ˌliːoʊˈ-, ˌleɪoʊˈ-/ LEE-ə-NAR-doh də VIN-chee, LEE-oh-, LAY-oh-; Italian: [leoˈnardo di ˌsɛr ˈpjɛːro da (v)ˈvintʃi] .

- ^ The inclusion of the title ser (shortening of Italian messer or messere, title of courtesy prefixed to the first name) indicates that Leonardo's father was a gentleman (a low-ranking nobleman).

- ^ The diary of his paternal grandfather Ser Antonio relays a precise account: "There was born to me a grandson, son of Ser Piero, on 15 April, a Saturday, at the third hour of the night."[13][14] Ser Antonio records Leonardo being baptised the following day by Piero di Bartolomeo at the parish of Santa Croce.[15]

- ^ It has been suggested that Caterina may have been a slave from the Middle East "or at least, from the Mediterranean" or even of Chinese descent. According to art critic Alessandro Vezzosi, head of the Leonardo Museum in Vinci, there is evidence that Piero owned a slave called Caterina.[19] The reconstruction of one of Leonardo's fingerprints shows a pattern that matches 60% of people of Middle Eastern origin, suggesting the possibility that Leonardo may have had Middle Eastern blood. The claim is refuted by Simon Cole, associate professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California at Irvine: "You can't predict one person's race from these kinds of incidences, especially if looking at only one finger". More recently, historian Martin Kemp, after digging through overlooked archives and records in Italy, found evidence that Leonardo's mother was a young local woman identified as Caterina di Meo Lippi.[20]

- ^ See Kemp & Pallanti (2017, pp. 65–66) for detailed table on Ser Piero's marriages.

- ^ He also never wrote about his father, except a passing note of his death in which he overstates his age by three years.[25] Leonardo's siblings caused him difficulty after his father's death in a dispute over their inheritance.[26]

- ^ The humanist influence of Donatello's David can be seen in Leonardo's late paintings, particularly John the Baptist.[34][33]

- ^ The "diverse arts" and technical skills of Medieval and Renaissance workshops are described in detail in the 12th-century text On Divers Arts by Theophilus Presbyter and in the early 15th-century text Il Libro Dell'arte O Trattato Della Pittui by Cennino Cennini.

- ^ That Leonardo joined the guild by this time is deduced from the record of payment made to the Compagnia di San Luca in the company's register, Libro Rosso A, 1472–1520, Accademia di Belle Arti.[14]

- ^ On the back he wrote: "I, staying with Anthony, am happy," possibly in reference to his father.

- ^ Leonardo later wrote in the margin of a journal, "The Medici made me and the Medici destroyed me."[36]

- ^ In 2005, the studio was rediscovered during the restoration of part of a building occupied for 100 years by the Department of Military Geography.[62]

- ^ Both works are lost. The entire composition of Michelangelo's painting is known from a copy by Aristotole da Sangallo, 1542.[67] Leonardo's painting is known only from preparatory sketches and several copies of the centre section, of which the best known, and probably least accurate, is by Peter Paul Rubens.[68]

- ^ Pope Leo X is quoted as saying, "This man will never accomplish anything! He thinks of the end before the beginning!"[74]

- ^ There is no documentary basis for the frequently made claim that Leonardo was present at the meeting between Francis I and Leo X, which took place in Bologna from 11 to 14 December 1516.[77]

- ^ It is unknown for what occasion the mechanical lion was made, but it is believed to have greeted the King at his entry into Lyon and perhaps was used for the peace talks between the French king and Pope Leo X in Bologna. A conjectural recreation of the lion has been made and is on display in the Museum of Bologna.[80]

- ^ Identified via its similarity to Leonardo's presumed self-portrait.[83]

- ^ "... Messer Lunardo Vinci [sic] ... an old graybeard of more than 70 years ... showed His Excellency three pictures ... from whom, since he was then subject to a certain paralysis of the right hand, one could not expect any more good work."[84]

- ^ This scene is portrayed in romantic paintings by Ingres, Ménageot and other French artists, as well as Angelica Kauffman.

- ^ a b On the day of Leonardo's death, a royal edict was issued by the King at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a two-day journey from Clos Lucé. This has been taken as evidence that King Francis cannot have been present at Leonardo's deathbed, but the edict was not signed by the King.[91]

- ^ Each of the sixty paupers were to have been awarded in accord with Leonardo's will.[50]

- ^ These qualities of Leonardo's works are discussed in Hartt (1970, pp. 387–411)

- ^ The painting, which in the 18th century belonged to Angelica Kauffman, was later cut up. The two main sections were found in a junk shop and cobbler's shop and were reunited.[110] It is probable that outer parts of the composition are missing.

- ^ This work is now in the collection of the Uffizi, Drawing No. 8P.

- ^ The "Grecian profile" has a continuous straight line from forehead to nose-tip, the bridge of the nose being exceptionally high. It is a feature of many Classical Greek statues.

- ^ He also drew with his left hand, his hatch strokes "slanting down from left to right – the natural stroke of a left-handed artist".[134] He also sometimes wrote conventionally with his right hand.[135]

- ^ Salvator Mundi, a painting by Leonardo depicting Jesus holding an orb, sold for a world record US$450.3 million at a Christie's auction in New York, 15 November 2017.[169] The highest known sale price for any artwork was previously US$300 million, for Willem de Kooning's Interchange, which was sold privately in September 2015.[170] The highest price previously paid for a work of art at auction was for Pablo Picasso's Les Femmes d'Alger, which sold for US$179.4 million in May 2015 at Christie's New York.[170]

Dates of works

- ^ The Adoration of the Magi

- Kemp (2019, p. 27): c. 1481–1482

- Marani (2003, p. 338): 1481

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 56): c. 1480–1482

- Zöllner (2019, p. 222): 1481/1482

- ^ Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre version)

- Kemp (2019, p. 41): c. 1483–1493

- Marani (2003, p. 339): between 1483 and 1486

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 164): 1483–c. 1485

- Zöllner (2019, p. 223): 1483–1484/1485

- ^ Saint John the Baptist

- Kemp (2019, p. 189): c. 1507–1514

- Marani (2003, p. 340): c. 1508

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 63): c. 1500 onwards

- Zöllner (2019, p. 248): c. 1508–1516

- ^ The Annunciation

- Kemp (2019, p. 6): c. 1473–1474

- Marani (2003, p. 338): c. 1472–1475

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 15): c. 1472–1476

- Zöllner (2019, p. 216): c. 1473–1475

- ^ Saint Jerome in the Wilderness

- Kemp (2019, p. 31): c. 1481–1482

- Marani (2003, p. 338): probably c. 1480

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 139): c. 1488–1490

- Zöllner (2019, p. 221): c. 1480–1482

- ^ Lady with an Ermine

- Kemp (2019, p. 49): c. 1491

- Marani (2003, p. 339): 1489–1490

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 111): c. 1489–1490

- Zöllner (2019, p. 226): 1489/1490

- ^ The Last Supper

- Kemp (2019, p. 67): c. 1495–1497

- Marani (2003, p. 339): between 1494 and 1498

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 252): 1492–1497/1498

- Zöllner (2019, p. 230): c. 1495–1498

- ^ Mona Lisa

- Kemp (2019, p. 127): c. 1503–1515

- Marani (2003, p. 340): c. 1503–1504; 1513–1514

- Syson et al. (2011, p. 48): c. 1502 onward

- Zöllner (2019, p. 240): c. 1503–1506; 1510

References

Citations

Early

- ^ Vasari 1991, p. 287

- ^ Vasari 1991, pp. 287–289

- ^ a b c Vasari 1991, p. 293

- ^ Vasari 1991, p. 297

- ^ Vasari 1991, p. 284

- ^ Vasari 1991, p. 286

- ^ a b c Vasari 1991, p. 290

- ^ Vasari 1991, pp. 289–291

- ^ Vasari 1991, p. 294

- ^ Vasari 1965, p. 266

- ^ Vasari 1965, p. 255

Modern

- ^ "A portrait of Leonardo c. 1515–18". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ a b Zöllner 2019, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kemp 2003.

- ^ a b c d Heydenreich 2020.

- ^ Zöllner 2019, p. 250.

- ^ Kaplan, Erez (1996). "Roberto Guatelli's Controversial Replica of Leonardo da Vinci's Adding Machine". Archived from the original on 29 May 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Kaplan, E. (April 1997). "Anecdotes". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 19 (2): 62–69. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1997.586074. ISSN 1058-6180. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Capra 2007, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 7.

- ^ Kemp 2006, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown 1998, p. 5.

- ^ Nicholl 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Vezzosi 1997, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 83.

- ^ Nicholl 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Bambach 2019, pp. 16, 24.

- ^ a b Marani 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Bambach 2019, p. 16.

- ^ Hooper, John (12 April 2008). "Da Vinci's mother was a slave, Italian study claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (21 May 2017). "Tuscan archives yield up secrets of Leonardo's mystery mother". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Bambach 2019, p. 24.

- ^ Nicholl 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Kemp & Pallanti 2017, p. 65.

- ^ a b Kemp & Pallanti 2017, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Wallace 1972, p. 11.

- ^ Magnano 2007, p. 138.

- ^ Brown 1998, pp. 1, 5.

- ^ Marani 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 175.

- ^ Nicholl 2005, p. 28.

- ^ Nicholl 2005, p. 30, 506.

- ^ Nicholl 2005, p. 30. See p. 506 for the original Italian.

- ^ a b c Rosci 1977, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Hartt 1970, pp. 127–133.

- ^ Bacci, Mina (1978) [1963]. The Great Artists: Da Vinci. Translated by Tanguy, J. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bortolon 1967.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Arasse 1998.

- ^ Rosci 1977, p. 27.

- ^ Martindale 1972.

- ^ a b c d Rosci 1977, pp. 9–20.

- ^ Piero della Francesca, On Perspective for Painting (De Prospectiva Pingendi)

- ^ a b Rachum, Ilan (1979). The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 88.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 13.

- ^ a b Polidoro, Massimo (2019). "The Mind of Leonardo da Vinci, Part 1". Skeptical Inquirer. 43 (2). Center for Inquiry: 30–31.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 15.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth; Kemp, Martin (26 November 2015). Leonardo da Vinci (Newition ed.). United Kingdom: Penguin. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-14-198237-3.

- ^ a b Wasserman 1975, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Wallace 1972, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c Williamson 1974.

- ^ Kemp 2011.

- ^ Franz-Joachim Verspohl, Michelangelo Buonarroti und Leonardo Da Vinci: Republikanischer Alltag und Künstlerkonkurrenz in Florenz zwischen 1501 und 1505 (Wallstein Verlag, 2007), p. 151.

- ^ Schofield, Richard. "Amadeo, Bramante and Leonardo and the Cupola of Milan Cathedral". Achademia Leonardi Vinci. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Barbieri, Ezio; Catanese, Filippo (January 2020). "Leonardo a (e i rapporti con) Pavia: una verifica sui documenti". Annuario dell'Archivio di Stato di Milano. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Carlo Pedretti, Leonardo da Vinci: drawings of horses and other animals (Windsor Castle. Royal Library) 1984.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 79.

- ^ Moffitt, John F. (1990). "Leonardo's "Sala delle Asse" and the Primordial Origins of Architecture". Arte Lombarda (92/93 (1–2)). Vita e Pensiero – Pubblicazioni dell’Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore: 76–90. JSTOR 43132702. Archived from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Rocky, Ruggiero (6 October 2021). "Episode 142 – Leonardo da Vinci's Sala delle Asse". rockyruggiero.com. Making Art and History Come to Life, Rebuilding the Renaissance. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Segui il restauro" [Follow the restoration]. Castello Sforzesco – Sala delle Asse (in Italian). Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 85.

- ^ Owen, Richard (12 January 2005). "Found: the studio where Leonardo met Mona Lisa". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 124.

- ^ "Mona Lisa – Heidelberg discovery confirms identity". University of Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Delieuvin, Vincent (15 January 2008). "Télématin". Journal Télévisé. France 2 Télévision.

- ^ Coughlan, Robert (1966). The World of Michelangelo: 1475–1564. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 90.

- ^ Goldscheider, Ludwig (1967). Michelangelo: paintings, sculptures, architecture. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-1314-1.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b c d e Wallace 1972, p. 145.

- ^ "Achademia Leonardi Vinci". Journal of Leonardo Studies & Bibliography of Vinciana. VIII: 243–244. 1990.

- ^ a b c Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 86.

- ^ a b Wallace 1972, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e Wallace 1972, p. 150.

- ^ Ohlig, Christoph P. J., ed. (2005). Integrated Land and Water Resources Management in History. Books on Demand. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-8334-2463-2.

- ^ Gillette, Henry Sampson (2017). Leonardo da Vinci: Pathfinder of Science. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 84. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Laurenza, Domenico (2004). "Leonardo nella Roma di Leone X". Lettura Vinciana (in Italian). XLIII. Giunti.

- ^ Sammer, Jan (2009). "L'Invitation du roi". In Pedretti, Carlo (ed.). Léonard de Vinci et la France (in French). CB Edizioni. pp. 29–33.

- ^ Wallace 1972, pp. 163, 164.

- ^ "Reconstruction of Leonardo's walking lion" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 25 August 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Brown, Mark (1 May 2019). "Newly identified sketch of Leonardo da Vinci to go on display in London". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ a b Strickland, Ashley (4 May 2019). "What caused Leonardo da Vinci's hand impairment?". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b McMahon, Barbara (1 May 2005). "Da Vinci 'paralysis left Mona Lisa unfinished'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 163.

- ^ a b Lorenzi, Rossella (10 May 2016). "Did a Stroke Kill Leonardo da Vinci?". Seeker. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Saplakoglu, Yasemin (4 May 2019). "A Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci May Reveal Why He Never Finished the Mona Lisa". Live Science. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ a b Bodkin, Henry (4 May 2019). "Leonardo da Vinci never finished the Mona Lisa because he injured his arm while fainting, experts say". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ a b Charlier, Philippe; Deo, Saudamini. "A physical sign of stroke sequel on the skeleton of Leonardo da Vinci?" Archived 15 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Neurology. 4 April 2017; 88(14): 1381–1382

- ^ Ian Chilvers (2003). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-19-953294-0.

- ^ Antonina Vallentin, Leonardo da Vinci: The Tragic Pursuit of Perfection, (New York: The Viking Press, 1938), 533

- ^ White, Leonardo: The First Scientist

- ^ Kemp 2011, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Florentine editorial staff (2 May 2019). "Hair believed to have belonged to Leonardo on display in Vinci". The Florentine. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ Gasca, Nicolò & Lucertini 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Leonardo, Codex C. 15v. Institut of France. Trans. Richter.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 84.

- ^ Rossiter, Nick (4 July 2003). "Could this be the secret of her smile?". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ a b Pedretti, Carlo, ed. (2009). Leonardo da Vinci: l'Angelo incarnato & Salai = the Angel in the flesh & Salai. Foligno (Perugia): Cartei & Bianchi. p. 201. ISBN 978-88-95686-11-0. OCLC 500794484.

- ^ MacCurdy, Edward, The Mind of Leonardo da Vinci (1928) in Leonardo da Vinci's Ethical Vegetarianism Archived 27 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bambach 2003.

- ^ Cartwright Ady, Julia. Beatrice d'Este, Duchess of Milan, 1475–1497. Publisher: J.M. Dent, 1899; Cartwright Ady, Julia. Isabella D'Este, Marchioness of Mantua, 1474–1539. Publisher; J.M. Dent, 1903.

- ^ Sigmund Freud, Eine Kindheitserinnerung des Leonardo da Vinci, (1910)

- ^ Isaacson 2017, pp. 129–138.

- ^ a b Isaacson 2017.

- ^ "Leonardo, ladies' man: why can't we accept that Da Vinci was gay?". The Guardian. 26 March 2021. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships epigraph, p. 148 & N120 p. 298

- ^ Arasse 1998, pp. 11–15.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, pp. 88, 90.

- ^ Marani 2003, p. 338.

- ^ a b Wasserman 1975, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Wasserman 1975, p. 108.

- ^ "The Mysterious Virgin". National Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ^ a b "Da Vinci's Lady with an Ermine among Poland's "Treasures" – Event – Culture.pl". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Kemp, M. The Lady with an Ermine in the exhibition Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Washington-New Haven-London. p. 271.

- ^ Wasserman 1975, p. 124.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 97.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 98.

- ^ Seracini, Maurizio (2012). "The Secret Lives of Paintings" (lecture). Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Wasserman 1975, p. 144.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 103.

- ^ Wasserman 1975, p. 150.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Popham, A. E. (1946). The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci.

- ^ Ottino della Chiesa 1967, p. 102.

- ^ Hartt 1970, pp. 391–392.

- ^ a b c Wallace 1972, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Keele Kenneth D (1964). "Leonardo da Vinci's Influence on Renaissance Anatomy". Med Hist. 8 (4): 360–370. doi:10.1017/s0025727300029835. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 1033412. PMID 14230140.

- ^ Bean, Jacob; Stampfle, Felice (1965). Drawings from New York Collections I: The Italian Renaissance. Greenwich, CT: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 81–82.

- ^ Major, Richard Henry (1866). Archaeologia: Or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity, Volume 40, Part 1. London: The Society. pp. 15–16. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Calder, Ritchie (1970). Leonardo & the Age of the Eye. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-671-20713-7.