The laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae) is a bird in the kingfisher subfamily Halcyoninae. It is a large robust kingfisher with a whitish head and a brown eye-stripe.[2] The upperparts are mostly dark brown but there is a mottled light-blue patch on the wing coverts.[3][2] The underparts are cream-white and the tail is barred with rufous and black.[2] The plumage of the male and female birds is similar. The territorial call is a distinctive laugh that is often delivered by several birds at the same time, and is widely used as a stock sound effect in situations that involve a jungle setting.[4]

| Laughing kookaburra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Recorded in southwestern Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Coraciiformes |

| Family: | Alcedinidae |

| Subfamily: | Halcyoninae |

| Genus: | Dacelo |

| Species: | D. novaeguineae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dacelo novaeguineae (Hermann, 1783)

| |

| |

| Distribution within Australia Dark green: native Light green: introduced | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The laughing kookaburra is native to eastern mainland Australia, but has also been introduced to parts of New Zealand, Tasmania, and Western Australia.[5] It occupies dry eucalypt forest, woodland, city parks and gardens.[5] This species is sedentary and occupies the same territory throughout the year. It is monogamous, retaining the same partner for life. A breeding pair can be accompanied by up to five fully grown non-breeding offspring from previous years that help the parents defend their territory and raise their young.[5] The laughing kookaburra generally breeds in unlined tree holes or in excavated holes in arboreal termite nests.[5] The usual clutch is three white eggs. The parents and the helpers incubate the eggs and feed the chicks. The youngest of the three nestlings or chicks is often killed by the older siblings. When the chicks fledge they continue to be fed by the group for six to ten weeks until they are able to forage independently.[6]

A predator of a wide variety of small animals, the laughing kookaburra typically waits perched on a branch until it sees an animal on the ground and then flies down and pounces on its prey.[3] Its diet includes lizards, insects, worms, snakes, mice and it is known to take goldfish out of garden ponds.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classed the laughing kookaburra as a species of least concern as it has a large range and population, with no widespread threats.[1]

Taxonomy

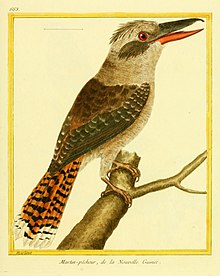

editThe laughing kookaburra was first described and illustrated (in black and white) by the French naturalist and explorer Pierre Sonnerat in his Voyage à la nouvelle Guinée, which was published in 1776.[7][8] He claimed to have seen the bird in New Guinea. In fact Sonnerat never visited New Guinea and the laughing kookaburra does not occur there. He probably obtained a preserved specimen from one of the naturalists who accompanied Captain James Cook to the east coast of Australia.[9] Edme-Louis Daubenton and François-Nicolas Martinet included a coloured plate of the laughing kookaburra based on Sonnerat's specimen in their Planches enluminées d'histoire naturelle. The plate has the legend in French "Martin-pecheur, de la Nouvelle Guinée" (Kingfisher from New Guinea).[10]

In 1783, the French naturalist Johann Hermann provided a formal description of the species based on the coloured plate by Daubenton and Martinet. He gave it the scientific name Alcedo novæ Guineæ.[11][12] The current genus Dacelo was introduced in 1815 by the English zoologist William Elford Leach,[13][14] and is an anagram of Alcedo, the Latin word for a kingfisher. The specific epithet novaeguineae combines the Latin novus for new with Guinea,[15] based on the erroneous belief that the specimen had originated from New Guinea.[8] For many years it was believed that the earliest description was by the Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert and his scientific name Dacelo gigas was used in the scientific literature,[16] but in 1926 the Australian ornithologist Gregory Mathews showed that a description by Hermann had been published earlier in the same year, 1783, and thus had precedence.[8][17] The inaccurate impression of geographic distribution given by the name in current usage had not by 1977 been considered an important enough matter to force a change in favor of D. gigas.[8]

In the 19th century this species was commonly called the "laughing jackass", a name first recorded (as Laughing Jack-Ass) in An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales by David Collins which was published in 1798.[18][19] In 1858 the ornithologist John Gould used "great brown kingfisher", a name that had been coined by John Latham in 1782.[20][21] Another popular name was "laughing kingfisher".[19] The names in several Australian indigenous languages were listed by European authors including Go-gan-ne-gine by Collins in 1798,[18] Cuck'anda by René Lesson in 1828[22] and Gogera or Gogobera by George Bennett in 1834.[23] In the early years of the 20th century "kookaburra" was included as an alternative name in ornithological publications,[24][25] but it was not until 1926 in the second edition of the Official Checklist of Birds of Australia that the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union officially adopted the name "laughing kookaburra".[19] The name comes from Wiradjuri, an endangered Aboriginal language.[19]

The genus Dacelo contains four kookaburra species of which the rufous-bellied kookaburra and the spangled kookaburra are restricted to New Guinea and islands in the Torres Straits. The blue-winged kookaburra and the laughing kookaburra are both widespread in Australia.[26]

Two subspecies are recognised:[27]

- D. n. novaeguineae (Hermann, 1783) – the nominate subspecies, east Australia, Tasmania and introduced into southwest Australia

- D. n. minor Robinson, 1900 – Cape York Peninsula south to Cooktown[28][6]

Description

editThe laughing kookaburra is the largest species of kingfisher, outsizing even the giant kingfisher in body mass.[6][29] It is a stout, stocky bird 41–47 cm (16–19 in) in length, with a large head, prominent brown eyes, and a long and robust bill.[2] The sexes are very similar, although the female is usually larger and has less blue to the rump than the male. The male weighs 196–450 g (6.9–15.9 oz), mean 307 g (10.8 oz) and the female 190–465 g (6.7–16.4 oz), mean 352 g (12.4 oz).[30] They have a white or cream-coloured body and head with a dark brown stripe across each eye and more faintly over the top of the head. The wings and back are brown with sky blue spots on the shoulders. The tail is rusty reddish-orange with dark brown bars and white tips on the feathers. The heavy bill is black on top and bone-coloured on the bottom. The subspecies D. n. minor has a similar plumage to the nominate but is smaller in size.[6]

The laughing kookaburra can be distinguished from the similarly sized blue-winged kookaburra by its dark eye, dark eye-stripe, shorter bill and the smaller and duller blue areas on the wing and rump.[6] Male blue-winged kookaburras also differ in having a barred blue and black tail.[6]

Call

editThe name "laughing kookaburra" refers to the bird's "laugh", which it uses to establish territory among family groups. It can be heard at any time of day, but most frequently at dawn and dusk.[6]

This species possesses a tracheo-bronchial syrinx, which creates two sources of vibrations so it can produce two frequencies at the same time with multiple harmonics.[5] The laughing kookaburras call is made through a complex sound production system, by forcing air from the lungs into the bronchial tubes.[5] While the structure for producing calls is present from an early age, the kookaburra's song is a learned behavior.[31] The breeding pair within a riot of kookaburra teach the fledglings to produce the signature laughing call after the young have left the nest.[31] The adult male will sing a short portion of the call while the offspring mimics this call, usually unsuccessfully.[31] The singing lessons tend to last two weeks before the fledgling can properly sing and take part in crepuscular choral songs.[31] Once mastered, the young can join in crepuscular chorus songs that aid in establishing territory.[31]

One bird starts with a low, hiccuping chuckle, then throws its head back in raucous laughter: often several others join in.[3][30] If a rival tribe is within earshot and replies, the whole family soon gathers to fill the bush with ringing laughter.[2] The laughing chorus has 5 variable elements: 1. "Kooa"; 2. "Cackle"; 3. "Rolling", a rapidly repeated "oo-oo-oo"; 4. Loud "Ha-ha"; followed by 5. Male's call of "Go-go" or female's call of "Gurgle".[30] Hearing kookaburras in full voice is one of the more extraordinary experiences of the Australian bush, something even locals cannot ignore; some visitors, unless forewarned, may find their calls startling.

Those calls are produced to attract/guard mates, establish and maintain the social hierarchy, and declare and defend a territory, as their calls are more often correlated with aggressiveness.[32] Calls are utilized as neighbour/kin recognition to exhibit that groups are still inhabiting a territory.[31] These calls also demonstrate to receivers that highly coordinated groups are of better quality and health.[33] Acoustic communication between laughing kookaburras increases 2–3 months before the breeding season, September to January, because male aggression also increases.[5]

The duetting call requires higher levels of cooperation within the group.[5] The coordination of calls amongst kookaburras has been hypothesized to strengthen the main long-term pair bond and may have evolved as a mechanism to solidify the group's bonds since it is energetically costly to learn a new song.[33] Neighbouring groups exhibit degrees of cooperation as well since chorus songs between neighbours are delivered without any overlap, alternating between groups.[31]

Other forms of acoustic communication

editSquawking is another common form of acoustic communication in D. novaeguineae that is used in a slew of different contexts.[30] Laughing kookaburras have been noted to squawk when nesting, exhibiting submissive behavior, and when fledglings are waiting to be fed.[30] Laughing kookaburras have a greater repertoire of calls than other kookaburra species like the Blue-winged kookaburra (Dacelo leachii) that produces two simple types of calls: “barks” and “hiccups”.[34] This large range of calls is highlighted through cadencing, intonation, and frequency modulations that allow more detailed information to be conveyed.[35]

Distribution and habitat

editThe laughing kookaburra is native to eastern Australia and has a range that extends from the Cape York Peninsula in the north to Cape Otway in the south. It is present on both the eastern and the western sides of the Great Dividing Range. In the south the range extends westwards from Victoria to the Yorke Peninsula and the Flinders Ranges in South Australia.[36]

It has been introduced into many other areas probably because of its reputation for killing snakes. In December 1891, the Western Australian parliament included 'Laughing Jackass' in the schedule of strictly preserved Australian native birds in the Game Bill, moved by Horace Sholl, member for North District. He described it as native of the North West.[37] His nomination is, therefore, certainly a reference to the blue-winged kookaburra (Dacelo leachii), not the laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae). The Game Act, 1892 (Western Australia), "An Act to provide for the preservation of imported birds and animals, and of native game," provided that proclaimed Australian native birds and animals listed in the First Schedule of the Act could be declared protected from taking. Laughing Jackass was one of 23 Australian native bird species named in the schedule.

Laughing kookaburras from Eastern States were released to the South West as early as 1883,[38] with birds being noted between Perth and Fremantle, as well as up in Mullewa around 1896.[39] The Acclimatization Society (or Animal and Bird Acclimatization committee of WA) imported and released hundreds of birds between 1897 and 1912.[40] Mainly via Ernest Le Souef who was Secretary of the Acclimatization Society and Director of Perth Zoological Gardens, an enthusiastic supporter of the Kookaburra who admitted to releasing hundreds from the Zoo, including 50 in 1900 at the Royal request of the visiting Duke of York.

By 1912 breeding populations had been established in a number of areas. The present range in Western Australia is southwest of a line joining Geraldton on the west coast and Hopetoun on the south coast.[5] In Tasmania the laughing kookaburra was introduced at several locations beginning in 1906. It now mainly occurs northeast of a line joining Huonville, Lake Rowallan, Waratah and Marrawah.[5] It was introduced on Flinders Island in around 1940, where it is now widespread, and on Kangaroo Island in 1926.[5]

In the 1860s, during his second term as governor of New Zealand, George Grey arranged for the release of laughing kookaburras on Kawau Island. The island lies in the Hauraki Gulf, about 40 km (25 mi) north of Auckland on the North Island of New Zealand. It was thought that the introduction had been unsuccessful but in 1916 some birds were discovered on the adjacent mainland.[36][41] It now breeds in a small region on the western side of the Hauraki Gulf between Leigh and Kumeū.[36]

The usual habitat is open sclerophyll forest and woodland. It is more common where the understory is open and sparse or where the ground is covered with grass. Tree-holes are needed for nesting. It also occurs near wetlands and in partly cleared areas or farmland with trees along roads and fences. In urban areas it is found in parks and gardens.[42] The range of the laughing kookaburra overlaps with that of the blue-winged kookaburra in an area of eastern Queensland that extends from the Cape York Peninsula south to near Brisbane. Around Cooktown the laughing kookaburra tends to favour areas near water while the blue-winged kookaburra keeps to drier habitats.[6]

A single individual Laughing Kookaburra, has been living wild, in Suffolk, in the UK, since at least 2015, being most recently sighted in 2024.[43] Additional sightings of laughing kookaburras have been recorded in Scotland,[44] suggesting that individuals of the species may be being intentionally or accidentally released.

Behaviour

editKookaburras occupy woodland territories (including forests) in loose family groups, and their laughter serves the same purpose as a great many other bird calls—to mark territorial borders. Most species of kookaburras tend to live in family units, with offspring helping the parents hunt and care for the next generation of offspring.

Breeding

editDuring mating season, the laughing kookaburra reputedly indulges in behaviour similar to that of a wattlebird. The female adopts a begging posture and vocalises like a young bird. The male then offers her his current catch accompanied with an "oo oo oo" sound. However, some observers maintain that the opposite happens – the female approaches the male with her current catch and offers it to him. Nest-building may start in August with a peak of egg-laying from September to November.[5] If the first clutch fails, they will continue breeding into the summer months.[5]

The female generally lays a clutch of three semi-glossy, white, rounded eggs, measuring 36 mm × 45 mm (1.4 in × 1.8 in), at about two-day intervals.[3] Both parents and auxiliaries incubate the eggs for 24–26 days.[5] Hatchlings are altricial and nidicolous, fledging by day 32–40.[5] If the food supply is not adequate, the third egg will be smaller and the third chick will also be smaller and at a disadvantage relative to its larger siblings. Chicks have a hook on the upper mandible, which disappears by the time of fledging. If the food supply to the chicks is not adequate, the chicks will quarrel, with the hook being used as a weapon. The smallest chick may even be killed by its larger siblings.[5] If food is plentiful, the parent birds spend more time brooding the chicks, so the chicks are not able to fight.

Feeding

editKookaburras hunt much as other kingfishers (or indeed Australasian robins) do, by perching on a convenient branch or wire and waiting patiently for prey to pass by. Common prey include mice and similar-sized small mammals, a large variety of invertebrates (such as insects, earthworms and snails), yabbies, small fish, lizards, frogs, small birds and nestlings, and most famously, snakes.[5][30] Small prey are preferred, but kookaburras sometimes take large creatures, including venomous snakes, much longer than their bodies.[5] When feeding their young, adult laughing kookaburras will make “Chuck calls”, which are deep, guttural calls that differ significantly from their daily chorus songs.[30]

Visual displays

editTo further enhance territorial behavior, kookaburras will partake in two types of aerial displays: trapeze and circular flights.[45] Trapeze flights are aptly named after the swooping motion that neighbouring kookaburras will make towards one another in midair when defending territory.[45] During trapeze flights, an individual from each riot will perch on branches bordering the others' territory and fly back and forth between trees within their established home range and trees bordering neighbouring kookaburras territory.[45] These displays have been observed to last up to a half an hour and are usually accompanied by calls from the sender and members of that individual's riot.[45] Circle flights are initiated when an individual circumnavigates a neighbouring territory by flying over the area and then quickly invading neighbouring territory.[45] Once inside the neighbouring territory, the individual will fly in circles around the other kookaburras inhabiting the area, which results in a typical laughing call or squawking depending on whether the neighbours' dominance status.[45] Flight displays are useful for communicating over long distances, but other forms of visual signals can be effective for short-range communication.

Close range visual signals can be used to convey aggression or indicate incoming threats to the flock.[45] Aggressive posturing is used as a warning before attacking, a signal that is commonly received by foreign kookaburras encroaching on another groups' territory.[46] Laughing kookaburras will splay out their wings and propel their head forward while shaking their tail feathers to exhibit dominance and ward off intruders.[46] The aggressive posturing is followed up by chasing off the unwanted individual before attacking.[5] Visual displays are also used to communicate vigilance and the presence of threats via alert postures.[5] D. novaeguineae will open its beak, ruffle up the feathers surrounding its cap, and angle their heads towards the direction of the threat.[5] Depending on the urgency of the threat, alarm postures may be followed by loud laugh-like calls to warn other members of the flock.[5]

Relationship with humans

editLaughing kookaburras are a common sight in suburban gardens and urban settings, even in built-up areas, and are so tame that they will often eat out of a person's hands, and allow them to rub their bellies. It is not uncommon for kookaburras to snatch food out of people's hands without warning, by swooping in from a distance. People often feed them pieces of raw meat. Laughing kookaburras are often kept in zoos.

The kookaburra is also the subject of a popular Australian children's song, the "Kookaburra" which was written by Marion Sinclair in 1934.[47]

Recordings of this bird have been edited into Hollywood movies for decades, usually in jungle settings, beginning with the Tarzan series in the 1930s, and more recently in the film The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997).[4]

Conservation status

editThe population density of the laughing kookaburra in Australia varies between 0.04 and 0.8 birds/ha depending on the habitat. Assuming an average of 0.3 birds/ha the total population may be as large as 65 million individuals.[6] However, this may represent a severe over-estimate since the population of the laughing kookaburra seems to be undergoing a marked decline with Birdata showing a 50% drop in sightings from 2000 to 2019, and a drop in the reporting rate from 25% to 15% over the same period.[48] The population in New Zealand is relatively small and is probably less than 500 individuals.[49] Given the extended range and the large stable population, the species is evaluated as of "least concern" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2016). "Dacelo novaeguineae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22683189A92977835. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22683189A92977835.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Pizzey, Graham and Doyle, Roy. (1980) A Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Collins Publishers, Sydney. ISBN 073222436-5

- ^ a b c d Morcombe, Michael (2012) Field Guide to Australian Birds. Pascal Press, Glebe, NSW. Revised edition. ISBN 978174021417-9

- ^ a b Kaercher, Melissa (30 May 2013). "The Sound and the Foley". Tin Lizard Productions.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Higgins, Peter J., ed. (1999). "Dacelo novaeguineae Laughing Kookaburra" (PDF). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 4: Parrots to dollarbird. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 1121–1138. ISBN 978-0-19-553071-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fry, C. H.; Fry, Kathie; Harris, Alan (1999). Kingfishers, Bee-eaters and Rollers. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 133–136. ISBN 978-0-7136-5206-2.

- ^ Sonnerat, Pierre (1776). Voyage à la Nouvelle Guinée (in French). Chez Ruault. p. 170, Plate 106.

- ^ a b c d Mees, G.F. (1977). "The scientific name of the Laughing Kookaburra: Dacelo gigas (Boddaert) v. Dacelo novaeguineae (Hermann)". Emu. 77 (1): 35–36. doi:10.1071/mu9770035.

- ^ Lysaght, A. (1956). "Why did Sonnerat record the kookaburra, Dacelo gigas (Boddaert) from New Guinea?". Emu. 56 (3): 224–225. doi:10.1071/MU956224.

- ^ Daubenton, Edme-Louis; Martinet, François-Nicolas (1765–1783). Planches enluminées d'histoire naturelle. Vol. 7. Paris. Plate 663.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1945). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 5. Vol. 5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 190.

- ^ Hermann, Johann (1783). Tabula affinitatum animalium olim academico specimine edita : nunc uberiore commentario illustrata cum annotationibus ad historiam naturalem animalium augendam facientibus (in Latin). Argentorati: Impensis Joh. Georgii Treuttel. p. 192 Note.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1945). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 5. Vol. 5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 189.

- ^ Leach, William Elford (1815). The Zoological Miscellany; being descriptions of new, or interesting Animals. Vol. 2. London: B. McMillan for E. Nodder & Son. p. 125.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 130, 275. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Boddaert, Pieter (1783). Table des planches enluminéez d'histoire naturelle de M. D'Aubenton (in French). Utrecht. p. 40.

- ^ Mathews, Gregory M. (1926). "An important date". Emu. 26: 148. doi:10.1071/mu926148.

- ^ a b Collins, David (1798). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales. London: T. Cadell Jr and W. Davies. Appendix 12 Language.

- ^ a b c d Gray, Jeannie; Fraser, Ian (2013). Australian Bird Names: A Complete Guide. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO. pp. 156–158. ISBN 978-0-64310469-3.

- ^ Gould, John (1848). The Birds of Australia. Vol. 2. London: Self-published. Plate 18.

- ^ Latham, John (1782). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 1. London: Printed for Benj. White. p. 609.

- ^ Lesson, René Primeverre (1828). Manuel d'ornithologie, ou description des genres et des principales espèces d'oiseaux (in French). Paris: Roret. p. 93.

- ^ Bennett, George (1834). Wandering in New South Wales, Batavia, Pedir Coast, Singapore, and China: being the journal of a naturalist in those countries during 1832, 1833, and 1834. Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley. p. 222.

- ^ Lucas, A.H.S.; Le Souef, W.H. Dunley (1911). The Birds of Australia. London: Whitcombe and Tombs. pp. 236–237.

- ^ Leach, John Albert (1912). An Australian bird book: a pocket book for field use (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Whitcombe & Tombs. p. 105.

- ^ Woodall, P.F. (2020). "Kingfishers (Alcedinidae)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. doi:10.2173/bow.alcedi1.01. Retrieved 2 February 2017.(subscription required)

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2016). "Rollers, ground rollers & kingfishers". World Bird List Version 6.3. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Robinson, Herbert Christopher (1900). "Contributions to the zoology of north Queensland". Bulletin of the Liverpool Museums. 2 (3&4): 116.

- ^ Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Woodall, P. F. (2020). "Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae), version 1.0." In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.laukoo1.01

- ^ a b c d e f g Baker, Myron C. (January 2004). "The Chorus Song of Cooperatively Breeding Laughing Kookaburras (Coraciiformes, Halcyonidae: Dacelo novaeguineae): Characterization and Comparison Among Groups". Ethology. 110 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0310.2003.00941.x.

- ^ Reyer, Heinz-Ulrich; Schmidl, Dieter (September 1988). "Helpers Have Little to Laugh About: Group Structure and Vocalisation in the Laughing Kookaburra Dacelo novaeguineae". Emu – Austral Ornithology. 88 (3): 150–160. doi:10.1071/mu9880150. ISSN 0158-4197.

- ^ a b Hall, Michelle L. (1 March 2004). "A review of hypotheses for the functions of avian duetting". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 55 (5): 415–430. doi:10.1007/s00265-003-0741-x. ISSN 0340-5443. S2CID 33751268.

- ^ Legge, Sarah, ed. (2004). Kookaburra: King of the Bush. Clayton South, VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. doi:10.1071/9780643091375. ISBN 978-0-643-09137-5.

- ^ Smith, W. John (31 December 2020), Kroodsma, Donald E; Miller, Edward H (eds.), "21. Using Interactive Playback to Study How Songs and Singing Contribute to Communication about Behavior", Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 377–397, doi:10.7591/9781501736957-030, ISBN 978-1-5017-3695-7, S2CID 225018688, retrieved 3 January 2021

- ^ a b c Higgins 1999, pp. 1124–1125.

- ^ The Daily News, Perth, 22 December 1891, page 3, Legislative Assembly

- ^ Sellick, Douglas. First impressions : Albany 1791-1901 :travellers' tales. pp. 151–2. ISBN 0730983668.

- ^ Jenkins, C.F .H. (1959). "Introduced Birds in Western Australia". Emu. 59: 201–207.

- ^ Long, J. L. (1974). Introduced birds and mammals in Western Australia. Agriculture Protection Board of Western Australia. p. 3. ISBN 0-7244-5758-5. OCLC 27566719.

- ^ Thomson, G.M. (1922). The Naturalisation of Animals and Plants in New Zealand. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 137–138.

- ^ Higgins 1999, p. 1123.

- ^ "Kookaburra spotted living in Suffolk countryside". BBC News. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "Kookaburras spotted in wilds of Scotland by excited adventurer: 'They're wicked'". Yahoo News. 12 April 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g ICTN; Higgins, P. J.; Davies, S. J. J. F. (1997). "Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 3: Snipe to Pigeons". Colonial Waterbirds. 20 (3): 631. doi:10.2307/1521625. ISSN 0738-6028. JSTOR 1521625.

- ^ a b Morton, S. R.; Parry, G. D. (July 1974). "The Auxiliary Social System in Kookaburras: A Reappraisal of Its Adaptive Significance". Emu – Austral Ornithology. 74 (3): 196–198. doi:10.1071/mu974195b. ISSN 0158-4197.

- ^ Howell, P. A. (2012). "Sinclair, Marion (1896–1988)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ BirdLife Australia (2020). "Explore Birdata map: Laughing kookaburra". Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ Michaux, B. (2013). Miskelly, C.M. (ed.). "Laughing kookaburra". New Zealand Birds Online. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

Further reading

edit- Legge, Sarah (2004). Kookaburra: King of the Bush. Collingwood Vic, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09063-7.

- Parry, Veronica A. (1970). Kookaburras. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 978-0-7018-0290-5.

External links

edit- Xeno-canto: audio recordings of the laughing kookaburra

- Photos, audio and video of laughing kookaburra from Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Macaulay Library

- Recordings of laughing kookaburra from Graeme Chapman's sound library